Yukio Mishima (1925–1970) was one of the giants of Japanese letters as well as an outspoken Right-wing nationalist. Mishima shocked the world on November 25, 1970, when he and members of his private militia, the Tatenokai or Shield Society, took hostage the commander of the Japan Self-Defense Force’s Ichigaya Camp. Mishima then delivered a speech to the assembled soldiers and press, exhorting the Japanese to turn away from American-imposed consumerism back to their traditional aristocratic culture, which prized honor above life and comfort. Then, to show that he really meant it, Mishima committed ritual suicide along with one of his followers, Masako Morita.

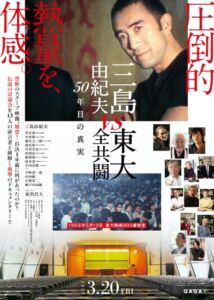

Mishima: The Last Debate, directed by Keisuke Toyoshima, focuses on an event that took place on May 13, 1969: Mishima’s debate with the radical student protest group, the All-Campus Joint Struggle Committee or Zenkyoto, which had mounted violent protests against the government, the educational system, and the American occupiers. Interestingly enough, Zenkyoto was anti-communist as well as anti-capitalist and anti-American. They drew more inspiration from phenomenology and existentialism than from Marxism.

Mishima despised Marxism and probably would not have debated communists. But Zenkyoto’s third positionist stance overlapped significantly with his own Right-wing nationalism. Thus he accepted the invitation to debate in the hope of winning over some of the students. This was not a Quixotic hope, given that the Shield Society consisted mostly of college students.

The debate took place in Lecture Hall 900 of the University of Tokyo in front of an audience of 1,000 including Mishima’s Tatenokai security detail. The event lasted two hours and was filmed by the broadcaster TBS. The footage was long thought lost. When it was rediscovered, it was given to Toyoshima to create a documentary, which runs for 1 hour, 51 minutes and incorporates 45 minutes of debate footage plus contemporary news footage of student unrest and recent interviews with debate participants and eyewitnesses, as well as academics and two prominent novelists. The novelists are Mishima’s friend Jakucho Setouchi, a Buddhist nun who was 97 years old at the time of the interview, and Keiichiro Hirano, an outspoken admirer of Mishima. The film is fundamentally respectful of Mishima and all other participants in the debate. The documentary premiered in Japan in late 2020, and only now has a version subtitled in English leaked onto the internet.

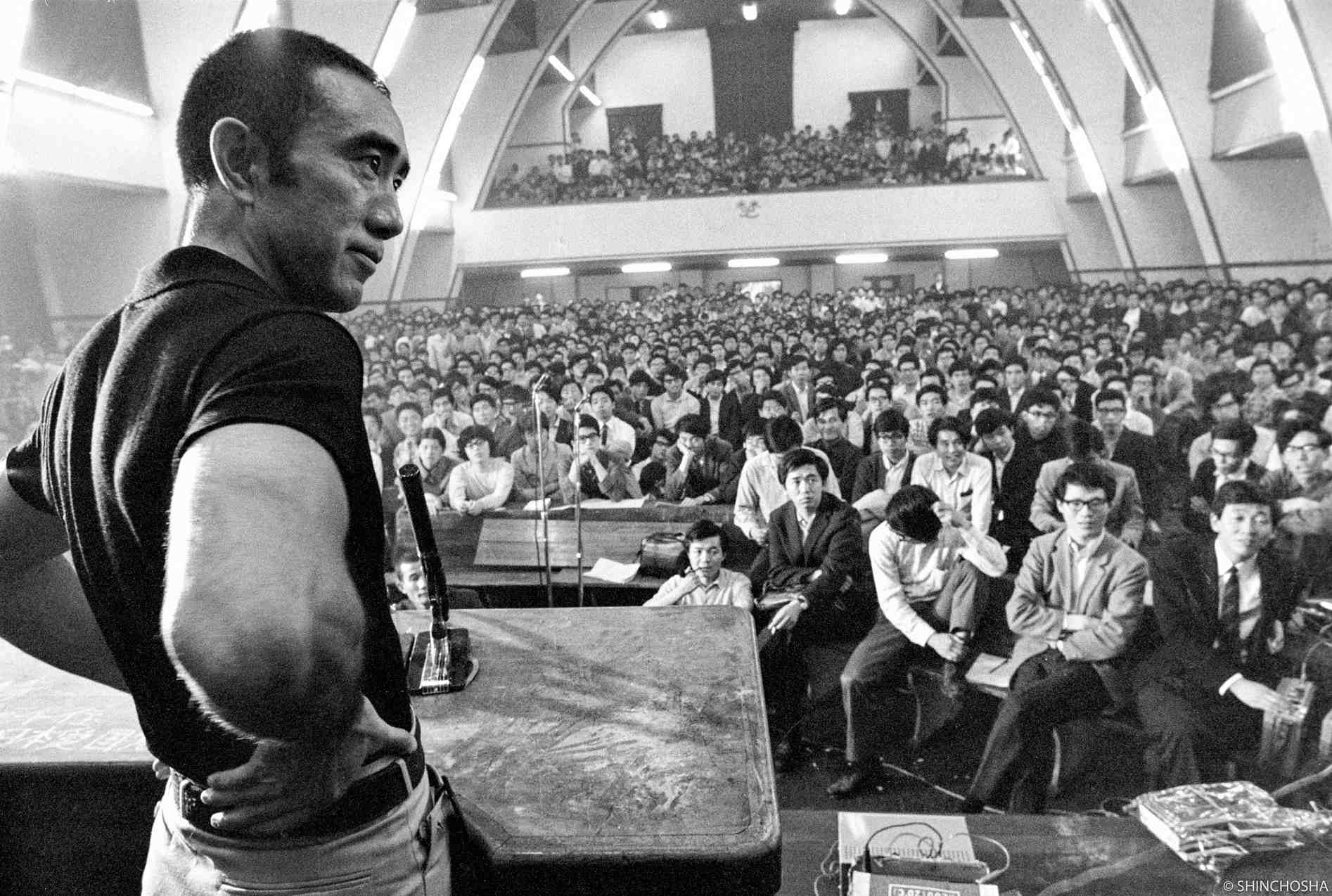

Mishima’s performance in the debate is masterful. Dressed in black polo and white slacks, he is conspicuously fitter and more stylish—and even more youthful—than the students, who are half his age but often look frumpy, slovenly, and defensive. Mishima is remarkably diplomatic and respectful in dealing with the students, even when they are rude and abrasive. He is relaxed throughout: smoking, laughing, and cracking jokes with the audience. He seeks to find common ground and then bring the students around to his way of thinking.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here

Mishima could win on charisma alone, but his arguments are even more impressive. He knows his phenomenology and existentialism better than the students yet keeps his remarks firmly grounded while his interlocutors often float away in abstractions. At the 29-minute mark, Mishima answers a question about the status of the “other” in his thought that is the high point of the film. He begins by saying that he hates Jean-Paul Sartre—probably because he was a communist—then explains Sartre’s phenomenology of the obscene as objectification in Being and Nothingness—bringing the house down with a joke about the Prime Minister—before arguing that non-objectifying relationships with others are fraught with the potential for enmity and violence, which of course give rise to the political. He states that when he wished to move away from a literature that merely objectified others, he had to choose an enemy, which for him is communism. It is a rather deft transition from abstract philosophy to concrete Rightist politics.

There’s a good deal of back and forth between Mishima and a hippy actor and director named Masahiko Akuta, who shows up with his infant daughter in his arms. Akuta is often quite muddle-headed and overly abstract. He frequently comes off as a phony. But Mishima patiently tries to interpret Akuta’s remarks and respond to them. Akuta is also quite rude at times, but Mishima never takes umbrage.

When Akuta brings his arguments down to earth, it is usually in the form of accusations premised on goofy cosmopolitan pieties. “You are nothing without Japan,” he asserts, to which Mishima replies by inventing the “yes” meme in 1969: “That’s me.” When Akuta accuses Mishima of being unable to transcend being Japanese, Mishima says, “That’s okay.” As Akuta waxes cosmopolitan, Mishima just responds, “Ah so,” holds out the microphone, and lets Akuta dig himself into a deeper hole.

Mishima defends his Japanese identity as simply a fact, as a destiny that cannot be avoided. His only choice in the matter is to own up to it or not. In Heidegger’s idiom, being Japanese is Mishima’s “thrownness,” and owning up to that fact is “authenticity.” By contrast, Akuta’s claim that one can transcend one’s nationality is inauthenticity: phoniness. We do not create our identities, nor can we recreate them, but try telling that to an actor. Mishima is quite comfortable with philosophical abstractions, but being a novelist, he is also masterful at making them concrete. At one point, he tells the audience that if they don’t know what it means to be Japanese, they need to go abroad for a spell.

Mishima makes frequent reference to the emperor, telling the students that he would have joined their movement if they had mentioned the emperor just once. At one point, he states that the students are wrong to think the emperor is “bourgeois.” The bourgeois ethos places life and comfort above all else, whereas the aristocratic ethos embodied by the emperor puts honor above life and comfort. Mishima recounts how the emperor presided over the graduation ceremony of his elite high school, remaining as rigid as a statue for three hours. Mishima wished to communicate that there is an aristocratic critique of bourgeois society from above, not just the Marxist critique from below.

The documentary ends with Mishima’s suicide, which includes actual footage from Mishima’s final speech plus the announcement that he and Morita had killed themselves. I did not know that this footage existed, and although it was brief, I found it surprisingly moving. I hope it will be the seed of its own documentary. Many of the soldiers who heard Mishima are alive today. I would like to know their thoughts after more than fifty years.

I was also quite amazed to see interviews with three members of the Shield Society, all of them in their 70s, as well as to learn that they still meet every November 25th to honor Mishima and Morita. As one would expect, they are a very dignified lot.

Several things are remarkable about Mishima’s debate. First, it is carried on at a very high level of abstraction, with remarkable earnestness. Today’s student radicals are inane and infantile by comparison. Second, Mishima’s performance is impressive in both substance and style. Third, it is astonishing that such a meeting took place at all, although in the 1960s, George Lincoln Rockwell was invited to speak on American university campuses. Such events would never happen in academia today. If they were scheduled in the first place, they would rapidly be shut down by angry mobs.

At the beginning of the debate, Mishima says he is there to test whether words can still bridge the gap between opposed political camps. It was possible at the University of Tokyo in 1969. It scarcely seems possible today, but the documentary itself proves that it is. When Toyoshima was offered the project, he had a one-sided and negative image of Mishima. Thus when he viewed the footage, he was shocked at Mishima’s graciousness, humor, and fair-mindedness. I think he tried to emulate these qualities in the film, with great success, since it is scrupulously decent and respectful in its portrayal of all parties. Mishima: The Last Debate is an excellent documentary. I recommend it highly to anyone interested in Mishima, Japanese culture, and radical politics where the extremes really can meet from time to time.

The Unz Review, July 27, 2021

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

The Fall of Minneapolis

-

Alain de Benoist k populismu

-

I’m On Team Normal

-

The Bikeriders

-

A Million Questions Why: Sacrificing Liberty

-

The Witness: How Lies about Kitty Genovese’s Murder Were Used to Undermine White America

-

The Dead Don’t Hurt: A Viking Western

-

Home of the Hits: My Top 10 Hitman Movies

7 comments

Unfortunately the link to the English-subtitled version of the film has already been deleted. If someone finds it, or info on a paid version, please post it!

If I find another version, I will.

If you’re a Mac user, it’s on Apple TV.

https://mega.nz/file/6lgySQDR#diuh-lAAiDexCIQVAi3sQietOkAj615soVcJM0jeCLw

Thank you. Is this download perfectly safe? Anyone attempted it?

Excellent review, btw. Though I wish Lynch would elaborate on the following:

“At the 29-minute mark, Mishima answers a question about the status of the “other” in his thought that is the high point of the film. He … explains Sartre’s phenomenology of the obscene as objectification in Being and Nothingness … before arguing that non-objectifying relationships with others are fraught with the potential for enmity and violence, which of course give rise to the political. He states that when he wished to move away from a literature that merely objectified others, he had to choose an enemy, which for him is communism. It is a rather deft transition from abstract philosophy to concrete Rightist politics.” (italics mine)

I don’t understand what is being said in the italicized portion.

Chiming in to say thank you for providing this.

Thank you for pointing to a great documentary. I will definitely look this up (thanks also to the above poster with the link)

Zenkyoutou and “Japanese” communists were mostly run by overt and crypto koreans with strong ties to N Korea and China (not just Soviets)

In the article it says “third positionist views of Zenkyoutou had much in common with nationalism.”

But could it be perhaps that nationalism is by nature third positionist, and by being so – it often inadvertently facilitates communist advancement?

Mishima as a nationalist found affinity and a “common goal” with the Zenkyoutou communists in Tokyo who at the time raised banners that read “OPPOSE both! Anti Soviet AND Anti USA! Oppose imperialists!”

That’s China talking.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment