The Evolution of the Anti-War Film, Part Two: The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Travis LeBlancThe Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse is in the public domain. You can watch it here.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse is best remembered today for being the film that launched the career of Rudolf Valentino. It was an enormous success and the largest grossing film of 1921 beating out even the latest release by Charlie Chaplin who in 1921, was basically God. John Wayne said that The Four Horsemen was his favorite movie as a kid and he watched it twice a day for a week when the film passed through his hometown.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was based on a novel of the same name by Spanish socialist and naturalist writer Vincent Blasco Ibanez, which was itself the biggest-selling novel of 1919. I’ll admit that I’ve never read any of Ibanez’s books, but I’ve seen a few movie adaptations. His stories usually include a lot of sex and scandal in exotic locales: libertine Latin lovers, unfaithful spouses, and other trashy fun. In 1922, Valentino would have another hit with another Ibanez adaptation, Blood and Sand, where he plays a Spanish matador who embarks in an adulterous affair with a wealthy widow (watch it here). His two other most famous adaptations are The Torrent and The Temptress which are remembered for being Greta Garbo’s first two Hollywood films.

The Four Horsemen was released March 6, 1921, only two years and four months after the end of the Great War. It has been called a pioneering anti-war film. Maybe that was the intention of the people who made it. Maybe that is how the people who saw it at the time interpreted it. But watching it today, I can’t help but notice just how much wartime propaganda is still in it. There are even some themes that could be interpreted as pro-war.

For one, its portrayal of Germans is straight out of wartime propaganda. It still portrays the Germans as arrogant cultural chauvinists and barbaric warriors. It shows the Germans committing war crimes, executing civilians, and assaulting the maidenly virtue of French women. How much of that is based in reality is not the point. If your goal is to make an anti-war movie, that’s not how you do it. All Quiet on the Western Front portrayed the Germans as being no different from the kinds of regular Americans that you know in your daily life. That is how you make an anti-war film. I’m just speaking as a propagandist here. It undermines the anti-war message to portray one side as obviously more evil than the other. The film tries to balance this with some criticisms of French society as if to say “The French aren’t perfect either. They have their problems too!” But those criticism are much more subtle and understated than the criticisms of the Germans. I’ll explain that later.

But the flaws of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are part of what makes it interesting, at least from an academic perspective. It is a strange hybrid of well-intentioned pacificism mixed with still-unquestioned war propaganda.

The film begins in Argentina. We are introduced to the Madariaga, an ethnic Spaniard and a wealthy landowner. By the time he dies 20 minutes into the movie, he is the wealthiest man in Argentina. But Madariaga is not some effete upper-class twit. He is a rough and rugged cowboy. He spends his days riding throughout his lands on horseback and making sure all his workers are earning their wages. As a boss, he is strict but fair. As such, he is both respected and feared.

Madariaga has two daughters. The elder daughter marries a Frenchman named Marcello Desnoyers. The younger daughter marries a German named Karl von Hartrott. The intertitles tell us that Madariaga has a strong preference for the French family and doesn’t much care for the German family, which is never explained. Perhaps as a Spaniard, Madariaga prefers the French as fellow Latins. We are told that Papa Desnoyers is successful at business, which implies that Papa von Hartrott is not. Maybe that’s the reason.

As the film progresses, it becomes clear that the Desnoyers family and the von Hartrott family are metaphors for France and Germany respectively. This is one of the things that I found charming about this movie. It endorses a sort of folk race realism. Even though both the Desnoyers and the von Hartrott kids are raised in Argentina, they both come to display the stereotypical personality quirks of their respective Old World bloodlines. The Desnoyers act stereotypically French and the von Hartrotts act stereotypically German.

When the film begins, we are told that the von Hartrotts have three sons while the Desnoyers are still waiting on their first child. The von Hartrotts are pleased about this, because one day Madariaga will die, and having three sons will give them an advantage in getting Madariaga’s substantial inheritance. But much to the von Hartrott’s chagrin, Madame Desnoyers has a son. They name the son Julio and he grows up to be Rudolph Valentino. The Desnoyers later have a daughter named Chichi. So now that both the Desnoyers and the von Hartrotts have sons, who will acquire Madariaga’s inheritance is in doubt.

Before I go on, I need to say more about the von Hartraotts. Despite living in Argentina, Papa von Hartrott raises his sons to be hardcore German nationalists. When we first see the von Hartrotts, the children are shown playing soldier and marching in lockstep with each other. One of the kids walks up to his father and says “Down with Napoleon!” You see, they are not just playing soldier. They are specifically playing German soldier.

There’s another scene early on when it shows the von Hartrott family in their home. The intertitle states “Von Hartrott had reared his sons to respect the teaching of his Fatherland.” It then shows one of the von Hartrott sons reading a passage from a German book that reads “Man shall be trained for war, and women for the recreation of the warrior: all else is folly.” In the same scene, you also see that they have a picture of the goddamn Kaiser over their fireplace. This is just straight wartime propaganda: Germans are raised to crave war above all else and they are misogynist to boot.

Fast forward 20-ish years, and Julio Desnoyers has grown up to be a total stud. He spends his time cruising the bars of Buenos Aires drinking and chasing women. Despite the fact that Julio does not have a job or any ambition to do anything useful or productive, Maradiaga thinks he hangs the moon nonetheless. By now, Madariaga is an old man and takes pleasure in living vicariously through his impossibly handsome and charming grandson.

This brings us to the most famous scene in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Julio and Madariaga go to a bar together. Julio sees a woman he likes dancing with another guy. He walks up to the couple, pushes the guy away, and steals his woman like a pimp. They then do a tango dance together. Apparently, this scene was shoehorned in just to highlight Valentino’s dancing ability. I can believe it. It has little to do with the rest of the narrative. This scene ended up inspiring a tango fad in the US.

Julio invites the lady to come sit with him and Madariaga. At one point, Madariaga becomes so drunk that he falls off his chair. The lady makes some insulting remark about it. Julio pushes her away in disgust, lifts up his grandfather, and carries him back home. This scene tells us that Madariaga is close to death. He is old and can not hold his liquor like he used to.

Madariaga finally dies, and the Desnoyers and von Hartrotts show up for the reading of the will. By this point, the von Hartrotts are worried that Madariaga will leave his entire fortune to Julio, who was clearly his favorite. But when the will is read, both families are shocked to find that it calls for Madariaga’s fortune to be split 50-50 between his two daughters, giving the Desnoyers and von Hartrotts an equal share. The von Hartrott family is happy, because they were afraid they would get nothing. Julio is crushed. He was hoping to get Madariaga’s fortune so he could continue being an idle degenerate. Instead, he remains beholden to his parents.

Immediately after the reading of the will, Papa von Hartrott announces that his family will be returning to Germany forthwith. “I shall dispose of my share and return to my own country to resume my rightful position so that my sons may have the advantage of education and culture.”

Papa Desnoyers responds “But you can not do that, Karl. Madariaga always preached that where a man makes his fortune and raises his family — there is his true country!”

Papa von Hartrott is having none of it. “One owes his first duty to his Fatherland. That his children may grow up in allegiance with the advantages of super-culture.” Karl von Hartrott then leaves and his three sons follow him marching in lockstep with each other as if to emphasize the militaristic nature of their German essence.

This scene is an example of what I was talking about when I said this movie has some wartime propaganda vibes. Karl von Hartrott makes you want to not like Germans. So he loves his homeland of Germany and German culture. Fair enough. But he’s really condescending in the way he expresses it. He has no respect for anything that isn’t German. Argentina may have a culture but Germany has “super-culture.” He has no love for the country he’s lived in for the last few decades and only stayed there to bide his time until Madariaga croaked. Once he got his money, he had no intention of staying there a minute longer than necessary. He has no moral qualms about going against the wishes of the man who just made him fabulously wealthy. This is how you would want to portray Germans in a wartime propaganda movie, not an anti-war film.

After the Von Hartrotts leave, Mama Desnoyers says to Marcello, “Karl is right. We owe something to our children. Chichi could make a more suitable marriage in Paris and Julio study art. Why should you not return to your country?”

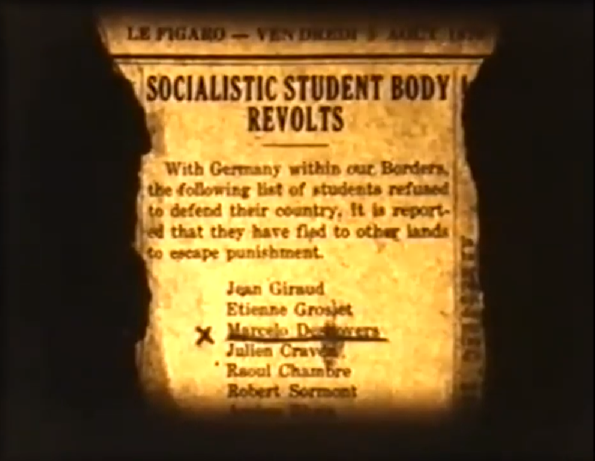

Why indeed? Here we learn that Papa Desnoyers has a skeleton in his closet. The intertitle tells us “Marcello Desnoyers has guarded the secret of his flight to the New World with fear and humiliation.” We then see Papa Desnoyers go to a dresser drawer and pull out a newspaper clipping whose headline reads “Socialistic Student Body Revolts.”

It turns out that Papa Desnoyers was a commie in his youth and dodged the draft in the Franco-Prussian War. Papa Desnoyers fled to Argentina rather than do his patriotic duty for his country in its time of need and he has been riddled with guilt ever since. Still, he allows his family to talk him into returning to France and the rest of the movie takes place in the Old World.

The Desnoyers have moved back to France and Marcello uses his share of Madariaga’s fortune to purchase a castle on the Marne river (what could possibly go wrong?). He also gets into the habit of going to auctions and splurging on jewelry for his wife and expensive trinkets to decorate the castle with. As a later intertitle puts it, “The castle on the Marne had become a colossal treasure palace — an altar to Desnoyers’ miserly bargain worship.”

“We will be bankrupt if he persists in this crazy bargain-hunting,” frets his wife. However, the Desnoyers daughter Chichi complains that while Marcello is fond of splurging, he is reluctant to give money to herself or Julio.

As for the Desnoyers daughter Chichi, Marcello has found her a husband with the son of a French senator named Lacour. When we first see the senator, Marcello is giving him a tour of the castle and showing off all his expensive possessions. “Now, Senator, you have seen my treasures destined for the castle, but this is my pride — a golden bath that once belonged to an emperor!” The senator’s son is a perfect gentleman, albeit something of a dullard. He and Chichi seem to hit it off well nonetheless.

Julio is now studying art in Paris, but for him, his artistic pursuits are just an excuse to hang out with pretty women. We see Julio in his art studio with three half-naked models. Julio is also frequenting tea dances where his tango-dancing skills make him a local sensation. He also starts an affair with Marguerite Laurier, the young wife of Etienne Laurier, a friend of Julio’s father.

The picture becomes clearer now. After raking the Germans over the coals via the von Hartrott family, we see that the Desnoyers are themselves avatars for French society. Whereas the German vice was arrogance, the French vice is decadence. Julio is a hedonist who has abandoned all traditional morality in pursuit of pleasures of the flesh. Papa Marcello Desnoyers has become obsessed with materialism as he squanders Madariaga’s life savings on useless things. He is also a draft-dodger who put his own personal comfort and safety ahead of loyalty to his people. Where the von Hartrott family displayed over-the-top collectivism, the Desnoyers are hyper-individualists.

Julio and Marguerite start going to tea dances together, but Marguerite, being married and well-known around town, starts getting uncomfortable being seen in public with Julio so frequently. People are starting to gossip about them so they instead start meeting up at Julio’s studio and their relationship deepens. Marguerite confesses to Julio that her marriage to Etienne was an arranged marriage and that she never truly loved him. Etienne eventually catches wind of his wife’s affair. He and Marcello go Julio’s studio to confront the two and they are caught red-handed. Etienne agrees to a divorce in order to avoid a scandal.

By this point in the movie, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand has been assassinated and they are in the middle of the July Crisis. France is soon at war. As a wave of patriotism sweeps France, Julio suddenly finds himself out of place in French society. Where he was once the center of attention, he for once finds himself a spectator. His pretty face and sensuous dancing are nothing compared to the monumentality of the events that are unfolding. As the intertitle puts it, “While the spirit of France responded to the call, the tango idol is forgotten.”

Here you start to see the beginning of a change in Julio. The people of France are responding as one to a higher calling greater than any of their individual selves. The streets of Paris are filled with poilus tearfully kissing their loved ones goodbye before fearlessly marching off on a holy mission to defend their homeland. Julio, a simple hedonist who never gave any thought to anything but his own amusement, starts to feel as shallow as he actually is. He may think of himself as a passionate lover, but that passion is nothing compared to the passionate spirit of honor and duty he is witnessing from the average poilu. Julio has been living a dishonorable life dedicated to avoiding real duty and for the first time in his life, starts to feel shame about it.

Like his son Julio, Papa Marcello Desnoyers is similarly overcome with guilt for being a draft-dodger 44 years earlier. The intertitle says “While all France answered the call to arms, Desnoyers was haunted by the unpaid debt to his country.” As Marcello watches the columns of poilus marching to the front, a man his age shows him a medal and says “I served in eighteen-seventy!” It’s an emotional punch in the gut for Marcello, and he hangs his head in shame.

Julio tries to carry on his affair with Marguerite — they even plan to marry as soon as she is free. And yet, he suddenly finds it’s not the same anymore. There is a scene where they are together in Julio’s studio. Marguerite is trying on her nurse’s uniform before she heads off to do her duty. She moves to kiss Julio but he hesitates. The sight of her nurse hat unsettles him. It symbolizes honor and duty and reminds him of his own inadequacy. She has to take off the hat before he can feel comfortable kissing her.

Marguerite then shows Julio a letter from her brother who is fighting in the same regiment as her husband. Part of it reads “You would not recognize Laurier. He is a great hero, no deed of bravery too daring, no risk too great.” Julio’s face sinks. While he may be younger, better-looking, and more charming than Marguerite’s husband — and he even stole his girl — Julio still understands on a gut level that her husband is a better man than him. Marguerite tries to make him feel better by saying “It is fortunate you are a foreigner and do not have to go. How horrible it would be to know you were in danger.”

Meanwhile, Chichi Desnoyers gets into a fight with her now-husband, the senator’s son. He has been drafted into the army, but his father has hooked him up with a cushy position away from the front in Paris. Chichi is very pleased by this. “How nice that it has been arranged for you to remain at home!” she says “I shall call you my little sugar soldier!” But the senator’s son is not happy about this. He wants to go to the front and fight like a real man, but his father will not let him and this causes some tension.

At this point, I have to say that this is some really weird messaging for a movie that aspires to be anti-war. Already we are hit with the message that people who fight in war are better than people who do not. All Quiet on the Western Front really tried to argue against this sentiment. Marcello feels like garbage for dodging the draft in 1890, Julio has an inferiority complex to the soldiers, and the senator’s son feels it’s dishonorable not to be at the front. Now, there may be some truth in that message. Serving in the military can be a character-building experience and coming face to face with death might give one some perspective on things. But why on Earth would include that message in an anti-war movie? That is something you would put in wartime propaganda.

I digress. Back to the narrative.

By now, the Germans are in France and the Great Retreat is underway. Refugees and retreating allies are streaming past the village outside the Desnoyers castle on the Marne. Shortly after that, the Germans arrive. French snipers shoot some Germans and so the Germans start shelling the entire village. By the time the Germans enter the village, all the buildings look like Swiss cheese. Some children are seen crying and trying to wake their dead mother. From here, the movie goes into full wartime propaganda mode.

The village is destroyed, but Desnoyers’ castle is still intact. The sneering arrogant Germans commandeer the castle and turn it into a headquarters. Marcello watches as some French civilians, mostly old men, are rounded up and executed for resisting in his front yard. Desnoyers goes upstairs and finds a German officer bathing in his prized golden bathtub. Desnoyers is heartbroken that his home and all his precious belongings are now being defiled by a hive of villainous Germans. He is being treated like a barely-tolerated annoyance in his own house.

But as luck would have it, one of the German officers turns out to be Otto, one of the von Hartott sons! Marcello pleads with Otto von Hartrott to use his influence to make the Germans leave his house, but von Hartrott, cold and unmoved, tells Marcello “What else can you expect? This is war!”

Then Marcello sees the Germans carrying out his prized golden bathtub. Marcello goes into a rage and tries to stop them, but Otto holds Marcello down while the Germans continue with their looting. Otto then says to Marcello, “It is well you are speaking Spanish. If you persist with such denunciations, a bullet will be the answer!” The villainous German threatens to kill his own uncle!

A few days later, it is Marcello’s nephew Otto who bluntly tells him that he will be executed for insulting a German officer (played by future Academy Award-winning actor Wallace Beery) who was about to rape his housekeeper’s daughter. Fortunately for Marcello, this does not happen, because an allied counter-offensive forces the Germans to withdraw from the castle in the morning. While Desnoyers’ castle manages to survive the Germans, it is ultimately destroyed by the Allies as they push the Germans back.

Meanwhile, Marguerite has left Paris without a word. Julio tracks her down in Lourdes where she is working as an army nurse. Her husband Etienne was blinded in battle and she has gone there to take care of him. Because Etienne is now blind, he is unaware that it is his own wife who is taking care of him. Julio is shocked, as they were planning to be married, but Marguerite tells him “Life is not what we thought. Had it not been for the war, we might have realized our dream. But now my destiny beside him is marked out forever.”

Julio now has an epiphany as he tells Marguerite: “How could I dare hope for your love. I have been a coward. But I will be one no longer! This country is yours! My father’s! I will fight for it!”

Julio returns to Paris to visit his father Marcello. Marcello is heartbroken that his castle has been destroyed and all his trinkets have been looted. He has refused to speak to Julio since discovering his affair with Marguerite, his friend’s wife. But when Marcello sees Julio in his French military uniform, he is moved. “My son, soldier, defending my country when it is not even yours!”

There is a special significance to this. Marcello ran from his obligation to fight for France in the Franco-Prussian War, and that has weighed on him his entire life. But now Julio is going to fight for France when he is under no obligation to do so. Metaphorically, Julio is repaying his father’s debt. While Marcello has lost all his worldly possessions, his son has given him the gift of a clear conscience, which is more valuable.

But before he heads off to war, Marcello gives his son a word of advice. “Family ties are not formed to our liking. Men of your own blood are fighting on the other side! But they are your enemies! If you meet them, do not spare them! Shoot! Kill!” He is of course referring to the von Hartrott sons, one of which treated Marcello as if he were their enemy.

The movie then fast forwards four years to 1918. The Americans have now arrived in France, and doughboys are shown dancing, joking around, and cooking doughnuts, a distinctly American cuisine. Julio runs into his father and the senator’s son on the street and they hug. Marcello gives Julio a box of treats from his mother and Julio immediately gives it to his fellow soldiers to enjoy. The senator’s son remarks “He is a different Julio! One hears everywhere of his unselfishness and his bravery.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UbvRXYTsRHk

Later we see Julio in the trenches. He has been assigned a dangerous mission to go out into no man’s land. However, over in the German trenches, one of the von Hartrott sons has also been ordered to go out on a similar mission into no man’s land. The two climb out of their trenches and stealthily crawl forward. At last, Julio and the von Hartrott son meet in the center of no man’s land. They each pull out a handgun but recognizing each other as their cousin, they both hesitate. Before either one can shoot the other, an artillery shell comes down out of nowhere, killing them both.

It then cuts to Marguerite and Etienne, who is still blind. Marguerite has been taking care of Etienne all these years, but her heart still belongs to Julio and this causes her much anguish. But at last, she has decided to leave Etienne and go back to Julio. She has written him a farewell letter, has her bags packed, and is ready to go. But just as she reaches for the door, the ghost of Julio appears before her. The ghost of Julio shakes his head at her and points to Etienne to let her know that where she belongs is by his side.

We then see Mr. and Mrs. von Hartrott at their home. They receive a letter in the mail informing them that their third and final son has died in action. Mrs. von Hartrott says to her husband “You are to blame! If we had followed my father’s teachings, we would not have left the Argentine and our sons would have been alive today!” So it turns out that the German know-it-all isn’t so smart after all. The old Spaniard Marariaga knew what he was talking about all along. Now, they are now childless.

The final scene takes place in a mass graveyard with row upon row of wooden crosses. Mr. and Mrs. Desnoyers and Chichi and her husband have come to Julio’s grave. The senator’s son finally got his wish to go to the front, and it appears that he got both of his arms blown off as a result. They are joined by Tchernoff, an eccentric and enigmatic Russian who lived in Julio’s building and was friends with Julio’s secretary. Tchernoff is a Rasputin-type: a stereotypical “mad Russian” and a mystic. The title of the movie The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse comes from a speech he gave earlier in the movie.

Marcello asks Tchernoff if he knew his son. Tchernoff extends his arms out, Christ-like, and says “I knew them all.” He continues: “Peace has come but the Four Horsemen will still ravage humanity, stirring unrest in the world until all hatred is dead and only love reigns in the hearts of mankind.”

The End.

So that’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. I liked this movie. I enjoyed it very much. I would describe it as “a good movie.” But it is a terrible anti-war movie. I’m not sure it ever would have dawned on me that it was supposed to be an anti-war movie were it not for the fact that every article about it says it is one. But analyzing it as propaganda, I kept saying to myself “What were they thinking?”

The problem that sticks out the most to me is the message that one can find redemption in war. Before the war, Julio was a hedonist and a coward who thought only of himself. But after joining the war, he becomes kind, unselfish, and brave. Marguerite was an adulteress, but then war comes and she feels compelled to become a faithful wife. That is a very romantic way of looking at war.

Whether there is any truth in that is not the point. It is the opposite of an anti-war message. If you were a parent with a good-for-nothing kid and watch this movie, then war starts sounding like a good idea. Send the rascal off to the front. Maybe he will learn to be a decent human being like Julio did.

And this theme undermines what anti-war message is in the movie. Julio dies in the war and that is sad. But he died an honorable man. Without war, he would have lived, sure, but he would have lived on as a sinner. If you were a Christian, as most people watching this movie in 1921 were, which would you prefer: that Julio die young and go to heaven or live to old age and go to Hell? Naturally, you’d probably prefer he go to heaven. In that case, you’d be thinking “Well, it’s a good thing for Julio that war broke out.”

There’s also the virulent anti-Germanism of the movie. I felt bad for Julio dying and I felt bad for seeing the senator’s son with his arms amputated, but I felt nothing for the von Hartrotts. If I felt anything, it was Schadenfreude when they got their comeuppance. If I were to be generous, I would say this movie sends mixed signals about war. “War is bad and causes a lot of suffering, but man, those Germans are some real assholes, aren’t they?”

A pure anti-war movie that aspires to portray war as something truly tragic should have no good guys or bad guys. This movie clearly does. Part of this might be due to the movie having been made so soon after the war that there was still some lingering afterglow of wartime hysteria.

Another problem is that if you are going to make an anti-war movie about the Great War, France is probably the worst country to set it in. Of all the great powers in WWI, France was the only country to enter the war involuntarily. Austria mobilized against Serbia; Germany, Russia, and Britain entered the war in defense of allies; and Italy, being full of Italians, took a bribe. But France was invaded and they had no way of preventing it. What was the alternative to war for the French? Just let their country be invaded? There have been anti-war WWI movies from the French perspective. Paths of Glory and the 1936 movie The Road to Glory were from the French perspective. But I see those more as criticism of the French high command than of the war, because again, what else were the French supposed to do?

Again, despite its shortcomings as propaganda, I really like this film. It is wonderfully shot, includes some strong performances, and the sets are really nice.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

The%20Evolution%20of%20the%20Anti-War%20Film%2C%20Part%20Two%3A%20The%20Four%20Horsemen%20of%20the%20Apocalypse

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Will There Be an Optics War II?

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

Der Krieger und der Stadtstaat

-

Civil War

-

The Holocaust Card Can No Longer Be Played

-

Problém pozérů aneb nešíří se snad myšlenky pravicového disentu až příliš rychle?

2 comments

reading a passage from a German book that reads “Man shall be trained for war, and women for the recreation of the warrior: all else is folly.”

The quote is from Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra.

The film you like was remade by Vincente Minnelli as The 4 Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962), with the setting changed to World War II. (SPOILER: the Nazis are the baddies.) Even the presence of Yvette Mimieux (Weena in The Time Machine!) and Carl Boehm (Peeping Tom!) couldn’t save it from the critics’ wrath.

The “anti-war” message of WWI propaganda was that everybody wants to live in peace except for those nasty heel-clicking Krauts who read Nietzsche all the time and are the sole reason for this war. French propaganda claimed that it was all about “humanity”, the “human race” or the “civilised world” fighting against the Huns. This was repeated in WWII, and today still many people believe it only got started because of senseless German/Nazi maliciousness.

Guy Maddin parodied the WWI anti-“Hun” propaganda in his (wonderful) neo-silent-talkie-hybrid “Archangel” (1991):

https://youtu.be/LFcYQgkhxMc?t=130

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.