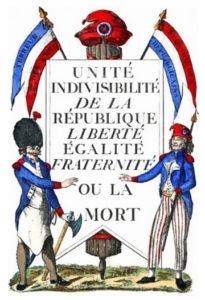

The holistic society of the Middle Ages, as embodied in the “Three Orders of Mankind,” began to be broken down by the coming to prominence of the marketplace with the rise of nation-states.

4,142 words

Part 3 of 3 (Introduction Part 1 here, Chapter I Part 2 here)

Translated by F. Roger Devlin

This strictly economic representation of society has considerable consequences. Finishing off the process of secularization and “disenchantment” of the world that is characteristic of modernity, it results in the dissolution of peoples and the systematic erosion of their particularities. At the sociological level, the adoption of economic exchange leads the society to be divided into producers, owners, and sterile classes (such as the former aristocracy) at the end of an altogether revolutionary process. (more…)