Tag: nature

-

3,644 words

This is the second part of the notes for a lecture entitled “The Conquest of Nature: Ayn Rand,” from October 1999. This was the seventh lecture of an eight-lecture course called “The Pursuit of Happiness,” delivered to my adult education group, The Invisible College, in Atlanta.

Ayn Rand wasn’t always an advocate of laissez-faire capitalism. Indeed, the early Ayn Rand was a Nietzschean with an aristocratic disdain for commercial society. (more…)

-

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

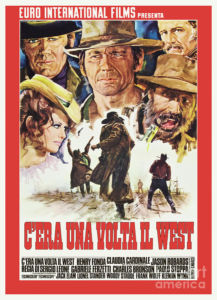

After the climactic gunfight between Frank and Harmonica, the latter and Cheyenne say goodbye to Jill. But just outside of the McBain property, Cheyenne falters. Harmonica stops and turns with concern. It turns out that Cheyenne was mortally wounded by Morton. Like Jesus, he has a bleeding wound in his side. This comes as some surprise. He must have been putting up a brave front with Jill. But the surprise comes off as a rather contrived plot twist; one of many. (more…)

-

Deep ecology represents a significant shift in the way humans understand and interact with the environment. This movement is rooted in the belief that our current models of human engagement with nature are unsustainable and destructive. Arne Naess, a Norwegian philosopher, first developed the concept of deep ecology in the 1970s, and it has since grown into a powerful environmental and philosophical movement that has inspired many to adopt a more holistic and sustainable approach to environmental issues. (more…)

-

You can buy the Imperium Press edition of Knut Hamsun’s novel Growth of the Soil here.

You can buy the Imperium Press edition of Knut Hamsun’s novel Growth of the Soil here.

2,229 words

If there is a novelist whose work needs a revival, it’s Norwegian author Knut Hamsun. And if there is any novel of his which deserves being revived, it’s Hamsun’s 1917 classic Growth of the Soil.

Since the Second World War, culture leaders in the West have deliberately neglected works of literature deemed politically inconvenient while promoting those that accord more or less with their globalist, Left-wing agenda. This is why stateless iconoclasts such as Franz Kafka are so celebrated these days while reactionary nationalists such as Hamsun are largely forgotten. (more…)

-

6,122 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

Rich Houck: There’s also other parts I find a small problem with. Ted Kaczynski seems to think that without these modern technologies, people cannot be controlled or subverted or treated poorly, but it seems to me that throughout history that’s not been the case. He talked about some of these movements. He mentioned Communism and Nazism in in the same line, as mass movements, but it seems to me that even if we can imagine a society where there’s no modern technology, you could still have a group of people come that is hostile to your interests for various reasons. (more…)

-

6,103 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here)

The following is an edited transcript of the conversation between Greg Johnson and Richard Houck on the subject of Ted Kaczynski’s manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future, that was broadcast on Counter-Currents Radio in April 2021. You can listen to the recording here.

Greg Johnson: I’m Greg Johnson. Welcome to Ted Talk. I am joined here today by Rich Houck, and we’re going to be talking about Ted Kaczynski’s Industrial Society and Its Future. Rich, welcome to the show. (more…)

-

I usually adhere to the Roman custom of only speaking well of the dead, but I will make an exception for Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGate and designer of the ill-fated Titan. As the Joker would say, “We live in a society.” OceanGate says a lot about that society, and I can’t help but see the funny side of the Titan’s catastrophic implosion. (more…)

-

6,312 words

Leo Strauss credited Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology as a critical resource for his project of overthrowing modern political thought and vindicating the ancients. This may come as some surprise to readers of Strauss, given the prominence of his critique of historicism, which applies to Husserl as well. But Strauss’s late essay, “Philosophy as Rigorous Science and Political Philosophy”[1] as well as posthumously published lectures and correspondence reveal significant debts to Husserl.

Husserl was not, moreover, a mere “negative influence” — i.e., someone whose ideas Strauss rejected. Husserl was a “positive influence,” meaning that Strauss accepted and incorporated some of his ideas. (more…)

-

6,912 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

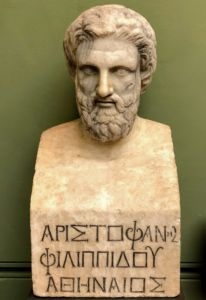

Strepsiades Flunks Out

It hasn’t gone well. First Socrates bursts out of the Thinkery swearing an oath: “By Respiration, by Chaos, by the Air.” The usual places of gods in his oath are occupied by three natural forces. Socrates then rants about a particularly bad student who is “rustic . . . resourceless . . . dull . . . and forgetful.” Then he calls this student to come out. And out comes Strepsiades.

Socrates then quizzes Strepsiades on what he has learned. (more…)

-

-

5,320 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

In the first part of this essay I introduced readers to Schelling, who is one of the first philosophers to react against what Heideggereans have called “the metaphysics of presence”: the hidden will in Western metaphysics that gives primacy to human subjectivity, adjusting our understanding of the Being of beings to the human desire that beings should be completely transparent to us, hiding nothing, and readily available for our manipulation. In response to this, Schelling argues that it is nature, not human subjectivity, that should be the starting point of philosophy. (more…)

-

4,839 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here)

1. Introduction: A Philosophical Rebel

This essay is a continuation of my series on “Heidegger’s History of Metaphysics.” With Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775-1854) we have reached a significant milestone, in a number of ways. Behind us, in our journey toward Gelassenheit, we have Plato, the philosophers of the Middle Ages, Descartes, Leibniz, Kant, and Fichte. Ahead of Schelling we have only two more philosophers to discuss, Hegel and Nietzsche, before we turn to cover in more detail Heidegger’s response to the metaphysical tradition and to modernity. (more…)