The Dakota Territory’s Indian Wars During the Civil War

Part 1

Morris van de Camp

Little Crow was the leader of the Sioux during the 1862 Dakota War. He went to war because imprudent men had called him a coward. He had no grand strategy or clearly defined war aims. His actions initiated a series of Indian wars which would not end until 1890.

2,736 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here)

Wilmot Robertson wrote that “[t]he decline of the American Majority began with the political and military struggle between North and South.” This is indeed true. That conflict turned family members into bitter enemies and provided openings for non-American groups such as Jews and other foreign peoples to hijack the country.

But there was one part of that conflict which went against the trend: the conflict in the Dakota Territory. In the wild prairie of the United States’ north-central region, whites made considerable strides towards expanding their ethnostate (such as it was) by defeating a vicious non-white enemy while integrating former white enemies.

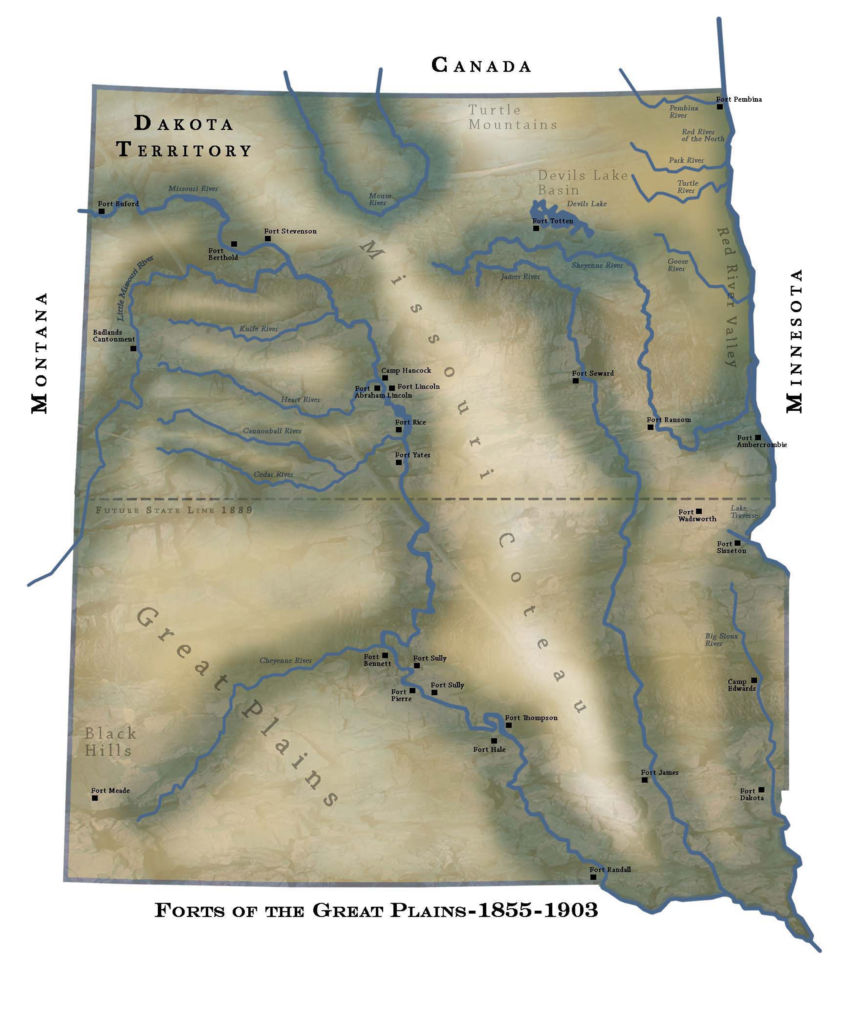

Fort Dilts, near what is now Rhame, North Dakota. The fort was built in a rush during the Dakota Campaign during the Civil War. It is named for Corporal Jefferson Dilts of the 1st Minnesota Cavalry, who was killed by Sioux Indians.

The 1862 Dakota War

During the US Civil War, Sioux Indians in Minnesota went to war with the white population despite the fact that they were drawing welfare and getting goods from the Americans. The conflict came to be called the 1862 Dakota War. As with all non-white-on-white wars, it became clear only in retrospect that the conflict had actually started before the whites realized it. The Sioux in Iowa had massacred whites in 1857 and escaped unharmed. Tensions only grew in the months that followed. In Minnesota during the summer of 1862, the Sioux began to routinely threaten their reservation’s white shopkeepers, putatively because they didn’t want to pay for the goods they’d purchased on credit. To make matters worse, the more experienced personnel working in the US Indian Agency who had been appointed by the Democrats had recently been swapped out for inexperienced men appointed by the then new Republican Party, which had just come to power in the 1860 election, when Abraham Lincoln became President. Thus, by the time the annuity payment that would have ended the crisis arrived, the war had already started.

After several braves killed a group of white settlers on August 17, 1862, they goaded their chief, Little Crow, into attacking the US government offices on their reservation. After this initial blitzkrieg, the Sioux proceeded to attack whites living near the reservation. White settlements that were home to immigrant communities from Norway, Sweden, France, and Germany were isolated, and thus especially vulnerable. The immigrant whites had less experience with Indians than the Anglo-Americans, and they didn’t have as many firearms.

Because the Civil War was pulling troops away from the Minnesota frontier so that they could fight in the East, the first batch of soldiers from Fort Ridgely to attempt to suppress the uprising was a company-sized unit that ended up facing an army of hundreds of Sioux warriors. When the company discovered the bodies of white settlers, they were themselves attacked and the survivors retreated to the fort. This led to a panic across western Minnesota. Whites abandoned their homes and farms and headed eastwards.

This conflict was especially ugly since there were so many whites within reach of the angry Sioux. Whites who were not killed outright were taken captive. Those wounded were left to die. Some captives were tortured to death; captured white women were gang raped. One female captive, Mary Schwandt, who was then 14, later recounted:

They then took me out [of a wagon] by force, to an unoccupied teepee . . . and perpetrated the most horrible and nameless outrages upon my person. These outrages were repeated at different times during my captivity.[1]

Brigadier General Henry Sibley was ordered to mobilize the 6th Minnesota Infantry, which was then being organized at Fort Snelling, and any other militia available to suppress the violent Sioux. Meanwhile the Sioux besieged New Ulm, Minnesota on August 19 and attacked Fort Ridgley a day later. One those at New Ulm who had arrived with a relief party during the siege was Dr. William Mayo. Dr. Mayo would go on to found the famous Mayo Clinic with his sons and several Roman Catholic nuns.

You can buy Tito Perdue’s The Gizmo here.

The Sioux continued to press their attack, assaulting Fort Abercrombie on the Red River in Dakota Territory as well as several stagecoach stations. Unfortunately for the Indians, they’d gone to war with no clear political goals or plausible strategy for victory. It was a reckless endeavor, while the Union Army was recruiting or drafting thousands of white men and arming them. President Lincoln ordered Major General John Pope to take command of the overall campaign in the West, and he raised several regiments and sent them to Minnesota.

The decisive battle in the Dakota War occurred near Echo, Minnesota on September 23, 1862, and it is named for the largest lake in the area, Wood Lake. Sibley arrived at Wood Lake bringing several new regiments, the veteran 3rd Minnesota Infantry, and artillery. The troops and artillery were critical, but the ground for a decision victory was laid by Sibley’s letter-writing campaign to Little Crow, encouraging him to surrender. The letters were sent via captured Indians and half-breed intermediaries, and their contents became widely known among the Sioux. They effectively divided Little Crow’s warriors and their families along the lines of those who had always been against the war and those for it. It had been a mistake for him to go to war rather than stand up to a mob of angry braves.

Most of Little Crow’s followers surrendered after the Battle of Wood Lake, but he recruited a smaller number of warriors to continue the war, going into armed exile in the Dakota Territory, with occasional retreats into Canada. The Indians who surrendered released their white captives and were then moved to Fort Snelling. On the way to the fort they were accosted by white mobs, often led by women, and some were killed. Surrendered Indians who had committed rape and murder were given a military trial, after which many were sentenced to death after only five minutes. President Lincoln commuted most of the sentences, but 38 Indians were hanged — one by mistake.

General Sibley was viciously criticized throughout the campaign, but he ignored it and continued to do his duty with ruthless efficiency. All leaders in a difficult situation such as a war will be subjected to criticism; the important thing is to continue to pursue mission accomplishment.

The Dakota Campaign

Minnesota’s whites were angry and wanted revenge. There were also suspicions that the Confederate government had encouraged the uprising. It hadn’t organized the attack, but such a suspicion was not unfounded. Several tribes took sides in either Union and Confederate factions, and nasty fighting followed. It was also possible that either the Confederates or the British might send the Sioux arms and other supplies through their agents in Canada.

Major General Pope therefore determined that it was necessary to send an expedition into the Dakota Territory to resolve the situation. Little Crow did not participate in the renewed fighting, however, as he was killed by a white hunter on the same day as Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863.

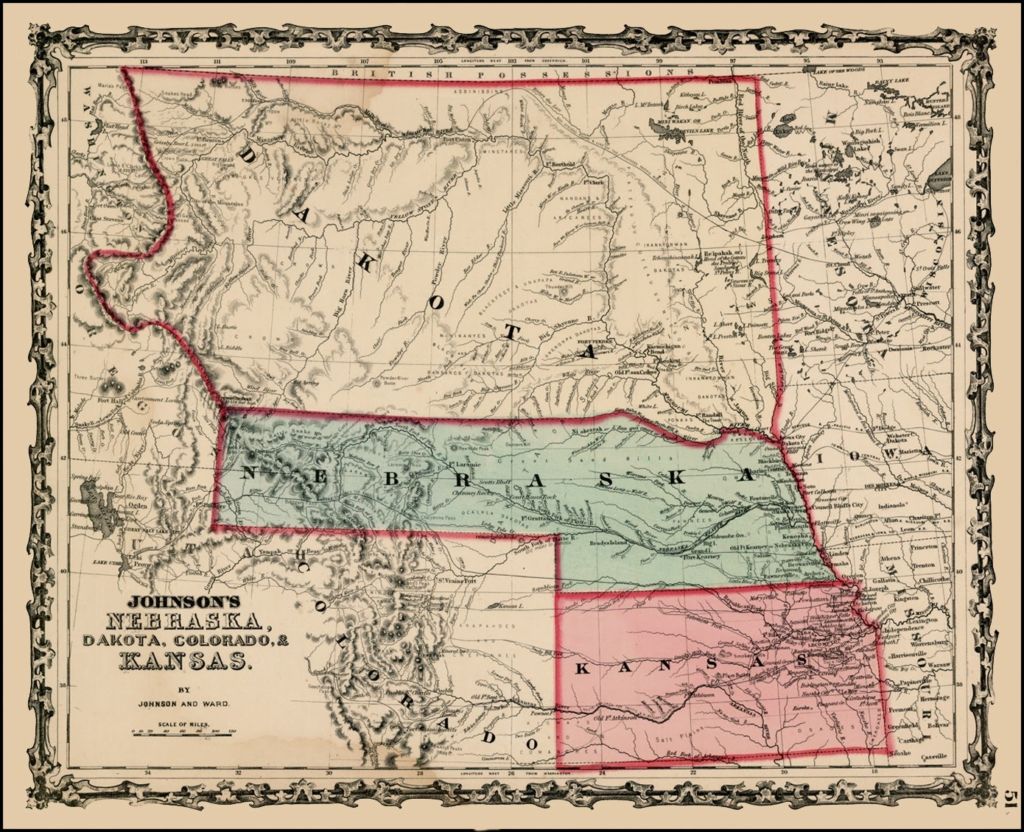

In late June of 1863, the Union Army invaded the Dakota Territory with a force consisting of two columns. The first, under Sibley, set out from Fort Abercrombie on the Red River’s west bank. The second, under Brigadier Alfred Sully, departed from Sioux City, Iowa. The combined force consisted of men raised from Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa. A battalion of cavalry was raised in the Dakota Territory itself, mostly from the white, American Majority settlers from the southeast corner of what is now South Dakota.

The location of Civil War battles where there are now state or national parks. It does not show all the battlefields, however. Iowans had to contend with a Confederate attack on Croton (not shown). Iowa’s deadliest enemy was not the Confederate whites to the south, but the Sioux to the north. In the Dakota Territory, most of the battles took place in what is now North Dakota.

Sibley’s men did most of the fighting, battling the Sioux three times before the Indians were able to successfully slip away across the Missouri River, not far from what is now Bismarck, North Dakota. Sully encountered Indians as well, but not all were hostile.

The march of Sibley’s column to the Missouri was as much an undertaking as the battles themselves, as the Dakota Territory was struck with a drought that summer. The grass was therefore thin and short, and water was scarce. To keep their draft animals alive, the soldiers had to go out with scythes and bring in grass every time they stopped. The columns began their marches at 2 AM due to the heat, and halted around midday or where there was water.

You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s Western Civilization Bites Back here.

There were other challenges as well. The 10th Minnesota Infantry had to receive additional training during the campaign given that they’d been so hastily recruited. Sibley continued his letter-writing as well; in one instance, his men captured the son of a Chief and then released him so that he could carry a letter of friendship back to his father.

On July 31, 1863, Sibley received orders to return to Minnesota, as no more supplies could be sent forward. This meant that following the Indians across the Missouri was no longer feasible. The Sioux were able to cross the river in part because Sully’s column, which was moving up from the south, was unable to link up with Sibley’s and thereby cut off the Indians’ retreat. Sully’s column depended on river boats, but the river had become too shallow for them due to the drought. They did finally catch up with a large Sioux band on September 3, 1863, however, resulting in the Battle of Whitestone Hill. Sully’s force was victorious.

More recently, scholars and anti-white activists have argued that the Indians targeted in the 1863 campaign were innocent of any wrongdoing. The situation was such that any Indian band could be whipped up into a fury and massacre innocent white Americans, however, even if those Indians had signed a peace treaty, were given annuities, and had been given a reservation on some of North America’s best farmland. Thus, military force was necessary.

The campaign in the Dakota Territory resumed the next summer, but only Sully was in overall command in the field. His army consisted almost entirely of mounted troops. The entire 8th Minnesota Infantry, for example, rode on Canadian ponies. In contrast with the Dakota War two years earlier, now there were more than 2,000 soldiers dispatched from Fort Ridgley. Another force of similar size set out from Sioux City, Iowa. The column from Minnesota was filled with hostility towards the Indians, and they were responsible for the vicious actions hinted at in movies such as The Searchers. The first Indians the Minnesota soldiers encountered were already dead and buried, but the men dug them up and mutilated their bodies anyway.

Sully’s 1864 campaign had several objectives: decisively defeat the Sioux, continue to build forts along the Missouri, and protect emigrant trains mostly consisting of miners. The action began on June 28, 1864. At the Little Cheyenne River, an officer collecting insect specimens was killed by a party of Sioux. Sully ordered Captain Nelson Miner and his troops, Company A of the 1st Dakota Cavalry, to pursue and kill the Indians. They did. Sully then ordered the heads of the slain Indians to be put on stakes atop a high hill to serve as a warning. This enraged the Indians and hardened their resistance. Sibley’s letter-writing campaign had been a better strategy.

Shortly after this incident, Sully established Fort Rice. While building the post, Sully met with an emigrant train that had been attacked by Indians. The Indians had feigned friendship, asked for food, and then attacked the whites. These emigrants remained with Sully throughout most of the campaign before heading for Idaho’s gold fields on their own once the column reached what is now eastern Montana.

Sully then received intelligence that a large camp of Sioux was nearby. He marched out with his army to meet them on July 19, 1864. The Sioux and Americans met at Killdeer Mountain on July 28. Although the Indians were prepared for Sully, the Americans nevertheless triumphed, the key being artillery; the Sioux were overwhelmed by the superior firepower.

After Killdeer Mountain, the Sioux then retreated to the Badlands of what is now North Dakota. This region consists of bluffs and broken terrain through which the Little Missouri River flows. Sully called the place “Hell burned out.” It was extremely hot, and most of the grass had been eaten by grasshoppers. His men ended up walking alongside their hungry horses rather than tiring them by riding throughout most of the expedition. The Sioux attacked the column in several hit-and-run engagements, but were always driven off by artillery fire and superior numbers. Sully eventually made it to the Yellowstone River in eastern Montana, but turned back given that his supplies were nearly exhausted. The column had several more minor run-ins with the Sioux on their return journey to Fort Rice, but no decisive battle that could have ended the conflict were fought.

After reaching Fort Rice on September 8, 1864, Sully received word that an emigrant train had come under attack just south of the Badlands. This train was under the command of Captain Fisk, a quartermaster. Six days earlier the Sioux, including Sitting Bull, attacked the emigrants with a large force while the whites were distracted by recovering an overturned wagon. Fisk’s command circled their wagons, built a fort made of sod, and waited for the rescue party from Fort Rice. Captain Fisk named their makeshift castle Fort Dilts after Corporal Jefferson Dilts, who had been killed leading a counterattack against the Sioux in the battle’s initial moments. Corporal Dilts managed to kill several Indians and even wound Sitting Bull before being mortally wounded.

The key to holding the Dakota Territory was to develop forts along the riverways. The forts were supplied by steamboats, but the waterways were impassable in the winter, when the rivers froze over.

As winter approached, the Union soldiers began to move into winter quarters in the various forts across the region. The Sioux chiefs sent messages to the Americans offering peace. This was a common Indian tactic: to feign peacefulness during the winter in order to draw supplies from the Indian Agency or a military fort, then resume fighting during the summer. In the late autumn of 1864, the Sioux chiefs made a truce more attractive by offering to return Fanny Kelly, a white captive, in exchange for peace. The Kelly exchange was carried out at old Fort Sully, near what is now Pierre, South Dakota. Upon her release, Kelly said:

I had borne grief and terror and privation; but the delight of being once more amongst my own people was so overpowering that I almost lost the power of speech, or emotion, and when I faintly murmured, “Am I free, indeed free?” Captain Logan’s tears answered me as well as his scarcely uttered “Yes,” for he realized what freedom meant to one whom had tasted the bitterness of bondage and despair.[2]

Kelly had made it back to white civilization just in the nick of time. Little Crow’s uprising in 1862 turned out to the be only the start of hostilities that ended up spreading across the Great Plains and continuing for nearly three more decades. In Colorado the 1st and 3rd Colorado Cavalry regiments had defeated an Indian force led by Black Kettle at Sand Creek; if word of this had reached the Sioux before Kelly was returned, it is likely that she would have been tortured to death.

The Union Army’s two campaigns ended the Indian threat in the Minnesota frontier, but they were not decisive victories. Nevertheless, the series of forts that had been established along the Missouri River at the time, especially Fort Rice, ended up being the first step toward bringing white civilization to the region and ultimately helped to reunite the North and South.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] Paul Williams, The Dakota Conflict and Its Leaders, 1862-1865: Little Crow, Henry Sibley and Alfred Sully (Jefferson, N. C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2020), 52.

[2] Ibid., 210.

The%20Dakota%20Territoryand%238217%3Bs%20Indian%20Wars%20During%20the%20Civil%20War%0APart%201%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Introduction to Mihai Eminescu’s Old Icons, New Icons

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

1 comment

An excellent book on this subject is Lincoln and the Sioux Uprising of 1862 by Hank H. Cox. A few tidbits concerning the behavior of the Indians, the soldiers, and the homesteaders:.

page 51: One Indian, Carrothers reported, seized “ a sweet and pretty child of two, and beat her savagely over the head with a violin case, smashing her head horribly out of shape. Then he took her by her feet and dashed her brains out against the wheel of the wagon, spattering her mother with blood and brains. Another fiend took the nine months old boy, hacked off his limbs with a tomahawk, and threw the pieces at the mother. Then they made a big fire and tossed featherbed, woman and mangled children into the flames.

Some of the worst atrocities were committed by followers of Red Middle Voice who appears to have been something of a maniac. His warriors took perverse pleasure in hacking off the limbs of victims before they died. They nailed children to doors, running spikes through their arms and legs and swinging them back and forth until they expired. At one cabin they killed a homesteader and his two sons in a field and murdered his wife and two youngest children in their house. Their thirteen year old daughter was stripped naked and raped by twelve Indians.

page 148: Mankato was killed by a cannonball, which witnesses say he refused to dodge. His body was taken from the field, but another fourteen or fifteen dead warriors lay scattered on the ground, and most of them were scalped by the soldiers. [General] Sibley was offended by this and threatened dire repercussions if any more scalping occurred. “The bodies of the dead,” he said, “even of a savage enemy shall not be subjected to indignities by civilized and Christian men.” Supposedly this work was done by the Renville Rangers, who were half-breeds and thus at least partly heir to Indian battle traditions.

And even in the twentieth century, there was this incident, described on page 199:

In June 1919 Edward Gleek, living near New Ulm, cut down a large white oak tree that broke in two as it fell. Inside, he found the mummified corpse of, according to his journal, Jean La Rue. When the first soldiers arrived in New Ulm in 1862, they had fired their rifles in an apparent act of exuberance that terrified many residents who feared it was a Sioux attack. La Rue grabbed his rifle and other belongings and ran to a hollow tree to hide. Apparently he got wedged in, was unable to extricate himself, and his cries for help went unheard. With his body were found his rifle, bullet pouch, powder horn and $783.50, a not inconsiderable sum in those days. He had written: “Can not get out surely must die. If ever found, send me and all my money to my mother, Suzanne La Rue, near Tarascan, in the province of Bouches Du Rhone, France.” Efforts to contact his family were futile.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.