A Nice Place to Visit

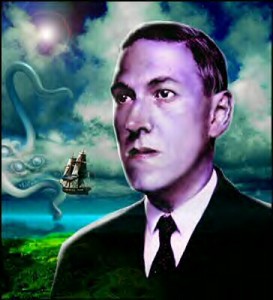

Lovecraft as the Original Midnight Rambler

James J. O'Meara

4,817 words

David J. Goodwin

Midnight Rambles: H. P. Lovecraft In Gotham

Fordham University Press, 2023

Part 4 (Read Part 1 here. Read Part 2 here. Read Part 3 here.)

Awakened Cthulhu, Woke Lovecraft?

There are several places where Lovecraft seems to step out of character, or at least displays views that conflict with his image as a man of the Right.

Lovecraft’s hatred of New York was tempered, and for a brief period overcome, by his sense that as a man of letters, a large metropolis had much to offer. Here, Lovecraft reflects on his surroundings during a trip to Cleveland:

After a night in the sleeping car, Lovecraft watched the passing Pennsylvania and Ohio countryside washed in the morning light from his train seat. Compared to his beloved New England, the scenery was underwhelming, and he ranked the flat Midwestern landscape as “inferior” and the region’s towns and villages as “insufferably dismal—like ‘Main St.’” This reference to Sinclair Lewis’s 1920 novel Main Street, a critique of self-satisfied small-town American life, is telling. Lovecraft’s distaste for “the real America” displayed another contradiction in his intellectual character. Although his nativist beliefs largely resembled those dominant in middle America, he did not align himself with its largely anti-urban, antiintellectual, and moralistic values. Reflecting on his physical view from the train, Lovecraft declared, “I was glad that my destination was a large city!”

Overall, Lovecraft found Cleveland to be a revelatory, successful, and uplifting adventure. Much as he had during his spring sojourn in Brooklyn, he experienced belonging to a true intellectual and literary circle. He began to gradually realize that this might be impossible in his native Providence, where he derided art and culture as “confined to artificial” and “quasi-Victorian society groups.” Maybe for the first time, Lovecraft desired a different life for himself, one away from his family and well-worn patterns. Traveling to Boston, New York, and now Cleveland to socialize with fellow creative individuals freed him to imagine the possibilities. When he finally left Ohio on the early morning of August 16, he did not board a train to Providence. Instead, he returned to New York and Sonia Greene.

Just as, being a native Michigander, I bristle at the Great Lakes Region being lumped in with those corn-fed hicks of the Midwest flatlands, I wouldn’t call this a “contradiction” so much as a paradox. Lovecraft would not be the first or only figure on the Dissident Right, or even the conventional Right, who needed to balance taking the side of the “real America” and desiring or needing to live somewhere else.

The only trouble with Providence is its inhabitants—backward & unimaginative bourgeois types who go to church, revere the gods of commerce & the commonplace, & find their utmost limit of aesthetic & intellectual expansion in mock art-clubs & tame lectures wherein gossip of the day & social pageantry form the real motive forces. [1] Estimable Philistines —worthy folk—correct & solid citizenry—but still living in the anaesthetic [sic] eighties of the nineteenth century.

While Houellebecq is correct to say that New York “helped him” it was largely through evoking his disgust during a temporary sojourn – he would never refer to it in later life than as living in “the pest zone” – and there is no hypocrisy in a return to nowhere but Providence for a man who announced that “I am Providence.”[2]

A couple more inconsistencies deserve note. Visiting Coney Island on a night mercifully free of the immigrant and lower-class scum Lovecraft abhorred, he was fascinated by “an aging performer dressed in a tuxedo and playing a violin and xylophone for the show’s guests…. This was ‘Zip, the Pinhead,’ otherwise known as ‘The What-Is- It.’”[3]

Given the range of acts at Coney Island, why did “Zip” draw Lovecraft’s attention? [And] as someone who instinctively disparaged ethnic and racial minorities, he refrained from making similar comments concerning this seriously disabled individual.

And indeed, apart from being “someone who instinctively disparaged ethnic and racial minorities,” he was also an artist who specialized in the creation of the weird and terrifying.

He did not seem to be unnerved or disgusted by Zip’s abnormalities or question the validity of his or his fellow (and presumably equally physically challenged) performers’ social place on Coney Island and within the city beyond the beach.

In the margins of his letter chronicling his and Greene’s night at the beach resort, he drew a sketch of the performer’s head. Lovecraft himself had a long face and high forehead. Prior to his marriage, he was deeply insecure about his facial features. When he was a child and later a young man, Lovecraft’s mother may have tormented him about his looks. A neighbor recalled Sarah Susan Lovecraft describing her son as “awful” and “hideous” and her near obsession with his physical appearance. She seemingly failed to observe that her son inherited her own facial characteristics. Greene herself remembered Lovecraft’s acute complexes about his looks early in their relationship. Subconsciously, might have the imprint of possible emotional abuse and trauma resulted in a quiet empathy for Zip on Lovecraft’s part?

Well, that certainly seems a reasonable conjecture. One might also consider this anecdote, which Goodwin buries in the endnotes and draws no explicit lesson from:

This empathy toward the disabled appeared again in Lovecraft’s life. While traveling through Washington, D.C., in May 1929, he made a point to visit poet Elizabeth Toldridge (1861– 1940). She suffered from an unspecified disability and was confined to her apartment. The limited evidence of Lovecraft’s view of the disabled contrasted with the then dominant public perception of such individuals. [4]

If here disability was “unspecified” his empathy must have been aroused by her general, housebound situation, and so again, like his body dysmorphia and the Coney Island “freaks,” Lovecraft clearly empathized with someone suffering from a similar condition to his own: in this case, his years, before and after this period, living essentially as a hermit, communicating with the world only through his writing.

We can infer that Lovecraft’s views on non-Whites and immigrants prompted the extreme and inflammatory expressions that Goodwin deplores – just after visiting Zip, Lovecraft has a silhouette made of Greene by a famous Coney Island performer he refers to as “that smart nigger” – because of his inability to fully empathize with such outsiders. Nor did he feel threatened by them taking over his beloved New England. So we can also infer that however much they might agree on some issues, Lovecraft would not be fully onboard with such “edgelords” who find the deformed or “crippled” to be readymade for memes and mockery.

But What About the Stories!

Despite being unemployed, and a neglectful husband, Lovecraft did almost no writing, other than keeping up his legendary correspondence and, eventually, a diary, preferring to spend his time meeting up with “the gang” or going on group or solo rambles; if he was living “like a college student” he was one with very bad study habits.

However, a spending all day in the “fantastic Eden” of Prospect Park, a surge of creative energy produced the first of his New York stories, “The Horror at Red Hook.”

Alas, it’s not much of a story. It’s over-written, in the way that Lovecraft would be, fairly or unfairly, accused of (and which he had already successfully parodied in “The Hound”), and the plot is basically just the usual pulp horror melodrama, with some occult nonsense literally copied from the Encyclopedia Britanica.

It’s interesting as an attempt perhaps break into the new “detective” genre: the protagonist, rather than being the usual Lovecraft stand-in, is a tall, powerfully built police detective — an Irish immigrant, no less! – though neither his physique nor his peasant heritage prevent him from suffering the usual mental breakdown upon witnessing eldritch horror. And Lovecraft now for the first time makes use of the New York lore and atmos he’s picked up on his rambles: the Flatbush history, the Suydam family name, the Dutch Reformed Church and cemetery,[5] and above all, the crumbling wreck of the Red Hook neighborhood, just a few blocks from Lovecraft’s apartment.

He investigated the neighborhood on at least one occasion in March 1925, detecting “an evil hush” draped over “the entire sprawling fester” and “a hideous element” metastasizing throughout the area. Always acutely aware of the built environment, he noted that this phenomenon spread across the varied architecture of the waterfront streets. Both “crumbling mansions” and “dingy frame tenements” were equally afflicted. In his estimation, the rot of immigrants had poisoned much of this swath of Brooklyn. Nearby Gowanus presented a consoling contrast: it “resisted the foreigner” and thus retained a rugged “pride and self-respect.”[6] Looking past Red Hook’s “wild squalor,”

Lovecraft could not help but admire some of its modest brick homes. A tarnished beauty managed to shine through the neighborhood’s perceived decay.[7]

And there’s the problem, for the “modern” reader: while Sonia recalls that the story “was inspired by Lovecraft’s unpleasant observation of ‘rough, rowdyish men’ at a Brooklyn restaurant where the couple was dining with friends,” by the time he sat down to write it, in the course of two days, they had become “the nameless ‘slant-eyed’ cultists and ‘squinting Orientals,’ mainly Kurdish and Yazidi immigrants” who “are engaged in human-trafficking, bootlegging, smuggling, child-kidnapping, and human sacrifice.”

“The Horror at Red Hook” uniformly ranks as Lovecraft’s most problematic piece of fiction, and it represents his raw reaction to a city becoming unpalatable to his sensibilities. He summarized it as “my brief hymn of hate.”

As usual, though, your mileage may differ. Once more, was Lovecraft a barely restrained ultra-bigot, or no less than a prophet? Rat-faced immigrants, digging a secret network of tunnels connected to a blasphemous church, engaging in child sacrifice and human trafficking? In Brooklyn? That could never happen. Or how about “Vicious, swarthy foreigners speaking harsh, strange-sounding tongues prey upon blue-eyed, innocent children”?

The next New York story, “He,” emerged only a couple days later – after an epic all-night ramble, from Greenwich Village down to the Battery and then by ferry to Elizabeth, N.J, where he bought a notebook at 7AM to begin his new story — and is a whole other kettle of Dagon. Its famous opening paragraphs express Lovecraft’s own evaluation of his existential situation in restrained yet powerful rhetoric:

I saw him on a sleepless night when I was walking desperately to save my soul and my vision. My coming to New York had been a mistake; for whereas I had looked for poignant wonder and inspiration in the teeming labyrinths of ancient streets that twist endlessly from forgotten courts and squares and waterfronts to courts and squares and waterfronts equally forgotten, and in the Cyclopean modern towers and pinnacles that rise blackly Babylonian under waning moons, I had found instead only a sense of horror and oppression which threatened to master, paralyse, and annihilate me.

The disillusion had been gradual. Coming for the first time upon the town, I had seen it in the sunset from a bridge, majestic above its waters, its incredible peaks and pyramids rising flower-like and delicate from pools of violet mist to play with the flaming golden clouds and the first stars of evening…. [8]

But success and happiness were not to be. Garish daylight shewed only squalor and alienage and the noxious elephantiasis of climbing, spreading stone where the moon had hinted of loveliness and elder magic; and the throngs of people that seethed through the flume-like streets were squat, swarthy strangers with hardened faces and narrow eyes, shrewd strangers without dreams and without kinship to the scenes about them, who could never mean aught to a blue-eyed man of the old folk, with the love of fair green lanes and white New England village steeples in his heart.

Not only is the narrator Lovecraft, the Midnight Rambler, himself, but “the narrator’s meeting of the eccentric stranger resembled Lovecraft’s own interaction with a wizened and eloquent figure while exploring Milligan Place with Sonia Greene in August 1924.”

That elderly “gentleman of leisure” talked about the history of the courtyard community with the couple and cheerfully provided them with a private introduction to it. Lovecraft likely recalled this winding tour of Milligan Place and its secret nooks when he described the narrator of “He” silently trailing the stranger through an “inexhaustible maze of unknown antiquity.”

Of course, Lovecraft invented the part about passages so cramped they had to crawl on their hands and knees, along with the old man’s tale of misappropriating Native American rituals. Goodwin makes an interesting point about their destination:

The manor house of the stranger appears to be an interstitial portal or liminal zone physically linked with the colonial era romanticized by the narrator as a time far more elegant, artful, and humanistic than his own present age. Much to his shock, this supernatural bridge to the past unleashes just as much—if not greater—danger as the contemporary city that he has come to abhor. New York offers no safety or solace.

Unlike the previous tale, the occult elements seem more authentic – we even get what might pass as a bit of Neville:

“… all the world is but the smoke of our intellects; past the bidding of the vulgar, but by the wise to be puffed out and drawn in like any cloud of prime Virginia tobacco. What we want, we may make about us; and what we don’t want, we may sweep away. I won’t say that all this is wholly true in body, but ’tis sufficient true to furnish a very pretty spectacle now and then.

Alas, as the dénouement approaches, Lovecraft once more can’t resist his pulp instincts, but at least the revenge of the “sartain half-breed red Indians” is saved for the end. Still, without it we would end with another splendid bit of prose, combining high fantasy with race realism as only Lovecraft can:

I saw a vista which will ever afterward torment me in dreams. I saw the heavens verminous with strange flying things, and beneath them a hellish black city of giant stone terraces with impious pyramids flung savagely to the moon, and devil-lights burning from unnumbered windows. And swarming loathsomely on aërial galleries I saw the yellow, squint-eyed people of that city, robed horribly in orange and red, and dancing insanely to the pounding of fevered kettle-drums, the clatter of obscene crotala, and the maniacal moaning of muted horns whose ceaseless dirges rose and fell undulantly like the waves of an unhallowed ocean of bitumen.

I saw this vista, I say, and heard as with the mind’s ear the blasphemous domdaniel of cacophony which companioned it. It was the shrieking fulfilment of all the horror which that corpse-city had ever stirred in my soul, and forgetting every injunction to silence I screamed and screamed and screamed as my nerves gave way and the walls quivered about me.

Those “yellow, squint-eyed” people (or vermin) are presumably the descendants of the “squat, swarthy strangers” that annoy the narrator in the present; the city is already a corpse:

[T]his city of stone and stridor is not a sentient perpetuation of Old New York as London is of Old London and Paris of Old Paris, but that it is in fact quite dead, its sprawling body imperfectly embalmed and infested with queer animate things which have nothing to do with it as it was in life.

Joshi tut-tuts about Lovecraft’s “sophism” that these immigrants “really have no kinship” with a city founded by the Dutch and English since they are “of a different cultural heritage altogether.”[9] Looking at London and Paris today, can we not once again saw that Lovecraft was a prophet?

The very next night, Lovecraft received the first stirrings in his imagination of what would become his greatest tale, “The Call of Cthulhu.” Despite beginning to take shape (or shapelessness) in Gotham, it would not be brought into our dimension until, significantly enough, Lovecraft had forsaken New York City for Providence.

Instead, there would be a final New York Story, “Cool Air,” which Joshi calls “a compact exposition of pure physical loathsomeness,” [10] and also draws on details of his urban experience; the setting was based on his friend George Kirk’s apartment/bookstore at 317 West 14th Street (Lovecraft mocked the building as “the Hotel Hispano-Americano” and indeed today it’s the Chelsea Pines Hotel), while the “slatternly, almost bearded Spanish woman named Herrero” who runs it seems like Lovecraft’s revenge on his current landlady.

Goodman makes an interesting point about “the story’s two central characters, the unnamed narrator and Dr. Muñoz”; while in “He” Lovecraft draws on his encounter with the amateur guide in Greenwich Village, here we have “dual images of Lovecraft’s conception of himself, specifically during his latter time in New York.”[11]

The narrator is a man of letters, failing to earn a viable income as a magazine writer in the city and forced to inhabit quarters much below his self-declared social standing. He views his period in the building as a stasis or hibernation “till one might really live again.” While writing “Cool Air,” Lovecraft held a similar estimation of his relationship with New York and his own life.

The high-born, cultivated, and educated Muñoz, a man of “striking intelligence and superior blood and breeding,” resembled Lovecraft’s own carefully crafted identity as the scion of shabby Yankee gentry once destined for far greater things. With his keen attention to furnishings and art, Muñoz constructed a sanctuary from the rabble and commotion of the modern city. Lovecraft created a similar physical and mental refuge in his Brooklyn Heights room. He even inserted a telling feature of his own home into his description of that of Muñoz: both men slept on a folding couch to maximize space and maintain the aura of “a gentleman’s study.” Muñoz’s bodily need for low and eventually freezing temperatures conversely mirrored Lovecraft’s own dislike of the cold and his insistence on high heat.

A Nice Place to Visit, But…

CIA Superior: What did we learn, Palmer?

CIA Officer: I don’t know, sir.

CIA Superior: I don’t fuckin’ know either. I guess we learned not to do it again.

CIA Officer: Yes, sir. [12]

But what of the mystery of Lovecraft himself, the mystery of why he married Sonia Greene and moved to New York. I think we have enough material to put together a likely hypothesis.

When Lovecraft met Greene, he must have realized, at some perhaps deeply buried level of his unconscious – or through his powerful imagination – that welcoming her advances would solve a number of major problems.

While Lovecraft was not opposed to marriage as an institution – even as an atheist and materialist, he insisted on a socially proper wedding ceremony, as part of the social tradition he felt at home in – he was, shall we say, rather diffident about the whole man/woman thing, like any stereotypical WASP gentleman (such as he pretended to be). Nevertheless, becoming a married man would regularize his life, give him a place in the social structure and – of course – provide him with someone to handle all the domestic chores, including his travel, moving and publication arrangements, as his late mother and later his aunts did, as well as access to more money to support his “respectable” and “aesthetic” lifestyle – we’ve seen that Sonia handled and paid for nearly every aspect of their domestic life, along with his social gallivanting.

It’s something that we’ve seen in nearly every novel from the 18th century until the postwar “liberation” period. Of course, Lovecraft’s blithe continuation of what Goodwin calls his “bachelor lifestyle” makes him somewhat of a 18th century cad, or oddly enough, what we might call a “chad” today.

But the more likely explanation is the typically autistic way in which Lovecraft lived in his imagination: why tell anyone that he’s decided to get married and move to New York, after the decision becomes firm in his mind; it’s as good as done, just as walking along an old colonial courtyard is “just like” being in the 17th century. [13]

As for married life, all that “two as one” rubbish was never considered: “He’s with his friends!”[14]

Lovecraft was opposed to Jews, immigrants, Modernists and New York City. But again, we’ve seen how Lovecraft was able to “compartmentalize” his relations with others, such as Samuel Loveman. He could well have boasted that “some of my best friends are Hebrews!”

As for New York City, home of both Jewry and Modernity, we’ve seen how Lovecraft used his powerful imagination to seek out and live among the remnants of colonial New York still extant in the megalopolis. As we also saw, he rejected the idea of editing Weird Tales, ideal though the job might have seemed, since it would entail moving to Chicago, a purely Modern city that he instinctively loathed.

In the end, none of this really worked out. And yet it accomplished what may have been his real goal, perhaps unknown even to himself: to mature as a writer. His encounters with Jews, Negroes, immigrants, and Modernity triggered increasingly violent loathing, that could not be compensated for by the reconstructed New Amsterdam he imagined around himself. Moreover, he even came to appreciate the need to step out of provincial Providence, if only relatively briefly, to both polish his craft among fellow artists, and appreciate, if only by contrast, where the wellsprings of his creativity did ultimately lie.[15]

Although he ultimately realized that as a person and an author he could not function outside of Providence, this conscious appreciation of his environment was made possible by the years spent among the Others.

Regardless of his distaste for New York and his dissatisfaction living there, it provided him with the physical separation and mental distance necessary for him to mature as a writer. If he had not boarded a Manhattan-bound train in March 1924, he might never have fashioned his unique and disturbing literary vision. Lovecraft enjoyed his most prolific creative period after returning to Providence, authoring all his ‘great texts’ between 1926 and 1935.

When he left New York, he was already percolating his first great tale, “The Call of Cthulhu,” and as his home town came into sight he whooped “I am Providence!”

Notes

[1] Lovecraft here anticipates Hesse’s remarks in The Glass Bead Game on “the age of the Feuilleton” as the 25th century narrator characterizes our own time: Mark Gullick calls it “a time of light, engaging literature with no intellectual sustenance, and a sardonic foreshadowing of our own times.” In these popular lectures and newspaper filler, “Noted chemists or piano virtuosos would be queried about politics, for example, or popular actors, dancers, gymnasts, aviators, or even poets would be drawn out on the benefits and drawbacks of being a bachelor, or on the presumptive causes of financial crises, and so on. All that mattered in these pieces was to link a well-known name with a subject of current topical interest.” See Mark Gullick, “Higher Education: Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game.”

[2] Even Burroughs – in the “Post Script of the Regulator” to Agent Lee’s call for “total resistance” to the Nova Criminals – felt the need to “sound a word of warning – To speak is to lie – To live is to collaborate – Anybody is a coward when faced by the nova ovens – There are degrees of lying collaboration and cowardice.” (Nova Express, “Last Words”). After time in New Orleans, New York City, Mexico City and Tangiers, Burroughs himself wound up puttering around in Lawrence, Kansas, where he could shoot guns and collect cats; biographers always point out that it’s a “college town” and had a thriving punk scene.

[3] “A Black American born in New Jersey to formerly enslaved parents, William Henry Johnson, “Zip,” suffered from microcephaly. He shaved off his hair except for a small tuft to draw attention to his extended jaw, tapered cranium, and small head. By 1925, he was a longtime veteran of circuses and sideshows, having performed at Barnum’s American Museum and the Ringling Brothers Circus. While touring the United States between December 1867 and April 1868, novelist Charles Dickens purportedly saw Johnson at Barnum’s and exclaimed, “What is it?” According to this legend, the author of David Copperfield and Great Expectations unknowingly had bestowed a permanent stage name upon Johnson.”

[4] Goodwin adds that “In fact, medical, legal, and educational professionals collectively questioned if disabled people were fully competent to act as full citizens, and little thought was given to the disabled in public space and life at that time in America.” He provides no documentation for this claim, although I suppose it is true in a milder sense. A few years after this Franklin Roosevelt’s disability would be carefully hidden from the public, but it was obvious to anyone who was around him, and I doubt anyone ever tried to have him removed as not “fully competent.”

[5] Lovecraft had visited the cemetery and, remarkable for a supposed antiquarian, vandalized a tombstone by chipping off a souvenir; again, reminding us of “The Hound,” or perhaps The Blair Witch Project.

[6] Again, Lovecraft sees what he wants to see: “The Gowanus Canal, located in Brooklyn, NY is one of the most heavily contaminated water bodies in the nation. This 1.8 mile long, 100 foot wide, canal was built in the 19th century and historically was home to many industries including manufactured gas plants, cement factories, oil refineries, tanneries, and chemical plants. After nearly 150 years of use, the canal has become heavily contaminated with PCBs, heavy metals, pesticides, volatile organic compounds, sewage solids from combined sewer overflows, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).”

[7] Readers might only know Red Hook from the book or movie Last Exit to Brooklyn, which shows what a sinkhole of scum and villainy it remained into the late ‘50s. Despite living many years in New York, I only ventured into Red Hook once: appropriately enough, for a Psychic TV concert.

[8] Compare, from another, later work of disillusionment: “The city seen from the Queensboro Bridge is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and the beauty in the world.” — The Great Gatsby.

[9] Op. cit., p.796.

[10] Op. cit., p.821. Joshi thinks this is the best New York story, even as an attempt at invoking horror from the noisy, teeming modern metropolis, and “some of the gruesome touches are uncommonly fine.” He also finds “a deliberate undercurrent of the comic,” as when Dr. Munoz is hiding in the bathroom, in a tub full of ice, shouting “More!” (p.828). The latter scene reminds me of Dr. Gonzo in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, sitting in a bathtub filled with green bath salts, splashing around with a hunting knife and demanding that Thompson throw a cassette player in with him: “Music! Turn it up!” See Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream (New York: Random House, 1972), pp.58-62.

[11] Some have suggested that the old man encountered by the narrator in “He” is his own (and thus Lovecraft’s) past self: “’You behold, Sir,’ my host began, ‘a man of very eccentrical habits, for whose costume no apology need be offered to one with your wit and inclinations. Reflecting upon better times, I have not scrupled to ascertain their ways and adopt their dress and manners; an indulgence which offends none if practiced without ostentation…. I believe I may rely on my judgment of men enough to have no distrust of either your interest or your fidelity.’”

[12] Burn After Reading (Coen Bros., 2008)

[13] You’re talking a lot, but you’re not saying anything, When I have nothing to say, my lips are sealed, Say something once, why say it again? – David Byrne, “Psycho Killer.”

[14] A perennial problem with mixed marriages; from Goodfellas:

He didn’t call?

He’s with his friends.

What kind of person doesn’t call?

He’s a grown-up. He doesn’t have to call every five minutes.

A grown-up would get you an apartment.

Don’t start. Mom, you’re the one who wanted us here.

You’re here a month and sometimes I know he doesn’t come home at all. What kind of people are these?

What do you want me to do?

What can you do? He’s not Jewish. Did you know what these people were like? Your father never stayed out all night without calling.

Daddy never went out at all, Ma! Keep out of it! You don’t know how I feel!

How do you feel now? You don’t know where he is or who he’s with!

He’s with his friends! Dad!

Leave him alone. He’s suffered enough. He hasn’t digested a decent meal in six weeks. [Shades of Lovecraft!]

[15] “Man’s task in the world is to remember with his conscious mind what was knowledge before the advent of consciousness.”— Erich Neumann, The Origins and History of Consciousness (Princeton, 1973) p. 24

A%20Nice%20Place%20to%20Visit%0ALovecraft%20as%20the%20Original%20Midnight%20Rambler%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

What minds what we matter?

-

When Harry Became Sally

-

A White Nationalist Novel from 1902 Thomas Dixon’s The Leopard’s Spots

-

A French View of the Empire of Nothing in 2002

-

Thug – Or a Million Murders

-

Society vs. the Market: Alain de Benoist’s Case Against Liberalism

-

Critical Pedagogy

-

An Idea Whose Time Has Come

5 comments

I feel a sadness for Lovecraft. I can tell by his writings he was a very intelligent man. I’ve really enjoyed listening to his books on audio. I don’t think people realize just how much of an impact he’s had on science fiction writing and actually literature in general. I mean he basically made the cosmic horror genre. Had his mother loved him more he may as well turned out to have lived a much different life. He is the archetypal introvert poetic (romantic?) incel. Let others like him not make the same mistakes he did. We need to be open and communicate with one another in our movement and be willing to self reflect and overcome our personal flaws. In another life Lovecraft could have had a loving family and contributed even more to European civilization. I‘m sure he‘s looking down from the abyss right now smiling at us for what we‘re fight for.

Indeed, a cautionary tale to be sure.

Might look at various media productions which appear to have been inspired by H. P. Lovecraft…

The Outer Limits episode “Cry of Silence” (1964). Eddy Albert and his TV wife drive into a valley where they come under siege from mobile rocks, animated tumbleweeds and manic frogs. They encounter a farmer who has been possessed by an alien intelligence with strong implications of the Color Out of Space and The Whisperer in the Darkness.

Star Trek: The Next Generation episode 128 “Realm of Fear.” An Enterprise crewman encounters eel-like malevolent creatures in the transporter stream. The episode appears to draw inspiration from the Lovecraft short story “From Beyond” which was also made into a 1986 movie.

1998’s The Truman Show. This is stretching it a bit, but here Jim Carrey is trapped in an Innsmouth situation set in a seaside town which holds a sinister sorta secret. The big scene towards the end where he is being chased down by the townspeople-surrogates is similar to the climax of “Shadow Over Innsmouth.” Perhaps Truman’s escape is to just another television show?

Thanks for these suggestions. I’m familiar with Truman but the others are new to me. I can’t believe there’s an Outer Limits episode I don’t recall seeing, but perhaps it was so horrific I repressed all memory of it.

For more media of madness, one might peruse Von Junzt’s Undeplorable Multikulten, at least one annotated copy of which is rumored to exist in the library at Arkham Asylum.

Comments are closed.

If you have a Subscriber access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.