Mountains of the Mind: Dürer, Disenchantment, & the Urge to Ascend

Tobias Langdon

Lived with for millennia, first climbed in 1865: the Matterhorn

2,657 words

“I was using the mountain to measure myself. The mountain is the means, the man is the end.” — Walter Bonatti (1930-2011)

People who climb mountains are like people who ride motorbikes or take illegal drugs. They tend to have a lot of friends who die young — or they die young themselves. But climbing mountains isn’t about desiring death. It’s about defying death. Climbers are in search of peak experiences in more ways than one. They seek moments of emotional and spiritual exaltation, and such moments are most surely found on the edge between life and death, when you gamble with your own blood and bones as a stake.

To God’s greater glory

But people haven’t always gambled like that. Human beings have lived with mountains for many thousands of years, although the true urge to climb them, to claim them as prizes in a game of high risk and high skill, appeared only in the past couple of centuries. And only in a small part of the world: the pale, stale region known as Europe. Like science, technology, and other central aspects of the modern world, mountaineering was a white male invention. It was part of an explosion of white male exploration, adventure, and ingenuity, and it can only be properly analyzed and understood in that wider historical context. For example, I would claim that mountaineering was, in its way, as much a fruit of Protestantism as the King James Bible or the Industrial Revolution.

Under Catholicism, what might be called the urge to ascend had produced the glories of Gothic architecture, which soared heavenward in exaltation not of individual architects or their royal sponsors, but of the Church as institution and its Heavenly King. In the Middle Ages artists and craftsmen labored ad maiorem gloriam Dei, “to the greater glory of God,” not to the greater glory of themselves. In some cases we don’t even know the true names of those supremely talented architects, painters, and sculptors who have come down to history simply as the Master of 1342, the Master of Alkmaar, the Master of Heiligenkreuz, or the Master of the Graudenz Altarpiece. That’s why one reason that the German genius Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) is such a significant figure in the history of European art and culture. We know Dürer’s name not simply because he was a genius who deserved to be famous, but because he himself was determined that we should know his name.

Great hair, great heir

And that we should know his image. Dürer was a Türöffner, a door-opener, at the wall that separated the Middle Ages from modernity. He was a genius who knew himself to be a genius, and in the new, proto-Protestant culture he was happy to glory in that fact. That’s part of why he painted so many versions of something that no pious medieval artist would ever have dreamed of painting: a self-portrait. Earlier artists had included themselves in their art, but they hadn’t filled the frame with themselves. Dürer did fill frames with himself, staring out at the world with justified pride — and perhaps with arrogance and narcissism, too. Dürer’s self-portraits in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are far removed in time from the photographic selfies of the twenty-first century. But are they far removed in psychology?

Great art, great hair: Dürer’s self-portrait of 1500

Perhaps not. One thing that is certainly very different between Dürer’s self-portraits and the selfies of today is the skill and effort required to create them. What required genius and long hours of labor back then requires only a finger and a moment now. So Dürer’s legacy of self-exaltation may have run truer as it ran wider: away from art and imagery into self-exaltation that continued to demand skill and effort. Mountaineers are Dürer’s heirs in a way that selfie-takers aren’t. But Dürer had a musical heir, too: Beethoven broke with the geniuses of the Baroque rather as Dürer broke with the geniuses of the Middle Ages. Men like Bach, Mozart, and Vivaldi were what you might call humble geniuses, content to subordinate their astonishing talent to the service of religion and musical tradition, to enrich the ear and delight the soul with harmony, beauty, and elegance.

A God-shaped gap

Beethoven was different: He was a thunderclap in musical history heralding a storm of innovation and invention — and of egotism, some would say. “Beethoven was a narcissistic hooligan,” Dylan Evans once wrote in a very interesting article at the Guardian. How so? Beethoven “diverted music from elegant universality into tortured self-obsession.” Evans makes an excellent case, but less certain than his condemnation of Beethoven is his categorization. Beethoven was indeed something new. I would suggest that, like Dürer’s, his ego was expanding into a God-shaped gap: The Church was retreating and artists were advancing into its abandoned territory; artists and others, because I would identify the same or similar cultural and psychological forces at work in the voyages of Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521), Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), and Francis Drake (1540-1596). They were white men who braved the wide, wild, and often deadly waters of the Atlantic and Pacific.

Their voyages’ psychological importance was clearly seen in their own era: the Protestant philosopher and propagandist of science Francis Bacon (1561-1626) took them as a metaphor in the frontispiece of his book Novum Organum (1620), which “shows a ship sailing in through the pillars of Hercules (identified with the strait between Gibraltar and North Africa — the opening from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic) after exploring an unknown world.” That was the white male urge to explore, which became an urge to ascend in the mountaineers of the nineteenth century. After all, where else was there to go by then? Exploration in two dimensions, over the surface of the Earth and its oceans, was clearly nearing its end. Africa’s outlines were known, and although there was much work still to do between the outlines for men like Sir Richard Burton (1821-90) and Henry Livingstone (1813-73), that work was both too much and too little for some of their contemporaries.

Drained of mystery and meaning

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here.

African exploration was too much in that it demanded months or years of effort amid heat, disease, and danger; and was too little in that exploration was an old activity by then, crowded with famous names and feats. At least, exploration in two dimensions was old hat by then: north and south, east and west. But what about the third dimension, up and down? What about mountains and caves and the world beneath the waves? Under Catholicism, the world had been psychologically flat: God gazed from on high upon men far below, who felt crushed and constrained by the weight of His majesty and might. Gothic cathedrals were built to exalt the Godly heights, not to intrude there or allow man to inhabit those heights. But as Protestantism replaced the institution with the individual, and the science spawned by Protestantism began to drain divinity and agency from existence, the world became psychologically three-dimensional. The aspirations, and egos, of white men sprang skyward; and sooner or later their bodies would follow their minds. They would want to confront and conquer the stone titans of the Alps.

And if, as I remarked earlier, mountaineering was as much a fruit of Protestantism as the King James Bible, it sprang from more barren soil. I would claim that an essential factor in the rise of mountaineering was what the German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1930) called die Entzauberung der Welt: “the disenchantment of the world” that accompanied the Industrial Revolution and the rise of modern science. While Asians continue to inhabit ein großer Zaubergarten, “a great enchanted garden,” Europeans progressively banished God and spirit from their understanding of the world, draining it of mystery and meaning — but also of menace. In ancient and medieval times, mountains were seen as divine realms, forbidden to mortal trespass, or as the abode of demons and dragons, malicious beings that would punish those who intruded there. With disenchantment, divinity and demons disappeared: Mountains became part of comprehensible and conquerable nature, not of capricious and unchallengeable supernature.

A permanent truth

This confluence of cultural and psychological factors explains why, in the nineteenth century, white men began to seek peak experiences in the Alps. However, you could say that Alpinism began not with a bang but a Whymper. The most famous of the early climbs was led by an English mountaineer and explorer named Edward Whymper (1840-1911). It was famous because it combined great triumph with greater tragedy: Whymper’s seven-strong party made the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865, but one man slipped on the descent and dragged three others to their deaths with him. If a rope hadn’t snapped, the entire party might have perished.

The tragedy was a stark illustration of a permanent truth: to climb mountains, you have to defy death. Skill is not enough; you also need luck. And because you need luck, you need courage. The pioneers of the nineteenth century, with their primitive equipment and still evolving techniques, were very brave men. But they weren’t simply brave men: They were brave white men drawn, at their best and most successful, from a particular set of nations and their diasporas.

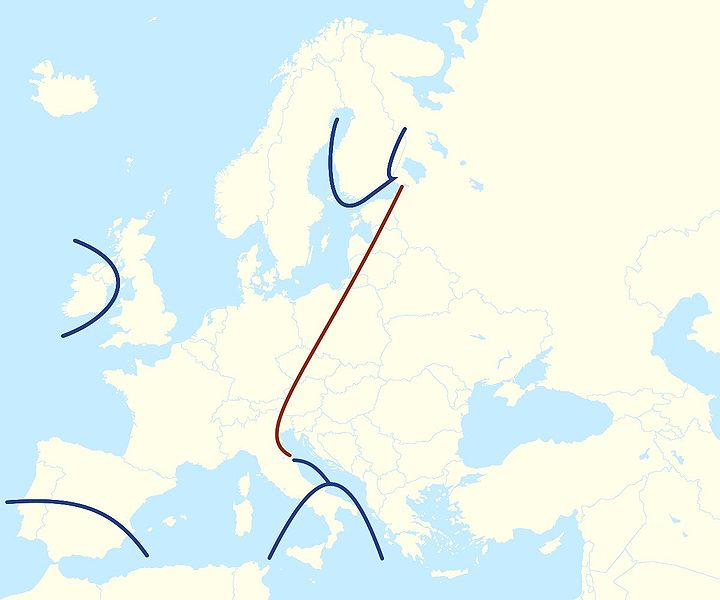

The greatest mountaineers overwhelmingly came, and come, from west of the Hajnal Line, from the special area of Europe marked by later marriage, greater individualism, and better cooperation between strangers. Speakers of English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, and Polish have always been heavily over-represented among the great names of mountaineering. One of those names might seem unexpected, but was in fact highly appropriate: Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), perhaps the most interesting and unusual mountaineer who ever lived — and also perhaps an embodiment of the themes of this article.

“Respect due to the cloth”

In 1902 Crowley was part of an expedition to the notorious Himalayan mountain K2 led by his great friend and mentor Oscar Eckenstein (1859-1921), an expert mountaineer who was half-Jewish and half-English. The expedition dissolved into rancor and recrimination, leaving Crowley’s respect for Eckenstein undiminished but further strengthening his own reputation as someone who was mad, bad, and dangerous to know. Earlier in his mountaineering career, Crowley had waged part of his war on Christianity in the Alps. Staying at the Swiss village of Arolla in 1897, he had secretly taught a schoolgirl to climb a large and difficult boulder in order “to have some fun” with non-climbers. When the girl displayed her apparently uncoached skill before a large crowd, Crowley had his chance for fun with a chaplain:

People began to urge the chaplain to try his hand. He didn’t like it at all; but he came to me and said he would go if I would be very careful to manage the rope so that he did not look ridiculous, because of the respect due to his cloth. I promised him that I would attend to the matter with the utmost conscientiousness. I admitted that I had purposely made fun of some of the others, but that in his case I would tie the rope properly; not under his arms but just above the hips.

Having thus arranged for the respect due to his cloth, I went to the top of the rock and sat sufficiently far back to be unable to see what was happening on the face. When he came off, as the rope was fastened so low, he turned upside down. I pretended to misunderstand and jerked him up and down for several minutes before finally hauling him up, purple in the face and covered with scratches. I had not failed in the respect due to his cloth.

–The Confessions of Aleister Crowley (1929), Chapter 15

That could serve as a metaphor for mountaineering as a whole: the sport, or more-than-sport, began in earnest only after Europeans lost their respect for the Church and began to seek literal self-exaltation on the heights. Rebel Protestants from Britain, Crowley amongst them, were pioneers among the pioneers, making some notable first climbs in the Alps and founding the first Alpine Club in London in 1857.

First wall, then war

And once a mountain has been climbed for the first time, the search is on for new and harder routes under harsher conditions. By some routes, the Austrian mountain known as the Eiger, or Ogre, is an easy climb; by the Nordwand or Mordwand, the “murder-wall” or freezing and avalanche-swept north face, it is extremely difficult and dangerous. The Mordwand did indeed murder those who first attempted it. I can see another metaphor in the young German-speakers who died in the 1930s trying to climb the Mordwand for the greater glory of Germany. Eventually, in 1938, a combined German-Austrian party conquered the north face, to the delight and congratulations of Hitler. Soon millions more German-speakers would face the Mordwand of the Second World War, but there would be no successful ascent there.

After the war, however, German-speakers continued to excel in the mountains. Reinhold Messner (born 1944) comes from German-speaking north Italy and was inspired by the Austrian great Hermann Buhl (1924-57) to climb the world’s 14 mountains above 8,000 meters, all of which are in the Himalayas. In descending order of height, but not difficulty, they are Everest, K2, Kangchenjunga, Lhotse, Makalu, Cho Oyu, Dhaulagiri I, Manaslu, Nanga Parbat, Annapurna I, Gasherbrum I, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum II, and Shishapangma. But why was it a white male who performed that astonishing feat? The Himalayas are home to races, like the Nepalis and Tibetans, who have evolved over millennia to be adapted to high altitudes and thin air. Indeed, the Tibetans acquired useful genes from a population of Denisovans, a now extinct human species, who may have lived in the Himalayas for hundreds of thousands of years. But Nepalis and Tibetans did not feel the urge to ascend; they lived with mountains without seeking to climb them. It was European outsiders, adapted to low altitudes and thick air, who arrived to conquer the giants of the Himalayas.

Foam on a genetic ocean

Some of those outsiders triumphed, some succumbed to tragedy. Some did both. The awesome south face of Annapurna, which the English mountaineer Chris Bonington likened to four Alpine faces piled on top of each other, was conquered under his leadership by two climbing greats: the squat northern Englishman Don Whillans (1933-85) and the slender Scotsman Dougal Haston (1940-77). Whillans was a close student of pint-glasses and Haston was a close student of Nietzsche, another hugely important figure in the transformation from the collectivism of the Middle Ages to the individualism of the mountaineering ages.

Both Whillans and Haston died tragically young, but where Whillans drank himself to death, Haston died in a skiing accident. Mountains are dangerous in all manner of ways, but that is why human beings — and white men in particular — are drawn to them. By defying death amid the mountains, you make more of life. I’ve used cultural changes and sociology to explain the white male urge to ascend, but I’m sure that at least in part culture has been foam floating on a genetic ocean. Culture is easy to see, but it’s inadequate on its own as an explanation for the tides and tsunamis of history. Culture is profoundly influenced by genetics – and profoundly influences genetics in its turn.

Such co-evolution has taken unique, and uniquely important, forms among the white races of Europe. Mountaineering is only a small part of what white men have created, but mountaineering is excellent as a metaphor both for what white men have achieved and what they may achieve in future. The world is still three-dimensional and we still have the urge to ascend. We can climb out of the death-pit being dug for us by the Left and rise to surmount new challenges, conquering new heights both on the Earth and beyond it.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Mountains%20of%20the%20Mind%3A%20D%C3%BCrer%2C%20Disenchantment%2C%20and%23038%3B%20the%20Urge%20to%20Ascend

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

The Left-Hand Path: Hidden Nexus of Politics and Esotericism

-

La Dolce Vita

-

Renaissance and Reformation: The Verge by Patrick Wyman

-

The Kennedy Conspiracy

-

Alain de Benoist k populismu

-

What You Need to Know about the German New Right: An Interview with Martin Lichtmesz

-

The Worst Week Yet: April 21-27, 2024

-

Get to Know Your Friendly Neighborhood Habsburg

9 comments

It’s a shame how Catholicism kept the Greeks and Romans from mountaineering.

It’s also a shame how people don’t understand simple English: “In ancient and medieval times, mountains were seen as divine realms, forbidden to mortal trespass, or as the abode of demons and dragons, malicious beings that would punish those who intruded there.”

Ever heard of Mount Olympus and who supposedly dwelt there? (Hint: It wasn’t the Pope or St Euphemia.) And was Catholicism ever strong among the Nepalese and Tibetans who declined to climb to the top of mountains? (Hint: No, it wasn’t.)

I am puzzled by your comment. At best I conclude that you entirely missed the irony of mine.

I have never heard the name of John Hajnal, but with the first look at the map with the line of his name I have got the feeling that the lands and peoples eastern of the line were under much more influence of horserider nations than the lands and peoples to the West of it. I mean here both Iranoaryan nomads like Scythians/Sakalar, Sarmatians and Alans, and Türkic nomads from Huns to the Tatars and Mongols (Kalmykians/Jungars).

***

It was a little strange for me, that the author in the article about mountains has not mention Julius Evola with a word.

I agree, see Meditations on The Peaks by Julius Evola , his ashes lie in crevice on Mount Rosa. He also devotes a chapter to skiing.

Mountain climbing is part of the Faustian impulse to strive towards infinite space. One of the great joys of mountain climbing/hiking is that it is inherently hierarchial, it is to do what many do not.

Very interesting article and many insights into White Man’s glorious past in this obituary.

But neither the genius of Dürer, Beethoven, Nietzsche, Heisenberg, nor the boldness of Columbus and Messner have saved the White Race from declining.

The winners are not to be found in painting, music, philosophy, science or mountain climbing, but in climbing the heights of

– finance

– banking

– media

– entertainment

and

– jurisprudence

… mountains of a different type, providing much more gratifying experiences to its narcissistic devotees.

They call it “Rainbow Valley” on Everest because of all the colored jackets on corpses too frozen and heavy to ever recover; a heady mix of experienced climbers, pretenders, and jackasses who had little to no experience with lesser peaks, but thought the world’s tallest mountain was a good bucket list item.

When discussing mountain climbing one must consider 1.) has the speaker or writer actually done it and 2.) are any death-defying kicks really the sane and responsible action, especially when one has a family depending on them? Few topics anger me more than mountain climbing, and explicitly for it’s supposed macho appeal. Meanwhile, one wrong move and you’re dead. And for what? Consider the concept of, “Accomplishment without purpose, or at least a reasonably justifiable one.”

I’ll concede fully that mountain climbing is both athletically and technically impressive. And I’ll also concede that it’s physically and spiritually transformative. But I would add that unless someone feels divinely inspired to do it, they have no business touching the ether of the gods.

To be clear, mountain climbers are generally not rescue workers, pararescue, rescue swimmers, smoke jumpers, police, firefighters, soldiers, fighter pilots, or paratroopers; in other words, people who regularly take death-defying risks for an understandable, and non-recreational purpose. The only people I can compare climbers to, are racecar drivers and motorcyclists. Even astronauts and test pilots can play the science and knowledge card. So like racecar drivers and motorcyclists, when climbers go splat, no one has the right to play the tragedy and surprise card: he or she knew the risks, and the worst happened.

“But climbing mountains isn’t about desiring death.”

Are you so sure about that? One or two climbers have had a death wish. Maybe not the rest, the true mountaineers, but some of them do. Two words: free climbers.

“One thing that is certainly very different between Dürer’s self-portraits and the selfies of today is the skill and effort required to create them. What required genius and long hours of labor back then requires only a finger and a moment now.”

I would argue great self-portraits also have far more feeling, emotion, and power in them, because the personal touch is self-explanatory.

“But as Protestantism replaced the institution with the individual, and the science spawned by Protestantism began to drain divinity and agency from existence, the world became psychologically three-dimensional.”

Interesting hypothesis. And probably broadly true. And along with mountain climbing, eventually came flight and space flight after the Reformation.

“Europeans progressively banished God and spirit from their understanding of the world, draining it of mystery and meaning — but also of menace.”

I like that last part, “also of menace.” People sometimes forget, or never knew, the sadism and intimidation of some aspects of Christianity as some chose to practice it. The loss of mystery and meaning, to the extent it connected to anything true, is indeed lamentable, but I have no issue jettisoning the rest. Good riddance.

“…the sport, or more-than-sport, began in earnest only after Europeans lost their respect for the Church and began to seek literal self-exaltation on the heights.”

Yes. I concur. Well said.

“…the young German-speakers who died in the 1930s trying to climb the Mordwand for the greater glory of Germany.”

For those interested, see the 2008 German film, “North Face” (Original title: Nordwand). I highly recommend it. And just for giggles I’ll throw in 1997’s, “Seven Years In Tibet” starring Brad Pitt as recalcitrant Austrian mountaineer, Heinrich Harrer, who was unconcerned with the Reich, but nevertheless climbed British India in this 1930s era of assertive Germanic supremacy.

“Soon millions more German-speakers would face the Mordwand of the Second World War, but there would be no successful ascent there.”

Cheeky. And aren’t we all more the worse for it. I’d rather be speaking German at this point.

“But why was it a white male who performed that astonishing feat? [Everest, K2, and the such]

Tenzing Norgay is his name. The Nepalese sherpa who summitted with Hillary on 29 May 1953. He also received the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal. Give the sherpa their due. And for good measure, consider the documentary, “Sherpa” (2015) to see just how much the climbing industry on Everest has changed since. The younger generation of guides are getting into fights on the mountain with wannabe yuppie Boomers and stockbrokers. It’s fantastic.

“Culture is profoundly influenced by genetics – and profoundly influences genetics in its turn.”

No disagreements here. Arguably your most profound statement in the article.

“…mountaineering is excellent as a metaphor both for what white men have achieved and what they may achieve in future.”

This is an excellent segueway into possible companion pieces on flight and space flight. I think we’d all like more Tobias Langdon musings on the white man’s exploration of the third dimension as a product of the Protestant Reformation. Please consider making this the first of a two or three-part series.

We in the Caucasus call our Mount Elbrus Myngy Taw, what means The Eternal Mountain. It is sacred for many peoples of the Caucasus, Iranoaryans and Türkic and others. And the name of mountain – Elbrus is the name of the mythic Nart prince. Nartlar or Nartla of the Nart sagas were mythic giants, brave and wise. Nart sagas are someway alike Nordic Edda.

Comments are closed.

If you have a Subscriber access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment