Robert Rutherford McCormick,

Midwestern Man of the Right

Part 2

Morris van de Camp

1,945 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

Military mid-level management

McCormick’s military career couldn’t be replicated today. In today’s United States military, either a college student is recruited to take classes in military leadership, or an enlisted man is selected to attend officer candidate school. Then, after 12 years of service, he may be promoted to Major. At no time during those 12 years can the soldier leave the service, and he must serve in a series of specific jobs. Any deviation from the norm means no promotion.

Many people enlist or are commissioned with the idea of gaining military experience prior to going into another field. As a result, talented people leave quickly. In McCormick’s case, the military was able to recruit a man who was accomplished before he entered the service. Today, it is impossible to recruit a mid-level officer from the civilian workforce. Aside from the obvious diversity problems that would entail, the inability to fully utilize America’s human resources is undoubtedly in part why the US continues to lose wars.

After Cantigny (1920-1933)

McCormick’s rivals attempted to “swiftboat” his military service, but they were unsuccessful. Too many people had seen McCormick at the front, doing his duty. McCormick would come to view the Battle of Cantigny as the most important event of his life. He displayed framed maps and paperwork from the war in his office and named his farm in Wheaton, Illinois “Cantigny.”

With the war behind him, McCormick focused on expanding his business empire. He improved his paper supply chain, increased the efficiency of his press by purchasing new printing machines, and increased his circulation. His cousin Joseph Medill Patterson, who had been a Captain in the war, greatly aided him in getting new subscribers, creating the comic strips Gasoline Alley and Dick Tracy.

Until Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s election in 1933, McCormick was involved in events that were important in their place and time but which seem trivial from today’s perspective: He was a bitter enemy of Chicago’s four-term Mayor William “Big Bill” Thompson, he met with Al Capone during a threatened strike, and later colluded with the US government to bring Capone down. McCormick likewise opposed Prohibition and was involved in bankrolling court cases that favored freedom of the press as he saw it.

After 1933

The Chicago Tribune was a newspaper with a political agenda. It disliked what McCormick disliked, including liberals, the League of Nations, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, England, Henry Ford, New York, and the South. McCormick’s hostility towards England and the South were prejudices that Midwesterners retained from the War of 1812 and the Civil War, respectively. McCormick’s dislike of New York and Henry Ford were due to personal beefs, but his dislike of FDR and the League of Nations were serious philosophical stances that are relevant for Americans today.

You can buy Fenek Solère’s novel Rising here

Roosevelt supported massive government intervention in the economy. McCormick opposed most of these programs, apart from the Civilian Conservation Corps, but he was unable to do anything about them. It wouldn’t be until the stagflation of the Carter administration that New Deal-style economic management began to be abandoned, and was finally completely dismantled by the Clinton administration.

Starting in 1934, McCormick attempted to simplify the spelling of English words. This effort didn’t broadly catch on across the Anglosphere, but some of McCormick’s unique spellings made it into the Unabomber’s manifesto.

When the Second World War broke out, McCormick threw all his energy into preventing American involvement. He was especially suspicious of British charm offensives in the American media. He reminded his reporters in England that “no Chicago Tribune reporter would get a tablet at Westminster Abby.” Tribune reporters were expected to remain neutral.

McCormick was well-read and aware of the problems in Europe that had led to the war. He recognized that the economically-viable states there ethnically unstable, and the ethnically viable ones were not economically viable. He was also aware of the Jewish Question, but he had a tragically naïve view of Jews. His biographer Richard Norton Smith wrote:

Within days of Hitler’s designation as chancellor in January 1933, the Tribune had denounced Nazi persecution of German Jews as a hateful reminder of the Dark Ages. Yet when pressed by his editorial writers to strike fresh blows at the regime, McCormick held back. Claiming to be “very much concerned” about anti-Semitism in the United States, he feared the scapegoating of Jews. . . . Indeed, said McCormick, “I don’t see how the next election can avoid the Hebrew issue. With governors of the two principle states both Democrats and both Jews, with two judges of the [SCOTUS] both Democrats and both Jews, political expediency will point the Republicans towards a Ku Klux movement.” The less drum-beating by the press, he hinted broadly, the less chance that America would succumb to the racial and religious divisions then poisoning Europe.[1]

McCormick should have pointed out the fact that Jews are a separate nation only loyal themselves, and that there is no way for any nation, even the US, to avoid having to eventually deal with them. McCormick was considered to be on the far Right at the time, but the statement above shows just how limited the range of political debate was in 1930s America.

McCormick supported the America First anti-interventionist movement wholeheartedly. McCormick worked with Charles A. Lindbergh and fellow war veteran Brigadier General Robert Wood, an executive at the Sears-Roebuck Company, to organize rallies, pressure politicians, and otherwise keep America out of the fighting.

Just before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Tribune published the details of a secret war plan that had developed by the Roosevelt administration for an attack on Germany by 1943. It has never been determined who leaked the plan, but it might have been FDR himself, given that he was in the midst of an information war aimed at goading Germany into declaring war on the United States – which finally came on December 11, 1941. This freed the Roosevelt administration to openly align their efforts with the British and carry out a “Germany First” war strategy, meaning that America’s resources were to be sent to Europe first and the Pacific second — despite the fact that it was Japan that had attacked the US.

FDR moved to counter McCormick as much as he could. A Chicago Tribune reporter was in fact subjected to verbal abuse by the President in the Oval Office for a quarter of an hour in the wake of Pearl Harbor. FDR let it be known that he felt McCormick should be blamed for America’s “unpreparedness.” FDR also attempted to squeeze the Chicago Tribune by rationing its supply of paper and by having his allies prop up rival papers in Chicago.

McCormick’s biggest conflict with the Roosevelt administration came after the Battle of Midway in June 1942. The Chicago Tribune had an embedded reporter with the US Navy who suggested in his articles that the Americans had possibly won the battle because they had broken the Japanese Navy’s code. This was in fact true, but was of course classified. The Roosevelt administration launched an investigation, but when it became clear that the Japanese still hadn’t caught on to the fact that their code was broken, they backed off.

McCormick continued to criticize Roosevelt throughout the war, but supported the war effort in important ways. His employees who joined the military got their jobs back when they returned. He also cooperated with the government to bug the offices of the Japanese consulate in Chicago, which was located in one of the buildings that he owned.

Once war arrived, the America First movement fell apart — to a degree. McCormick pointed out that FDR had partly goaded the Japanese into attacking. Many of his suggestions, such as putting American bases on British islands in the West Indies, were carried out. McCormick’s isolationism, along with his anti-British attitudes, were disseminated in the press and caused the Roosevelt administration to drive a hard bargain when the British came asking for aid. After the war, the Americans turned off their Lend-Lease Aid so fast that the British faced bankruptcy in 1946.

McCormick supported the Republican Party, but the party at the time was fielding poor candidates who always lost. He blamed much of the problem with the internationalists and financiers on the East Coast.

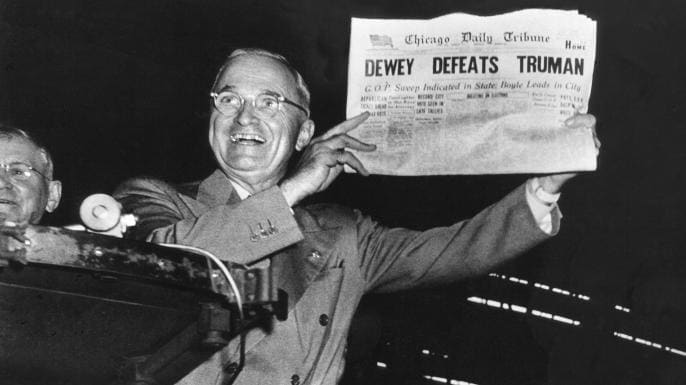

This iconic image is today seen an example of the unreliability polling, but at the time Truman was displaying the incorrect headline to humiliate Robert McCormick.

The 1950s

When the Korean War broke out, McCormick’s isolationist views found few supporters. He shifted to pointing out the problem of calling the Korean War a “police action” rather than a war, and he was frustrated with Congress for being left out of the decision to go to war in the first place. He also supported Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, who was the furthest to the Right the Republicans had to offer at the time, for President in 1952. Dwight Eisenhower ended up getting the nomination instead.

McCormick continued to work with other members of his family to advance the Republicans’ prospects across the country, especially in Maryland, but in his 70s he was in poor shape. His liver was weak after years of drinking, and he had heart problems. His family members recognized that he was declining, and they began angling for their roles in Chicago Tribune’s empire after he passed away. When he finally did pass away in 1955 he was buried in his war uniform.

Postscript

The 1990s witnessed a push for American military involvement in nearly every trouble spot on the planet. The biggest advocate for this was a Jew of immigrant stock, Madeleine Albright, who was Secretary of State in the Clinton administration. This Israel-first, internationalist Jew rose to such a high position in part because she married the grandson of Captain Joseph Medill Patterson — Robert McCormick’s first cousin. The organized Jewish community has a long history of gaining power by marrying off their daughters to prominent members of their host society. It is therefore up to the host society to avoid these manipulative matches.

Between a prophet and an advisor

There is a memorial to the Americans who died fighting on the Allied side of the First World War in Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London. The gratitude behind it was undoubtedly genuine, but one can’t help speculating that McCormick’s pointed remarks about “not getting a tablet at Westminster Abby” was part of the motivation for building a memorial in such a prominent place. McCormick was so influential that his political enemies responded to his criticisms.

McCormick died when American isolationism was at its nadir. In 1950, American economic power, military capability, and diplomatic savvy was at its height. Generations of Americans believed that had spent his life arguing for a worldview that had passed from the scene. But he recognized very early on that America’s international engagements had a limit. Today, Americans are at the center of an overstretched empire whose primary export is sexual perversion. McCormick was on to something.

McCormick was not a prophet who spoke nothing but the truth, and he didn’t foresee all the problems that were to overtake post-war America. He was also not an advisor to the powerful in the strict sense, but his political rivals took ideas from him and then went their own way. He was therefore something between an advisor and a prophet. But whatever we want to call him, McCormick made a difference.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Note

[1] Richard Norton Smith, The Colonel: The Life and Legend of Robert R. McCormick, Indomitable Editor of the Chicago Tribune (New York: Houghton Mifflin,1997), pp. 324-5.

Robert%20Rutherford%20McCormick%2C%0AMidwestern%20Man%20of%20the%20Right%0APart%202%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

1 comment

Very good, Brother van de Camp. Not much more I could add, beyond the mechanical polo-practice horse, which I still need to see a picture of!

My piece on Cousin Cissy is coming up shortly…

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.