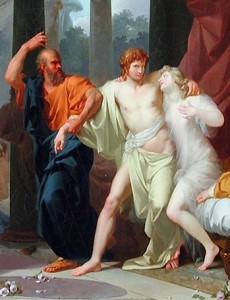

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I, Part 1

The Greatest Pick-Up Line of All Time

Greg Johnson

2,700 words

Part 1 of 5 (Part 2 here)

Author’s Note: I am typing up and editing my lecture notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I and Gorgias to incorporate them into a new book tentatively entitled Tyranny and Wisdom: An Introduction to Platonic Philosophy. The Phoenician neoplatonist philosopher Iamblichus (c. 245–c. 325) placed the Alcibiades I first and the Gorgias second in his curriculum of Plato’s dialogues, and with good reason, for together they constitute an excellent introduction to Socratic moral and political philosophy.

To read this, get behind our Paywall

Notes%20on%20Platoand%238217%3Bs%20Alcibiades%20I%2C%20Part%201%0AThe%20Greatest%20Pick-Up%20Line%20of%20All%20Time%0Aandnbsp%3B%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Related

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 583: Judd Blevins on His Recall and Pro-White Politics

-

What Went Wrong with the United States? Part 1

-

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

-

Remembering Sam Francis (April 29, 1947–February 15, 2005)

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy Rozdział 2: Hegemonia

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 1: Nowa Prawica przeciw Starej Prawicy

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

2 comments

I would love to see your upcoming book on Platonic thought. Your writings on Aristotelian philosophy are among my favorite articles of yours on Counter-Currents.

Thanks. Take a look at The Trial of Socrates. I am very proud of that book.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.