I have been wanting to write a review of Die große Liebe (The Great Love) for years. I read that it had the distinction of being the most popular movie in the Third Reich, and that got me curious. The only Nazi films that anyone has ever heard of are two that are discussed far out of proportion to their actual popularity at the time: the Hitler infomercial Triumph of the Will and Der ewige Jude, a helpful and informative public service announcement about the Jewish menace lurking in the shadows of Europe. As much as you hear about those two films, very few Germans actually saw either of them at the time. I wanted to see a Nazi movie that the average German actually watched and enjoyed.

According to Wikipedia, Die große Liebe, released in 1942, is some sort of romance movie. When I read that, I became really curious. I wanted to see what a Nazi romance movie looks like. You can kind of guess what a Nazi war movie or a Nazi historical drama would be like, but what the hell does a Nazi love story look like?

Finding a complete version of the film with English subtitles was difficult, however. I was able to find an English subtitled version of Wunshkonzert, the second-most popular movie in the Third Reich. But lo and behold, after much searching, an English-subtitled version popped up on YouTube recently. Hopefully, it doesn’t get taken down by the time you read this, but in case it does, I found another copy on Bitchute. Here’s the trailer:

Die große Liebe did not sound all that propagandistic from the plot summary, but having watched it a couple of times now, it is a propaganda movie through and through — although it’s not at all what you might think of when you hear the phrase “Nazi propaganda.” If you are expecting a movie with lots of dastardly Jews and honorless Brits, you will be disappointed. If you want a “based” Nazi movie, you’d probably be happier watching Jud Süß (which actually was quite popular with the German public) or the 1943 anti-British propaganda film Titanic (considered by Titanic experts to be one of the most historically accurate of the many films made about the sinking). But Die große Liebe isn’t like them. There really isn’t much of a political message, and it doesn’t even really have a villain or any unsympathetic characters.

Rather, it is propaganda aimed mainly at women about the virtue of standing by their men in a time of war. That’s not to say that Die große Liebe is a “chick flick.” Men may be entertained by the film, but given that the female lead is the one who has the most dramatic character arc, it’s clear that to the extent the film has a message, it’s directed at women.

Germany had a need for such propaganda at the time. It was in the interest of the war effort not to have German women dumping their boyfriends or cheating on their husbands while they were away at war. Sometimes the only thing keeping a man going while he’s on the front lines is the thought of seeing his hometown sweetheart again and feeling her warm embrace. If a fella finds out that his Fräulein back home has been getting the bratwurst from ol’ Hans at the sauerkraut shop around the corner, that’s bad for morale.

Of course, it was no picnic for Germen women, either. Their men were often away for indefinite periods of times, and even when they did meet again, it was usually only briefly. A lady gets lonely. And even with conscription, there were still a lot of available single men in Germany: older men, men who got military exemptions because of their trade or medical condition, the foreign nationals working in Germany, and so on. So it behooved the German government to produce some propaganda for women that made staying loyal to their military men look cool, noble, and elegant, while also portraying the military men as the ideal romantic who is best to choose over whatever options were available. (The aforementioned film Wunshkonzert also contained themes of “love interrupted by war.”) Thus, the film is about loyalty as much as love.

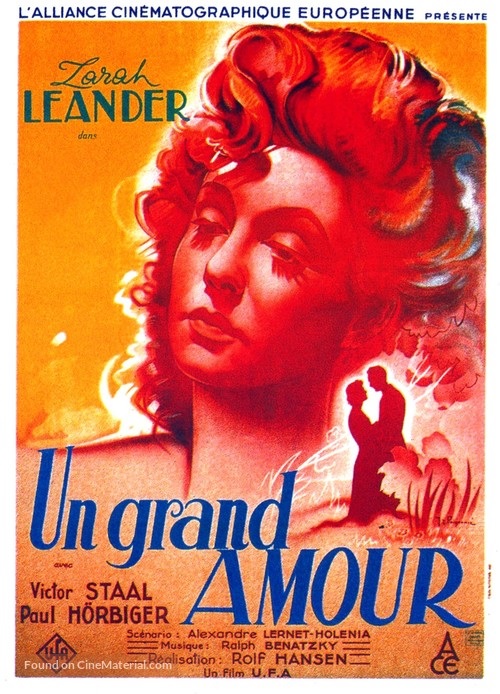

Die große Liebe stars Swedish singer/actress Zarah Leander as Hannah Holberg, a popular Danish singer who spends the most of the movie fending off wealthy suitors and stage-door Johnnies while she awaits the fleeting returns of her fighter-pilot boyfriend while he’s off trying to save the world from the Jews. “I would wait weeks, months for an hour with him,” she declares. “One hour of happiness makes up for everything, for all the sorrow.”

Leander was possibly the most popular entertainer in National Socialist Germany, both for her films and her music. She is sometimes called “the Nazi Garbo,” and she does indeed bear a passing resemblance to Greta Garbo from certain angles, although her smokey-voiced singing style is more likely to draw comparisons to Marlene Dietrich. Leander’s music has remained popular throughout the decades. Nico from the Velvet Underground — who was reported by her friends to be a raging anti-Semite in private — was a big fan, and pioneering East German new wave musician — a phrase I don’t get to use very often — Nina Hagen wrote a song in tribute to Leander.

Leander appeared in several propaganda movies throughout the war. In the 1940 anti-British film Das Herz der Königin (The Heart of the Queen), Leander played Mary, Queen of the kind-hearted Scottish people and rightful heir to the British throne who is later executed by the wicked ice queen Elizabeth I of the cruel English. In Der Weg ins Freie, she plays an Italian opera singer who leaves her German husband and winds up with a Slavic Count who turns out to be a real son of a bitch. Leander’s true political beliefs are anyone’s guess. She’s been accused of being everything from a Nazi sympathizer to a Soviet spy. Leander herself claimed that she was just an entertainer.

Leander’s leading man in Die große Liebe is the lantern-jawed Viktor Staal. Most biographies describe him as Austrian, but he was more specifically a Sudeten German born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in what is now the Czech Republic. Five years prior, Staal co-starred with Leander in her breakthrough film Zu neuen Ufern (To New Shores), a “women in a penal colony” movie set in nineteenth-century Australia.

In this film Staal plays the charming Luftwaffe fighter pilot Paul Wendlandt. Wendlandt is interesting because he is presented as the National Socialist ideal. Rather than being the Hollywood stereotype of a humorless stiff or a raving fanatic, he is a man who both works and plays hard. In his free time, he can be playful or even a bit mischievous — at one point, he bullshits his way into a stranger’s party in order to continue pursuing Leander — but is unwaveringly committed to his duties when it comes down to business. He has the elegance of a gentleman, but is not an elitist. He is a man of the people who treats the common folk with the same warmth he shows to glamorous Scandinavian chanteuses.

The third lead is Paul Hörbiger, who plays Leander’s eternally friendzoned musical Svengali Alexander Rudnitzky. I’ll spare you the Googling and tell you that yes, Rudnitzky is — or at least can be — a Jewish name. Most of the famous people I could find named Rudnitzky and its variations were Jewish, but this character is not Jewish; he is an archetypical Slavic composer, possibly a White Russian.

Rudnitzky is the musical brains behind Hannah’s singing career. He writes all her songs and handles the business side of her career. He is also madly in love with Hannah, but is unable to get with her — partly due to his cheating wife refusing to grant him a divorce, but primarily due to Hannah’s general disinterest in him as anything more than a close confidante. Rudnitzky is the closest thing Die große Liebe has to a villain in that he tries to keep Hannah and Paul apart, and eventually resorts to deception to do so. Yet, Rudnitzky is not unsympathetic, and his motives for trying to break up the couple are not entirely selfish. He genuinely believes that Paul is bad for Hannah because she is prone to falling into depression and despair while he is away, which in turn affects her singing career.

Rudnitzky would be more accurately be described as a foil than as a villain. He is the stand-in for all the ol’ Hanses from the sauerkraut shops in Germany. In a lot of ways, he is the more logical and pragmatic choice for Hannah. He’s got money, he worships the ground she walks on, and unlike Paul, he can actually be there for Hannah all the time. On top of that, they work in the same field. They make beautiful music together, so why shouldn’t they also be able to make beautiful music together figuratively? Other than not being a dashing Aryan superchad such as Paul, there’s nothing wrong with him per se.

In a way, Die große Liebe is as much of a propaganda movie for ol’ Hans who might feel tempted to “comfort” the lonely home-front Fräuleins as it is for the Fräuleins themselves. Rudnitzky has to learn to let go of Hanna.

Something counterintuive should already be evident: Two of the three lead characters are not German. Leander’s Hannah Olsen is Danish, and Rubnitzky, while a German national, is a Slav. This can be explained by the fact that Germany aspired to become the Hollywood of Europe at the time. Instead of every country having their own national film industry, Germany wanted to just make movies for everyone. As such, Germans were not the only target audience for this film.

And indeed, Die große Liebe is at heart a love story about a German military man and a woman from Denmark — a country that had recently been conquered by Germany. In fact, the film has a sort of “something for everyone” quality to it — or at least something for everyone in the Axis. Germans could identify with Paul the Luftwaffe pilot. Scandinavians could identify with Zarah Leander and/or her character, Hannah Olson. Czechs and Austrians could both claim Viktor Staal as a hometown hero. And parts of Die große Liebe take place North Africa, France, and Italy — where extras can be heard speaking Italian — so moviegoers in those places could feel involved in the story as well. Hell, the movie’s even got a sympathetic Slav. You could say that Die große Liebe is an (dare I say it?) “inclusive” Nazi movie..

The film opens in North Africa. Paul Wendlandt is returning to base after a mission when one of his landing gears malfunctions and he is forced to make a crash landing. He is then sent to Berlin to report on the incident. While in Berlin, he will have one evening free — and the glorious privilege of being able to sleep late the next day before he has to ship back out to the front. For his one evening of freedom, Paul and his war buddy decide to go to the theater to see the acclaimed Danish singer Hannah Holberg. Upon seeing Hannah perform, Paul is instantly smitten, and heart-shapes begin orbiting his head. He suddenly considers it his mission to win Hannah’s love, but resolves to attempt his seduction in civilian clothes rather than the military uniform he is wearing.

The film then cuts to backstage, and we are introduced to Hannah and the two comic-relief characters: Alfred, a burly acrobatic performer who is in love with Hannah but too shy to talk to her, and Hannah’s gal-pal Käthe (Grethe Weiser), a veteran of the Weimar cabarets. A fun fact about Weiser is that she married a Jew as a teenager and had a half-Jewish son, both of whom were living in Switzerland at the time of Die große Liebe’s release. Her Jewish husband supported Weiser’s career all throughout the Weimar years, but she left him for a German UFA film producer shortly after the Nazis took power in 1934. I’m sure the manosphere crowd could think of a few things to say about that.

We see Alfred purchase an expensive bag of luxurious black-market coffee beans from a child, and he then sends the contraband to Hannah as a gift. In 1942 the average German had not consumed actual coffee in years, and so Alfred’s romantic gesture is the subject of much backstage gossip. Hannah, however, has no interest in Alfred, while her friend Käthe has a crush on him and likes to tell herself that she is the ultimate target of Alfred’s affections. But she will later abandon her interest in Alfred for an unseen soldier named Max. As Käthe later explains, Alfred “was just an ideal, but did nothing for the heart,” reinforcing the theme of the military man as the best romantic choice.

The first third of the movie is dedicated to Paul’s pursuit of Hannah, and this is where the most suspension of disbelief is required. Paul basically stalks his way into Hannah’s heart, after which she falls madly, obsessively in love with him. After leaving the theater, Paul follows Hannah onto a bus, then the subway, and when he discovers that she is not going home but to a party, he follows her there as well. Maybe this is a European thing. I know that American women who travel to Europe are sometimes shocked at how forward European men can be (Italian men are particularly famous for their directness). Let’s just say that I did not find the seduction convincing and had to suspend a lot of disbelief as it unfolded.

Hannah is initially icy to Paul, but very slowly warms to him, and seeing that she really doesn’t have much choice in the matter, agrees to let him walk her home. Upon arriving at her apartment, it would appear their night together has come to an end — but it is actually just beginning, for at that exact moment, air raid sirens go off in the distance. This means that Hannah has no choice but to invite Paul into her building — at least for the duration of the air raid.

“Oh, no,” moans Hannah. “Again, down into the basement with these terrible people . . .”

“Come on,” replies Paul. “Are these people really so terrible?”

This is a bit of foreshadowing. Here we see that Hannah is a bit of a snob who is annoyed at having to rub shoulders with the hoi polloi while Paul, a National Socialist, is a man of the people who feels kinship with the common folk.

Before they go down to the cellar, the two go into Hannah’s apartment to drop off some things and pick up others to take with them. Before making their exit, Paul and Hannah stand at the window and take a last look at the Berlin skyline before it is bombed.

Paul: Gosh, it’s beautiful, isn’t it?

Hannah: Hmm, like in fairy tales.

Paul: No, it’s much more beautiful — like reality.

Hannah: Yes. And that’s why we now must go quickly to the cellar, because in reality, there are shell splinters and bombs.

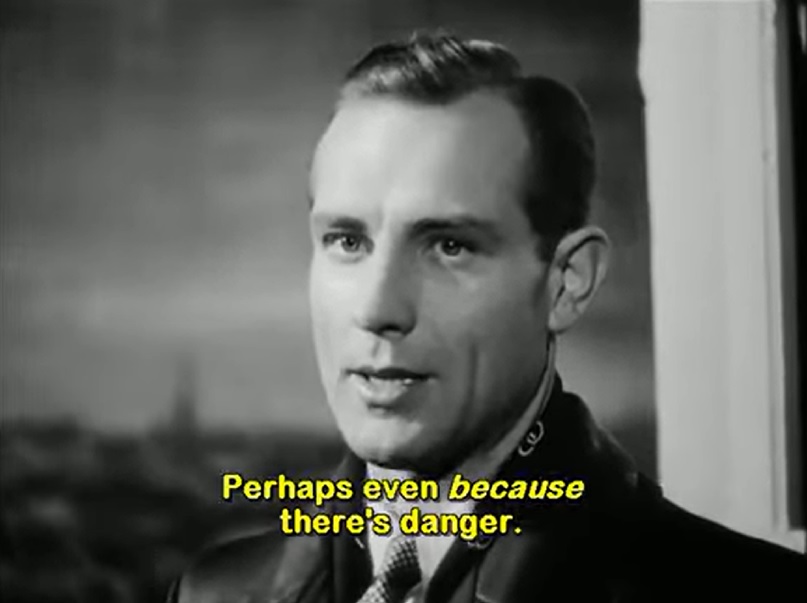

Paul: And yet reality is beautiful even if there’s danger.

Paul then gives Hannah a smoldering seductive look: “Perhaps even because there is danger.”

That is a very fascist sentiment: There is beauty in struggle and romance in war.

Hannah is still acting somewhat cold towards Paul, but once in the cellar, Paul becomes the life of the party and she starts taking a liking to him. He plays a board game with a child to stave off his boredom. When the explosions from Allied bombs begin, he calms the old grannies’ fears: “Dear ladies, don’t you worry. Let us elegantly ignore it. I suggest we now boil ourselves, with serenity, a nice cup of coffee.”

Paul takes out Alfred’s bag of black-market coffee beans. The scoffing cynic of the cellar says, “Coffee? Just spare me that old malt slop, will you?” The cynic is referring to ersatzkaffee, a kind of imitation coffee that Germans drank during the war that contained no caffeine. But once the cynic inspects the bag and finds that the beans are real, he decides that he would like some after all — but Paul refuses: “Whoever does not honor the malt is not worth the beans.” For the rest of this scene, the cynic becomes the butt of Paul’s jokes.

In the end, Hannah is not won over by Paul’s suave looks or clever flirtations but by his goodness and how he is able to bring out the goodness in others, including those she earlier described as “terrible people.” Once the air raid is over, rather than parting ways Paul stays the night at Hannah’s apartment, where they have an evening of efficient German love-making. But in the morning, Paul has vanished, having left without even so much as a verabschiedung, and for the next three weeks Hannah hears nothing from him.

By now Hannah is madly and inexplicably, obsessively in love with Paul — because she does not yet know what Paul does for a living beyond that it involves a lot of travelling. Rudnitzky tried to comfort Hannah and convince her that she is not in love with Paul, but merely has a wounded ego after getting pumped and dumped. Hannah assure him (and us) that this is not the case and that she is most assuredly in love with Paul.

After three weeks Hannah is ready to make peace with the fact that she will never see Paul again when he suddenly shows up at her apartment. Her initial reaction is one of anger, but she learns that Paul had very legitimate reasons for his silence — he had been on duty in the middle of the desert without access to a phone. He didn’t write due to slow wartime mail delivery. So why didn’t he say goodbye on the morning he left? As Paul explains to his Luftwaffe buddy Etzdorf, it’s because he hates to see women cry.

Hannah and Paul’s love affair rekindles and they enjoy a few glorious days together before Paul is once again shipped off to the front — but this time to France rather than North Africa. The next time he is on leave he returns to Hannah’s apartment, but she is in Paris performing a concert for a group of German military officers. This part of the movie establishes that it’s not just Paul’s military career keeping the two lovers apart; Hannah’s career as a touring singer is also an obstacle.

Paul then puts in a request with the Luftwaffe for some marriage leave so that he can make a respectable woman out of Hannah, and is granted three weeks. For Paul and Hannah, the idea of three entire weeks together seems like a lifetime compared to the scattered days and hours they’ve spent with each other up to that point. A wedding is planned and Hannah’s mom travels from Denmark for the event, as do Paul’s military pals. But alas, cruel fate has different plans. At the pre-wedding party, Paul receives a telegram from the top brass ordering him to return to base immediately. While Paul is certainly disappointed, Hannah is utterly crushed — but orders are orders, so she can’t blame Paul for this misfortune.

Hannah tries to get over her disappointment by throwing herself into her work. A big concert is planned in Rome which she hopes will take her mind off Paul. Paul arrives shortly before the opening of the show, and it turns out he has once again been granted three weeks leave. At last the two can finally get married and live happily ever after.

But then the stars align against Hannah once more.

Only a few minutes after reuniting, Paul gets a phone call after which he announces that he has to go back to base again. Hannah asks if this was the result of a direct order. Paul tells her it was not, but that it was strongly hinted that it might be a good idea for Paul to return to base.

Hannah is emotionally devastated for a third time. It’s one thing for their love to be interrupted by Paul’s military obligations, but this time he is leaving her when he is not even compelled to do so. Hannah runs out of the room and Paul chases after her. Rudnitzky then intervenes and pleads with Paul to give Hannah up for the sake of her emotional well-being. Paul brushes Rudnitzky aside and enters Hannah’s room. What follows is the dramatic highpoint of the film:

Hannah: You must excuse me for running away earlier, but . . . I thought I didn’t hear you right . . . When are you going to leave?

Paul: Tonight.

Hannah: And . . . without orders?

Paul: Yes. I have met a comrade — an officer from the staff who indicated to me that it would be better if I made myself available to the squadron again.

Hannah: I see. He “indicated” it. And why, may I ask?

Paul: He would not tell me.

Hannah: Oh, so he just “indicated” it, right?

Paul: Yes, and he also got me a seat on that courier aircraft.

Hannah: And now you’re just going — without reasons and without any order, and I just have to put up with the fact.

Paul: Hannah! For every hour I’m not at my squadron, another comrade has to stand in for me, has to take over my duty as well, and right now . . . Hannah! I beg you, do not torment me . . . It’s damned hard for me, too . . . Crap! But you do have to accept . . .

Hannah: No, I do not accept it. I cannot bear it any more.

Paul: What did you actually have to bear so far? The fact that I always have only little time for you? That our wedding had to be postponed?

Hannah: And that’s nothing? Just wait until they call you. You don’t even know whether you’re really needed.

Paul: Yes, I do know. I want to go. I want to go to my comrades! I beg you, don’t try over and over again to dissuade me from my decision that I consider my duty.

Hannah: And I ask you to stay at least until you get the order.

Paul: I thought you knew what it meant to become the wife of an officer.

So this is what a Nazi romance movie looks like.

There are several things about this scene that stand out. First of all, being a true National Socialist, Paul doesn’t need anyone else to order him to do what is right and honorable. That is a message that you would expect from a fascist movie. There are also the reasons Paul gives for why he must leave. Notice that he does not explain it in ideological terms (“We have to stop the Jews!”) or even patriotic terms (“the Fatherland needs me!”). Instead, when Paul talks about why he must leave, he speaks about his comrades. If Paul does not return to the front, it would put the lives of his comrades in even greater danger. This gives the movie much wider appeal than if Paul had started preaching about Hitler’s genius and the dangers of Judeo-Bolshevism.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

It must be remembered that there were still people in Germany who did not like the Nazis and/or agree that the war was justified. This would have been doubly true in the occupied nations. But loyalty to one’s comrades is a virtue that transcends culture and ideology. Everyone across the political spectrum and across the world values loyalty to one’s comrades. Even blacks admire a real nigga who’s got his homie’s back.

You will sometimes hear normies say “Joseph Goebbels would be proud of that!” in response to some preachy movie or TV show with an obvious agenda that beats you over the head with its message. In reality, Goebbels was a big believer that propaganda should not feel like propaganda. He was anti-over-the-top messaging. This scene would be an example of Goebbels’ philosophy in action: By not being overtly ideological, the film is much more effective as propaganda. It might not seem like it just from reading this review, but Die große Liebe does do a good job of not feeling like propaganda.

Back to the story. Hannah is bewildered by Paul’s militant “bros before hoes” — or perhaps I should say “mensches before wenches” – stance, and struggles to reconcile how he could possibly love her and yet chooses not to be with her when he has the precious opportunity to do so. But the very next day Hannah learns that, just as after their first encounter, Paul had a very good reason when she hears the voice of Hitler on the radio:

. . . so Moscow has not only broken the agreements of our friendship pact, but betrayed them in a cowardly way. I have therefore decided today to put the fate and future of the German Reich and our people back into the hands of our soldiers.

It turns out Paul had to leave because Operation Barbarossa was starting. Once again, Hannah is made to feel foolish for ever having doubted Paul. She picks up a pen and starts writing a letter to him:

Beloved! War with the Soviets! Now I know why you wanted to leave. I’m so embarrassed. While you risk your life at any moment, I’m not even able to wait a few weeks, a few months for you.

Alas, due to the opening up of the Eastern Front, the government has put a hold on all civilian postal service, so she is unable to send her letter informing Paul that she no longer hates his guts. But she does receive a letter from Paul not long afterwards — dumping her. The death of Paul’s war buddy Etzdorf caused him to do some soul searching, and he concluded that it would be better if he and Hannah split up. Poor Hannah can’t catch a break.

This is very good news for Rudnitzky, though. With Paul out of the way and his good-for-nothing wife finally granting him a divorce (at the price of his beloved music publishing company), there are no longer any obstacles preventing him from getting with Hannah. And yet Hannah still does not return his interest, and this really bums him out.

Some good luck finally comes Hannah’s way. Paul has been injured in combat and is being sent back to Germany to convalesce. He’ll be at the hospital for three weeks — and this time, because he is injured, there is no chance of him being sent back to the front early. He sends a letter to Hannah asking her to come visit him, but Rudnitzky intercepts the letter and hides it. The cycle of agony and ecstasy that Paul has put Hannah through has at last come to an end, and Rudnitzky has no intention of letting Hannah get back on the emotional merry-go-round. Plus, it is the night of the big show — and Hannah might ditch the show for Paul if she read the letter.

Every review of Die große Liebe that you will find makes a big ado about two songs with titles that seem darkly ironic with the benefit of hindsight: “Davon geht die Welt nicht unter”(“It’s Not the End of the World”) and “Ich weiss, es wird einmal ein Wunder geschehen” (“I Know a Miracle Will Happen”). Get it? Because the military miracle Germany needed to win never happened and their world came to an end!

I’m not sure how much I would read into that. When Die große Liebe was released in June 1942, the Axis forces were at their peak in both Europe and the Pacific. When it went into production, the United States hadn’t even entered the war yet. It would have been premature for Nazi propagandists to start talking about miracles at that point. The songs remained popular in Germany throughout the war, and perhaps they took on different meaning in the public imagination later on, but I don’t think the song titles were intended as war metaphors by the filmmakers.

You can buy Son of Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here

In the story, Rudnitzky writes “I Know a Miracle Will Happen,” and the miracle in question is that one day Hannah will love him back. The scene where he composes the tune — alone, at a piano in a bar as it is closing — is one of the film’s highlights.

For Hannah, however, the song is about Paul, and tears well up in her eyes as she sings it. As Rudnitzky watches Hannah sing his love song, he realizes that what Hannah feels for Paul is the same thing he feels for Hannah. Both he and Hannah are in the same boat, and they are both in love triangles. Rudnitzky is in a love triangle with Paul for Hannah, while Hannah is in a love triangle for Paul where the other “woman” is Hitler. Rudnitzky then accepts that while he can’t have his dream, Hannah can still have hers. After the performance, Rudnitzky runs backstage and gives Hannah Paul’s letter. Hannah reads it and announces that she is retiring from music so that she can devote herself to Paul entirely.

As an aside, there is a legend about the above clip that the “female” backup dancers on stage are actually SS officers from the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler SS Division in wigs and dresses. The story goes that when doing large-scale dance numbers, it helps if all the dancers are of the same height so that the choreography looks nice and symmetrical. But Zarah Leander was unusually tall for a woman, and they could not find enough female dancers of similar height, so they used SS officers — who, due to the SS’ height requirements, tended to be of around the same height.

The primary source for this story is Wolfgang Preiss, who played Paul’s war buddy Etzdorf. As he told it:

The Leibstandarte were changing and I came along dressed as an Oberleutnant and the Sergeant Major saw me. “Here comes . . . Achtung!” he shrieked. They all snapped to attention — some in women’s clothes, some with their wigs askew or half made-up, and others in their underpants. It was a grotesque sight.

I don’t know whether this is true or not. But it was not unusual for the Reich to loan soldiers to be used as film extras. A famous example of this was when, in the last year of the war, 20,000 German soldiers were diverted from the front so that they could appear in the battle scenes for the 1945 Napoleonic epic Kolberg.

Paul and Hannah look skyward at the passing fighter planes.

In the final scene, Hannah reunites with Paul at the military hospital. They plan to get married and spend the next three weeks in each other’s blissful company.

“Three weeks. And then?” ask Hannah. Paul directs Hannah’s gaze to the sky, where a squadron of Luftwaffe fighters passes overhead on their way to the front. “Yes?” asks Paul. Hannah silently nods her head, acknowledging that she has passed through all the stages of grief and has arrived at acceptance of her life as a military wife and all that goes along with it. Her character arc now complete, the film ends.

There is a reason why this article is called “The Nazi Casablanca.” There are several reasons, actually. One of them is to turn a review of a movie no one has heard of into clickbait by shoehorning in the name of a beloved classic into the title. But in addition, there are significant parallels between this film and Casablanca when you view both them as propaganda: They essentially have the same message and serve the same propaganda purposes.

The message of Casablanca is not “Nazis are bad.” America was already at war with the Third Reich by the time Casablanca was released, anyway. Rather, the message of Casablanca is, as Bogart says in his famous “We’ll always have Paris” speech, “the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world” — which is essentially the message of Die große Liebe.

On the surface, Die große Liebe and Casablanca might seem to be opposites. The theme of Die große Liebe is holding on, and the theme of Casablanca is letting go. In Casablanca Bogart spends years pining over the one that got away, and when he has the chance to be with her again, he gives her up for the good of the cause. This is in stark contrast to Die große Liebe, which is about a woman standing by her man in the face of a series of heartbreaks and disappointments. But this can be explained by the difference between the American and German experiences in the war.

For Americans, going to war meant that it would be years before you would be able to see your hometown sweetheart again. It’s not reasonable or realistic to expect an unmarried woman to spend an indefinite number of her prime baby-making years waiting for a guy who might not even come back. The guy might die, he might come back crippled, or he might even find some European cutie that he likes better, as did many doughboys during the First World War. Thus, for American men war meant that if you hadn’t gotten around to tying the knot with your sweetheart, chances were not good that she would still be available by the time you got back. (My own grandparents got married a week after Pearl Harbor.)

Convesely, propaganda was needed to make American men feel okay about letting go of their old girlfriends, because if they tried to do the long-distance thing and then got a Dear John letter informing them that sweetheart was now getting the hot dog from ol’ Hank from the milkshake shop around the corner, that would have been bad for morale. So Casablanca ends with Bogart dumping his sweetheart before going off to fight the Nazis. “Where I’m going, you can’t follow. What I’ve got to do, you can’t be any part of” — words many America men were telling their hometown girlfriends.

The German experience of the war was very different. German soldiers were close enough to the front that they could expect to get home leave periodically, and it was good for morale that they could get some sweet lovin’ while there to recharge their proverbial batteries. Thus from the German perspective, the need was for propaganda directed at women with the message that they should hold on. Or, as Zarah Leander says, “He needs someone who’s always there and who is always waiting.”

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Die%20gro%C3%9Fe%20Liebe%3A%0AThe%20Nazi%20Casablanca%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

8 comments

Good review.

Thanks for this review, I will have to find the film online.

Casablanca was certainly intended as propaganda; it may have been released after Pearl Harbor but it was in production long before.

“Although World War II began on September 1, 1939, as late as the beginning of December 1941, the time at which Casablanca is set, most Americans believed that the United States “should stay out of that phony war in Europe.” In fact, a Gallup Poll taken during the first year of the war indicated that an overwhelming ninety-six percent of all Americans wanted the country to remain neutral. However, by the time Casablanca premiered in November 1942, the bombing of Pearl Harbor had already occurred, and the United States had been at war for almost a year. Nevertheless, many Americans continued to support an isolationist foreign policy, and were uneasy about U.S. participation in a war that was thousands of miles away. To counteract this negative public sentiment towards American military participation in WWII, the Department of War established a “War Films” division, and hired filmmakers John Ford, Frank Capra, and Casablanca‘s screenwriters, Julius and Philip Epstein, to travel to Washington, D.C. to create a series of seven American war propaganda films, grouped under the umbrella title of Why We Fight. Warner Brothers also produced some six hundred training and propaganda films under the supervision of Owen Crump, a member of the studio’s shorts department.” — Quoting Frank Miller, Casablanca: As Time Goes By (Atlanta: Turner Publishing, Inc., 1992) https://brightlightsfilm.com/casablanca-romance-propaganda/

Fun Fact: the scene at the end of Barton Fink where studio boss Jack Lipnick appears in an Army uniform “run up for me by the costume department” alludes to Jack Warner (head of Warner’s, natch) who was given the rank of colonel.

Anyway, I remember reading about the UK’s propaganda machine in Hollywood back in the 90s, when Gore Vidal published his Screening Hollywood. Even back then the idea of setting a “fight for freedom” in a French colonial outpost seemed absurdly hypocritical (and it seems to be finally biting the French back today); Renault and company would be merrily torturing Algerian “traitors” in a decade or two. There’s a dialectic here that might be worth exploring but there’s no room for that in a Hollywood film about cartoon Nazzies who are no match for a slug of lead from Rick’s .45.

As it happens, just a few weeks ago I saw someone online observe that “When you realize Casablanca is about three Communists fleeing justice in Europe and planning to set up a new base of operations in New York, it doesn’t seem so romantic.” The problems of two people don’t amount to a hill of beans not because of American “individualism” but because they are obsolete with the inevitable triumph of the Communist system. Well, communism may be gone but largely we live in Victor Laszlo’s world now. “I hope you like what you see” (Brandon in Rope).

I like to think Laszlo would have had himself experimentally frozen during the McCarthy period, and upon revival after the Cold War smirking “Finally those capitalist pigs will pay for their crimes, eh? Eh comrades? Eh?”

By the way, the prototype of one of the main characters in the film Casablanca, Victor Laszlo, was the Czech Jew Otto Katz, one of the most prominent Comintern special propagandists, a man of the school of Willy Münzenberg. He was engaged in anti-fascist propaganda, both truthful and mostly falsified.

But he died at the hands of not the Nazis, but his fellow communists. He was tried under the name André Simone in the Slánský trial, convicted and eventually hanged in the Ruzyně Prison at 3am on 3 December 1952. (That event was described by Yockey in his essay WHAT IS BEHIND THE HANGING OF THE ELEVEN JEWS IN PRAGUE ? published in December 1952).

His body was cremated and his ashes were scattered beside a small road near Prague.

Superb writing, Trav, with important lessons for propaganda today. Great to have you back.

Thanks for the great review. I love reading your reviews of the Third Reich’s films. You’ve got a really detailed study of it. I’d love to do a movie marathon of these films this summer.

Rudnitzky is not a “slav”. He is played by a very popular Austrian-Viennese actor, Paul Hörbiger, a son of Hanns Hörbiger, who created the “World Ice Theory”. Slavic last names are very common in Vienna and other parts of Austria, which does point to slavic descent, but that does not make them “slavs”, and they also were not considered as such in Third Reich.

The firm of Hörbiger still exists.

Goebbels always wanted to have a German “Mrs. Miniver”, but nothing like that was achieved.

Comments are closed.

If you have a Subscriber access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment