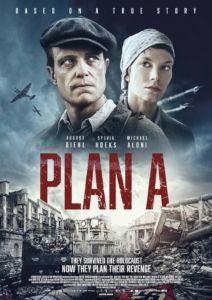

During the summer of 1945, when Germany’s cities were piles of smoldering rubble and the German people lived like rats in their cellars, the German Jews who had run away during the 1930s swarmed back into Germany lusting for revenge. Plan A is not only based on “a true story,” “this film from Israeli brothers Doron and Yoav Paz dramatizes an astonishing piece of Holocaust history: a deadly plot by a small group of Jewish survivors to poison the water supply in Nuremberg. ‘An eye for an eye. Six millions for six millions.’”

. . . If you look up Jews poisoning wells, you will learn that this is a classic anti-Semitic “canard.” Why then would two Jews make a movie about “the true story” of Jews poisoning the water works in Germany? Is it because they feel the need to justify their actions? More understandable is the German funding of this film. The folks at the Bavarian ministry of culture probably had a good laugh when the Israelis left the room because, in a classic expression of German passive aggressive behavior, they were funding a film that made Jews look like monsters . . .

Like the plot to poison the water supply which never got carried out, Plan A has yet to make it into theaters, even though it was scheduled for release in August 2021. Could it be that some big Jewish distributor took the brothers Paz aside and told them Jew to Jew that poisoning helpless Germans doesn’t make Jews look good, even if it’s payback for the Holocaust?

— E. Michael Jones, The Holocaust Narrative (2023), pp. 105-107

While I wish I shared Dr. Jones’ optimism concerning the Bavarian Ministry of Culture, I do have good news: Plan A has long been released and is available, depending on your country, for streaming or on DVD and Blu-ray.

Its English Wikipedia page is sparse, in contrast to the quite extensive German one. Am I the only one who finds the information “Not to be confused with Plan B (2021 film)“ hilarious, given the context? Because “Plan B” actually succeeded — to a point. We’ll get to it later on.

Let’s take a look at what the German Wikipedia says (my translation). I’ll interrupt frequently to add my thoughts.

The film shows the activities of the Nakam, that wanted to kill millions of Germans in the post-war period in revenge for the Holocaust and encountered the Jewish Brigade in the process. The premiere in Israel took place in September 2021 at the Haifa Film Festival. The film was released in German cinemas on December 9, 2021 and has been available as a Sky Original on the pay TV channel since June 10, 2022. It was released on DVD on November 29, 2022.

The synopsis follows. I’ll just quote the first few paragraphs and add to them, as there are several points I’d like to make regarding this text:

Max, a Jew, [played by German actor August Diehl] has survived the Holocaust and returns to his house after the war to look for his wife Ruth and son Benjamin. He is beaten and threatened by the Nazi who now lives there and who has betrayed him and his family.

What are the odds? Honestly, I doubt any “Nazi” would have dared to beat up a Jew at that point. All Max had to do was to complain to the authorities, and the Nazi would be thrown out on his ear. Requisition of living space by the Allies was a real thing back then.

That being said, the scene actually develops a bit differently. It starts with the wife of said “Nazi” in her kitchen, being alerted by her child that a stranger is standing outside. She clears the steam from the windowpane and sees some tramp just standing there and staring at the house, so she calls her husband.

What really dominates the stage is the huge cross hanging above the kitchen door. So these folks are good Christian people, right? Not so much, as we are shown immediately, when Nazi husband talks of pesky beggars. But it turns out that these Christians are not only hypocrites; they actually recognize the guy outside. So naturally, Nazi husband gets his gun.

Yes, every anti-Christian, anti-German stereotype has been established before we even meet Max. It is fitting, then, that after Nazi husband has knocked Max down, he says something as clichéd as “Just because we lost the war doesn’t mean we can’t kill Jews anymore.” It’s almost a relief to move on into Jew-only territory after that.

In the ruins of the local synagogue, where he married his wife Ruth at the time, he meets old Avram.

Avram is one of the few characters I actually liked. He is a crazy old Jew who carries around a bundle that must not under any circumstances be opened, as it contains a great evil. I don’t know if there is an equivalence in Jewish mythology, but this is clearly a reference to Pandora’s box and will play a role later on.

Max and Avram — who, incidentally, wears a striped suit; this is obviously meant to remind us of a prison uniform — set out to find a refugee camp Avram has heard of where Jews are gathering for their departure to Palestine, or “Palaestina” as they call it throughout the film. This is the original Latin name for the region that is still the German and, apparently, the Ivrit (modern Hebrew) name for it. (August Diehl also pronounces “Ruth” correctly, by the way, which is the same in German and Hebrew: “Rut”.)

You can buy Savitri Devi’s Defiance here.

Avram has a number of lines that make clear his conviction that Jews should “get out of this damn country” whose “soil is cursed, soaked in our blood,” and initially Max is content to go along, as his best chance of finding his family seems, for some reason, to be that camp.

When they come across a British army camp in the woods, Avram decides to steal some food. Of course they get caught by members of the Jewish Brigade who magically recognize them as co-ethnics right away. The Brigade is nominally under the command of a British officer, and this leads to an interesting exchange while the group escorts Max and Avram to the refugee camp. “Once [the British] are asleep we get to do whatever we want right beneath their noses,” boast the Jewish soldiers. Max is about to learn what that entails.

Michael,[1] the Brigade’s leader who is plagued by his conscience (“We should have helped you. We did nothing.”), takes Max along to an “interrogation” to give him peace or something. They need names of SS personnel from someone who is apparently a former German official. He refuses to talk and is about to be strangled by the Brigade when Max steps in and tries the soft approach by having Michael ask the man about his children — giving him hope, as he puts it. For some reason the guy is suddenly very helpful, gives out all the names and addresses, and gets strangled as a result anyway. The scene is extremely disturbing and made me think of Dr. Jones’ chapter on Steven Spielberg’s Munich in his book The Holocaust Narrative:

Here we reach the conflict that is gnawing away at Spielberg and finds expression in the radical incoherence of his movie. Munich is a Jewish propaganda film with a bad conscience. . . .

Confronted by the post Auschwitz realization that Jews in fact do . . . bad things to other people, Spielberg tries to resolve a moral dilemma with powerful acting and clever, if sometimes sentimental, cinematography. . . . According to Spielberg’s moral theology, a good Jew feels remorse after he guns you down in cold blood, but a bad Jew doesn’t. . . .

Munich is in many ways Spielberg’s protest against the violent dialectic of Jewish racial morality, but he gets caught up in it nonetheless.[2]

This is exactly what we encounter in this and several following scenes when the Jewish Brigade, in a montage of brutality, murders a number of Germans, men and women, after holding quick mock trials. It is virtually impossible to feel sympathy for what they are doing, especially as we never learn the particulars of any case. We are just supposed to accept that these people were guilty of something.

Max abandons this plan [to emigrate] when a woman tells him about a cruel Nazi mass murder, of which Ruth and Benjamin were among the victims.

That scene — I was literally hearing Devon Stack in my head: “That’s your Holocaust survivor right there!” The woman in question tells Max how she and the others had been led to their place of execution, where they were then shot until the Nazis ran out of bullets, after which they went on to stab them and finally bury them alive — and she “somehow managed to escape”!

I’m sorry, I know this is meant to be a highly emotional and decisive scene in the film, but it was just too ridiculous. The scriptwriters never even tried to explain the “somehow” of that woman’s escape. It just is.

Initially out of revenge, [Max] now feels obliged to cooperate with the Jewish Brigade. Its members pursue and kill members of the Schutzstaffel without the knowledge of the British army, but are careful to ensure that their involvement in the Holocaust is always confirmed beforehand by two independent sources so that no innocent people are killed.

Right. Hence the torture and murder of the former official we met earlier. One naturally wonders who or what else might qualify as an independent source.

I recently read a book by Heinrich Pflanz, a local historian from Landsberg, on the infamous “war criminals” cemetery there. Pflanz did in-depth research into the trials that got these men executed, often quite brutally, or downright murdered when they weren’t dead after a botched hanging. Again and again, the documents he quotes speak of confessions being extracted through torture, and death sentences being passed thanks to “independent sources” — for the most part “professional witnesses,” as the documents call them: petty criminals, both German and foreign, who earned a quick buck by telling outrageous lies in court against men they had never seen before.

Like Spielberg in Munich — and, let’s be honest, many others in many films, TV series, and video games — the brothers Paz try to ease the viewers’ dismay at what they are witnessing by inserting the evil Nazi type calling them dirty Jews before he gets his brains blown out. Another victim, when asked to confess his guilt, answers: “No one is innocent. Not me, not you.”

They find one of their victims already hanged, a sign on his neck bearing the inscription “Nakam.”

Except the guy isn’t quite dead yet, as they find out in a cheap horror movie scene before they put him out of his misery.

The Jewish Brigade already knows about the “dark, dangerous” Nakam, a fellow revenge group that operates even outside what the Brigade considers the law. Unlike the Brigade, Nakam does not distinguish between guilt and innocence, but considers all German equally guilty.

The German who for some reason feels the Jewish Brigade is not innocent attacks them with the shovel he is using to dig his own grave and tries to get away. Max is saved by a shadowy figure who tackles and strangles the guy with bare hands — and turns out afterwards to be a woman half his size. Please.

Anna (Sylvia Hoek) is part of the Nakam, which now introduces itself to the Jewish Brigade. Their leader is Abba Kovner, played by Ishai Golan, who looks nothing like the real person. Kovner was a weasel-faced young man at the time, while Golan is a grizzled older actor.

Shortly after, Michael announces to Max that the Brigade is being sent to Belgium, as the British know about their activities in Germany. Michael is resigned to the fact that what the Brigade had been doing was just “a drop in the bucket. We’ll never get them all.” But as Michael is about to become respectable and join Haganah, a paramilitary organization, he is now charged with stopping Nakam. Max feels the members of Nakam might trust him and offers to help Michael locate them and find out about their plans.

The setting then moves to post-war Nuremberg. Strangely, the majority of people we see clearing away heaps of rubble are men, not women, like in reality. The men, for the most part, were still in captivity. The Trümmerfrauen have therefore become iconic images of the time portrayed in Plan A.

Max goes about his mission rather bluntly: He writes “Nakam” on a wall and settles down to wait. After a few days, he notices a woman taking an interest in the graffiti. She of course turns out to be Anna, his rescuer from the woods. When Max follows her to a partly-ruined apartment building where Nakam has its lair, he gets captured and interrogated. The avengers trust him enough to let him stay the night at their place, but tell him he has to leave in the morning.

Not so easily discouraged, Max follows some members of Nakam in the morning to the Nuremberg waterworks and manages to pass himself off as a plumber and hydraulic engineer in order to get a job. This scene is ridiculously over the top. The lady in charge suspects Max with good reason to be lying about his qualifications. (Which was pretty normal at the time, as people were desperate to find jobs.) When she is about to turn him away, he goes into a spiel about how he had been fighting in the service of the Reich, protecting the race — and of course that does the trick.

Now, did Germans at the time help each other out, especially soldiers, and even so-called war criminals? Yes, they did. There is an anecdote my father once told me, who must have heard it from his mother, as he was still very young at the end of the war. A Waffen-SS soldier was trying to evade the American troops who had occupied my hometown in order to get home to his family. A local farmer gave him civilian clothes and drowned his uniform in the cesspool where it was certain no patrol would search. “Anybody would have done the same,” my father said. While I’m skeptical about that, it does illustrate that ordinary Germans back then looked after one another in the face of the Allies. But they certainly didn’t make a song and dance about “the race.”

The ridiculousness continues when the foreman of the waterworks gives a pep talk about bringing water back to a “great nation.” The members of Nakam realize that Max now has access to the filtration center and the well for drinking water, and so they keep him around. He gradually finds out that Nakam is planning to poison the drinking water not only of Nuremberg, but also of other major cities in Germany. Michael is appalled when he learns of this; he urges Max to stop the plan, because if it succeeds,“The world will look at us differently, and we won’t get our country.” I’m so tempted to comment on this, but let’s move on.

Max, still torn between revenge and morals, reveals his own demons, harking back to an earlier scene when a member of the Jewish Brigade had asked him why the European Jews had never fought back. Max now reflects on the role he had in Auschwitz, that of a “greeter” for new arrivals. He smiled at them, he tells Michael, and assured them he would look after their suitcases, and having been reassured, they went to the gas. Meanwhile, Max looted their baggage for food. Max wonders why he didn’t warn them. Why didn’t he tell them to run?

The film now centers more on personal connections for a while. We learn about Anna and her frequent nightmares, which are about her seven-year-old son who drowned when she tried to escape with him from the ghetto through the sewers. Another member of Nakam has lost his faith (Dr. Jones’ “God died at Auschwitz” trope), as we can surmise from the Shabbat scene. Max is befriended by a co-worker, a former soldier who utters his disgust for Hitler when he learns that Max had been “stationed” at Auschwitz. At one point, the Nakam members notice a commotion outside and are informed by their neighbors that “they are starting to come back.” When asked whom they mean, it’s of course “Jews. They think they own everything.” Naturally, the Jews get beat up by the locals, at least as far as the scene implies; it might just be the other way around. I can’t tell.

That scene is only topped by one that might well fall into the category of “Holocaust porn,” albeit with a twist. Max and Anna go to the cinema where, probably realistically, the newsreel is all about the concentration camps and more than five million prisoners gassed. While Max urges her to watch, Anna can’t stand it and flees. Max catches up with her, and they are both so distraught that they have sex right there and then. I don’t even want to decipher the meaning here.

It turns out to have been a bad idea, anyway, as Michael uses the encounter to blackmail Max into finally getting the job done. “Germany is not a safe place for Jews,” Michael muses, and goes on about what a shame it would be if something were to happen to Anna.

Meanwhile, Kovner travels to Palestine to procure the poison for Nakam’s plan. The rest of the group have now come to the realization that they probably shouldn’t kill the occupying forces along with the Germans, and they are marking the pipes leading to the Allies’ quarters so they can block them off when things get real. Anna’s flashlight dies during the operation, and she breaks down screaming as the memories of her son’s death overwhelm her in the dark. When Max and another contender for Anna’s affection bring her home, they run into an incensed mob of neighbors who have found out they are living under one roof with Jews and are, of course, ready to fetch the pitchforks.

But it’s not another pogrom that gets Nakam, but Michael and the Haganah. They storm the apartment; the group tries to flee, but gets caught. Max then tricks Michael with an old letter from Kovner, saying that nobody in Palestine is willing to supply Nakam with poison. Strangely, the synopsis on Wikipedia puts the whole scene in an entirely different context, claiming that Max “deceives the Nakam with a false letter and thus prevents Plan A from being carried out,” which is definitely not the case. Michael swallows the lie and gives a moving speech about a new start in Palestine, where farmers till the fields and children are being born: “a whole new generation that knows no fear. That’s the real revenge.”

The members of Nakam nod their heads and, as soon as Michael and his men have disappeared, get on with their plan. Kovner, it turns out, has been able to procure the poison after all, and is on his way back. But Anna has had enough. After her breakdown, she can’t stomach the idea of children dying, even German children. She is leaving for Palestine, “where we belong,” she tells Max. “No more deaths.” She asks him to come with her, but he refuses.

With the other two members of their cell having gone to welcome Kovner upon his return, it is up to Max to guard the apartment. And here we get into what Dr. Jones — I know I’m quoting him generously — calls “the dream trope . . . Was it all real or not? Left behind and still struggling with which path to take, Max finally opens Avram’s bundle: Pandora’s box.

Kovner returns with the poison, and they head out for the waterworks. It appears to be New Year’s Eve, as there are fireworks, and people are running around with flares, making it look like some good old Nazi parade. This is probably intentional. Michael and his men show up; Kovner manages to pass the poison to Max before being arrested, and Max makes his way down to the well. Michael once more tries to stop him; there is a fight, and Max strangles him. He then pours the poison — a black, tar-like substance — into the water before drowning himself in it.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

That is not how Plan A went in real life, of course, and so, after his ritual death, so to speak, we find Max back at the apartment, staring into the black void of Avram’s empty bundle. The imagery here is quite interesting.

In reality, Max’s voiceover tells us, Kovner was arrested on his way back to Germany. And while Max often imagined “the poison flowing through the veins of Germany,” for him, that was the end. He made aliyah to have a good life in newly-founded Israel: “That was my revenge.” We then see some of the real-life members of Nakam in their old age in Israel.

And this, according to the film, is how it all ended. There is no mention of Kovner trying a second time, getting arrested a second time and then locked up in Egypt for two months. There is no mention of the fact that, as even Wikipedia noticed, where there’s a Plan A, there is a Plan B.

But before we get to that, let’s continue with the rest of the German Wikipedia entry:

Filming took place in Marktredwitz, the Fichtelgebirge, and the Steinwald from October 25, 2019 to November 15, 2019. Filming also took place in Ukraine and Israel. Around 4.4 million euros were budgeted for the total production costs. Plan A received 750,000 euros in funding from the FilmFernsehFonds Bayern. The distribution funding from the same fund and the German Federal Film Board totaled 95,000 euros.

Dina Porat, the chief historian of the Yad Vashem memorial, was attached to the film production as a consultant. Her book Vengeance and Retribution Are Mine about the Nakam served as the basis of the film. Global Screen and Verve sold the rights to Menemsha Films for distribution in the USA and Canada, and to Signature Entertainment for broadcasting rights in the UK, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand.

I’ll spare you the review quotes, because so much could be said about them, and I don’t want to turn this into the rant I feel it would invariably become.

The thing that probably struck me the most about Plan A was the “Never again” motto of Max’s Nakam cell. Now, I’ve been brought up with the understanding — and there are a number of Jewish eyewitnesses who I believe are sincere (some of them are or were advocates for the Palestinians) who attest to it — that this slogan was meant in a much wider, pacifistic way: Never again a genocide. Of course, that is not the meaning Nakam and their like gives it. To them, it means “Never again will we go like sheep to the slaughter.” That still makes no sense in the context of killing the Tätervolk after the fact, but I suppose logic and terrorism don’t go hand-in-hand.

Is Plan A propaganda? I’m not sure. It is, I suppose, as much propaganda as Munich, and that didn’t work out so well. We certainly have very few instances of Germans not coming across as fanatical Nazis, but the Jewish characters are not so likeable, either. At best, the film can plead “circumstances.” That is exactly what it tries to do, of course, as seen for example in the trailer featuring Max’s words from the beginning of the film: “What if I told you that your family had been murdered for no reason at all? Now ask yourself: What would you do?” The fact of the matter is that very few people would actually go and wipe out the perpetrator’s family plus others, but this question is purely aimed at invoking an emotional response. As it turns out in the end, Max’s answer is not murder, either.

Which finally brings us to Plan B. Instead of indiscriminately poisoning the inhabitants of Germany’s main cities, Nakam had to switch to an alternative plan because of Kovner’s failure to deliver the necessary poison. The Nuremberg cell, depicted in Plan A, focused its efforts on former SS members and Wehrmacht soldiers held in prisoner of war camps. The poison was produced closer to home, in Paris, and smuggled into Germany. Since the bread for the camp came from a single bakery, Nakam managed to get several of its members into positions both in the bakery and in the camp. It was decided to paint the poison onto the black bread the prisoners were issued. Because of unforeseen circumstances — the bakery workers went on strike — Nakam had neither the time nor the inside operatives to carry out the full plan; instead of 14,000 loaves, they “only” managed to poison 2,000-3,000 loaves.

According to the New York Times, 2,283 German prisoners of war fell ill with the effects of poisoning, and 207 were hospitalized. It is unknown how many men actually died. Wikipedia quotes Stephen Fritz’s Endkampf: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Death of the Third Reich as claiming that “the operation ultimately caused no known deaths.” E. Michael Jones, on the other hand, quoting from Michael Bar-Zohar’s The Avengers, claims that “700 or 800 died in the next few days.” Fortunately, again from the Jewish perspective, “others became paralyzed and died during the year,” bringing the final toll up to around “1,000 deaths altogether.”[3]

Interestingly, according to Wikipedia,

In 1999, Harmatz and Distel appeared in a documentary and discussed their role in Nakam. Distel maintained that Nakam’s actions were moral and that the Jews “had a right to revenge against the Germans.” German prosecutors opened an investigation against them for attempted murder, but halted the preliminary investigation in 2000 because of the “unusual circumstances.”

We can all imagine how that decision came about. Still, I’m impressed the prosecutors dared to go as far as they did in the first place. They didn’t even make the attempt in 2023.

Notes

[1] His spelling in German Wikipedia is “Mikhail,” weirdly enough. Germans are quite capable of pronouncing the faucal spelled as “kh” in English and “ch” in German. So if anyone wanted to make it clear that “Michael” is not pronounced in the English way here, but rather in the Hebrew way (mi-cha-el, “who [is] like God”), they should have done so in the English Wikipedia.

[2] E. Michael Jones, The Holocaust Narrative, pp. 383-287.

[3] Ibid. p. 108.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to editor@counter-currents.com. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

4 comments

A local farmer gave him civilian clothes and drowned his uniform in the cesspool where it was certain no patrol would search. “Anybody would have done the same,” my father said. While I’m skeptical about that, it does illustrate that ordinary Germans back then looked after one another in the face of the Allies. But they certainly didn’t make a song and dance about “the race.”

I know that many Bavarians helped the soldiers of the so-called Eastern Legions (Özbeks, Qazaqs, Türkmens) to hide, when Allied soldiers searched for them. Some of those soldiers and officers even married Bavarian women, like the famous Ruzi Nazar, in the future one of the prominent CIA officers and personal friend of some Türkish politicians. His daughter Sylvia Nasar, half-Özbek and half-Bavarian, is a well-known American writer, she is best known for her biography of John Forbes Nash Jr., A Beautiful Mind, for which she won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography.

Later the Britisch and American authorities proved, that soldiers of the Eastern Legions were not guilty in any war crimes, were just front soldiers, not more, and so the search for them stopped and they were allowed to go to the US and another countries. But before of this some of them were shipped by Western democrats to GULAG.

Thank you for the article. Very interesting.

That should have been written as “machiavellian extreme ethnocentrism” instead of “morals”

Much more brutal history comparing to another film, Es war einmal in Deutschland.

Comments are closed.

If you have a Subscriber access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.