Archibald Roosevelt

A Brave Captain of the First World War

Part 1

Morris van de Camp

2,368 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here)

Archibald Bulloch Roosevelt was born in 1894 to Theodore and Edith (Carow) Roosevelt in Washington, DC while Theodore was serving as the United States Civil Service Commissioner. Archibald was named for an ancestor who had been a hero of the Revolutionary War, Archibald Bulloch of South Carolina.

Archibald Roosevelt is an important man to remember. He was a man of the Right, but he was not a populist, nor is there any hint that he was wise to the Jewish Question. He was however opposed to “civil rights” at a time when every fashionable person in America was in favor of the disastrous policy. The march of “civil rights” continues, for now, so Archibald didn’t stop it, but many of his anti-socialist ideas bore fruit. Indeed, Archibald’s metapolitical efforts helped to bring down the Soviet Union.

Archibald was the son of one of America’s great presidents, Theodore Roosevelt. He was the fifth of six children born to Theodore, and the fourth of five that his wife Edith delivered. All of Theodore’s children went on to great accomplishments; three died while serving overseas in the military. He mostly grew up amidst the splendor of Sagamore Hill, his parents’ sprawling estate on Long Island. His own son, Archibald Roosevelt, Jr., wrote:

Grandmother was an awesome chatelaine. She ruled the house and its unruly visitors in her soft and precise voice, an iron hand scarcely hidden in the velvet glove. Only when we were older did we realize she was small and frail. To us she seemed eight feet tall, and although she never raised that quiet voice, it could take on an icy tone that made even the largest and strongest tremble.[1]

He likewise said of his grandfather that Theodore’s “sprit permeated every corner of [Sagamore Hill], as well as the grounds outside.”

Archibald, Sr. thus had much to live up to. Not only was his namesake a war hero, but his father had been a famously successful military man a well. Theodore Roosevelt greatly improved the US Navy as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Following that success, Theodore Roosevelt joined the Army and successfully led the 1st US Volunteer Cavalry in Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

During the twentieth century many of the most effective actions favoring the interests of the white American Majority came from men who had been US Army captains during the First World War, and Archibald Roosevelt was one of that valiant number. Other such captains were:

- John Trevor (military intelligence): founded the Pioneer Fund, performed public service in various roles, and helped push through the 1924 immigration restrictions.

- John McCloy (field artillery): enacted the Japanese internments as Assistant Secretary of War and bravely defended the policy afterward.

- Albert Johnson (Chemical Corps): helped craft the 1924 Immigration Act as a Congressman from Washington.

- Ulysses S. Grant III (Engineer Corps): represented American Majority interests in many ways throughout his career.

- Merwin K. Hart (infantry): served in the John Birch Society and persuasively argued against the dead-end economic policies that were prevalent in the late 1940s.

- Bennett Champ Clark (infantry): allied with North Dakota’s isolationist senator Gerald P. Nye to keep American foreign policy free of foreign — especially Jewish — entanglements in far-off places.

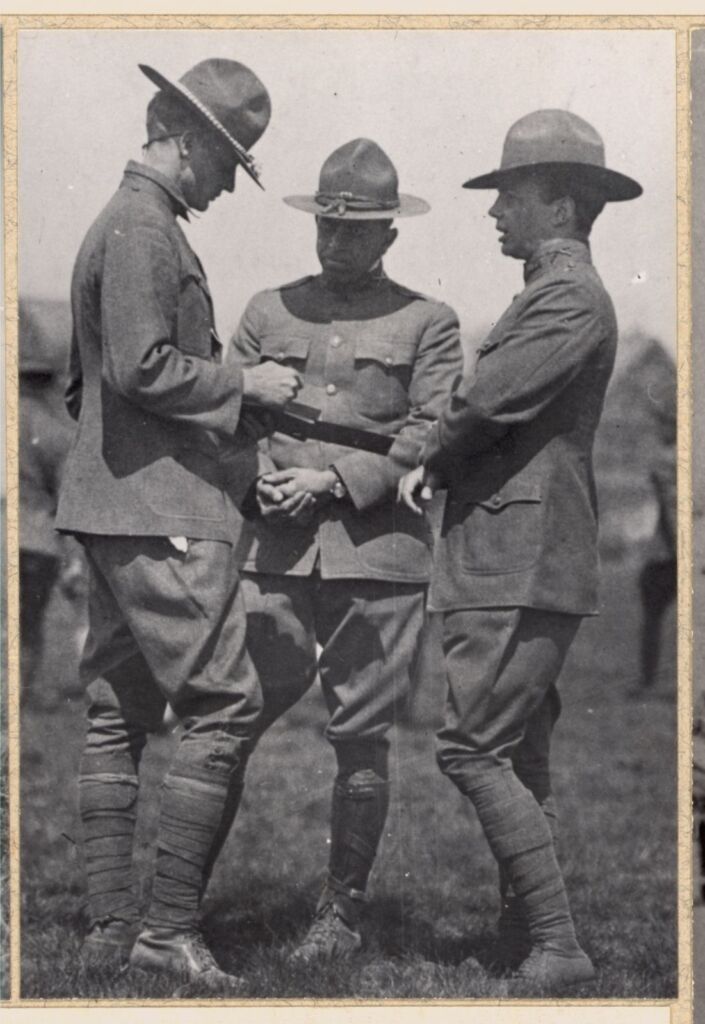

The First World War broke out in 1914, and America remained neutral, although some believed that it should be prepared for war. In 1916 Theodore Roosevelt’s former commanding officer, Leonard Wood, arranged for the setting up of a military leadership training camp in Plattsburg, New York. Young men, mostly from elite and wealthy WASP families, attended the camp; Archibald and his brothers were among those who signed up.

Archibald left the camp with a reserve officer’s commission as a Second Lieutenant. His older brother would receive a reserve commission as a Major. When war came just after Archibald graduated from Harvard in 1917, his father, Theodore Roosevelt, used his contacts in the War Department to send his sons to France along with the first American troops who were deployed. The First World War was indeed the last conflict in which nearly the whole of the American political elite encouraged their children to enlist and see action.[2]

Archibald and his brothers joined the Army. Quinten served in the Air Corps. Kermit joined, but then resigned to take a commission in the British Army, serving in the Middle East. Theodore and Archibald went to France with the first American soldiers to deploy. Archibald was assigned to the 16th US Infantry Regiment (First Infantry Division) as a First Lieutenant and was promoted to Captain shortly thereafter. Theodore joined the 26th US Infantry Regiment, which was part of the same division.

While in France, Archibald achieved success by going above and beyond what was expected. He worked to improve his troops’ rations by buying chickens from local farmers. He also donated books from his collection to the enlisted men in order to improve their knowledge and reduce boredom. He mostly focused on training. Archibald was later able to secure a transfer to his brother’s regiment. In March 1918, while in the trenches with the rest of the 26th US Infantry, he was struck by several shell fragments during an artillery bombardment. One of them broke his left arm and severed a nerve; another shattered his kneecap. His knee was so badly injured that at first it was feared that it would need to be amputated, but he eventually recovered. Archibald was awarded two silver citation stars and the Frech Croix de Guerre for his service.

After the war Archibald went into business, where he worked as an executive for the Sinclair Oil Company. But in 1921, he became embroiled in a scandal. The Secretary of the Interior, Albert Fall, leased oil reserves to private companies, one of which was Sinclair Oil, without holding any bidding. Fall received “loans” in exchange for these leases. The Democrats pounced on the scandal. Democrat Eleanor Roosevelt, who was Archibald Roosevelt’s first cousin, toured the United States in a car with a giant teapot affixed to its roof to keep the scandal in the public’s mind. Eleanor and Archibald’s relationship never recovered.

You can buy H. L. Mencken’s The Passing of a Profit and Other Forgotten Stories here.

Archibald ultimately resigned from Sinclair and testified in senatorial hearings on the matter. Albert Fall would go to prison for his misdeeds. Archibald hadn’t done anything illegal, so he went to work at Roosevelt & Sons, a Wall Street investment firm.

Then came the Second World War, and Theodore Roosevelt’s sons again did their duty. Kermit Roosevelt rejoined the British Army. Kermit was sent to North Africa in 1940, but began to drink heavily and was eventually discharged due to an enlarged liver and a case of malaria he’d contracted on an expedition in Brazil with his father. When Kermit returned to the United States, he continued to drink, so Archibald convinced the US Army’s Chief of Staff, George C. Marshall, to commission him in the US Army to keep him out of trouble. Kermit was sent to Alaska and served in an aircrew on bombing missions against the Japanese, who were holding some of the Aleutian Islands. Kermit’s best service in Alaska was forming a militia made up of Aleuts and Eskimos. Kermit was unable to defeat his demons, however, and died by suicide in 1943. His mother was told he died of a heart attack.

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.’s service during the war was legendary. He joined the First Infantry Division and served as its Assistant Division Commander. There he was involved in operations in North Africa and Sicily. Theodore and his commander, Terry de la Mesa Allen, were ultimately relieved by General George Patton due to professional differences between Allen and Patton. Theodore was transferred to the Fourth Infantry Division and went ashore with the first wave at Utah Beach on D-Day. His role was vital. The troops had landed in the wrong spot, so he issued adjusted orders to the follow-on units and sorting out traffic jams. He finally died in France on July 12, 1944 of a heart attack. He had had heart trouble and arthritis, but hid his ailments from the Army.

Archibald joined the US Army as well shortly after Pearl Harbor. He was 48 and initially deemed ineligible for service, but he wrote to the President Franklin D. Roosevelt to point out the political capital that he could win by having a cousin bearing the same name in uniform. The President gave him a commission as a Lieutenant Colonel and he was put in command of the third battalion of the 162nd US Infantry Regiment, which was part of the 41st Infantry Division. The division was made up of men from the western states: Washington, Idaho, Montana, and so on, although most of them were from Oregon. The division was sent to the Pacific, as American strategy in early 1942 was to prioritize operations in Europe while keeping Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii out of Japanese hands.

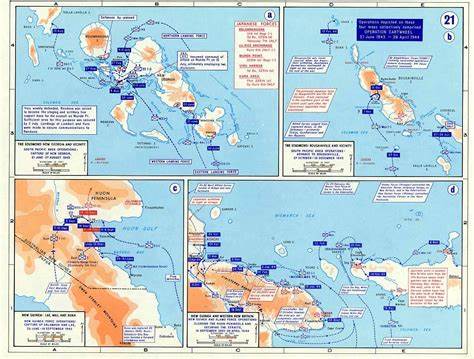

Australia in particular was under threat from Japan. The Japanese invaded the island of New Guinea in January 1942, which was then divided between the colonial Dutch East Indies and the Australian colonies of Papua and New Guinea. They established formidable bases there, the main one being at Rabaul.

The Australians responded to the threat by building the Brisbane Line, a series of defensive positions which ran west of Brisbane. Australia’s military leaders eventually realized that the Japanese would likely bypass the Brisbane Line and directly invade the populated southeast from the sea. Furthermore, Australia needed 25 divisions to successfully resist a Japanese attack, and many Australian military units had already been deployed to North Africa, Ceylon, and Burma and couldn’t be recalled. The Australians thus realized that the best way to deal with the problem was to invade the island of New Guinea and remove the Japanese before they could use the island as a staging base for a large invasion force.

The Brisbane Line was the Australian military’s plan to defend against a Japanese attack. They reasoned that the Japanese would invade from the north, but they later realized that the Japanese could easily bypass the Brisbane Line by sea and strike the capital, Melbourne, from the south. It turned out to be a moot point, however, once the Japanese threat was ended by retaking the Japanese positions in the islands north of Australia, especially New Guinea.

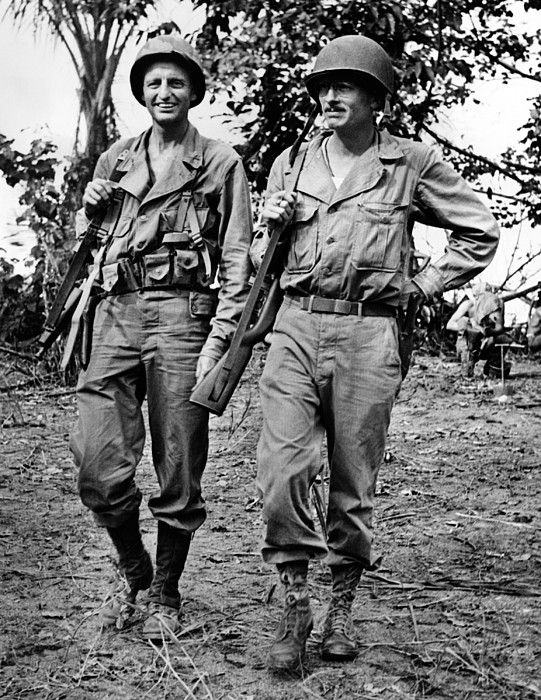

The 41st Infantry Division arrived in Queensland in July 1942, where it underwent training in jungle warfare and amphibious operations. The 162nd Infantry didn’t deploy to fight the Japanese until late June of the following year. The first part of the regiment to see action was the MacKechnie Force, which consisted of regimental headquarters, the first battalion, and supporting artillery, as well as Australian soldiers. They landed at Morobe, a town near Nassau Bay, to establish a base for a larger push on the Japanese positions at Salamaua. In late June, Archibald’s third battalion took over the defense of Morobe from the MacKechnie Force.

The 162nd Infantry’s actions in New Guinea were part of a much larger operation that overwhelmed the Japanese. By mid-September the Japanese had been completely expelled. Historian John Miller wrote:

The cost was not cheap. On 29 June [1943] there were 2,554 men in the 162nd Infantry. By 12 September battle casualties and disease had reduced the regiment to 1,763 men. One hundred and two had been killed, 447 wounded. The 162nd estimated it had killed 1,272 Japanese and reported the capture of 6 prisoners.[3]

One of the wounded men was Archibald Roosevelt, as he had once again been hit in the knee by a grenade fragment. He wouldn’t rejoin the 41st Infantry Division until 1944.

The New Guinea campaign was a masterstroke of offensive military operations which featured cooperation between the Allies’ respective armies and navies. The Australians and Americans successfully deceived the Japanese as to when and where their next moves would take place and attacked several places at once. Overall it went well; the Japanese were often attacked while they were sick and starving. But the New Guinea campaign was plagued with race problems.

One such problem occurred in the 92nd Infantry Division, a segregated sub-Saharan division. The 92nd’s performance had been uneven, and in Australia, things were worse. Ground troops from a sub-Saharan unit at an airfield staged a mutiny which had to be put down by Australian forces. Lyndon Baines Johnson, then a Congressman with a US Navy reserve commission, was sent to sort out the mess, and his report on it was kept classified for decades. Archibald Roosevelt would have been aware of the 92nd Division’s issues and may have caught wind of their mutiny. He was also aware of the racial problems that had existed during his father’s career. When the “civil rights” movement began in the late 1940s, Archibald became involved in a metapolitical effort to oppose it.

Notes

[1] Archie Roosevelt, Jr., For Lust of Knowing: Memoirs of an Intelligence Officer (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1988), p. 4.

[2] During the Second World War most elite families encouraged their sons to enlist, but not all. Those who were appointed to West Point were considered shirkers, since frontline commissions were available and West Point cadets weren’t expected to deploy. This situation is the first inkling of the American Majority’s dispossession, as well as that of a loss of civic virtue on the part of the old-stock American elite. By the time of the Korean War, the situation was the same as today. The late Pat Robertson, a Christian-Zionist televangelist, served in the US Marine Corps during that conflict but later embellished his service record. Robertson was the son of a US Senator and was therefore transferred out of combat duties. During the Vietnam War, most of the political elite avoided service completely. No Vietnam veteran has won the presidency, and only one Vice President, Al Gore, has served in a combat zone. George W. Bush’s daughters didn’t serve in Iraq or Afghanistan, and Crooked H never saw a war she didn’t want other people’s children to fight.

[3] John Miller, Jr., The War in the Pacific, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1959), pp. 202-203.

Archibald%20Roosevelt%0AA%20Brave%20Captain%20of%20the%20First%20World%20War%0APart%201%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Related

-

True Christian Nationalism

-

Notes on Plato’s Gorgias, Part 13

-

Adolph Schalk’s The Germans, Part 2

-

Adolph Schalk’s The Germans, Part 1

-

Virginia Is Where America was Born

-

Nowa Prawica przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 15: Ten dawny liberalizm

-

The Search for the Holy Grail in Modern Germany: An Interview with Clarissa Schnabel

-

Notes on Plato’s Gorgias, Part 12

1 comment

Contrast that with current generals and admirals who endorse black militants and tell white service members to get use to diversity.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.