Masterpieces of (Honorary) Aryan Literature 5

Yukio Mishima’s My Friend Hitler

Quintilian

Yukio Mishima

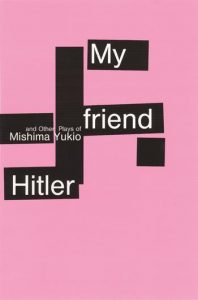

My Friend Hitler and Other Plays of Yukio Mishima

Translated by Hiroaki Sato

New York: Columbia University Press, 2002

Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) is best known as a novelist and Right-wing activist who famously and publicly committed ritual suicide in 1970 one day after he had finished his tetralogy The Sea of Fertility. He was, however, a very prolific playwright with more than sixty plays to his name, most of which were produced during his lifetime, often with Mishima performing one of the lead roles. My Friend Hitler was first produced in 1969, and in one production Mishima performed the role of Hitler.

The play is an attempt at an objective analysis of the thinking that went into the Roehm Purge of 1934, what is commonly known as the Night of the Long Knives. In this event, Hitler disposed of his good friend Ernst Roehm, the leader of the SA, who had been threatening to initiate a second “revolution” in which the SA would replace the German Army. In eliminating Roehm and vastly decreasing the size and influence of the SA, Hitler secured the loyalty of the leadership of the German Army and its acquiescence to Hitler’s assumption of the powers of the Reich presidency after Hindenburg died, thereby consolidating Hitler’s dictatorial authority.

The three-act play has just four characters: Hitler, then industrialist Gustav Krupp, Roehm, and Gregor Strasser, a former Nazi leading light who was a leader of the “socialist” wing of the NSDAP. It is June 1934 and Hitler is delivering a speech from the balcony of the Chancellery. As he is giving his speech, Krupp, Roehm, and Strasser sit in Hitler’s office, debating the next phase of the German “Revolution.” Hitler finishes his speech, and Roehm and Strasser make their cases respectively for “Right” and “Left” courses for the future of the Reich. Hitler asks Roehm and Strasser to meet with him the next day for breakfast, at which time Hitler will elaborate upon his plans for the future. Roehm and Strasser leave, and when Hitler remarks to Krupp that he has reached a moment of decision, Krupp responds, “You aren’t up to it, Adolf; you aren’t up to it yet . . .”

In Act II, Roehm appears at the Chancellery for breakfast. He and Hitler reminisce about their years of struggle to assume political power. Strasser never appears. When Roehm leaves, Krupp appears from behind a curtain where he has been eavesdropping at Hitler’s behest. As Roehm leaves the Chancellery, he is confronted by Strasser, who tells Roehm that they must put their differences aside in order to remove Hitler from office and continue the German “revolution.” If they don’t, Hitler will have both of them killed. Roehm scoffs at Strasser, rejects his offer, and proclaims his loyalty to “my friend Hitler.”

Act III begins after Roehm and Strasser have been assassinated and the events of the Night of the Long Knives have been set in motion. Hitler arrives back in Berlin and finds Krupp waiting for him at the Chancellery. Hitler relates to Krupp the events that have transpired, and the play ends with this dialogue:

Krupp: (He sits comfortably in a chair) I should say. We can now leave everything to you without any worry. Adolf, you did well. You cut down the left and, as you turned the sword back, cut down the right.

Hitler: (He walks to stage center) Yes, government must take the middle road.

The play is remarkable for its emphasizing the political thinking and rational weighing of choices that went into Hitler’s decision to purge Roehm and the SA and many other enemies rather than concentrating on the gory consequences of that decision. In so doing, Mishima makes Hitler’s use of trumped-up charges of treason against Roehm appear to be little different than George Bush’s false allegations of the presence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq as a reason to depose Saddam Hussein, rather than attacking the true perpetrators of 9/11. Whether it be Bush’s “compassionate conservatism” or Hitler’s “middle road,” Mishima reminds us that true nationalism and the interests of the Volk are always in danger of being subverted by the Krupps and the others among the globalist elites whose only allegiances are to their bottom lines.

Masterpieces%20of%20%28Honorary%29%20Aryan%20Literature%205%20Yukio%20Mishimaand%238217%3Bs%20My%20Friend%20Hitler

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Mechanisms of Information Distribution

-

Overturning Roe v. Wade

-

When The Temperate Is Decried as Extreme: A Review of When Harry Became Sally: Responding to the Transgender Moment

-

A Nice Place To Visit: Lovecraft As The Original Midnight Rambler, Part 4

-

Prepping for Kids

-

Pass It On: Vladimir Volkoff’s La Grenade

-

A Nice Place To Visit: Lovecraft As The Original Midnight Rambler, part 3

-

A Nice Place To Visit: Lovecraft as the Original Midnight Rambler-Part 2

5 comments

I read this in my sophomore year of college. …In the library, by myself. Strong words about destruction, sadism, and pure totalitarian spirit.

This book made more sense when I read “The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima” by Jerry Piven. I recommend that one as well.

The last sentence here is especially pertinent today.

Great article, thank you.

I’m having trouble understanding the last sentence, as I’m ignorant of this event and of who Roehm, Strasser, and Krupp were. Could someone please explain this to me?

Is it drawing a parallel between Hitler and Bush, and insinuating that both were not acting in the true interest of the people who they governed? Or were the ones Hitler disposed of threats to true nationalism?

Thanks

A brief explanation.

In 1934, members of the SS and others attacked and killed at least 84 Nazis to consolidate Hitler’s power over the party. This event is referred to as the Night of the Long Knives. Two victims of the purge were Gregor Strasser and Ernst Roehme.

Strasser and his brother Otto (who left Germany) represented an economically socialist wing of the Nazi party.

Roehme headed up the SA, which had originally been a type of street army used by the Nazis.

Gustav Krupp was a wealthy German industrialist.

Mishima’s play uses these three figures to represent (1) the left wing, or socialist faction within nationalism – Strasser; (2) nationalism’s right wing faction -Roehme; and (3) the power of capital and capitalism – Krupp.

I don’t think Mishima was reflecting on any US political figure specifically; it’s the author of this review, Quintilian, who introduces Bush and Hitler as examples of a point. If I’ve understood Quintilian’s point correctly, it is that genuine political nationalism, whether ‘left’ or ‘right’ oriented, is in danger of being subverted or diluted by capitalism. This is a point I think is relevant today, given the power of our corporate media and its tendency to ignore/defame genuine nationalists in favour of big-business sock puppets who clothe themselves in nationalist icons but deliver more of the same.

.

I was annoyed that this translation appeared, wanted to do my own.Mishima’s literature is great, and his suicide really was a turning point (although it has led to morons like Abe an Aso, am not sure that it had true value). I have fascist friends who do a song ‘No Mishima, no future.’ Maybe I will still translate it.

Mishima was a gay man. Many believe that the final act was a love suicide with Morita.

Read Confessions of a Mask, for the most obvious, but the same theme appears in many others.

This is not to criticize, I love his writing, just think that much writing on it, particularly by nationalists, is lacking balance.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.