7,037 words

At the time of his death in 1962, modernist writer E. E. Cummings was the second most widely read poet in the United States after Robert Frost. William Carlos Williams ranked Cummings and Ezra Pound as “beyond doubt the two most distinguished” contemporary American poets. Pound titled his own global selection of poetry of various ages and cultures Confucius to Cummings: An Anthology of Poetry (1964).

A lifelong friend of Ezra Pound, Cummings has been called racist and anti-Semitic by the Establishment. Unlike many of his fellow modernists, he was unquestionably anti-Communist and a man of the Right.

Cummings wrote approximately 2,900 poems, two “nonfiction novels,” four plays, essays, and created numerous drawings and paintings.

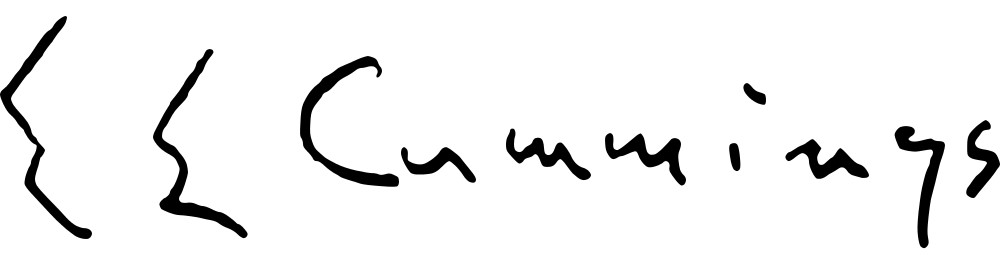

Edward Estlin Cummings’ name is often styled “e e cummings” in the mistaken belief that this is how it should be written. Publishers of his later books began lowercasing his name on their spines and covers in imitation of his poetry. He did not mind, but typically capitalized his own name and signature, though omitting the periods for his initials.

“E. E. Cummings” will be used here. The Complete Poems (1991) employs this style as, indeed, does my New Pocket Anthology of American Verse dating from 1955. The Complete Poems is as punctilious as Cummings himself was about the exact typographical reproduction of his work.

With regard to his famously idiosyncratic grammar, punctuation, and the distinctive appearance of his poetry and prose, he instructed his financial patron and Dial editor Scofield Thayer that there must be no changes in “spacing or punctuation in any particular,eg. if something begins with a small-letter,or a parenthesis,or has an uncapitalised personal pronoun,or if one line only in each stanza should be capitalised au commencement,or if small letter should follow a period.”

Cummings was called “Estlin” by friends and family.

“He was (like Frost) New England Yankee to the core,” Jonathan Yardley observed in a 2004 Washington Post book review. “Both his parents’ families had settled in the colonies long before the Revolution, Harvard was the family school, and Cummings was immersed in and faithful to Yankee tradition, as his poetry often reminds us.”

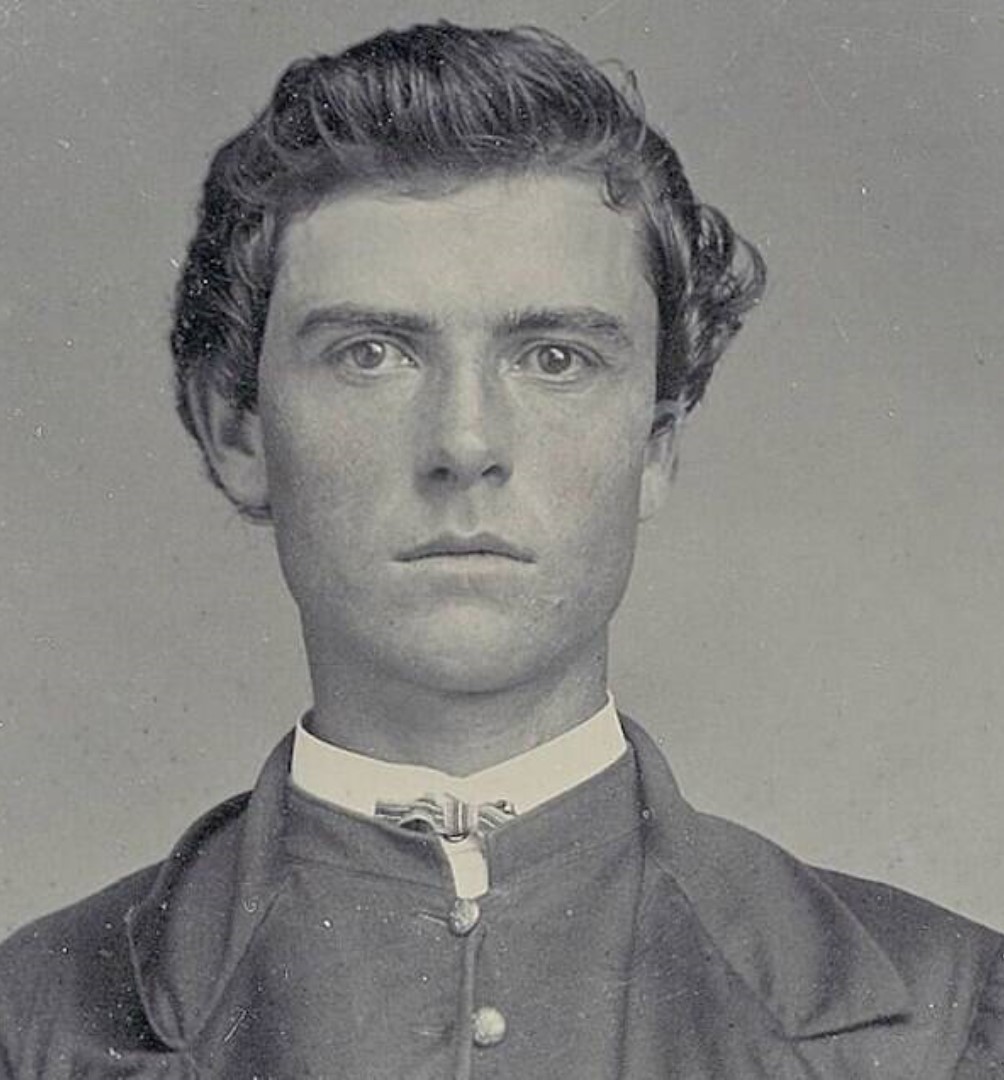

Described as tall and blond, the poet was born in 1894 in historic Cambridge, Massachusetts, today a suburb of Boston. His father, Edward E. Cummings, a sociology instructor at Harvard, became the minister of Boston’s South Congregational Church (Unitarian) (not to be confused with Old South Church) when his son was 5, succeeding South Congregational’s famous pastor Edward Everett Hale, a member of New England’s Hale and Everett families who had occupied the office for 43 years. Hale was a Unitarian clergyman, author (“The Man Without a Country,” 1863), and Chaplain of the U.S. Senate.

Childhood home of E. E. Cummings at 104 Irving Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, not far from Harvard Yard. Philosopher William James, who lived on the same street, introduced Cummings’ parents to one another.

The senior Cummings remained pastor at South Congregational until 1925, and his wife, son, and daughter Elizabeth attended services every Sunday. The following year a locomotive cut E. E. Cummings’ parents’ car in half during a New Hampshire snowstorm, instantly killing the father. His 62-year-old mother, though severely injured, survived. In 1940 Cummings penned one of his most famous, if not understandable — despite its quasi-traditional form — poems, an elegy: “my father moved through dooms of love.”

For most of his adult life, from 1923 until the year of his death, 1962, Cummings lived in an apartment in Manhattan’s avant-garde Greenwich Village, 4 Patchin Place, situated in an antiquated, blocked-off alleyway dating back to Old New York. It still exists, and his residence is commemorated with a plaque. (See photographic blogs at Forgotten New York, “Patchin Place, Greenwich Village” and “A Hidden Time Capsule Alley in Greenwich Village.”)

Cummings died, however, at his rural New Hampshire residence, the lifelong summer house he inherited from his parents, while chopping firewood with an ax. He’s buried in his mother’s Clarke family cemetery plot in the former village of Jamaica Plain (part of Boston), founded in the 1630s by Puritans seeking open farmland outside the city.

Poetic Style

Cummings’ highly distinctive modernist style is difficult to describe.

Some of his poems have correct grammar, spelling, punctuation, stanzas, and a customary look and feel to them. A striking example is “All in green went my love riding” (1923), a hypnotic ballad with allusions to classical courtly love, elusive in meaning but captivating and pleasingly rhythmic. Its deep structure is quasi-traditional. For some reason, it’s hard to shake from one’s mind.

Such poems are relatively rare, however. Sometimes numbered sequentially within individual collections, most poems are untitled and consist of disjointed lines. “Titles” have been artificially created from opening words or first lines.

The poet’s verse was typically experimental and radical, unconventional in technique, typography, syntax (word order and arrangement), running words together, and its use of eccentric punctuation, line breaks, hyphenation, syllables, capitals, lowercase, parentheses, ampersands, indentation, line length, and white space.

The style drove “some readers to frenzy and others to disgust,” it was said at the time.

Visual poetry, which prioritizes the look of a poem on the printed page, is incorporated into much of Cummings work.

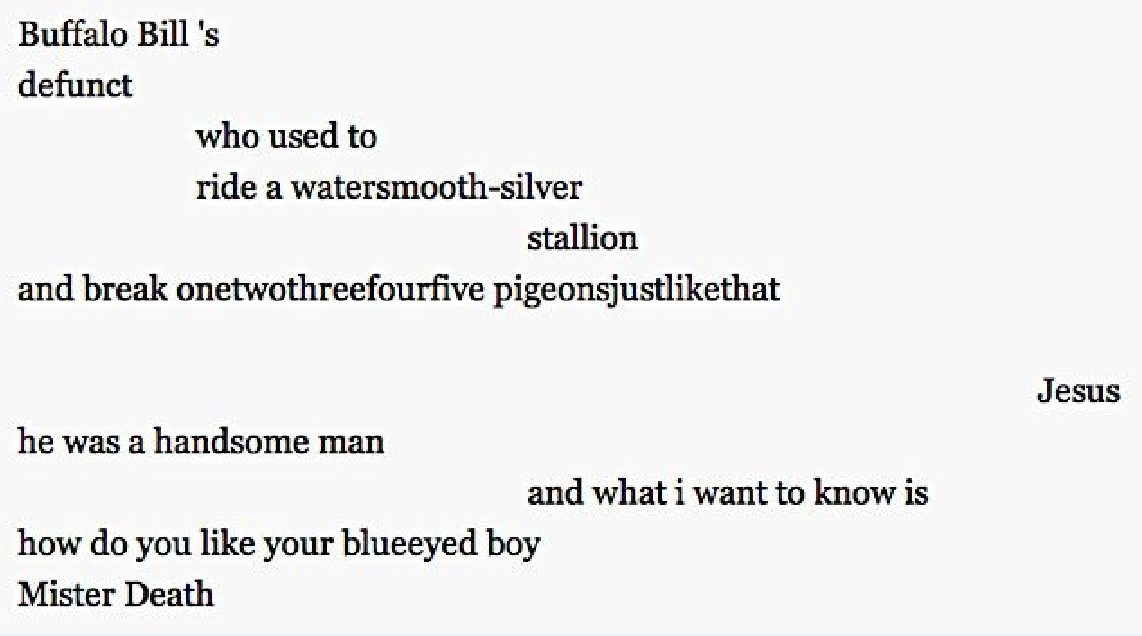

“Buffalo Bill’s,” discussed at the end of the essay, is a textbook example of Cummings’ visual poetry. It is reminiscent of Swedish American Carl Sandburg’s powerful but (visually) more elegant free verse poem “Grass” (1918), where so much of the effect depends upon the specific placement of each line on the page.

Cummings’ poetry is far more opaque than Sandburg’s — and more tethered to traditional forms. After calling attention to the fragmented visual shapes of Cummings’ poems on the printed page, The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (1993) says that “the deep structures of these poems [often] turn out to be traditional — a great many of them are exploded sonnets.”

Cummings’ biographer noted that his 1940 collection 50 Poems “contained less free verse, fewer experiments, and more formal poetry with distinct rhymes, meters, and stanzaic patterns; only three poems out of the fifty are written completely in free verse. Despite the use of conventional forms, the poems remain unconventional in their use of language, word order, and syntax.” As mentioned, the 1923 poem “All in green went my love riding” compactly exemplifies this aspect of his work.

Cummings also frequently employed half-rhymes, as well as full rhymes modified by deliberate visual misspellings.

Modernism Contra Understandability

It is often stated, inaccurately, that Cummings’ poetry was (or is) “accessible” to the ordinary reader. Examples of such statements include: “In his attempts to reshape poetry Cummings was also concerned with being widely accessible” and “Because of his style, Cummings’s poetry appears complex to the eye, but the ideas expressed through the words and punctuation are often simple.”

A much more accurate description of his body of work as a whole is a 1942 statement that “His poetry is “highly personal, a private message . . . from himself to the few who can receive it.”

However, the best critical assessment of this facet of his art — its comprehensibility or lack thereof — is that of Left-wing bisexual feminist Yankee poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, expressed in a letter in which she ambivalently recommended Cummings for a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1934. It is so explanatory and perceptive that it is worth quoting at length. Observe that the general thrust of what she says applies to modernist works generally.

It was “really funny,” she wrote, that she should help Cummings get a grant. “For if ever I disliked a man without ever having laid eyes on him, it is this same E. E. Cummings.”

[H]ere is a big talent, in the hands of an arrogant, peevish, self-satisfied and self-indulgent writer. That is to say, here is a big talent in pretty bad hands. . . .

I am not one of those who stand for the untouchable holiness of the capital letter and traditional typography. So far as I am concerned, Mr. Cummings may do anything he likes with the alphabet, the English grammar, and the multiplication table, provided only the result of his activities be something interesting, and, after a reasonable period of application, comprehensible, to a reader of culture and brains. Mr. Cummings may not, however, I say, write poetry in English which is more difficult for me to translate than poetry written in Latin. He may, of course, write it. But if he publishes it, if he prints and offers for sale poetry which he is quite content should be, after hours of sweating concentration, inexplicable from any point of view to a person as intelligent as myself, then he does so with a motive which is frivolous from the point of view of art, and should not be helped or encouraged by any serious person or group of persons. . . .

But, unfortunately for one’s splendid hate, which had assumed almost epic proportions, by no means all of Mr. Cummings [sic] poetry is of this nature. . . . [T]here is fine writing and powerful writing (as well as some of the most pompous nonsense I ever let slip to the floor with a wide yawn) . . .

(Millay to a Guggenheim Foundation representative, March 1934, quoted in Nancy Milford, Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay [New York: Random House, 2001].)

In sum: Cummings wrote many splendid — and popular — poems, but his work as a whole is by no means as accessible as is frequently stated or implied. You need only peruse the Complete Poems (1994) to instantly recognize this.

Cummings’ romantic poetry may be his most popular. It is sometimes said that “i carry your heart with me(i carry it in” (1952) is his single most popular poem.

But given today’s post-marriage, -monogamy, and -family world ravaged by feminism, homosexuality, No Sex, child and teen exploitation and violence (Rotherham, Jeffrey Epstein), ubiquitous pornography, state-sponsored medical mutilation of children and adults (“transgenderism”), fractured, nonexistent families and collapsing birth rates, much of this poetry does not stand the test of time, especially since modernism and modernists were instrumental in demolishing the foundations of sex, marriage, and family.

Cummings’ own sex and marital life, though by no means as bad as many of his avant-garde contemporaries, also testifies to this. Consequently, in this jaded age his plentiful, dewy-eyed romantic poetry often sounds false and insincere. It is difficult to read without cynicism.

Random (except that I’ve selected for comprehensibility) examples of such verse include “Amores (I)” (“your little voice / Over the wires came leaping”), “i like my body when it is with your” (1925), and “somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond” (1931).

Less characteristic, and less likable, “it may not always be so;and i say” (1917) romanticizes breakup with an element of cuckoldry.

Finally, there’s the crude “the boys i mean are not refined,” #44 in No Thanks (1935), self-published with money from his mother after fourteen publishers turned the book down. It’s straightforward. The reader has no trouble understanding it. But who is he talking about in 1935 New York City? My best guess is blacks, though race is not so much as hinted at, and I haven’t seen a single commentator ever suggest it. Everyone simply assumes he’s talking about whites.

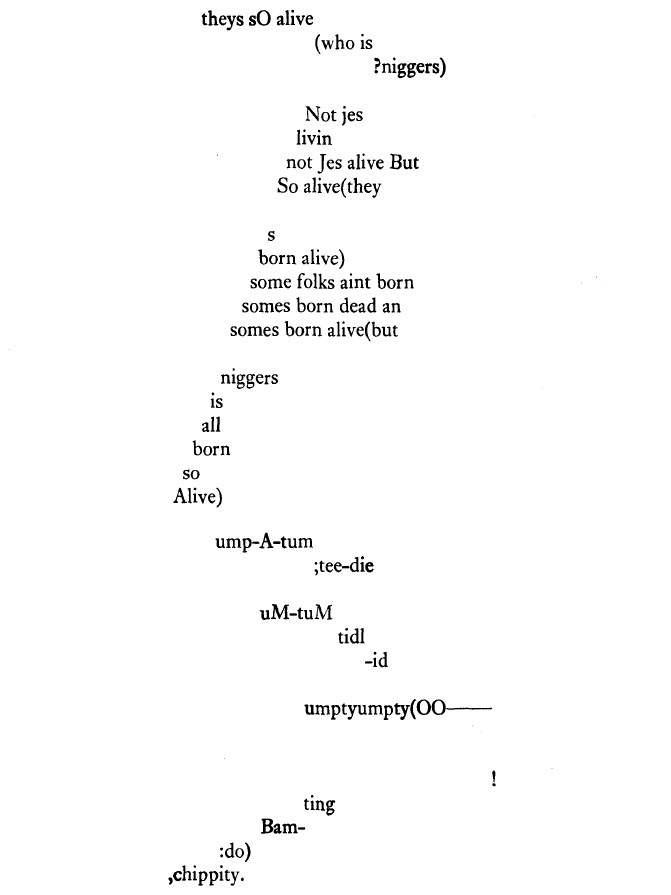

The immediately preceding poem #43 is “theys sO alive,” which is written in black dialect.

My favorite Cummings poem is “Buffalo Bill’s,” discussed at the end of this essay.

“i sing of Olaf glad and big” (1931), describing the fictional persecution and death of a stubborn nonconformist by a vicious gang of military sheep during WWI, epitomizes Cummings’ contempt for unjust authority.

The poet’s vivid, taken-for-granted description of the American officer corps as “a yearning nation’s blueeyed pride” shows how radically our native population has been decimated in what historically amounts to an øyeblikk.

The reader naturally identifies with the rebellious, strong-willed hero:

i sing of Olaf glad and big

whose warmest heart recoiled at war:

a conscientious object-or . . .

Resolutely refusing to knuckle under despite hideous beatings and tortures inflicted by officers and noncoms, America’s president finally threw Olaf

the yellowsonofabitch

into a dungeon,where he died

Christ(of His mercy infinite)

i pray to see;and Olaf,too

preponderatingly because

unless statistics lie he was

more brave than me:more blond than you.

The poem is invariably described as “based on a true story.” Though it doubtless contains a kernel of truth, the cartoonish, over-the-top savagery is imaginary. Exactly what the point was of basing such a good poem on an extravagant lie is unclear — though it does compel one to think of Jewish America’s treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (broomstick) and (by proxy) of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 (stick or blade).

His much applauded “the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls” (1923) is a patronizing poem unworthy of Cummings. He picked an easy target and kicked his subjects while they were down, knowing he’d win brownie points for doing so. Worse, he selected the wrong target. The offensive poem strongly reminds me of Iowa painter Grant Wood’s sneering Daughters of Revolution (1932). Wood at least had the decency to admit that Daughters was “A pretty rotten painting.” Neither man really understood the dire situation their people were in.

Anti-Communism

Many Cummings poems take shots at Communism.

(of Ever-Ever Land i speak (1936) ridicules the (supposed) idealism of self-styled “intellectuals.” The alternating stanzas in parentheses mock their Communist never-never land, as in the comical

(and Ever-Ever Land is a place

that’s measured and safe and known

where it’s lucky to be unlucky

and the hitler lies down with the cohn)

The satirical “BALLAD OF AN INTELLECTUAL,” one of the “Uncollected Poems” republished in Complete Poems, 1994, p. 899-900, covers similar ground, with its insolent references to Holy subjects: “Karl the Marks,” “Now all you morons of sundry classes / (who read the Times and who buy the Masses),” “or as comrade Shakespeare remarked of old / All that Glisters Is Mike Gold” (real name Itzok Isaac Granich, a vicious, well-known Jewish Communist Party USA member and writer).

and I mightn’t think(and you mightn’t,too)

that a Five Year Plan’s worth a Gay Pay Oo [GPU/OGPU, Soviet Secret Police]

and both of us might irretrievably pause

ere believing that Stalin is Santa Clause:

which happily proves that neither of us

is really an intellectual cus.

Pause/Clause is a conventional rhyme, except Claus is deliberately misspelled for visual effect to optically match “pause.” This was a recurring device he used in writing.

EIMI (New York: Covici, Friede, 1933) (the title is said to signify the Greek “I Am”) is a 432-page novelistic travelogue about Cummings’ visit to the USSR in Spring 1931.

Ezra Pound reviewed EIMI in the New English Weekly (December 20, 1934). Later, in his 1941 essay “Augment of the Novel,” he described the book as a key work of modernist prose, “one of the three books that any serious reader in 1960 will most certainly have to read if he wants to get any sort of idea of what happened in Europe between one of our large wars and another.” The other two books were James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) and Wyndham Lewis’s The Apes of God (1930).

EIMI’s characteristically abstract prose renders it virtually unreadable. Even Pound, as game as anybody for this kind of thing, admitted that many found the book “painful to read,” and advised Cummings that the longer a work is, the more comprehensible passages it must contain, at least at intervals.

The passage of time and the heavy veil of secrecy and lies with which elites have protectively concealed the repugnant history of their gangster regime makes the book even more inscrutable today.

The primary value of EIMI isn’t the text, or any explicit message it conveys, but the fact that Cummings viewed Communism as repulsive at a time when it was universally worshiped; he “loathed” the USSR (his word).

Despite EIMI’s heavy cloak of unintelligibility, Jews and Leftists, like pigs hunting for truffles, sniffed out the author’s deviationism anyway, despite not understanding the book any better than anyone else. Some things never change.

Nevertheless, Cummings had many Left-wing acquaintances.

In Paris, the odious Jew Ilya Ehrenberg, later infamous for instigating mass hate, rape, and murder of thousands of Germans by Red Army troops during WWII — unprosecuted war crimes — personally arranged Cummings’ trip to the USSR. He put the poet in touch with fellow Jew Vladimir Lidin (real name Gomberg), the son of a well-to-do Moscow exporter who served as Cummings’ initial guide in Moscow. Lidin was a famous Soviet writer of the 1920s. In WWII he created Red propaganda against Germans, including yarns about atrocities against Jews.

During the trip, Cummings translated French Communist Louis Aragon’s propaganda poem “Le Front Rouge” (“The Red Front”) into English, doubtless for pay. The poem was a celebration of Communism and Stalin’s Five-Year Plan. Cummings called it a “hymn of hate.” The translation was published by Contmpo Publishers of Chapel Hill, North Carolina in 1933, and is included in the Complete Poems (1994) (pp. 881-897), with Aragon’s French original on every other page, faced by Cummings’ English translation of the same lines on the opposite page.

At a Moscow luxury hotel specially designed and equipped for (heavily-monitored) foreign pilgrims, Cummings ran into Harvard alum Harry Dana, an American academic, Communist, and homosexual who resided off and on in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1935. Dana wrote English language books about Soviet theater and drama for Western audiences.

A scion of two New England families, his full name was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana. His paternal grandfather was Richard Henry Dana, Jr. (Two Years Before the Mast, 1840), his maternal grandfather Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. A short, highly laudatory capsule biography of Dana is hosted by the National Park Service on its official website. By omission, it lies to readers about Dana’s Communism, though it does mention with pride his affection for socially elite young men.

Next, Cummings hooked up with Jack London’s daughter Joan London, a member of the Communist Party USA, and her Jewish husband Charles Malamuth, born in Russian Poland, but in the 1920s an academic at the University of California, Berkeley. Cummings lodged with the couple while he was in Moscow.

Malamuth later trod a familiar path from Stalinism to Trotskyism to 1950s-era US-financed “anti-Communist” neoconservatism/neoliberalism run by Jews. In 1970 Joan London co-authored a book glorifying Mestizo intruders in America, So Shall Ye Reap: The Story of Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement.

Despite all this Cummings deserves credit for rejecting Communism in 1931, if not earlier — long before most wealthy and fashionable people did.

The Friendship of E. E. Cummings and Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound was a chief architect of English and American literary modernism. His “influence on the development of poetry in the twentieth century has unquestionably been greater than that of any other poet.” “In The Cantos [1915-1970] he wrote the most difficult poem of the period with the most numerous and far-ranging allusions — a poem that is probably the most unread.” (Dictionary of Literary Biography).

Pound was “Of Old American stock,” with “roots in the American past.” (Thomas Fleming, Chronicles magazine, February 1991, p. 25.) The Dictionary of Literary Biography (1986) says that “Many people have thought him ‘un-American’ — an adoptive European. But Pound always considered himself completely American.”

His direct paternal line (surname Pound, excluding the wives) traces back to England through colonial New Jersey in the 1600s. His Pennsylvania-born grandfather was a prominent Wisconsin businessman and Republican state legislator, Lieutenant Governor, and U.S. Congressman (1877-1883). Through his mother Pound was a member of the Yankee Wadsworth family, which included poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and colonial legend Joseph Wadsworth, who by tradition concealed Connecticut’s Charter in Hartford, Connecticut’s Charter Oak in 1687 to prevent its confiscation by the English governor.

Cummings and Pound first met in Paris in 1921. The two hit it off immediately and developed a lifelong friendship.

The first surviving letter between the two dates from 1926. Between then and February 1933 they exchanged eight letters, mostly solicitations from Pound requesting literary contributions from Cummings for various projects.

In 1933, however, Pound read EIMI and, sensing a kindred spirit, their correspondence kicked into high gear. Between that date and 1939, the two men exchanged 82 letters. In several of them, Pound referred to and commented upon the book.

Max Eastman, while still a Communist and Trotskyite, dined with the two men in 1939. In his estimation, Pound was “one-eighth as clever and all-sidedly alive as Cummings. He seemed to subdue Cummings, though, being burly and assertive beside that slim ascetic saint of poetry.”

Cummings’ view of Pound can be glimpsed in the opening salutation of a letter he wrote to him in 1941, and a statement he sent to Pound’s biographer in 1957.

In the letter, Cummings greeted Pound as “our favourite Ikey-Kikey, Wandering Jew,Quo Vadis,Oppressed Minority of one,Misunderstood Master,Mister Lonelyheart,and Man Without a Country.”

To the biographer, Cummings wrote: “EP [Ezra Pound] is the authentic ‘innovator’;the true trailblazer of an epoch;this selfstyled world’s greatest and most generous literary figure.”

Pound, who’d settled in Italy in 1924, became a fan of Mussolini’s Fascism, which he promoted in English language radio broadcasts made from Italy to England and the United States during World War II. In his broadcasts, he attacked FDR, the New Deal, Jews, and modern banking.

When the Allies invaded Italy in 1945, Pound voluntarily surrendered to American authorities.

Jews hated Pound, who they viewed as a true anti-Semite, that is, an opponent who had developed, and operated from, a “consciously-evaluated” position, unlike, say, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and others whose anti-Jewish attitudes were shallow conventional cultural inheritances.

As a result, Pound was punished much the way white political prisoners were in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. For weeks he was held prisoner in an open-air cage in Italy. In 1946 he was shipped to Washington, D.C., declared insane by the federal government, and for 12 years locked away as a political prisoner (or, more accurately, a racial prisoner) in the government-run St. Elizabeths madhouse in Washington, D. C. Reading about Pound’s grim, bizarre ordeal forcefully reminds the reader how little difference there is between America and the Communist regime it allied itself with, and whose totalitarian empire it subsequently expanded throughout Europe and the world.

Cummings remained loyal to Pound, both privately and publicly, during and after the long period of Jewish-instigated hysteria and racial hatred that was orchestrated against the poet. He visited Pound at St. Elizabeths.

Anti-Interventionism

As “i sing of Olaf” (1931) demonstrates, Cummings was not a fan of WWI. After US entry into that war he volunteered to serve in the Ambulance Corps of the American Red Cross in France. He and a friend wrote letters home expressing anti-war sentiments.

French censors poring over people’s mail ordered the two Americans to be arrested and imprisoned. Cummings was sent to a military detention camp in Normandy, where he spent three months. This experience provided the basis for his autobiographical novel The Enormous Room (1922).

As WWII loomed, Cummings remained steadfastly anti-interventionist. He refused to support the Soviet Union before or after the collapse of the German-Soviet pact.

When Charles Lindbergh gave his famous September 11, 1941 anti-war speech on the radio in Des Moines, Iowa, saying that Britain, Jews, and the Roosevelt Administration were responsible for dragging America toward war, Cummings expressed his cynicism about the vicious backlash that ensued to Ezra Pound: “A man who once became worshipped of one thousand million [1 billion] pubbul . . . is excoriated for,for the nonce, freedom of speech.” (In 1940 the world population was 2.3 billion.)

Immediately after Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the Second World War, the formerly noninterventionist America First Committee endorsed the conflict, called for “Victory,” and disbanded itself. But Cummings remained unswayed. He did not embrace martial fervor like so many isolationists did.

Race and Jews

Cummings is among dozens if not hundreds of leading “anti-Semitic” Western writers Jews want banned or censored so Gentiles can’t read their work. (Anonymous, When Victims Rule: A Critique of Jewish Pre-eminence in America, n.d., p. 604, citing Brooklyn-born Jewish dual citizen Mark Gelber’s “What is Literary Antisemitism?” Jewish Social Studies [Winter 1985].)

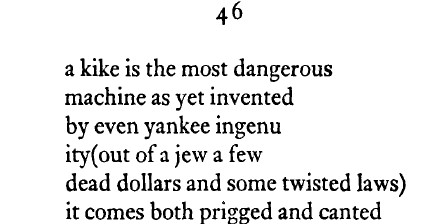

Marc Miller attributed Cummings’ anti-Jewish beliefs to frustration over his failure to become a screenwriter in “Jewish-dominated Hollywood.” The author said Jewish accusations of anti-Semitism focus primarily on a single poem (out of 2,900 total). (“Jews and Anti-Semitism in the Poetry of E. E. Cummings,” [Spring, October 1998].)

This claim flies in the face of another “expert,” who sweepingly says Cummings’ “antisemitic expressions began in the 1920s and lasted thirty years.”

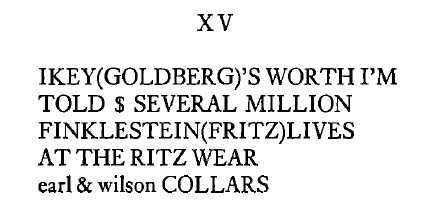

Here is the “controversial” poem in its entirety:

The last line of the poem as Cummings actually wrote it was, “it comes both pricked and cunted,” which, unlike the existing version, makes sense. (O, Barbara Lerner Spectre!) Cummings’ Jewish editor, Theodore Weiss, ordered the change.

The preceding poem in the same collection, #45, contained Politically Incorrect, if inscrutable, allusions to Indians and Communism:

Also deemed anti-Semitic is “IKEY(GOLDBERG)’S WORTH I’M” from is 5 (1926).

Poem #54 in No Thanks (1935), “Jehovah buried,Satan dead,” contains the lyrics:

Eternity’s a Five Year Plan:

if Joy with Pain shall hang in hock

who dares to call himself a man . . ?

and, referring to radio broadcasting:

to kiss the mike if Jew turn kike

who dares to call himself a man?

A short private statement Cummings wrote in 1939, not intended for publication, exhibits startling insight into the radically different ways Jews and Aryans experience race and individuality.

In pencil across the top of the typewritten page, he wrote, “how well I understand the hater of Jews!”

The Hebraic they–it permeates everything, like a gas or a smell. It has no pride–any more than a snake has legs. Above all:it is low–this heavy,hateful shut something crushes-by-strangling whatever isn’t it . . . makes any quick bright beautiful beginning impossible–stops inspiration just as the spirit’s lungs are opening:for it cannot endure free,loving,gay; its own imprisoning pain perpetually must revenge itself on every soaring winged singful bird! . . . The difference between Jews and other people seems to be that what’s non-racial or differentiating exists(in Jews)only apparently,only superficially; whereas anyone else’s identity goes down through innumerable layers right into his or her soul(and always more intense,not less). Anyone else is,so to speak,vertically an individual. The Jew is merely a horizontal layer or surface of individuality–under this,all depths are UN. Also,whereas the Xian’s [Christian’s] verticality may extend itself upward . . . with as much height beyond it as there’s depth beneath, the Jew’s self . . . can never be heights.

(Quoted in Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno, E.E. Cummings: A Biography [2004], p. 427.)

Cummings has also taken flack for references to blacks that are considered less than worshipful.

“but if i should say” (from is 5, 1926) contains the lines “trouble adds / up all sorts of quickly / things on the slate of that / nigger’s / face.” It also contains the image “mr rosenbloom picks strawberries / with beringed hands.”

“one day a nigger” heretically implies that at least one nigger somewhere wanted to be white. From Xaipe: Seventy-One Poems (1950), complete:

one day a nigger

caught in his hand

a little star no bigger

than not to understand

“i’ll never let you go

until you’ve made me white”

so she did and now

stars shine at night.

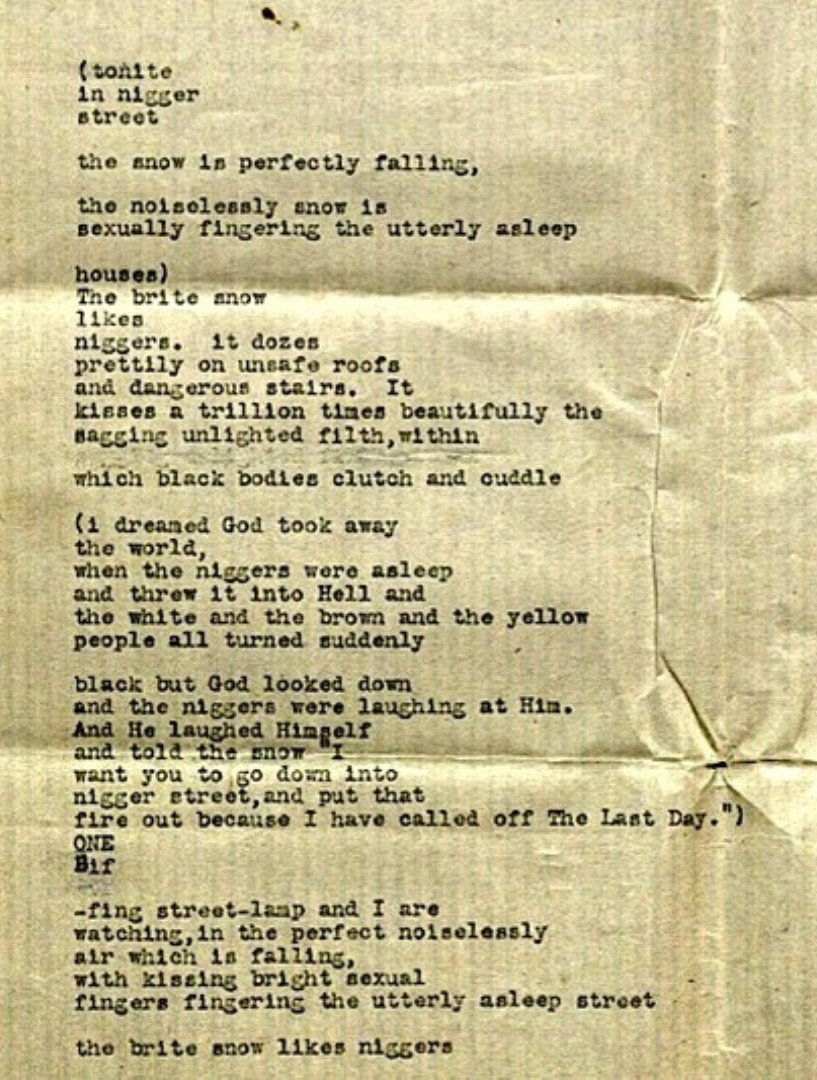

“(tonite” (c. 1916) was never published, not even in the 1991 Complete Poems, which contains many pages of previously unpublished poetry. It was discovered in 2010 by an author searching a folder of correspondence between the poet and Scofield Thayer at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The poem’s repetitive use of “the N-word,” as the insufferable snobs called it in 2010, set ruling class hearts a-flutter with self-righteous indignation. The Atlantic Monthly melodramatically proclaimed, tabloid-style (in 2011, a half-century after the poet’s death!), “Noted McCarthyite e.e. cummings Also Apparently Racist.”

Plays

Cummings wrote four plays, all in modernist style.

Of his first, the three-act HIM (1928), he said, “relax, stop wondering what it is all ‘about’ . . . this play isn’t ‘about,’ it simply is. . . . Don’t try to enjoy it, let it try to enjoy you. Don’t try to understand it, let it try to understand you” — clichéd posturing that makes your eyes glaze over and your mind go blank, a problem that plagues much of Cummings’ poetry and prose as well.

Most relevant for our purposes is TOM (New York: Arrow Editions, 1935), a libretto for a modernist ballet based on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852).

Jewish department store heir Lincoln Kirstein (Filene’s), a wealthy patron of modern art and the son of a leader of American Jewry, asked Cummings to write a libretto for a modernist ballet. Kirstein and the half-Georgian, half-Russian choreographer George Balanchine had co-founded the School of American Ballet; later they co-founded the New York City Ballet.

Kirstein said that when he read Cummings’ work to Balanchine the choreographer “said it might well be splendid prose or even poetry, but there were no pretexts therein for dancing.” It has never been performed.

The ballet’s music was written by homosexual Jewish composer David Diamond, who Cummings (and many others) disliked.

In a July 1939 journal entry, Cummings noted that a “visit by a fag” (Diamond) to his New Hampshire farm interrupted his work. Absent Diamond’s musical gift, the composer would be “a misfit jewboy suckled on cinema. He’s willing & generous; he’s also unlovely and neurotic. . . . His fairyact over a bat(UGH!!!aren’t they HOAR-ubble!) is the saddest piece of theatre I’ve ever had to behold.”

But he permitted the composer to live rent-free at Patchin Place for the summer, secured financial assistance for him (Cummings’ common-law wife “found 2 poorlittlerich goygirls” to give the Jew money), and defended him to Ezra Pound, who disliked him. Cummings argued to Pound that Diamond’s poverty had been “immeasurably complicated by a steadfast refusal to kiss the reigning arse of(projew)Roosevelt II.”

Originally “unbigoted” toward homosexuals, Cummings’ views later changed. Unpublished during his lifetime, “in hammamet did camping queers et al” (from Etcetera: The Unpublished Poems, 1983), recorded his observation of homosexuals (apparently not white) in Tunisia. According to his biographer, the poem is “not expressly anti-homosexual,” but is “hardly flattering either.” (The biographer thought it should be flattering.) The poet expressed “a mix of pity, intrigue and revulsion.” The writer was even less enthusiastic about a one-line private note from the late 1930s: “Kweers Kikes Kumrads–the new KKK.”

You would think nothing interesting could be written about this ballet, but, surprisingly, there is such an article: Gavin Raker, “Choreographing History: Uncle Tom as Modernist Ballet.” (SPRING, the Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society, October 2003.)

All four of Cummings’ dramas were collected as Three Plays and A Ballet, George J. Firmage. ed. (New York: October House, 1967).

Cummings’ Refusal to Accept the Responsibilities of Fatherhood and Family

The play Santa Claus: A Morality (1946) was inspired by his disclosure that same year to his adult daughter and only child Nancy (née Thayer) Roosevelt (later known as Nancy T. Andrews after her second husband), while painting her portrait in Greenwich Village, that he was her biological father, a fact previously unknown to her.

Nancy was Cummings’ illegitimate child by his first wife, a rich young beauty from Troy, New York named Elaine Orr, who had become pregnant with Cummings’ child while still married to his wealthy financial patron and friend, Scofield Thayer, heir to a New England textile fortune.

For complicated reasons, all three knew who the real father was. Thayer was a modernist, a believer in “free love” who refused to have sex with Orr after their marriage, subsequently took a shine to adolescent boys, and finally became mentally ill. He did not mind that his young wife was having sex with his friend because theirs was a marriage in name only — though Elaine had not known this would be so before they married.

Thayer and Cummings callously urged Elaine to have an abortion (this was in 1919), which she refused to do.

Cummings “‘wanted E[laine] as a mistress.’ He then added, ‘I was not interested in her having a child — in fact, I advised her, like Thayer (following his suggestion) to PREVENT the child, with an operation.’”

All quotations about this tangled affair are from “Friends and Lovers,” published in the Guardian (UK) in 2005. It is an extract from Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno’s E.E. Cummings: A Biography (2004). Read the Guardian account for more information, along with “A Memorial: Nancy T. Andrews, Daughter of E. E. Cummings” (SPRING, 2005-2006), written after Nancy’s death in 2006. Remember: both accounts are biased in Cummings’ favor.

Thayer agreed to pose as Nancy’s father, and assumed financial responsibility for raising the child. When the baby was born in December 1919, the birth certificate listed Thayer as father (which all three parties knew was false), Elaine as the mother, and the girl as Nancy Thayer.

Cummings then lost interest in Elaine, writing that he “bitterly resented” Nancy. “Now Nancy becomes my rival, I supress my real hatred I cannot love E as a prostitute but as a mother E. has less sexual appeal but because she is the mother of my child I refuse to admit it.”

She [Elaine] does everything for Mopsy–my child. . . .

i sit back,do nothing to help–never ask her

to marry me

i don’t really, want to participate in my own child!

i have no thought of Mopsy — except as Elaine’s.

In 1921 Thayer and Elaine divorced. Thayer established a $100,000 trust fund for Nancy’s “support, maintenance and education.” However, he was as emotionally uninvolved with the child as Cummings was.

Cummings and Elaine hooked up again sexually, and in 1924 Reverend Edward Cummings married the couple in the Cummings family home in Cambridge. E. E. Cummings formally adopted his own 4-year-old child, who was not informed of the adoption, or of the fact that he was her real father. At Cummings’ insistence, the child retained the name Nancy Thayer. Cummings instructed the child to call him Estlin, and made sure she never knew he was her father, or thought of him that way.

Cummings and Elaine separated two months after their marriage, and divorced shortly thereafter.

Cummings married another woman, but divorced her after only three years. In 1934, fashion model Marion Morehouse became his common-law wife, and the two lived together until his death in 1962.

Nancy did not learn the truth about her background until her father broke it to her at the portrait session in 1946, at which point he had not seen her for 20 years. She tried to establish a relationship with her father — she had two Roosevelt children at this point (Cummings’ grandchildren) — but was rebuffed.

These facts expose Cummings’ egocentrism, selfishness, and immature refusal to accept the responsibilities of parenthood and family, common behavior among his elite bohemian friends. He had even wanted to abort his own daughter. The entire affair is an example of everything wrong with modern family formation.

It is necessary to add that Cummings had a foreign-born Jewish psychoanalyst, Freud disciple Fritz Wittels, to whom he confided his most intimate doubts and secrets. Worse, Cummings followed Wittels’ relationship and sexual advice. How much of his reprehensible behavior was attributable to his own selfishness and irresponsibility, and how much to alien influence is impossible to say. It was a mixture of both.

Freud’s name crops up periodically in Cummings’ writings, leaving the impressions that the poet took psychoanalytical theory seriously — as did most leading whites at the time. TOO contributor Edmund Connelly has frequently observed that psychoanalysis was a powerful weapon wielded against us by our destructive enemy. It’s hard to believe whites were so stupid.

When Cummings painted Nancy’s portrait in 1946, she was married to President Theodore Roosevelt’s grandson (Joseph) Willard Roosevelt, a pianist and composer who died in 2008.

Willard Roosevelt was the son of Kermit Roosevelt, who committed suicide in 1943 at age 53, and brother of OSS and later CIA operative Kermit Roosevelt, Jr., who died in 2000.

Paintings

Cummings created hundreds of paintings, drawings, line art, and caricatures that he regularly exhibited at New York galleries. He painted in the afternoons and wrote at night.

In my well-thumbed first edition of Webster’s Biographical Dictionary (1941), a delightful volume, Cummings’ brief three-line entry described him first as a painter. The word “poet” didn’t even appear: “American painter and author. Studio in New York City.” Jonathan Yardley explains this: “Not until the 1950s did Cummings become a Famous Poet, with the publication of his Poems 1923-1954 [1954] and his emergence as a star on the college lecture circuit. His revolutionary style put off many readers for years.”

Again, his poetry is not as accessible as many people think.

CIOPW (1931) is a collection of Cummings’ drawings and paintings. The five capital letters in the title derive from the initial letters of the materials used to create the works within: Charcoal, Ink, Oil, Pencil, and Watercolor.

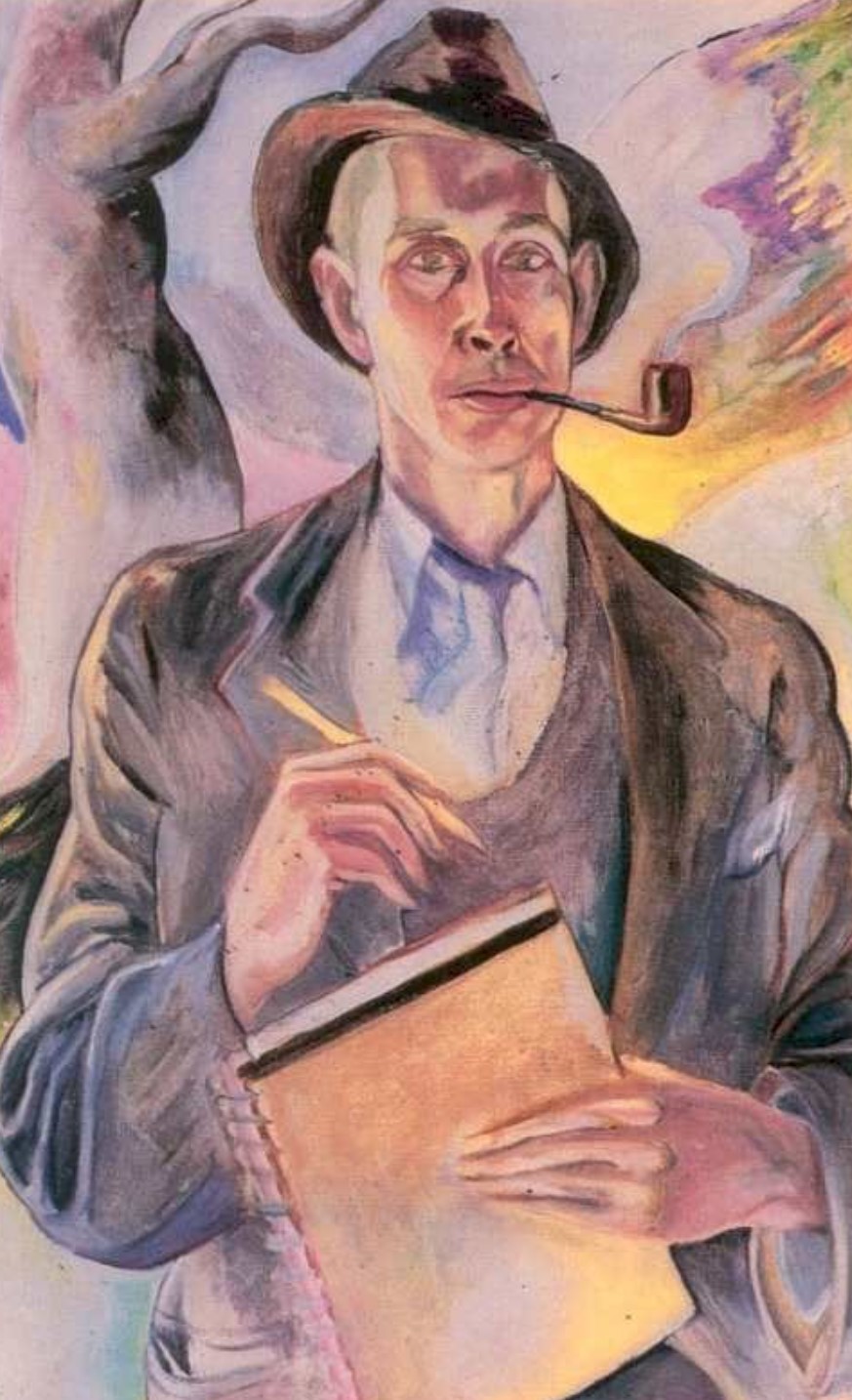

An avant-garde abstractionist after WWI, Cummings showed his early paintings at modernist exhibitions. But his later work grew more realistic and figurative.

Some of his artwork can be seen here. One of his best self-portraits has a distinctly Thomas Hart Benton-ish look to it, albeit with a different use of color.

Vanity Fair Essays

From 1922 to 1927, at the request of legendary editor Frank Crowninshield (see Crowinshield family), Cummings was a regular contributor to the immensely popular Vanity Fair, the literary adjunct of Café Society.

(“Crowinshield’s [Salem, Massachusetts-born] great-grandfather, Benjamin Crowinshield, was Secretary of the Navy under both Presidents Madison and Monroe — at a time when he personally owned more ships than the American Navy.” Frank Crowinshield and Cholly Knickerbocker became “the last of the arbiters of a crumbling” white social elite. Cleveland Amory, Who Killed Society? [1960].)

“The Adult, the Artist and the Circus” (October 1925) anticipates, in subject matter and style, the essays of Tom Wolfe. (I was surprised to discover that another writer also noticed this — as early as 1971: “Cummings wrote about popular culture in the 1920’s-1930’s much the same as Tom Wolfe was writing about it in the 1960’s.”) To be sure, as an essayist Wolfe is far superior — more accomplished, brilliant, and artistically and pyrotechnically dazzling. Nevertheless, the similarity exists.

Describing the excitement and danger of the three-ring circus under the big top, Cummings observes, “This may be described as a gigantic spectacle, which is surrounded by an audience, as were the tragedies of Aeschylus and the comedies of Aristophanes — in contrast to our modern theatres, where an audience and a spectacle merely confront each other.”

“The Tabloid Newspaper” (December 1926) ends with the following observation:

We discover, to our astonishment, that what has really happened to America from the day of Plymouth Rock and the Bible to the day of Big Business and the tabloid newspaper is exactly the opposite of what the economists and their ilk would lead us to suppose. America has grown down, not up. From Pilgrim Fathers we have become Pilgrim Children. The United States, today, is nothing more nor less than a Great Big Egoistic Baby. When, glancing about us, we perceive the whole world following this infantile nation of ours, let us remember the Bible of the Pilgrim Fathers, wherein it is written that “a little child shall lead them”. And let us admit that the Pilgrim Fathers, all things considered, may not have been so limited as we originally supposed.

At least the Pilgrim Fathers used to shoot Indians: the Pilgrim Children merely punch time-clocks.

All save two of Cummings’ Vanity Fair articles were reprinted in E. E. Cummings: A Miscellany (1958, 1965, 2018). The Vanity Fair essays are easily the most accessible of his writings. Others in A Miscellany, like “T. S. Eliot” (The Dial, June 1920), are modernist.

Not all the Vanity Fair pieces impress. “When Calvin Coolidge Laughed” (April 1925) boasts a great title, but fails. The author personally excluded two other essays from A Miscellany for the same reason.

“Buffalo Bill’s”

“Buffalo Bill’s” (1923) is one of E. E. Cummings’ best-known — and best — poems. William F. Cody died in 1917; the next day, Cummings jotted the first lines of a draft of his famous poem. “Buffalo Bill’s” was published in the journal Poetry in 1920.

It is amazing the different interpretations people bring to this relatively straightforward work. Typically, a sarcastic, condescending tone toward the English/French Huguenot-descended hero is alleged. Many people, of course, simply echo what others have said.

That interpretation is incorrect — the poet is reverent toward its young hero . . . and contemptuous of Death, despite acknowledging its all-consuming power.

Lightning-lit like midday from blackness for a fraction of a second, then plunged to blackness again before the mind has time to process the scene, you perceive tremendous vitality, the youthful figure in action, the exceptional man — and inescapable Death.

Of interest:

E. E. Cummings, Complete Poems, 1904-1962, edited, revised, corrected, and expanded by George J. Firmage (New York: Liveright, 1994), 1,135 pp.

To the contents of the individual volumes published during Cummings’ lifetime were added 36 “Uncollected Poems” from scattered published sources issued between 1910 and 1962, and the 164 poems previously published for the first time two decades after Cummings’ death under the title Etcetera: The Unpublished Poems of E. E. Cummings (New York: Liveright, 1983).

Pound/Cummings: The Correspondence of Ezra Pound and E. E. Cummings, edited by Barry Ahearn (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996).

Cummings wrote nearly everything (poems, prose, even letters) in a habitually mind-numbing modernist style. You can sense what a chore it is to plow through large amounts of this material by reading a short 1941 letter Cummings wrote to Ezra Pound — though it does contain characteristic flashes of humor and disdain. FDR Democrat and fellow traveler (“fellow traveler” is a translation of Russian popuchiki, a nonmember who supports the Communist Party line) Archibald MacLeish becomes “macarchibald maclapdog macleash,” and Cummings’ contempt for the Left is undisguised: “whatsoever bully(e.g. all honourless&lazy punks twerps thugs slobs politicos parlourpimps murderers and other reformers) . . .”

A partial description of the letters:

Ezra Pound and E. E. Cummings carried on a long and varied correspondence from the 1920s until Cummings’s death in 1962. This volume collects all of the important letters from this important friendship in the history of modern poetry.

Throughout the correspondence both poets reveal themselves and their beliefs to a remarkable degree. Pound entrusted to Cummings details of his political outlook in the 1930s and 1940s, including his opinions about Mussolini’s Italy. . . .

Similarly, these letters should provoke a reevaluation of Cummings. Critics have treated Cummings’s political views as either strictly private matters or merely incidental to his art. The letters, however, show that Cummings’s radically conservative political opinions are wholly consistent with his poetics.

* * *

Don’t forget to sign up for the weekly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Whither Thou Goest, Diaspora?

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy Rozdział 2: Hegemonia

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 1: Nowa Prawica przeciw Starej Prawicy

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Thank You, O. J. Simpson

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

10 comments

Very interesting essay, thank you.

A most informative article on a thoughtful poet. I always liked E.E. Cummings. His poem ‘In Just’. (‘In Just-When the world is puddle wonderful…’). Was a big favorite in high school literature class.

I always liked his poem about President Harding:

‘the first president to be loved by his

bitterest enemies” is dead

the only man woman or child who wrote

a simple declarative sentence with seven gram-

magical

errors “is dead”

beautiful William Gamaliel Harding

“is” dead

he’s

“dead”

if he wouldn’t have eaten them Yapanese Craps

somebody might hardly never have been

unsorry, perhaps

What a mixed bag. Yankee genius and pretentious modernist, and more.

Thank you for this…Enjoyed it tremendously.

“Kweers Kikes Kumrads–the new KKK.”

Ha! I’m using that one.

I just wanted to say I really appreciated this essay, although I haven’t finished it yet—I’m a very slow reader—taking me several days. Something I notice, do you think Cummings or Celine was an influence on the other? Their subject matters are dissimilar, but that style of startling amalgam and juxtaposition in a telegraphic style are quite reminiscent of one another, wouldn’t you think? Also, the vulgarity injected by both is very similar. Cooler in Celine, as I don’t think it belongs in poetry so much.

I am mixed on Cummings. I tend not to like his later really experimental stuff, but I do love his earlier poetry, when it was closer to conventional verse, poems like In just- and When God Let’s My Body Be, although there are some later good poems like If Everything Happens that Can’t be Done.

Is he anti Semitic or anti anything? Probably not as he hits everyone at some point. Politically he seems like Jeffers, rational, against america going to the insane wars.

I was just gearing up to read Enormous Room when this essay came out—strange coincidence.

Last year I finished the book 100 Selected Poems of Cummings, and I liked it, as it had all the more tolerable and better poems of Cummings, or the compiler probably had similar aesthetics to me. I recommend that if you find the bizarre ones off putting.

I do not think that Cummings was an influence on Céline, never heard of it anyway. I think this would have appeared in the many studies devoted to Céline. As a matter of fact I do not see any resemblance in their style.

Sir, this is COUNTER-CURRENTS! We write ORIGINAL THESES here,and not regurgitate the scribblings of pedants! This is COUNTER-CURRENTS!

I’ve never come across any information about Céline in connection with Cummings, though they were both modernist writers, shared a certain proclivity, and Cummings could read (and translate) French. Of course, I’m sure you know Kurt Vonnegut said many times that he admired Céline’s writing, and had been influenced by it.

Your thought is not out in left field. In a long interview discussing Cummings, The Enormous Room, and various modernist writers, his biographer was asked about any connection between the two by an interviewer who obviously had the same thought you did. CSL is the biographer, RC the interviewer:

“RC: With [Céline’s] Journey and The Enormous Room, besides portraying horrific events, we also find a great deal of black humor and tragicomedy. And all of which is portrayed with an abundance of literary innovation. Do you feel that Cummings and Céline share these things in common?

“CSL: Oh, absolutely. . . .

“RC: What did Céline think of Cummings?

“CSL: We don’t know.

“RC: Is there any evidence that he was aware of Cummings?

“CSL: Céline was aware of Cummings. Whether Cummings was aware of Céline, I don’t know, because I’ve never found any reference anywhere, when I was looking through all that stuff, to Céline. And I would have seized on it, because I would have found that interesting. They shared a lot in common. . . .

“I know that Céline was aware of Cummings because he was very aware of North American literature. Cummings was widely translated into French. And Céline knew English, to some degree. And he would have sympathized, because Cummings himself was an anti-Semite. . . . When that big blowup happened with Cummings being sort of outed as an anti-Semite, you could be sure that Céline took notice.”

http://www.tygersofwrath.com/EECummingsandtheEnormousRoom.htm

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment