Against Liberalism:

Society Is Not a Market,

Chapter I, Part 2: What Is Liberalism?

Alain de Benoist

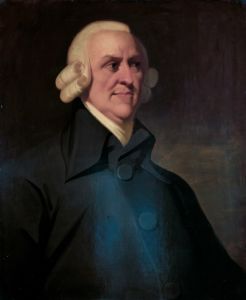

The Scottish economist Adam Smith, who understood the ways in which the market would transform human relations already at the dawn of liberalism.

3,287 words

Part 1 of 3 (Introduction Part 1 here, Chapter I Part 1 here, Chapter I Part 3 here)

Translated by F. Roger Devlin

Liberalism must, however, recognize the fact of society. But instead of asking why the social realm exists, liberals are mainly preoccupied with understanding how society is able to establish itself, maintain itself, and function. Society, as we have seen, is for them nothing but the sum of its members (the whole is nothing but the sum of its parts). It is nothing but the contingent product of individual wills, a mere assemblage of individuals all seeking to defend and satisfy their particular interests. This society can be conceived either as the consequence of an initial rational voluntary act (the fiction of the “social contract”) or as the result of the systematic interplay of all the actions produced by individual agents, an interplay regulated by the “invisible hand” of the market which “produces” the social realm as the unintentional result of human behavior. The liberal analysis of social reality thus rests upon either the contractual approach (Locke), or recourse to the “invisible hand” (Smith), or the idea of a spontaneous order not subordinate to any design (Hayek). The essential goal of society, according to liberals, is to regulate relations of exchange. In the end, it is a mere market.

All liberals develop the idea of a superiority of regulation by the market, which is supposedly the most effective, most rational, and therefore also most just way of harmonizing exchanges. At a first approach, then, the market presents itself as an “organizational technique” (in the words of Henri Lepage). From an economic point of view, it is both the real place where commodities are exchanged and the virtual entity where the conditions of exchange are formed in an optimal manner; i.e., the adjustment of supply and demand, as well as price levels. (From this point of view, there obviously cannot be any salary too high or too low, nor any abusive price, which permits the dismissal of any critique on this subject as “emotional.”) As for the optimal functioning of the market, it involves nothing interfering with the free circulation of goods and services, men, and commodities; i.e., borders are considered non-existent. Whence the cosmopolitanism inherent in liberal capitalism, which is also the principle of free trade: “Laissez faire, laissez passer!” (This is also why employers have always ardently defended immigration, to which it has recourse all the more gladly in that it allows downward pressure on salaries.[1])

But liberals do not ask about the origin of the market, either. Just as man is supposedly “naturally” oriented toward the search for his best interest, commercial exchange is for them the “natural” model for all social relations. It follows that the market is also a “natural” entity, defining an order prior to any deliberation and any decision. Constituting the form of exchange most conformable to human nature, the market is supposedly present from the dawn of humanity in all societies — which is obviously false, for in traditional societies the dominant logic is that of gift and counter-gift (defined by the triple obligation to give, to receive, and to pay back). For the physiocrats, Frédéric Bastiat, and Jean-Baptiste Say, for example, capitalism is an economic system born of the most natural human penchant, the market itself constituting the most “natural” form of exchange. (One wonders, then, why it did not appear earlier!) This is also what Alain Minc naïvely states: “Capitalism cannot collapse; it is the natural state of society. Democracy is not the natural state of society. The market is [sic].”[2] We find here the tendency of any ideology to “naturalize” its presupposition; in other words, to present itself not as what it is, a construction of the human mind, but as mere description, a simple transcription of the natural order.[3] With the state simultaneously rejected as artificial, the idea of a “natural” regulation of the social realm by way of the market is free to impose itself.

You can buy Alain de Benoist’s Ernst Jünger between the Gods and the Titans here.

By understanding the nation as a market, Adam Smith carries out a fundamental dissociation of the concept of space from that of territory. Breaking with the mercantilist tradition that still identified political territory with economic space, he shows that the market cannot by nature be enclosed within specific geographic limits. The market in fact is not so much a space as a network. And this network is called upon to expand to the limits of the Earth, since in the end its only limit resides in the impossibility of exchange. Smith writes in a celebrated passage:

A merchant . . . is not necessarily the citizen of any particular country. It is in a great measure indifferent to him from what country he carries on his trade; and a very trifling disgust will make him remove his capital, and, together with it, all its industry which it supports, from one country to another.[4]

These prophetic lines justify Pierre Rosanvallon’s declaration that Adam Smith was the “first consistent internationalist.” “Civil society conceived as a fluid market extends to all men and allows the divisions between countries and races to be overcome,” he adds.

The concept of the market’s principal advantage is that it allows liberals to resolve the difficult question of the basis of obligation within the social contract. The market can in fact be considered as a law that regulates the social order without any legislator. Regulated by the action of an “invisible hand,” itself naturally neutral since it is not incarnated in concrete individuals, it institutes an abstract form of social regulation founded on objective “laws” supposedly providing for the regulation of relations between individuals without any relationship of subordination or command between them. The economic order is thus called upon to realize the social order, with both being definable as something that emerges without having been instituted. Since universal utility is no more than the aggregation of the utility of individuals, we simultaneously postulate the natural and spontaneous harmonization of interests. As Milton Friedman says, the economic order is “the unintended and unwilled consequence of the actions of a large number of persons moved only by their interests.” This idea, which was extensively developed by Hayek, is inspired by Adam Ferguson’s formula (1767) referring to social facts that “derive from the action of man, but not from his design.”

Smith’s metaphor of the invisible hand is well-known: In seeking “only his own gain, . . . he is . . . led by an invisible hand to promote an end that was no part of his intention.”[5] This metaphor goes well beyond the banal observation that the results of men’s actions are often very different from what they were counting on (what Max Weber called the “paradox of consequences”). In fact, Smith places his observation within a resolutely optimistic perspective, writing:

Every individual is continually exerting himself to find out the most advantageous employment for whatever capital he can command. It is his own advantage, indeed, and not that of the society, which he has in view. But the study of his own advantage naturally, or rather necessarily, leads him to prefer that employment which is most advantageous to the society.[6]

This metaphor’s theological connotations are obvious: the “invisible hand” is merely a secular avatar of Providence. But it must be specified that contrary to what is often believed, Adam Smith does not assimilate the very mechanism of the market to the action of the “invisible hand,” for he only has the latter intervene to describe the end result of the totality of market exchanges. Moreover, Smith also admits the legitimacy of public intervention when individual actions alone do not succeed in realizing the public good. But this restriction will quickly disappear. Hayek forbids on principle any global approach by the society: no institution, no political authority may assign itself goals that might cause the beneficial functioning of “spontaneous order” to be questioned.

Under such conditions, the state cannot have any purpose proper to itself. The only role most liberals agree to attribute to it, apart from respect for the laws and individual rights, is to guarantee the necessary conditions for freedom of exchange; i.e., the free play of economic rationality at work in the market. From this point of view, the state must put itself at the service of the individual and his “freedom of choice,” beginning with his right to act freely according to the calculation of his own private interests. It becomes the gendarme, manager, “night watchman,” or arbiter of private interests, endowed not so much with functions as with attributions, and obliged to abstain from any intervention in economic and commercial affairs, it must remain neutral in all other domains and renounce proposing any model of the “good life” (Aristotle[7]), for that would amount to favoring the conceptions of some men to the detriment of the conceptions of others. Society must be ruled by principles that do not presuppose the superiority of any private conception of the common good, each individual being supposed to be free to live according to his own private definition of “happiness.” (In the historical context in which liberalism emerged, this principle was considered a means of doing away with wars of religion.)

The result is that with the arrival of the market, as Karl Polanyi writes, “society [is run] as an adjunct to the market. Instead of economy being embedded in social relations, social relations are embedded in the economic system.”[8] Commercial exchange, which was formerly only one mode of human activity (and not considered especially important), becomes the foundation and general rule of civil society. The Homo oeconomicus then being in the service of the economy and not the other way around, quality gives way to quantity (“you are what you have”).

The consequences of the theory of the “invisible hand” are decisive, especially on the moral level. From its first formulations, liberalism makes everyone’s prosperity rest upon the egoism of each, exhorting individuals not to respect a sense of proportion and limits, but rather to abandon themselves to pleonexia, the unlimited thirst for having. Egoism thus becomes the best way of serving others. As Adam Smith says: “By pursuing his own interest, [man] frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.” This is the viewpoint developed by Bernard Mandeville in his celebrated Fable of the Bees (1705): private vices, public benefits. In other words, virtue proceeds from vice, good proceeds from evil; we are already in the world of Orwell. (It should be noted, however, that this Mandevillian idea that private vices are the causes of public happiness amounts to thinking that the public action of individuals is equivalent to their private action — the negation of the distinction between public and private which liberalism claims to maintain elsewhere.) Frédéric Bastiat sums up this viewpoint in the formula: “Everyone, by working for himself, works for all.”[9]

From the moral point of view, this is a revolution. With this doctrine, liberalism rehabilitates the very forms of behavior that past ages had always condemned. By affirming that the interest of society is subordinate to the economic interest of individuals, and that by seeking to maximize our personal interest we are working without realizing it — and without even wanting it — in everyone’s interest, it makes egoism the best way of serving others. Since the free confrontation of egoistic interests in the market allows “naturally, or rather necessarily” their harmonization by the play of the “invisible hand,” which will make them work together toward the social ideal, there is nothing immoral in seeking one’s own interest first of all, because in the end the egoistic action of each will contribute to the interest of all. Thus, in the end egoism is nothing but altruism properly understood. And it is the actions of public authority that deserve to be denounced as immoral every time they (under the pretext of solidarity) contradict the right of individuals to act in view of their interests. What is called the axiomatics of interest is simply the translation into philosophical terms of this egoism which liberalism legitimates at the highest level. This is also the foundation of the metaphysics of subjectivity (Heidegger). It is a system that negates the common good in a double sense, since it rejects the concept of “the good” as well as of “the common,” to say nothing of the bond between these two words.

Liberalism binds individualism and the market by declaring that the free functioning of the latter is also the guarantor of individual freedom. By assuring the most profitable result of exchanges, the market guarantees the independence of each agent. Ideally, if the proper functioning of the market is not hampered, this adjustment will be carried out in the optimal fashion, allowing the attainment of an ensemble of partial equilibria that define the global equilibrium. Defined by Hayek as “catallaxis,” the market constitutes a spontaneous and abstract order, the formal instrumental support of the exercise of private freedoms. Thus the market represents not only the satisfaction of an ideal of economic optimality, but the satisfaction of everything to which individuals (considered as generic subjects of freedom) aspire. Finally, the market blends with justice itself, which leads Hayed to define it as a “game which increases the chances of all players,” before adding that under these conditions the losers have no right to complain and have only themselves to blame. Finally, the market is supposedly intrinsically “pacifying,” since it rests on “gentle commerce” which, substituting negotiation for conflict as a matter of principle, thereby neutralizes rivalry and envy.

You can buy Anthony M. Ludovici’s Confessions of an Anti-Feminist here.

We see here that for liberals the concept of the market goes well beyond the economic sphere. A mechanism for the optimal allocation of scarce resources and a system for regulating production and consumption cycles, the market is also and above all a sociological and “political” concept. Adam Smith himself, insofar as he designates the market as the commercial order’s principal operator, is led to conceive relations between men on the model of economic relations; i.e., as relations with merchandise. The market economy thus naturally follows in the market society. As Pierre Rosanvallon writes, “The market is first of all a way of representing and structuring social space; only secondarily is it a decentralized mechanism for regulating economic activities through the price system.”[10]

For Adam Smith, generalized exchange is the direct consequence of the division of labor: “Every man thus lives by exchanging, or becomes, in some measure, a merchant, and the society itself grows to be what is properly a commercial society.”[11] Thus the market is indeed, in the liberal view, the dominant paradigm in a society called upon to define itself in all its parts as a market society. Liberal society is merely a place of utilitarian exchanges participated in by individuals and groups motivated exclusively by the desire to maximize their own interest. A member of this society where anything can be bought or sold is either a tradesman, an owner, or a producer, and always a consumer. As Pierre Rosanvallon writes, “The superior rights of consumers are to Smith what the general will is to Rousseau.”

In the modern era, liberal economic analysis will be gradually extended to all social facts, as if analyzing a social fact economically (which is always possible) were enough to transform it into an economic fact. Privatized and deinstitutionalized, the family is assimilated to a small company, social relations into an interlacing of competing self-interested strategies, and politics into a market where voters sell their vote to the highest bidder. Man is perceived as capital, a child as a durable consumer good. Individuals are called upon to become managers of themselves in a thoroughly commercialized society. Economic logic is thus projected onto the whole of society in which it used to be embedded, with every form of human relation presumed to function under implicit conditions of contract and competition.[12] As Gérald Berthoud writes, “Society can then be conceived on the basis of a formal theory of purposeful action. The cost-benefit ratio thus becomes the principle that makes the world go round.”[13] Everything becomes a factor of production or consumption; everything is supposed to result from the spontaneous adjustment of supply and demand. Everything is worth what its exchange value is worth, as measured by its price. And at the same time, everything which cannot be expressed in quantifiable and calculable terms is considered either uninteresting or non-existent. Economic discourse thus proves itself deeply concretizing of social and cultural practices, and deeply foreign to any value not expressible in terms of price. Reducing all social facts to a universe of measurable things, it finally transforms men themselves into things — things interchangeable from the point of view of money.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] It is not an accident that Laurence Parisot, then President of Medef [Mouvement des entreprises de France, an employers’ association], launched an appeal in Le Monde (April 17, 2011) for France to “remain an open country that profits from mixture.” Jean-Claude Michéa writes: “Putting workers in competition with one another — of which the summoning of foreign workers is merely one form among others — has always constituted the most effective weapon at the capitalists’ disposal (along with the formation of what Marx called ‘the reserve industrial army’; in other words, a permanent brigade of the unemployed) for exercising a continual downward pressure on salaries, and thus increasing their own profits” (Notre ennemi, le capital. Notes sur la fin des jours tranquilles [Paris: Climats, 2017], 151).

[2] Cambio 16, December 5, 1994.

[3] This pretention has long been criticized. Cf. especially Karl Polanyi, La grande transformation : Aux origines politiques et économiques de notre temps [1944] (Paris: Gallimard, 1983); and Réné Passet, L’illusion néo-libérale [2000] (Paris: Flammarion-Champs, 2001). But there are disagreements on this point among liberal authors. Not all believe in the existence of a human nature, despite the difficulty of speaking of “rights of man” under such conditions, and Hayek interprets the market as literally against nature, which in his eyes is a reason for valuing it!

[4] An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book III, Chapter 4.

[5] Ibid., Book IV, Chapter 2.

[6] Free trade, as theorized in the last century by the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson model (cf. Bertil Ohlin, Interregional and International Trade [Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933], also rests on the belief in an “invisible hand,” as well as on Ricardo’s principle of an international division of labor and the postulate of the possibility of a “pure and perfect competition” (or “free and undistorted competition”). It has been shown many times that at the macro-economic level these beliefs are illusory and that the universalization of free trade ends in the ruin of political sovereignties; the dismantling of the state’s capacity for action; the strengthening of the dominant positions and the widening of inequalities, dislocations, and the moving of industry to countries with low costs; and the universalization of social, fiscal, and environmental dumping, the concentration of wealth, the withering of food crops, etc. Cf. Arthur MacEwan, Neo-Liberalism or Democracy? Economic Strategy, Markets, and Alternatives for the 21st Century (New York: Zed Books, 1999).

[7] Concerning the role of the state, such is the most common liberal position today. Libertarians (also known as “anarcho-capitalists”) go farther, since they reject even the “minimal state” proposed by Nozick. Not being a producer of capital, while it does consume labor, the state for them is necessarily a “thief.”

[8] The Great Transformation, op. cit., 60.

[9] Harmonies économiques (1851).

[10] Op. cit., 124.

[11] [Wealth of Nations, book I, ch. 4.] Cf. e.g., Bertrand Lemennicier, Le marché du marriage et de la famille (Paris: PUF, 1988); Privatisons la justice. Une solution radicale à une justice inefficace et injuste, (Nice: Ovadia, 2017).

[12] Op. cit., vol. 1, 92.

[13] Vers une anthropologie générale. Modernité et altérité (Geneva: Droz, 1992), 57.

Against%20Liberalism%3A%0ASociety%20Is%20Not%20a%20Market%2C%20%0AChapter%20I%2C%20Part%202%3A%20What%20Is%20Liberalism%3F%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

A Short Note on Satire

-

A Puzzling Situation or The Story of a Young Man

-

Havens in a Heartless World

-

Leftist Rhetoric: Unoriginal and Repetitive

-

Trčanje pred rudo: O zabludama desničarskoga trećesvjetaštva

-

Society vs. the Market: Alain de Benoist’s Case Against Liberalism

-

Decadence, the Corruption of Status Hierarchies, and Female Hypergamy: A Response to Rob Henderson’s Article “All the Single Ladies” pt 2

-

Decadence, the Corruption of Status Hierarchies, and Female Hypergamy: A Response to Rob Henderson’s Article “All the Single Ladies”

1 comment

One of my very favorite explanations of liberalism (incl economic angle)

a 6 min vid by Stefan Verstappen–

From yt because it keeps getting deleted from bitchute and worldtruth:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K528aCSi-Rg&t=6s

Comments are closed.

If you have a Subscriber access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.