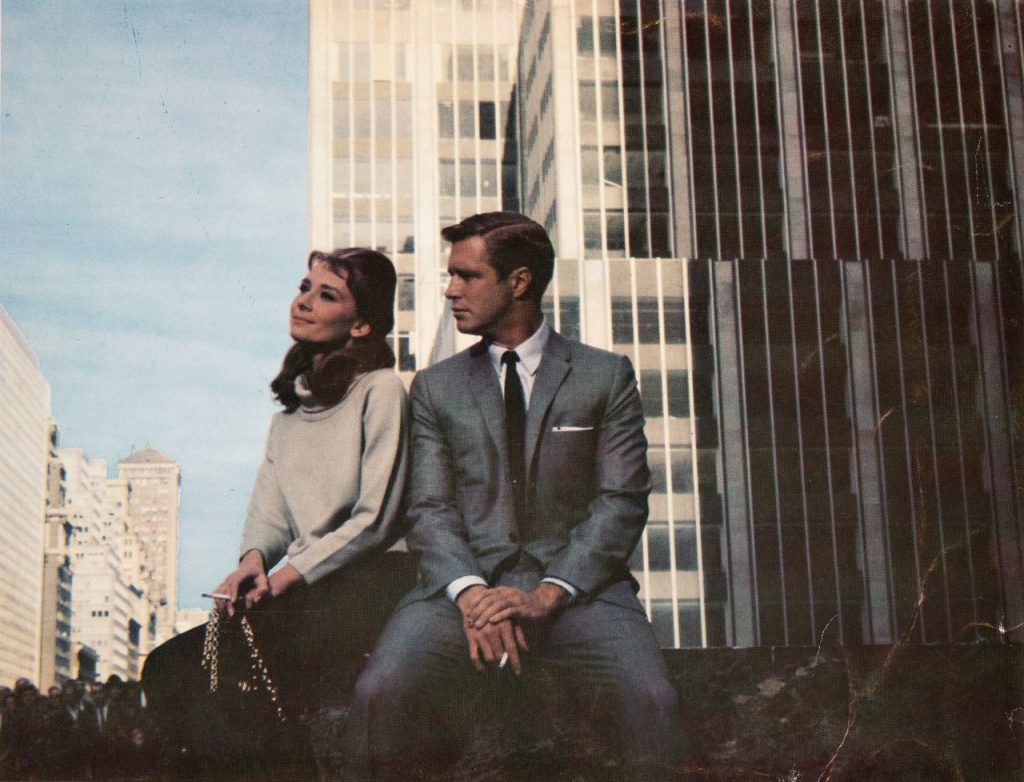

Blake Edwards’ 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s—loosely based on Truman Capote’s 1958 novel of the same name—stars Audrey Hepburn in her iconic role of Holly Golightly, a charming, flighty, feminine, haunted young woman trying to create a life—and an identity—in a gorgeous Technicolor New York City at what is arguably the peak of American civilization, just before the plunge.

I have seen Breakfast at Tiffany’s six times, twice on the big screen, and although I loved it every time, for the first four viewings, the movie played a strange trick on my memory. If you had asked me what Breakfast at Tiffany’s was about, I would have said it is a wholesome romantic comedy. But that’s not really true. Yes, it has plenty of comic elements, but overall, Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a very sad and serious film. As Sally Tomato says, the story of Holly Golightly’s life would be a book that “would break the heart.” That’s certainly true of Truman Capote’s novel, which is indeed so heartbreaking that Blake Edwards rewrote the ending for the movie to give us a little hope to cling to.

And, as for wholesomeness, it has that too in the end. But somehow I repeatedly forgot that Breakfast at Tiffany’s is the tale of the romantic misadventures of two gold-diggers, Holly Golightly and her upstairs neighbor, Paul Varjak, both of whom are skating through their 20s by having sex with and taking money from older and richer people. Of course, they both maintain their self-respect by keeping a discreet distance between the sex-giving and money-taking, so that the quid pro quo is not too brazenly obvious. Capote said that Holly stopped short of simple prostitution, describing her as an “American geisha.”

Both Holly and Paul rationalize their choices by reference to a mission. Holly wants to buy land and horses and care for her sweet but slow brother Fred, who is currently in the Army. (The novel is set in 1943, so being in the army is rather dangerous undertaking.) Paul is a writer who needs a patron to give him time to work on his great novel. But it is not working. He’s got writer’s block. As Holly notes, he doesn’t even have a ribbon in his typewriter.

Paul is the prouder and more serious of the two. Holly is top banana in the flake department. Which, of course, means that Paul suffered greatly at Holly’s hands when he falls in love with her.

Maybe the false memories are due to Henry Mancini’s music, which won two Oscars, for best score and best song for the haunting cornball classic “Moon River,” with lyrics of Johnny Mercer, which casts a silvery shimmer of nostalgia over the whole heartbreaking tale. Whatever the cause, I am grateful to this amnesia, for it has allowed Breakfast at Tiffany’s to surprise me again and again with each new viewing.

The basic plot of Breakfast at Tiffany’s is quite simple. Paul Varjak—played by George Peppard at the peak of his Nordic-preppy good looks—moves into an apartment on Manhattan’s upper east side and meets his ditzy downstairs neighbor, Holly Golightly. Holly has lived there for a year but looks like she is still moving in. That’s because she’s rootless, a drifter, a flake. She has an orange cat, but she hasn’t given him a name, because she doesn’t want the commitment. Her favorite place in the world is Tiffany’s, the jewelers on Fifth Avenue. She declares to Paul that if she ever finds a place that makes her feel like Tiffany’s, she’ll put down roots and give the cat a name. Of course it is hard to imagine a home that would feel like Tiffany’s. Buckingham Palace, perhaps? Holly, in short, is not too practical. Her conditions for settling down are a fanciful way of saying “never.”

Paul’s apartment isn’t exactly “him” either. It looks like an expensive European hotel room. It was decorated before his arrival by his patron, Mrs. Failenson, nicknamed “2E,” played by a radiant Patricia Neal (who once played opposite a certain Ellsworth Toohey in King Vidor’s film of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead). The movie creates the character of Paul from the novel’s unnamed narrator. 2E and her relationship with Paul are inventions of the screenwriter, which considerably deepens the character and his relationship with Holly, creating dramatic conflict through “irreconcilable similarities.”

Holly finds Paul to be a sympathetic, useful, and highly presentable neighbor. As fellow gold-diggers, they also have a certain understanding. But in her eyes, their shared mode of life also precludes a relationship, for Paul has no gold, and Holly has set her sights on older, uglier men with more money. For Paul, gold-digging is a short-term strategy, to get his start in life, at which time he will settle down with a nice girl and take care of her. For Holly, however, gold-digging is a long-term strategy to find a husband, who will take care of her forever.

One of the most captivating sequences in Breakfast at Tiffany’s is when a mysterious stalker shows up outside Paul and Holly’s building. 2E thinks her husband is having her followed. Paul, who is a red-blooded male under his gorgeous wardrobe, is game for a confrontation. After a game of cat and mouse in the east side and in Central Park, the stalker approaches Paul and says, “Son, I need a friend.”

It turns out that the stalker, played by Buddy Ebsen, is Doc Golightly, a veterinarian from Texas and Holly’s . . . no, not her father, her husband, whom she married at the age of 14. Holly’s real name is Lula Mae Barnes. Lula Mae and Fred were runaways who showed up on Doc’s farm. Doc was a widower with children who needed a helpmeet. Hence the marriage. Doc has tracked Lula Mae down to persuade her to return home to “her husband and her chirren.”

Holly will have none of it. The marriage was annulled long ago, and she’s just not Lula Mae anymore. She has constructed a whole new identity for herself. She got rid of her Okie accent with French lessons, courtesy of a Hollywood producer, O. J. Berman (Martin Balsam), and she has a fabulous circle of rich male friends—whom she rates as “rats” and “super-rats”—competing for her attention.

When she sees a heartbroken Doc off at the Greyhound Bus station, she tells him that she’s a “wild thing” and that one should never fall in love with wild things, because they will just break your heart. In truth, Holly is just a flake who doesn’t know who she is or what she wants and is afraid of real relationships and real commitments. Berman thinks Holly is a phony, but he debates whether she is a real phony or not—a real phony being someone who believes his own nonsense.

The whole sequence moves from creepy, to comical, to corny, to deeply moving. That’s the magic of this film.

Once Doc has been sent on his way, Holly gets roaring drunk. It is a catharsis, a crisis, a crossroads. Paul now knows her story but loves her all the more. He hopes that she will get a little more serious about life, and maybe about him. Paul enjoys taking care of Holly. It makes him feel strong and manly. Being taken care of by 2E is convenient but emasculating. Unsurprisingly, Holly proves to be the better muse than 2E. Awakening Paul’s manliness also awakens his creativity.

Thus Paul is appalled when Holly declares that she is no longer going to play the field. She is going to set her sights on marrying Rusty Trawler, the ninth richest man in America under fifty, despite the fact that he is a tittering pig-faced manlet. (In the novel, Trawler is a known Nazi sympathizer who once proposed marriage to Unity Mitford.)

When Trawler falls into the clutches of another gold-digger, Holly coolly turns to pursuing José da Silva Pereira (played by Spanish aristocrat José Luis de Vilallonga), a dashing but strait-laced Brazilian from a prominent family. It is not clear to Paul, though, if he means to marry her or merely keep her as a mistress. Holly is oblivious, however.

Whatever José’s intentions, however, he calls it off when Holly is arrested. Holly has received $100 per week to visit Sally Tomato, an elderly mobster incarcerated at Sing Sing, and deliver his “weather report”—obviously coded messages about the narcotics trade—to his people outside.

Berman gets Holly bailed out. Paul packs her belongings and the cat and picks her up at a police station to take her to a hotel where she can hide out from the press. In the cab, he breaks the bad news about José. While adjusting her lipstick, Holly coolly decides to jump bail, use her ticket to Brazil, and marry some other rich South American. In an act of consummate bitchcraft, she tells the cab to pull over and abandons the cat in an alleyway in a downpour. In the novel, she follows through with her plan and disappears. A realistic but terrible outcome that puts Holly Golightly into the lower circle of flaky heartless bitches like Cabaret’s Sally Bowles.

In the film, Paul gives Holly a powerful talking to. He tells her that people really do belong to one another and that it is the only real chance we have of happiness. In today’s rabidly individualistic society, these are unfashionable sentiments, but deeply romantic and stirring ones. Paul actually reaches Holly. He actually changes her heart. She runs into the rain, searching for the cat, whom she finds, then Paul and Holly embrace, the prototype of a human family that may come to be. (Holly definitely wants children.) The end—a happy one, we hope.

Unsurprisingly, modern arbiters of virtue don’t like Breakfast at Tiffany’s very much. It is obviously heteronormative, anti-feminist, and otherwise “problematic.” But their ire is focused mostly on Mickey Rooney’s portrayal of Holly’s upstairs neighbor, Mr. I. Y. Yunioshi, as a buck-toothed Jap buffoon, straight out of World War II propaganda cartoons. Frankly, even I am offended by Mr. Yunioshi. Capote’s novel makes much more of race, but it is hard to say if it is “problematic” or “woke.” For instance, Holly notes that José has a touch of black blood. But she doesn’t mind the prospect of having slightly “coony” babies as long as the father is rich and respected. (Eventually, they’ll come for Capote as well.)

Unsurprisingly, modern arbiters of virtue don’t like Breakfast at Tiffany’s very much. It is obviously heteronormative, anti-feminist, and otherwise “problematic.” But their ire is focused mostly on Mickey Rooney’s portrayal of Holly’s upstairs neighbor, Mr. I. Y. Yunioshi, as a buck-toothed Jap buffoon, straight out of World War II propaganda cartoons. Frankly, even I am offended by Mr. Yunioshi. Capote’s novel makes much more of race, but it is hard to say if it is “problematic” or “woke.” For instance, Holly notes that José has a touch of black blood. But she doesn’t mind the prospect of having slightly “coony” babies as long as the father is rich and respected. (Eventually, they’ll come for Capote as well.)

I highly recommend Breakfast at Tiffany’s. But what is most enchanting about this film can’t be captured in prose. It simply must be seen—for the beautiful people, the iconic fashions (one of the little black dresses Audrey Hepburn wore in this film fetched nearly one million dollars at auction), and its portrayal of a glamorous, safe, overwhelmingly white New York City.

Watch it as nostalgic, escapist entertainment—a mid-century American time capsule. I’m betting you’ll want to re-watch it as a character study that even manages to have a “message”—and a wholesome one at that. It communicates the joys and follies of youth in America at its peak—an age of seemingly infinite potential—and the necessity of finally growing up and actually taking a stand, of actually being someone. It became the road less traveled.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

7 comments

I never saw Breakfast at Tiffany’s and probably never will, but I did see Butterfield 8, the 1960 movie based on the 1935 novel by John O’Hara and starring Elizabeth Taylor, Laurence Harvey with an appearance by Eddie Fisher. Elizabeth Taylor won her first Academy Award for her performance in this film in which she played a glamorous call girl who is involved in an illicit affair with the richest man in town. She ultimately kills herself in a car accident.

Frankly it was a mediocre movie with a terrible script. I think they ran out of money before they hired a screenwriter and just made it up as they went along. I saw this film while I was channel surfing on TV one night.

It was incredible, not because of any great screenwriting or any acting.

It was incredible because it showed American civilization at its high water mark, as portrayed by its all white, English speaking cast. No garbage and homeless people camped out in the streets. In one scene, Elizabeth Taylor is shopping for a birth day gift for her married lover and is assisted by a sales woman in an upscale department store. It’s Eve Arden, of “Our Miss Brooks” fame. Amazing! A sales woman who’s white, who speaks fluent English, who is familiar with the merchandise and who is attractive and well groomed. How different from today.

Then Elizabeth Taylor gets into a cab and the cab driver is a white, English speaking clean American! Amazing!!

How far have we sunk when it’s a great uplifting sight to see clean, English speaking WHITE people competently performing such menial jobs as sales clerks and taxi cab drivers? Pretty damned far.

Old movies are snap shots of a long dead WHITE America in its glorious grandeur. How interesting that such mundane scenes as decent even if humble people treating each other well as an example of greatness and grandeur of a now dead civilization.

I’m old enough to remember the 50’s and 60’s and department stores and cabs and other proletarian places and institutions that were so wonderful unlike now.

A couple of days ago I had breakfast at a McDonalds where I had to repeat my order three times to the non-White behind the counter who could barely speak English. It’s that way everywhere now. I’m waited on by foreign, alien non-Whites who can barely speak English and who are horribly ignorant of their jobs. They know nothing of what they’re selling. Try to get directions at a gas station now? Forget it.

The Downtown Abbey movie premiered to full houses. I think one draw of that series and that movie is the humanity of the people, the use of proper English and the pride in their jobs that they take.

Elizabeth Taylor won the 1960 Oscar for Butterfield 8 not because of the excellence of the movie or her performance, but because the consensus was that she’d deserved it for her part in Suddenly, Last Summer the previous year.

The novel Butterfield 8 is a fine piece of work, John O’Hara’s second novel, but it’s set in the 1930s. Gloria Wandrous throws herself off an old paddlewheel night boat to New Bedford. These steamboats were a regular fixture of New York–New England travel, but by 1960 they were long gone. Dying in an auto accident is no substitute.

When Breakfast at Tiffany’s and Butterfield 8 are adapted to a setting circa 1960, it eviscerates the whole mood and cluster of intangibles that animated the original fictions.

Thanks for responding. I agree that adaptations of novels by movies into different historic times really are not faithful, but they don’t necessarily need to be. The novels, unadapted, are still there for us to read and enjoy.

I’ve never read either the O’Hara novel, Butterfield 8, or the Tennessee Williams play, Suddenly Last Summer, which was a one act play. A lot of ground in one act.

Superior to Butterfield 8 is O’Hara’s first, Appointment in Samarra. A marvelous, quick read that stands up very well 85 years later. I strongly recommend it.

After that, move on to his later novella trilogy, Sermons and Soda Water.

John O’Hara wrote about a hundred more novels and a thousand more short stories (many of which are still sitting in drawers at The New Yorker), but I exaggerate, if only slightly. Almost all were variants on his early work.

No one’s ever done a good film adaptation of Butterfield 8 or any film adaptation at all of Appointment in Samarra. If you read these things you see what brilliant material is there, if the scenarist absolutely insists that these things be set and cast properly in 1931-1934.

In late-50s Hollywood there were B.O. successes with From the Terrace and Ten North Frederick (bringing Paul Newman and Suzy Parker, respectively, to the silver screen), but these still didn’t have the proper 1930s Gibbsville spirit.

What a nice reply.

I saw a few John O’Hara adaptions, such as Butterfield 8 and 10 North Frederick, but never read a single word of any of his prose. I shall have to start. Although I only recently saw Butterfield 8 on TV, I did see 10 North Frederick in the theater as a child with my parents. It was a little above my emotional and intellectual level at the time, but I did enjoy it even though I was bored by the lack of shooting and WW2 action scenes, which were the staple of my favorite movies at that age.

Thankfully I grew up and can fully appreciate 10 NF now. I never realized it was John O’Hara adaptation, but because of your post I’ll certainly re-watch the movie and try to get a copy of the book.

I’ve been researching debut novels that were both: (1) best sellers and (2) movies. After seeing The Talented Mr. Ripley and then reading the novel, by Patricia Highsmith, I learned that her debut novel, Strangers on a Train, was both a best seller and a film, the rights having been purchased by Alfred Hitchcock. I wondered how often that could possibly happen, that the debut novel, the first published novel, of a newbie novelist could hit a double header like that, by being both a best seller and a movie?

Well to my surprise it’s actually fairly common. Examples of such modern double headers are: Gone with the Wind (Margaret Mitchell), Paths of Glory (Humphrey Cobb), Raintree County (Ross Lockridge), Peyton Place (Grace Metalious), Tales of the South Pacific (James Michener), Cool Hand Luke (Don Pearce), Executive Suite (Cameron Hawley), A Kiss Before Dying (Ira Levin), The Big Sleep (Raymond Chandler), The Sun Also Rises (Ernest Hemingway), It’s a Wonderful Life (Philip Van Doren Stern), Magnificent Obsession (Lloyd C. Douglas), The Graduate (Charles Webb) and many, many others.

Unfortunately, John O’Hara didn’t make that elite club because, as you point out, his debut novel, Appointment in Samarra, has never been adapted to a motion picture even though it was a best seller that firmly established his reputation. Perhaps one day it will be adapted.

You say he wrote more than 100 novels? That’s a lot but I can’t find any support for that. Your sources are probably better than mine, you obviously being a committed JO fan.

Based on your enthusiasm and recommendation, I shall certainly have to read at least some of his books now, most definitely Appointment, Butterfield 8 and 10 North Frederick. The last thing I need at this stage of my life is another addiction or obsession, but since swearing off TV and movies, I’ve not only saved a lot of money but have obtained a lot more time for reading and research and I will try to fit in time for JO books.

Reading up on JO, I read that he was a political conservative and suffered from life long insecurity because he couldn’t afford to go to college. Hemingway once said, cruelly, that they should take up a collect for John O’Hara so that he could go to Yale. Little did JO know how lucky he was to have been blessed with genuine talent rather than with money and connections to go to a vastly overrated school alone side members of the Bush family. Yale could very well have snuffed out his natural creativity and burdened him with college loans.

None of us is perfect and the measure of us as people is how well we meet the challenges of an imperfect world I guess. John O’Hara seems to have met them very well, notwithstanding the lack of a degree from Yale or any other college.

Hahaha! I just saw Downton Abbey, and I couldn’t help being grateful for how gloriously White it was (I’d never seen the TV series), though I was disappointed at the presence of a gay subplot. The new and unbelievably obnoxious cinematic trend is to place nonwhites even into European historical pictures (see the appalling and badly written “Mary Queen of Scots” from earlier this year, which hit many different PC obsessions, including, again, the obligatory gay character (this one of ‘color’), whom the heroine ‘understands’ and ‘accepts’).

It was good to discover this article, Trevor. just a few of my observations. First, Jewish Hollywood can’t resist getting in digs against white Southerners. Holly is sexually immoral, but then , as a “Shiksa” what would you expect.? Holly is a Call Girl, and Paul is a Gigolo.- the most morally righteous man in the film is Doc Golightly, who by today’s standards would be the worst-a pedophile! It’s good for us to consider how the Left has changed American mores since 1959. Roy Moore ran into this problem in his bid for U. S. Senator from Alabama several years ago I remember a joke from my childhood that seems appropriate here-What do they call a 16 year old girl in Arkansas? answer-middle aged.” By today’s standards the best man in the film has become the worst-Holly and Paul’s peccadilloes are between “consenting adults”, and therefore ok under the now prevailing standards set by the Sexual Revolution of the Sixties-nothing to see here! But then, Doc Golightly is a white Southerner and therefore worthy of vilification. 16 will get you 20 today, but not then. Finally, I agree with Don’s comment about the unintended portrayal by Hollywood of the superior American Civilization of the 50’s and early 60’s. On point I watched the early 50’s movie “Violent Saturday” recently. Jewish Hollywood ‘s intended hidden subtext was to show how hopelessly flawed the supposedly upright goyim of small town America actually were back then, but what struck me was a portrayal of a clean scrubbed gang of bank robbers wearing suits and ties, looking like aristocrats compared to the bank robbers of today. Ever wonder why we never see a Jewish villain in a Hollywood movie?-they’re all, like Berman in Breakfast at Tiffaniy’s, astute observers of goyim foibles and flaws, kind of a greek chous wryly noting, ‘”What Fools these mortals be!”

Comments are closed.

If you have a Subscriber access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.