Svengali & the Transformation of an Anti-Semitic Hit

Travis LeBlancGeorge du Maurier’s gothic horror novel Trilby is all but forgotten today, and to the extent that it is remembered, it is for introducing the term “svengali” into the popular lexicon. “Svengali” has been used as a term for the power behind the throne of an entertainer. He is more than just a business manager who negotiates contracts, although he may do that as well. A svengali is a puppeteer for whom the performer is his own creative outlet. He cultivates the performer’s image and makes artistic decisions for them. Infamous svengalis include Malcolm McClaren of the Sex Pistols and Bow Wow Wow, and 1990s boy band svengali Lou Pearlman of the Backstreet Boys and N’Sync. Billie Eilish’s brother is her own svengali.

Svengali was originally the name of the villain in Trilby, a Jewish music instructor who takes an unrefined working-class girl and turns her into a famous opera singer. As Svengali says in the novel, “I cannot sing myself, I cannot play the violin, but I can teach.”

Forgotten though it may be nowadays, to merely call it “popular” when Trilby was first published in 1894 would be a gross understatement. It was a full-blown pop culture phenomenon on both sides of the Atlantic and widely hailed by both critics and commonfolk alike to be one of the greatest novels ever written. It inspired songs, parodies, and rip-offs. It was also adapted as a play and then performed by several companies that toured the country simultaneously to satisfy the demand. Even then, theaters frequently sold out and had to turn people away.

Merchandise of every conceivable type was produced and a fashion craze emerged, all inspired by Trilby’s enchanting title character, Trilby O’Ferrall, a free-spirited, half-Irish bohemian girl living in 1850s Paris. There were Trilby-themed sausages, soap, cosmetics, board games, and dolls, as well as a conspicuous increase in the number of baby girls named Trilby. There was also a surge of public interest in, as well as women wanting to become art models (Trilby O’Ferrall’s profession in the story) as a direct result of the novel. Trilby was in fact so popular that there is a town in Florida named after it.

There was also the “Trilby hat,” similar to a fedora but with a shorter brim. One of them was originally worn in a London stage production of the story, and the name “Trilby hat” stuck. Frank Sinatra wore trilby hats and they’ve recently become trendy among women, with Britney Spears being a fan.

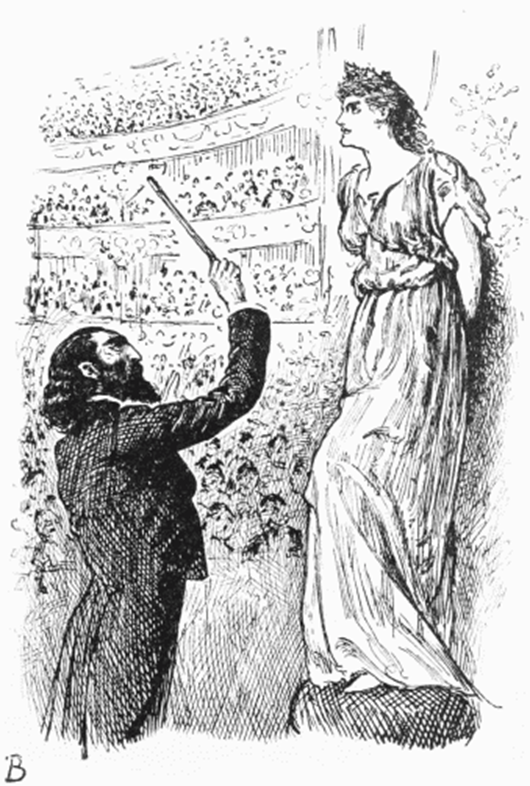

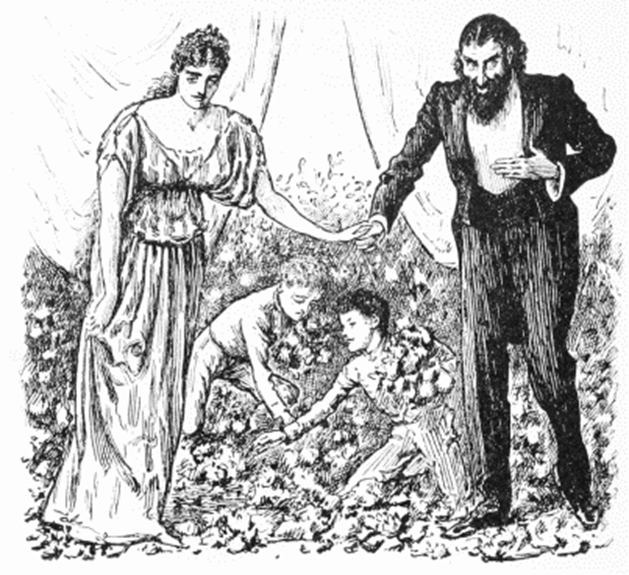

George du Maurier was a cartoonist for Punch before he started writing novels, and much of Trilby’s popularity was due to the 120 illustrations he included in the original novel. We know this because when Trilby was first released in Britain, it did not have the illustrations and sold sluggishly. The second printing, which included the illustrations, became a sensation there as it had in America. The most iconic image of the novel appears when Trilby is first introduced, when she is wearing a man’s military jacket over her dress. It became a fashion trend among American women.

Trilby O’Ferrall was a sort of proto-flapper. As a product of the Paris counterculture, she was a non-conformist and did not adhere to traditional gender expectations. She was sexually liberated, had affairs, and posed naked for rooms full of young, male art students. She wore men’s clothes and did things that were usually reserved only for men. Trilby is also credited with making it fashionable for women to smoke, something that the title character frequently engages in.

Despite all her degeneracy, Trilby O’Ferrall is still intrinsically good-natured and undeniably likable, and all the other characters in the book naturally fall in love with her. The paradox of her moral ambiguity was much of her appeal. Trilby is a kinda-sorta “hooker with a heart of gold.” She’s “immoral,” but not necessarily a bad person. She’s an orphan, after all, and doesn’t really know any better.

How did Trilby go from zeitgeist to obscurity? Part of the explanation might be its author, George du Maurier. He didn’t start writing until late in life and died two years after Trilby’s publication, before he could establish a solid literary legacy. Part of it could also be changing tastes and sensibilities. Some of Trilby is certainly outdated. Much of the plot revolves around hypnosis, which in 1894 was new and mysterious. But there is a an even likelier reason for Trilby’s memory-holing.

In 1946, a half-century after Trilby was first published, George Orwell reread the classic. He described the book as a

justly popular novel, one of the finest specimens of that ‘good bad’ literature which the English-speaking peoples seem to have lost the secret of producing. . . . to me the most interesting thing about it is the different impressions one derives from reading it first before and then after the career of Hitler. The thing that now hits one in the eye in reading Trilby is its antisemitism.

Trilby is about middle-class British art students. Talbot “Taffy” Wynne, William “Little Billee” Bagot, and Sandy McAlister arrive in Paris in the 1850s and meet the impossibly charming laundress and art model Trilby O’Ferrall, falling in love with her. But there is also an evil Jewish musician and voice instructor named Svengali who like Trilby, although she finds him repulsive. Svengali has the Jewish black magic of hypnosis, however, and he persuades Trilby to agree to hypnosis in order to cure her chronic headaches — but once under hypnosis, Svengali brainwashes her into becoming his slave.

You can buy Jef Costello’s The Importance of James Bond here

Trilby gets engaged to Little Billee, but the marriage is broken up by his family, who doesn’t want him marrying a woman of which there are hundreds of amateur paintings of her naked circulating around France. Trilby runs away and Little Billee goes back to England depressed, yet a famous and successful artist nonetheless. Years later, the old gang get back together and goes to the opera to hear this new singer, Madame Svengali, who has been amazing audiences all over Europe. When they go, they find that the singer is none other than their old pal Trilby O’Ferrall, and that she is now the wife of the dirty Jew Svengali!

See, earlier in the story it is a plot point that while Trilby has an angelic speaking voice, she is tone deaf and can’t carry a tune to save her life. But when she is under Svengali’s hypnotic power, she is able to sing in perfect pitch. Although since she is only able to sing when she is in a trance, she has no memory of having a singing career the rest of the time. Thus, when Svengali dies at the end, Trilby is suddenly unable to sing on key and is laughed off the stage. Trilby dies of grief for Svengali shortly after his death, and then Little Billee dies of grief for Trilby shortly after her death.

Speaking of the novel’s villain, Orwell writes:

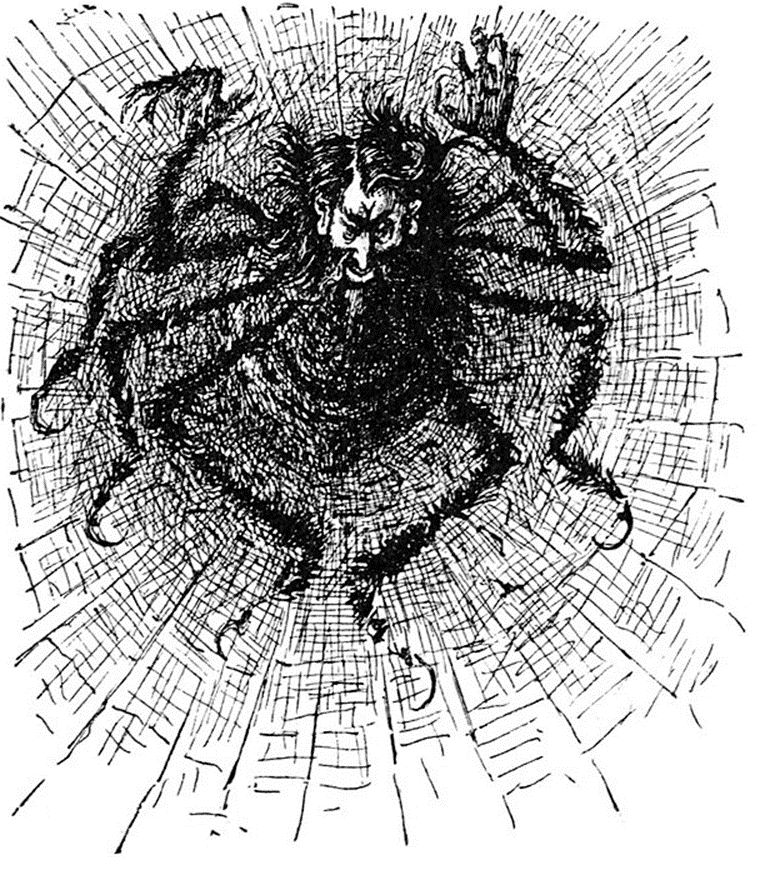

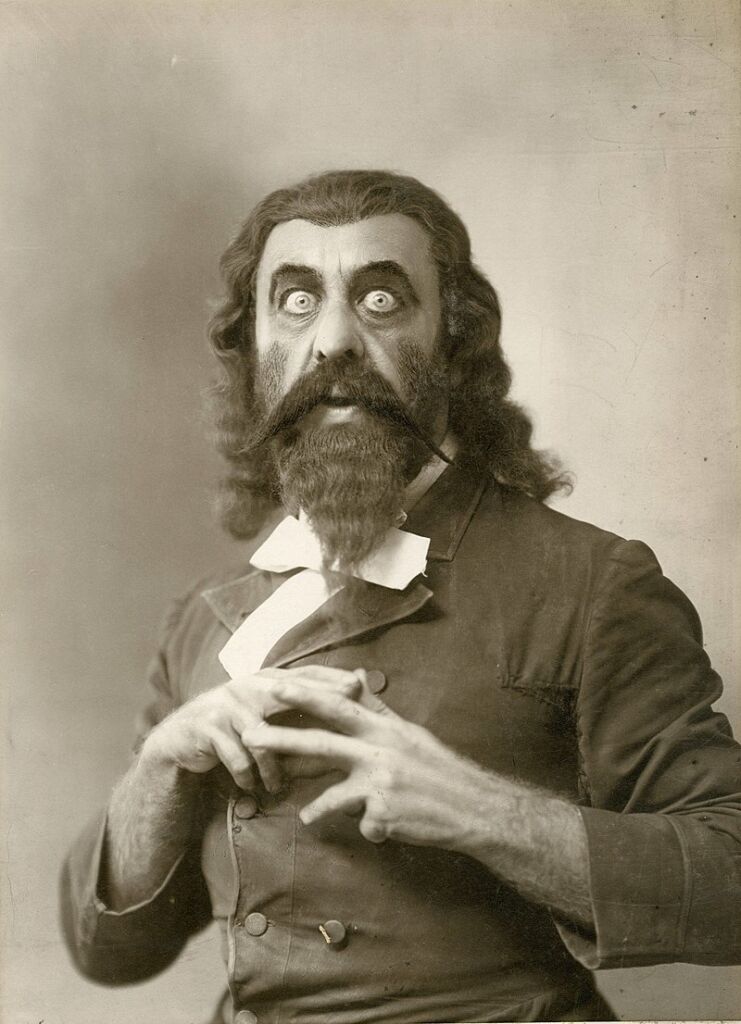

Apart from the fact that Svengali’s vanity, treacherousness, selfishness, personal uncleanliness and so forth are constantly connected with the fact that he is a Jew, there are the illustrations. Du Maurier, better known for his drawings in Punch than for his writings, illustrated his own book, and he made Svengali into a sinister caricature of the traditional type. . . . The fact that du Maurier chose a Jew to play such a part is significant. Svengali, who cannot sing himself and has to sing, as it were, through Trilby’s lungs, represents that well-known type, the clever underling who acts as the brains of some more impressive person.

Although Orwell also notes that there the late nineteenth-century, Dreyfus Affair-era anti-Semitism of Trilby differs from modern and more ideological forms of it:

To begin with, du Maurier evidently holds that there are two kinds of Jew, good ones and bad ones, and that there is a racial difference between them. There enters briefly into the story another Jew, Glorioli, who possesses all the virtues and qualities that Svengali lacks. Glorioli is ‘one of the Sephardim’ — of Spanish extraction, that is — whereas Svengali, who comes from German Poland, is ‘an oriental Israelite Hebrew Jew’. Secondly du Maurier considers that to have a dash of Jewish blood is an advantage.

Indeed, du Maurier describes Little Billee in a passage from Trilby thusly:

. . . in his winning and handsome face there was just a faint suggestion of some possible very remote Jewish ancestor — just a tinge of that strong, sturdy, irrepressible, indomitable, indelible blood which is of such priceless value in diluted homœopathic doses, like the dry white Spanish wine called montijo, which is not meant to be taken pure; but without a judicious admixture of which no sherry can go round the world and keep its flavor intact; or like the famous bull-dog strain, which is not beautiful in itself; and yet just for lacking a little of the same no greyhound can ever hope to be a champion. So, at least, I have been told by wine-merchants and dog-fanciers — the most veracious persons that can be. Fortunately for the world, and especially for ourselves, most of us have in our veins at least a minim of that precious fluid, whether we know it or show it or not. Tant pis pour les autres!

Of this Orwell writes:

Clearly, this is not the Nazi form of antisemitism. Svengali has ‘genius’, but the others have ‘character’, and ‘character’ is what matters. It is the attitude of the rugger-playing prefect towards the spectacled ‘swot’, and it was probably the normal attitude towards Jews at that time. They were natural inferiors, but of course they were cleverer, more sensitive and more artistic than ourselves, because such qualities are of secondary importance. Nowadays the English are less sure of themselves, less confident that stupidity always wins in the end, and the prevailing form of antisemitism has changed, not altogether for the better.

It was not unusual in the late nineteenth century to see explicitly Jewish villains in popular novels. One of the most famous examples is Fagin, the Jewish ringleader of the child pickpockets in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. But Dickens is too big to cancel, and Trilby lays it on pretty thick at times with references to “filthy black Hebrew sweep” and “bold, black, beady Jew eyes.” One of du Maurier’s illustrations of Svengali portray him as a spider, echoing later anti-Semitic propaganda portraying world Jewry as an octopus with tentacles sprawled all over the globe.

Trilby was adapted to film many times during the first half of the twentieth century. What’s interesting to note is that the earlier adaptations were all called Trilby, while all the later ones were called Svengali. While the original Trilby craze was fueled by fascination with the character of Trilby, as the decades went by attention shifted to the villain Svengali, until he eventually became the title star.

The best-remembered adaptation of Trilby is the 1931 Warner Brothers film starring a then-unknown 17-year-old Marian Marsh as Trilby along with acting legend John Barrymore as the villainous Svengali. This was in fact the sixth film adaptation of Trilby. Trilby O’Ferrall would have been a highly coveted role at the time, as women did not get many opportunities to play “edgy” roles. The fact that Marian Marsh landed it as a newcomer was an extraordinarily lucky break. The lore is that Barrymore personally selected Marsh due to her resemblance to his wife, Dolores Costello, and that due to her inexperience, Barrymore coached her on her acting. In other words, in an episode of life imitating art, Barrymore was Marsh’s literal Svengali during the making of the movie.

Marian Marsh is radiant in her role, while John Barrymore plays Svengali as a low-down son-of-a-bitch. In the opening scene, one of his talentless bimbo music students announces that she has left her husband, just as Svengali had suggested (under his hypnotic influence, as we learn later). Alas, the woman tells Svengali that she refused to accept a settlement from her husband out of principle and threw the money back in his face when he tried. Crestfallen, Svengali dumps the woman, and she commits suicide the next day. This establishes immediately that Svengali is psychopathic. Further, the film goes to great lengths to stress the fact that Svengali does not bathe. He is a truly loathsome figure.

The stage and film adaptations of Trilby have tried to downplay Svengali’s Jewishness. In the 1931 film adaptation it is not mentioned at all apart from a passing reference to Svengali being from Poland. Barrymore strikes me as trying to play Svengali as a sort of Rasputin type — a mad Eastern European. The infamous Russian mystic Rasputin rose to prominence only a few years after Trilby’s publication, and his strange relationship with the Russian royal family drew comparisons to Svengali during his lifetime. The makeup artist gave him a very large and suspicious-looking nose, however.

There is some debate as to whether Svengali qualifies as a horror movie, and there are a few reasons why one would think that. It came out during horror-movie boom of 1931, which also saw the release of the classic Universal horror pictures Dracula and Frankenstein. Also, John Barrymore’s eyes change color and start glowing when is performing hypnosis, suggesting that his mind-control abilities are similar to, say, Dracula’s hypnotic powers. (He also speaks with an over-the-top Eastern European accent, just like Dracula). One of Svengali’s catchphrases in the film is, “There are more things in Heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy” suggesting that his abilities are supernatural.

There are many things in Svengali that can only be explained by the supernatural. Besides hypnosis, Svengali also has the power of telepathy. When he dies, his hypnotic slave Trilby dies as well for no apparent reason. Thus a case could be made for categorizing it along with Dracula and the rest, although Barrymore hams it up in such a campy way that it really cannot be taken seriously as a horror movie.

The film’s director, Archie Mayo, is underrated. Unless you are a nerd for pre-code Hollywood, you’ve probably never heard of him. He was a B-team director for Warner Brothers and never had a classic hit, but he made a lot of good lesser-known movies featuring some big stars, including my all-time favorite, The Petrified Forest. He had a great sense of mood which serves him well here.

That Barrymore and Marsh give such solid performances make everyone else pale by comparison. Bramwell Fletcher was cast as Little Billee, Svengali’s doomed romantic rival, and he is easily blown off the stage. I had never heard of Bramwell before, and he doesn’t seem to have gone on to do anything noteworthy. Much of the original story was cut from the film, including Trilby’s tone deafness and the three British art students — each of whom have very distinct personalities in the novel, but get so little screen time that you never really get to know any of them.

Svengali ended up losing quite a bit of money, making back only half of its half-million-dollar budget — a tidy sum for the time. It may be that even by 1931, Trilby was starting to seem old-fashioned. The Jewish scoundrel archetype that Svengali represented was out of date. The Jews had Westernized considerably by then, shaving their beards, wearing Western clothes, and even taking baths. In any event, Jewish control of Hollywood guaranteed that a faithful adaptation of Trilby was never going to happen.

While doing research I discovered that there is a Canadian radio drama adaptation of Trilby from 1983 called La Svengali. What’s interesting about it is that it tries flip the story on its head, portraying Svengali as the good guy. The English artists are casually anti-Semitic about Svengali behind his back in it, and you are made to feel sorry for him because of that. Rather than hypnotizing Trilby into becoming an opera star as part of his quest for money and power, he is merely an artist using Trilby to get the music in his soul out into the world.

There was also a made-for-TV adaptation of Trilby made in 1983 that starred Jodie Foster and Peter O’Toole in which Foster is the singer in a bar band who gets taken under the wing of a vocal coach on her way to stardom. But the less is said about this adaptation, the better.

Svengali%20andamp%3B%20the%20Transformation%20of%20an%20Anti-Semitic%20Hit%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Related

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

Five Years’ Hard Labour? The British General Election

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Birch Watchers

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

-

The Worst Week Yet: April 28-May 4, 2024

1 comment

Very good, Trav. This is one of those things I long had in my trunk as possible fodder for Counter-Currents entertainment. Many years ago I bought an entire set of DuMaurier novels from G. Heywood Hill in Curzon Street in London. But I found Trilby (that’s the novel) pretty much impenetrable. Who would even care about these people?

I recall that Svengali himself was seldom referred to as a Jew, but rather as a “Pole.” Perhaps this was a common euphemism in the London of its day, much as “American” would be a few decades later.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.