Southern writing may be the last American literature in that it has retained a true Anglo-Saxon base in terms of its authors, themes, and relation to history — specifically, white history.

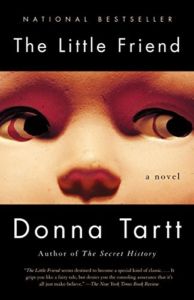

Donna Tartt’s The Little Friend, published in 2015 and winning a justly-earned Pulitzer Prize for best novel, has a real command of writing, and her prose is a roller coaster dipping and rising from sad to exuberant that keeps you reading. I can recall many great phrases such as “The moon shone through a ragged hole in thunderhead clouds,” or “black coins of blood,” “all shining like day-glo Satan,” “a sad dessert from a World War Two ration cookbook,” and “an archivist is just a fancy word for pack rat.”

The novel takes place during the 1970s in Alexandria, Mississippi, and deals with the tragic — indeed, gruesome — hanging of Robin, a four year-old-boy. Coping with his death is a theme throughout the novel, although the family’s pain is sublimated to their own messes and merely coping with life in Alexandria.

Harriet Dufresne is Robin’s younger sister, and she sets out to find the killer. She is bright — a reader, isolated and emotionally crippled by her dysfunctional parents. Her sister Alison proves to be of little help, although she is the only one who may have actually seen what happened.

After a lengthy opening describing the day of the death and introducing the family, especially the collection of aunts who dominate Harriet’s life, an image of Robin strikes and freezes us:

The toes of his limp tennis shoes dangled six inches above the grass. The cat, Weenie, was sprawled barrel-legged on his stomach atop a branch, batting, with a deft, fainting paw, at Robin’s copper-colored hair, which ruffled and glinted in the breeze and which was the only thing about him that was the right color anymore.

This reeled me in, and I couldn’t stop reading.

But The Little Friend isn’t necessarily only a murder mystery, but is also a study of a society, and Harriet’s attempting to come to terms with it from the perspective of prepubescence, isolation, and quiet, introspective rebellion.

The Little Friend is long and clocks in at 624 pages. I was never bored , but Tartt spends a lot of time on description — six pages on something, anything, where two pages would have done. But her prose always captivates.

Tartt depicts Alexandria through the worlds of two families: Harriet’s family, the Cleves (perhaps a parody of the Cleavers from Leave It to Beaver?); and the Ratliffs, a poor white family of dysfunctional, wild, and dangerous people. Harriet concludes that Danny, one of the Ratliff brothers, killed Robin. Without any actual evidence, she begins a solitary crusade aided by Hely, a younger boy who is semi-competent at best. He adores her, although she doesn’t adore him, and as helpful as he tries to be, their relationship reminds me less of Holmes and Watson than Gilligan and the Skipper.

Hely means well, but has the usual adolescent distractions. If Harriet needs him for a quick moment to solve the mystery, he’s usually caught up in band camp, idolizing the cool trombone section. He’s very much an early adolescent, and Tartt captures his mind wonderfully.

The same is true of Harriet. She has a child-like obsession with finding her brother’s killer, but it is often more emotional than wise. Although Tartt credits Sherlock Holmes and Houdini as guides in writing The Little Friend, there’s very little in terms of deduction or clever escapes in Harriet’s actions. She comes off as someone whose isolation and vociferous reading make her cook up ideas and deductions.

Wanting to escape the reality of Alexandria and her family is understandable, of course. Charlotte, her mother, is a mental wreck, still grieving over Robin’s death. Dix, her father, left for Nashville, and is barely mentioned. Alison is uncommunicative and sleeps a lot.

The family is defined by the grandmothers and aunts who circle Harriet: Tat, Edith, and Adelaide, Their lives, a mixture of women’s pettiness and pleasure, is one of the novel’s major selling points. Tartt captures this small-town life of older women splendidly. It recalls my world, where I grew up with three older, single women around me and a semi-dysfunctional mother. Every nuance — from tabletop gossip, sibling bickering undeterred by age, and coping with life and aging, all the while sublimating Robin’s loss — is powerful in this well-depicted universe.

I found myself liking the older women far more than Harriet. She is defined as a well-rounded character, which she is, but she’s not a likable one. Harriet is sullen, sarcastic, rude, withdrawn, and not a very pleasant pre-teen to be around. I don’t say this as a criticism; it’s simply an observation. Jim Kunstler, a writer I know, warned writers not to depict their heroes negatively; making them unlikable turns the reader off. Harriet is definitely unlikeable, but her strength and determination is the plot’s prime force. She has a lot of weight on her shoulders, and I never found her boring or disinteresting. If there are two things I remember liking about her, it is when she insists that Weenie, the family cat, be allowed to die with dignity; and when a girl, trespassing in their yard, drops a library book after Ida, the maid, chases her and her brothers away. Ida rants about “white trash kids” in the yard, and tosses the book in the garbage. Harriet protests, but Ida shoots back that if white trash carries a book, that, too, is trash. Into the rubbish it goes, and stays.

You can buy Tito Perdue’s The Smut Book here.

But Harriet, out of Ida’s eye, retrieves the book, cleans the coffee grounds off, and returns it to the library. So she’s not totally unlikable.

In a Southern novel, race inevitably enters the scene, but The Little Friend only depicts it in terms of Ida and Odom, two black maids, one of whom works for Harriet’s aunts and the other for Charlotte. They lack the folksy wisdom and profundity of many noble negroes in modern literature. Ida and Odom do their work, but they’re grumpy and less than impressed with whites, especially the hapless Charlotte. They feel they’re underpaid and not shy about saying it. When they are dismissed, they readily move on to something else. Ida’s loss devastates Harriet and Eileen, but it does provide Charlotte with a wake-up call to get her house (literally) in order. Tartt seems almost to imply that blacks are a burden to whites because they keep them from doing what they should be doing themselves. The racial melodramatics of the usual Southern novel are absent here.

I think much of The Little Friend is derivative, and it made me recall Carson McCuller’s The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, The Member of the Wedding, bits of William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams, and, inevitably, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird.

Harriet certainly owes a lot to Mick Kelly and Frankie Adams of McCuller’s works. It’s interesting that Harriet even wears the same short, straight black hair that these characters do, as well as Scout in Mockingbird. Even more interesting is that in her book jacket photo, Tartt has the same severe but not unbecoming hairstyle, her eyes directly focused on us like a southern gothic Antigone).

I don’t consider these comparisons to be slights against Tartt’s art; she is safely in the tradition of Southern literature, but is very much her own voice. Again, when I read about the world of Alexandria, I was back in my own small town in southeast Missouri — a semi-Dixie.

The streets, the languid dullness of summer, the smells of wild grass, the flowers, the rusting abandoned places, the odors of kitchens and older women, and a serenity that envelops one — it is the cocoon of Baptist life, from sermons to church camp, and all are well-described.

The Ratliffs, by contrast, are white trash felons and ne’er-do-wells. I felt they were stereotypes to a greater degree than the Cleves. There is the brutal, semi-insane Farish; his brothers Eugene and Danny; and Gum, their long-suffering mother. As they are into violence and drugs, perhaps the Ratliffs are a depiction of the new South, falling into methamphetamine and paranoia partly from dope and male dominance. Tartt makes what I think is a snide comment that might betray her liberalism when she describes the Ratliff children as looking dull and moronic, with the looks of homeschooled children. Really, Donna? Homeschooled children are almost always exceptional and better-educated than the usual crop of public school sheep. I knew two homeschooled girls who received college scholarships. I sense that Tartt uses the Ratliffs to allow her resentment of working-class Southerners to come through — perhaps to establish her credibility with the New York literary world.

Eugene has very extreme religious views involving handling poisonous snakes while preaching. A roomful of snakes plays a very important part of the plot in a simultaneously gruesome, gothic, and farcical mix that will make you laugh and cringe at the same time. Getting a snake is one of Harriet’s goals. She and Hely, her bemused and shocked confederate, steal one in order to kill off a Ratliff by dropping it on him as he drives under an overpass. It’s a mix of farce and creepiness, with true Gilligan’s Island results. While exciting, it made me wonder how sympathetic it makes Harriet. Mick, Frankie, and Scout would never have done that.

I found the snake-handling section rather grotesque, recalling a 60 Minutes segment on the subject, which discussed how deeply they became embedded in Southern fundamentalism. I felt it was far too sensational a depiction of the South, but I admit it made for an excellent plot point.

I noted how weak the male characters are compared to the female ones, however. From the hapless Hely to drug-addled Danny, men here come across as rather unpleasant. Roy Dial, the local Baptist businessman, is a positive depiction of a Christian businessman who is determined to live a good, moral life while owning property, selling cars, and reluctantly renting an apartment to a pair of Mormons who have deserted their church. Roy flatly offers a bus to the Cleve sisters for their long-anticipated journey to Charleston, but charges them for the gas, and this leads to a sisterly crusade against Roy’s piety that coexists with his making a buck. He’s a kind of Babbitt, and never dull.

I’m not quite sure the weakened male characters are a detriment, however. I think that Tartt, like Jane Austen, simply doesn’t have the same level of interest in her male characters as the female ones.

Tartt doesn’t have a great deal of interest in telling a straightforward narrative. She lingers. There are many exceptional passages, but at times I wish she would get to the point. This also extends to the end of the story, as there is no decisive end or climax.

Harriet, now being tracked by the Ratliffs, climbs an abandoned water tower, ostensibly to escape from them, but it also offers a strong thematic study of her isolation. The tower, rusted, abandoned, and rotting away in a sense that will aid the plot, is another of Tartt’s incisive descriptions of small-town America, decayed and abandoned. But as Harriet pauses to look out, there is a mild epiphany in the following brilliant description that leaves you hypnotized:

The view had captivated her; wash fluttering on lines, peaked roofs like a field of origami arks, roofs red and green and black and silver, roofs of shingle and copper and tin, spread out below them in the airy dreamy distance. It was like seeing into another country. The vista had a whimsical, toy quality which reminded her of pictures she’d seen of the Orient-of China, of Japan. Beyond crawled the river, its yellow surface wrinkled and glinting, and the distances seemed so vast it was easy to believe that a glittering clockwork Asia lay hammering and humming and clanging its million miniature bells just beyond the horizon, past the river’s muddy dragon-coils.

It’s clear that Alexandria is dull. It isn’t a bad place, but it’s not Harriet’s place. She wants to escape, yet is determined to solve the mystery of Robin’s death. The landscape is dreamy, offering visions and hope. I especially liked that dragon-coiled river — a thematic bit blending in with the snakes. It’s also symbolic that Harriet, like the doomed Robin, rises above the ground, he on a noose and she scaling the rotting, graffiti-scarred, and stinking tower.

The Ratliffs find her. A confrontation follows, but it leads to a dead end. Everything that follows is an anti-climax,. The story ends not on a stern, strong Harriet, but on the kind but hapless Hely and his family. This could be frustrating for some, but for me it was a a laugh out loud moment — a kind of satyr play to bring us down from the tragic drama that has been Harriet’s quest.

I don’t fault Tartt. There is an entire genre of literature that eschews the convention of a “happy” ending, or even a coherent one. Nothing is resolved, and life simply goes on. There is a hint at the end of the story that Harriet may go with Charlotte to Nashville, as Dix appears and mutters here and there about returning to fatherhood. Charlotte, for her part, has cleaned up her act somewhat. She was an incoherent mess before, a mother bird dulled by the loss of her fledgling. Now, cleaning the apartment and forcing a smile, she is merely annoying. But we must wonder, as does Harriet, where life will take her.

It seems to me that Nashville can’t be anything but a step up. For starters, it has more libraries.

The ending recalled that of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. After Mick’s setback, we end with an almost despairing slice of life with Biff Brannon offering a moody monologue. At least Tartt leaves us smiling.

Like Salinger, she captures young people’s intensity and isolation very well — their frustration and the battle all adolescents are fighting between emotion and reason, hoping to find answers to the problems, both personal and communal, that they are enmeshed in.

Donna Tartt may well be the Mississippi Tolstoy . . . with snakes. Lots of snakes.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

The%20Little%20Friend%3A%0AA%20Southern%20Epic%2C%20Tartt%20andamp%3B%20Spicy%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Mechanisms of Information Distribution

-

Overturning Roe v. Wade

-

When The Temperate Is Decried as Extreme: A Review of When Harry Became Sally: Responding to the Transgender Moment

-

Widow Clicquot: The Napoleon of Wine

-

A Nice Place To Visit: Lovecraft As The Original Midnight Rambler, Part 4

-

Prepping for Kids

-

Pass It On: Vladimir Volkoff’s La Grenade

-

A Nice Place To Visit: Lovecraft As The Original Midnight Rambler, part 3

7 comments

I look forward to reading this eventually, as I, too, enjoyed this novel. Actually, I enjoyed all three of Tartt’s novels, though each left me wondering: was this literature, or merely well-written fiction (and if the latter, which genre: drama or thriller?)? I still can’t decide.

What I do know, however, and this without even Googling, is that Tartt won the Pulitzer for The Goldfinch, and that The Little Friend was published about two decades ago (I read it in the 00s).

Thanks for that great review. You’ve stoked me to read Tartt, but I think I’ll start with secret history bc it’s shorter. I’m a slow reader.

I agree that home schooled kids are usually far above school schooled ones. I’m from roughly the same part of the country and cultural milieu as Tartt, and I’ve met numerous impressive young people who were home schooled. The actually bad are the “skoo” schooled ones. They have that dull and violent look!

Great to hear about a piece of modern southern literature that is more in the tradition of Faulkner than the current “muh segregation” trope that has infected every single piece of writing about the South. Putting this on my to-read list and bumping it to the top. Hail Dixie!

Good Lord! She didn’t win the Pulitzer for this! She won it for The Goldfinch.

Not good.

JC: Got me there, my apologies. The Little Friend did win the WH Smith Literary Award, and was nominated for the Orange Prize in fiction in 2003.

My review of the REAL Pulitzer winner, The Goldfinch, will be up soon. Watch for it, and keep checking me for bloopers. To paraphrase Nietzsche, if it doesn’t make me look completely stupid, it only makes me stronger.

An impressive response! Good for you, and for your readers.

?????

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment