The Evolution of the Anti-War Film, Part One: The Players

Travis LeBlancTucker Carlson recently ruffled some feathers for calling WWI “the Iraq War of its day.” I’m not sure what these people were offended by. I think there are just people who get outraged by the things Tucker Carlson says first before coming up with a reason why, and they just never got around to the second part this time.

It’s an entirely appropriate analogy. Like the Iraq War, WWI was extraordinarily popular with the American people at the time, but buyer’s remorse set in very quickly.

As longtime Trav readers know, I enjoy trying to understand history by looking at what movies were popular at different times. WWI is a particularly interesting subject to do this with. The United States entered the Great War in 1917 and it ended in 1918. During those years, the Great War enjoyed enthusiastic public support across all segments of American society — so much so that there was extensive violence against ethnic Germans in US cities.

However, 1930 saw the release of All Quiet on the Western Front, a brutal, remorseless, full-throated, and unapologetic denunciation of the Great War. In my opinion, All Quiet on the Western Front is the ultimate anti-war movie. Paths of Glory can go to Hell. All Quiet on the Western Front is the alpha and the omega of anti-war films. It strips war of all its romanticism and portrays it as pointless suffering devoid of glory or heroism. It presents the Great War as the godforsaken abomination that it was.

All Quiet on the Western Front would go on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture (or Outstanding Production as it was called at the time) and would be the third highest-grossing movie of 1930. The top-grossing movie of that year was Whoopee!, a film starring Jewish comedian Eddie Cantor, which is now considered wildly racist and includes a scene of Cantor performing in blackface. The second highest-grossing movie of 1930 was Check and Double Check, an Amos ‘n’ Andy film starring two white guys in blackface. It would appear that the only thing more popular than hating war in 1930 was racism. Ah, those were the days. . .

So it only took 12 years, from 1918 to 1930, for America to go from total war hysteria and bloodlust to being stridently antiwar and isolationist. I’m not going to delve too deeply into all the reasons for how that came to be. That is an entirely different conversation.

Instead, I will look at two landmark films about the Great War that came out between 1918 and 1930. The first is 1921’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and the other The Big Parade from 1925. Looking at both these movies, you can see how the attitudes towards the Great War gradually changed during those 12 years. Both films were the largest grossing movies of the years in which they were released, so we can safely assume that they reasonably reflected (or at least were not antithetical to) the attitudes of the American moviegoing public at the time.

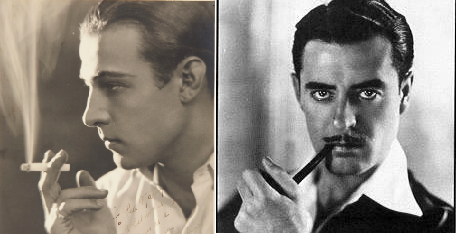

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and The Big Parade are highly similar. They are both stories about the idle sons of wealthy men who feel compelled to go off and fight the Hun after the outbreak of the Great War. Two of the most popular onscreen lovers of the silent era star in them: Rudolph Valentino and John Gilbert. I’ll say a bit more about them later.

Before we get into it, I’ll give some background on WWI and film.

The Great War was the first major war after the invention of the motion picture. Well, that’s not entirely true. There is some film footage from the Second Boer War. You can see some here and here. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the Great War was the first war after the emergence of the modern film industry. It was the first time when you had movies being made about the war while the war was still going on.

However, the anti-war film is actually older than the Great War. The first-ever anti-war movie was a Belgian film called Maudite soit la guerre (Damn the War). You can watch it here. It was filmed in 1913 and released in May 1914, three months before the outbreak of the Great War. Maudite soit la guerre was ahead of its time in two ways, first for pioneering the anti-war genre, but also for anticipating aerial combat. When the Great War broke out, airplanes were initially only used for reconnaissance, but in Maudite soit la guerre, planes are shown doing strategic bombing and air-to-air combat.

One of the things I have always found striking is the vast difference in how WWI is portrayed in movies versus how WWII is portrayed. With rare exceptions, WWI movies are almost always anti-war, and WWII movies are almost always pro-war. There are some notable exceptions.

The biggest exception is movies about the air war in WWI (Wings, Hell’s Angels, The Blue Max). These are generally given the glamor treatment (“knights of the air”), and there are a few reasons why. For one, it’s said that the air war was the only part of WWI where individualism still mattered. Surviving the trenches often came down to blind luck. You could be the biggest badass in the world, but if you were standing at the wrong place when an artillery shell came down, all your training, skill, and morale would count for nothing, which seems incredibly unjust. However, in the air, you won a dogfight by being a better pilot than the other guy. There were all sorts of death and pointless violence in the air war, but at least there was some degree of meritocracy. Plus, there’s the fact that being a fighter pilot looks like it would be kind of fun. It probably wasn’t, but it looks fun watching it on the screen. I consider movies about the air war a separate animal from the classic WWI movie.

The second exception would be that there were some WWI movies released in WWII for propaganda purposes. The most famous pro-war WWI movie is probably the 1941 Gary Cooper movie Sergeant York, a true story about the wartime service of Alvin York, a hardcore Christian who overcame his moral qualms about taking human life to become the Rambo of the Great War. With America creeping towards another European war, it was necessary to try to rehabilitate the last one. Sergeant York was a major success. You can watch it here.

Aside from those two exceptions, WWI movies lean pretty heavily anti-war. Perhaps only movies about Vietnam are more consistently anti-war. But this was not always the case. During the three years between the outbreak of war in 1914 and the United States’ entrance in 1917, both pro and anti-war movies were made.

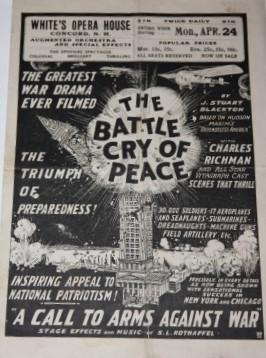

On the pro-war side, the most notorious of these was The Battle Cry of Peace in 1915. In it, American peaceniks are used as unwitting pawns by a foreign dictator to keep America weak. America is then invaded by foreigners and the White House is burned down. Teddy Roosevelt, America’s foremost war advocate, was a big fan. It was the second most controversial film of the era after Birth of a Nation. Alas, it is now a lost film.

Speaking of Birth of a Nation, that movie was based on a book called The Clansman by one Thomas Dixon. Dixon attempted to capitalize on the success of Birth of a Nation by making a sequel, The Fall of a Nation, about America being invaded by a German-led confederation of European nations. A pro-war congressman and a suffragette join forces to raise an army to expel the foreign hordes. This movie is also lost, but you can read the book.

On the anti-war side, the most significant movie was 1916’s Civilization. It’s a very silly movie and its plot is too convoluted to describe in one paragraph. If you are interested, you can watch it here. I’ll just say that it ends with Jesus Christ giving the warmongering king of a fictional European nation a tour of the Great War battlefields until the king calls his soldiers back home. As silly as it is, Civilization was an enormous success on release, and Woodrow Wilson, who ran on an anti-war platform, credited the film with helping him win reelection.

After the controversy around Birth of a Nation, director D. W. Griffith spent the rest of his life trying to make up for it. He would later make Broken Blossoms about a sympathetic Chinaman who befriends a white girl with a cruel and abusive father, and one of his last films was a biopic about Abe Lincoln. His immediate follow-up to Birth of a Nation was Intolerance. Intolerance is probably best remembered today for its absolutely stunning set design of ancient Babylon. But at the time, Intolerance was intended as an anti-war film. The film ends with a chorus of angels appearing over the Great War battlefields calling the people to peace. You can watch Intolerance here.

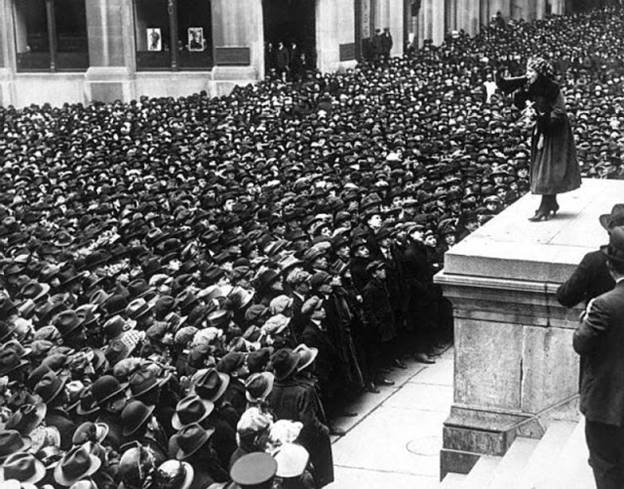

Intolerance proved just a modest success, because only a few months after its release, the United States entered the Great War. Americans were now bloodthirsty and were in no mood for any hippy crap about the virtues of peace. Hollywood went into full war propaganda mode and released a wave of anti-German war films, many of which had wonderful titles like The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin, To Hell with the Kaiser!, The Claws of the Hun, The Prussian Cur, and The Hun Within. All of the major Hollywood stars were recruited by the United States government to go on speaking tours to sell war bonds.

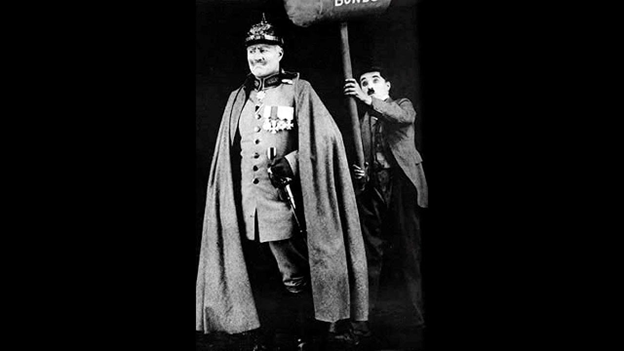

Charlie Chaplin made two war propaganda movies, The Bond and Shoulder Arms, which you can watch here and here. Mary Pickford, the most popular actress in the world, was an enthusiastic supporter of the war and made several propaganda films for both the United States and her native Canada. Her 1917 film The Little American (watch it here) was considered so anti-German that it was banned in Chicago for fear that it would start a riot. Her studio Artcraft (which later become Paramount) had to sue the city in order to get it shown there.

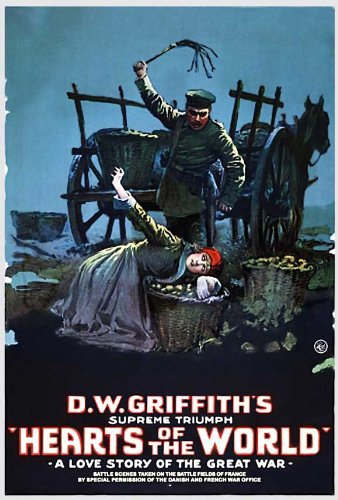

D. W. Griffith, who two years before had made a film denouncing the war, was recruited by the British government to make a propaganda film promoting it. The result would be 1918’s Hearts of the World, about a French village that becomes occupied by the Germans. You can watch it here.

When the Great War ended in November 1918, the American public lost interest in war movies as their attention became fixed on other more immediate social issues, like prohibition and the women’s suffrage movement.

The next major Hollywood films about the Great War would be The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in 1921 and The Big Parade in 1925. By then, attitudes about the war had begun to evolve. The post-war world wasn’t looking quite how people expected it to, and the sight of amputees walking around had become common. This would naturally cause some people to start questioning what the hell the war was fought for.

But before we dive into comparing those films, we shall take a brief look at the stars, Rudolph Valentino and John Gilbert, as they were both major cultural icons of the 1920s and comparing them is an interesting exercise in itself.

Going just by their onscreen personas, Rudolph Valentino and John Gilbert present a sort of yin and yang. Valentino was the smoldering oversexed Latin while Gilbert represented dignified WASP chivalry. They were the perfect avatars for the two perennial female fantasies: the rakish bad boy and the knight in shining armor.

And yet biographically, the two had a lot in common with each other. Aside from being preposterously handsome, they both came from humble origins. They both had minimal stage experience before getting into movies. After entering movies, they both started at the very bottom playing extras and uncredited bit parts before working their way up to box office mega-stardom. They both became romantically involved with lesbians with disastrous results. And most importantly, they both died tragically young.

Rudolph Valentino was born with the comically long name Rodolfo Alfonso Raffaello Pierre Filiberto Guglielmi di Valentina d’Antonguella in 1895 in the Apulia region of Italy (that’s the heel of Italy’s boot) to an Italian father and a French mother. He immigrated to America in 1913 and spent his first years bumming around New York City doing odd jobs and supplementing his income as a dime-a-dance taxi dancer. It was a thing back then that you could club and hire a person to dance with you. Taxi dancing was considered a pretty shady profession, and was often used as a front for prostitutes to meet potential clients (for female dancers) or to find lonely rich married women seeking adventure (for male dancers).

For someone famous for being irresistible to women, Valentino’s love life was one catastrophe after another. While in New York, he took up with a very wealthy and very married Chilean heiress who ended up murdering her husband during a nasty custody battle. Valentino’s involvement in the highly publicized scandal rendered him unemployable in New York, so he headed out West to California.

Valentino was constantly dealing with rumors that he was gay, although no concrete evidence for this exists. I think a lot of speculation about this or that celebrity being secretly gay is wishful thinking on the part of jealous player-haters or from gays themselves. This is why you hear a lot more rumors about Tom Cruise and Cary Grant being secretly gay, but comparatively few about Dom DeLuise or Steve Buscemi.

But there are some autobiographical details about Valentino that give one pause. A person who loomed large over Valentino’s life was one Alla Nazimova. Nazimova (real name Marem-Ides Leventon) was a Russian-born Jew and a popular film actress in her own right, but more than that, behind the scenes, Nazimova was Queen Bee of Hollywood’s gay mafia (which was a thing even back then). Her parties were infamous for their debauchery and her appetite for women was voracious. She slept with scores of women, including famous novelists, actresses, poets, directors, and even Oscar Wilde’s niece. Alla Nazimova was also Nancy Reagan’s godmother, which, come to think of it, might explain a few things.

Nazimova played a key role in lobbying for Valentino while he was still a struggling unknown actor. Valentino’s first wife, Jean Acker, was a lesbian and Nazimova’s ex-lover. Why Acker married Valentino is anyone’s guess. She reportedly locked him out of her bedroom on their wedding night and the marriage was never consummated. That didn’t stop her from calling herself Mrs. Rudolph Valentino after he hit the big time. Acker spent their marriage living in a separate residence with her lesbian lover, actress Grace Darmond. I can only imagine how much lesbian street cred Darmond must have had being able to claim that she stole Rudolph Valentino’s woman. Anyway, the nature of this first marriage has caused some to suspect that it was a “lavender marriage.” Why else would a guy who could have any woman he wanted choose a lesbian to be his wife unless he was gay himself?

Valentino’s second wife was Winifred Shaughnessy, who was better known by her professional name Natacha Rambova. She was a costume designer and protégée of Alla Nazimova, which probably explains the exotic Russian-sounding pseudonym. Valentino attempted to marry Rambova before his marriage to Acker was finalized. Acker responded by pressing bigamy charges against him, which resulted in him being thrown in jail for a couple of weeks. Whether Rambova was a lesbian or not is disputed, but she was by all accounts an unpleasant person and would prove to be Valentino’s Yoko Ono. She alienated many of his friends and persuaded him into some of his worst business decisions and biggest commercial flops. Valentino was in the process of divorcing Rambova when he died suddenly in 1926 from a stomach condition that is now named after him. 100,000 people showed up to his funeral.

In his five years as an A-lister, Valentino was a national heartthrob playing various Latin lovers. His biggest hit was The Sheik, about a romance between a white woman and an Arab sheik. At the end of the movie, it is revealed that the sheik’s parents were actually English and Spanish and that the white woman is not a race-mixing whore after all.

John Gilbert is not as well-remembered as Rudolph Valentino. To the extent that he is remembered, it is for three things. First, he is remembered for starring in The Big Parade, and to a lesser extent, The Merry Window, one of the few commercial successes of eccentric genius Erich von Stroheim before he was blacklisted from directing. Second, he is remembered for the movies he did with Greta Garbo and for their subsequent romantic relationship. The third thing is that along with Norma Talmadge and Gloria Swanson, John Gilbert is one the go-to examples of someone who was a titan of the silent screen who failed to transition into talking pictures. To understand that third bit, you have to understand the second.

The legend is that when people heard John Gilbert’s voice for the first time, it was high and effeminate and nothing like what they expected the suave onscreen lover to sound like. This is largely an urban myth. Judging from the talking pictures he made, his voice was fine and reminiscent of William Powell, who was an A-list star in the 30s and 40s.

Swedish actress Greta Garbo made her Hollywood debut in 1926 and was an instant phenomenon. In her third film, Flesh and the Devil, she was paired with John Gilbert and their onscreen chemistry was electric.

In her early silents, Garbo was like a female Valentino. Whereas a Valentino movie might revolve around him seducing a married woman or innocent ingénue, in Garbo’s movies, she would be the unscrupulous married woman trying to seduce honorable men into an affair that would violate their code of ethics.

To understand Gilbert as an anti-Valentino, Flesh and the Devil is a great example. In it, Gilbert plays a German soldier who meets and falls in love with Garbo only to find out that she is married to some rich jerk. The jerk challenges him to a duel and Gilbert kills him. He then goes off to German colonial Africa to give things time to cool off, and spends the next few years dreaming of the day he can return and resume his romance with Garbo. When he at last returns, he finds that Garbo is now married to his best friend. A Valentino-type character would have no qualms about screwing his friend’s wife, but Gilbert is tortured between his feelings for Garbo and loyalty to his friend as Garbo continues to pursue him.

Shortly after Flesh and the Devil, Gilbert and Garbo became romantically involved and were the Brangelina of the late silent period. Unfortunately for Gilbert, Garbo was almost certainly lesbian or at very least a gay-leaning bisexual. Legend has it that back in Sweden, Garbo had a lesbian affair with a Jewish woman she met in acting school who broke her heart and she never got over it. Garbo carried a torch for the Jewess for the rest of her life and died alone.

Nevertheless, Gilbert and Garbo were engaged to be married. However, on their wedding day, Garbo failed to show up. As they were waiting for her, Jewish MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer made a crude comment about Garbo, which resulted in Gilbert punching Mayer to the ground. Mayer then set about trying to deliberately ruin Gilbert’s career. Mayer assigned him to movies with inexperienced directors and bad scripts, movies he knew would tank. The scheme worked and Gilbert’s career went into a steep decline, and he became severely alcoholic. He would marry and divorce two more times. He finally died in 1936 at age 38 due to health problems related to alcoholism.

At the time, he was dating Marlene Dietrich, another notorious Hollywood bisexual.

Some guys never learn.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

The%20Evolution%20of%20the%20Anti-War%20Film%2C%20Part%20One%3A%20The%20Players

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

The Fall of Minneapolis

-

Adolph Schalk’s The Germans, Part 1

-

The Search for the Holy Grail in Modern Germany: An Interview with Clarissa Schnabel

-

Travis LeBlanc Against Right-Wing Cancel Culture: A Rebuttal

-

Why Right-Wing Cancel Culture Is a Bad Idea

-

How the South Beat Reconstruction, Part 3

-

In the Beginning: Plato’s Timaeus

-

The Bikeriders

10 comments

One of the very greatest anti-war films is “Wooden Crosses” (“Les Croix de Bois”) (1932), directed by Raymond Bernard.

Both All Quiet on the Western Front and Intolerance are great, but now I’ll have to check out Whoopee!

I’ll recommend von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives. It’s not really an anti-war film but does show the aftermath of WW1 and the Russian Revolution.

Stroheim started his career playing cartoonish “evil huns” during WWI (and repeated this shtick again in WWII). He would also occasionally play sympathetic German officers, for example in Renoir’s “Great Illusion”. There is a curious early talkie, “The Lost Squadron”, where he plays a “Teutonic” tyrant film director, shooting a “Western Front” style war movie, parodying his own image (like Otto Preminger he was actually a Viennese Jew).

The changing Hollywood attitude towards Germans may be seen in “Flesh and the Devil” among others (like Murnau’s “Sunrise” based in a Hermann Sudermann novel), but also, more relevant to this very interesting article, in John Ford’s “Four Sons” (1928), an excellent, Murnau-influenced anti-war movie from a German p.o.v., similar to “Western Front” in many respects.

There were two stereotypes of German soldiers in Hollywood movies, sometimes juxtaposed: the negative “Prussian”, monocled, heel-clicking sadist (early Stroheim’s speciality, involving into the archetypical “Nazi” of WWII and beyond), and the positive stiff-but-gallant knightly warrior (the Red Baron/ Richthofen type), who sometimes realised he was fighting on the wrong side (like Anton Wohlbrück/Walbrook in “Life and Death of Colonel Blimp” or Reginald Gardner in “The Great Dictator”).

Stroheim’s character in The Lost Squadron was based on Howard Hughes and the movie was inspired by the making of Hell’s Angels. The movie was an adaptation of a book by a pilot named Dick Grace who walked out of the making of Hell’s Angels because Hughes wanted him to do an insanely dangerous stunt for $250. Hughes ended up getting someone else to do it for $1000. I think they made the character German to avoid a lawsuit.

Wiki has a “List of anti-war films”, but there is no corresponding list of pro-war films. No movie has the message that war is an intrinsic good, but rather that some things are important enough to fight for. (300 may be the only exception.)

But, as Uncle Freddy observed: “You say it is the good cause that hallows even war? I say unto you: it is the good war that hallows any cause.” And H.L. Mencken observed: “Every normal man must be tempted, at times, to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats.”

Maybe, I’ve spotted a gap in the market.

The Green Berets and Saving Private Ryan is the ones which pop into my head (where is the Unz Review’s Priss Factor when you need him?). Neither are particularly nice films I’d argue.

Of course, Wayne avoided being drafted in WW2 and Saving Private Ryan is about how you dehumanise German people for two hours. Vile film once it has been pointed out and one that can turn you off the concept of modern film making.

Also, I don’t think notorious Isolationist Mencken would have put his longing for pirate swashbuckling with warring sentiments.

The Green Berets ending.

KILLING PRIVATE KRAUT – Saving Private Ryan film analysis

Saving Private Ryan is about how you dehumanise German people . . . Vile film.

Completely agree. Similarly, The Dirty Dozen with Lee Marvin has a great opening, but a later scene in which Wehrmacht officers and their ladies are killed with grenades and petrol left a bad taste in my mouth. I’m supposed to approve?!

On Mencken’s pirate swashbuckling: as a war-comic reading lad, I saw German U-boat wolfpacks as modern buccaneers. Vicious little brat, wasn’t I?

Erich Von Stroheim: ‘The man you love to hate.’ It’s interesting he was cast as Rommel in Five Graves to Cairo. Also, in Sunset Boulevard, as Norma Desmond’s (Gloria Swanson) butler. Interesting because Stroheim directed Swanson in films during their heyday. When he drives Norma’s antique Isotta Fraschini limousine, it was a chore because he didn’t know how to drive. He was exhausted after each take, although the car was bring pulled by ropes.

Also, the kinky scene where he is shown hand washing Norma Desmond’s underwear was suggested by Stroheim.

As for WWI, a lot of people were burned out because as ‘the war to end all wars’ it seemed to end up as a power grab at Versailles, much like all that good Civil War rhetoric of Abe Lincoln saving the union and malice toward none ended in Reconstruction and a thoroughly corrupt America bossed around by monopolies.

For a long time, it was felt nothing was worth WWI. I noted at the centennial, naturally it was tarted up as a great noble cause for…yeah, baby…’freedom.’

Noted the number of talk show hosts and their followers who bleated ‘if America hadn’t intervened, we’d all be speaking German.’ Christ.

As for movies and the effect the war had on Hollywood, reading Gore Vidal’s novel Hollywood reflects this, as Caroline Sanford, his newspaper publishing heroine, goes to Hollywood and gets cast in war films taking on the Hun, and discovers what an effective power film has to penetrate people’s subconscious, which is part of Vidal’s theory that Hollywood then began its power to remake people’s desires and needs, and so control society. As she observed, ‘Reality could now be entirely invented and history revised. Suddenly, she knew what God must have felt when he gazed upon chaos, with nothing but himself upon his mind.’

A book about WWI I like is Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun, dealing with a horribly maimed soldier that is very anti-war, and has good writing on character scenes. It was published in 1939, immediately censored by the government, and pulled out of libraries, republished in the 1960’s.

Sergeant York: okay, but a bit hokey when York, wondering if he should be drafted or not, is on a mountaintop reading his Bible, and the wind suddenly flips the Bible to pages urging a righteous war, etc. Really getting us ready to sign up for war.

Great article, but my grandfather was a combat pilot in WWI. There was nothing romantic or heroic about it at all. They lost planes on every single sortie; sometimes none came back. He flew heavy bombers, which had virtually no defensive capabilities against the lighter, swifter dogfighters. If you were caught, it was death. Convinced he was doomed if he continued fly, he sought a transfer to a ground unit and got it. Ironically, he was shot through the chest by a German sniper and barely survived. Madness!

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment