Everyone loves a good underdog story. It’s what Hollywood does well. Not to give Hollywood too much credit since I’ll posit that the underdog story is uniquely suited for cinema, regardless if it’s Hollywood or Bollywood or some independent genius shelling out the shekels behind the scenes. I suspect the reason can be boiled down to two words: “home cookin’.” With the right script and performance, filmmakers can get an audience to fall in love with a character despite his personality quirks and manifest flaws. And when this character defies the odds by taking on authority in pursuit of justice, well, the stories just write themselves, don’t they?

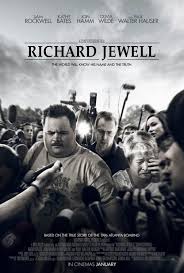

Legal dramas are a particularly reliable type of underdog story, and Clint Eastwood has recently added a particularly memorable one to the genre with Richard Jewell.

Based on true events, Richard Jewell tells the story of the security guard who discovered a bomb in Centennial Park during the Atlanta Olympics in 1996. Jewell, played beautifully by Paul Walter Hauser, notified the authorities who were in the process of clearing a perimeter around the bomb when it detonated, killing two people and injuring over a hundred. Without Jewell’s quick thinking, however, many more would have been killed. This turned Jewell into a hero and minor celebrity until the FBI decided to make him a suspect for planting the bomb and proceeded to ruin his life.

Jewell then reaches out to an abrasive and down-and-out attorney named Watson Bryant (played impeccably by a scruffy Sam Rockwell) and our underdog story is born. Davey, meet Goliath.

Several aspects of Richard Jewell make it stand out from other legal dramas—the most obvious being the titular character himself. He’s obese, he wears a goofy mustache, he lives with his mother, and—most importantly—he’s smart while appearing to be dumb. The audience quickly learns that, despite all appearances, Jewell is perceptive and competent. But he’s also principled and naïve and too unassuming to wear his education or intelligence on his sleeve. This makes him a prime candidate for being underestimated by his enemies.

There is an annoying stigma these days attached to grown men who live with their mothers. Yes, in many cases, such men are losers addicted to porn or drugs or video games. On the flipside however many of these men are gainfully employed bachelors who have genuine affection for their moms. Richard Jewell falls into this latter category and demonstrates quite clearly that there is nothing wrong with that. At their lowest point in the story, when the FBI had just raided their apartment and with an army of hostile media camped outside, Jewell blows up at his mother (played wonderfully by a matronly Kathy Bates) and causes her to leave the room in tears. Soon after, he apologizes, and their drawn out reconciliation is a thing to behold.

It is this stigma which initially draws the FBI to Jewell. Since he is a white, no-account weirdo with a spotty employment record and some questionable decisions from his youth, he fits the profile of the lone wolf with a hero complex—that is, a man who manufactures a crisis in order to manufacture his own heroism in solving the crisis. This is all they have on Jewell, and they cynically think it’s enough to manufacture a suspect. Jon Hamm does not simply portray the arrogant and corrupt Agent Shaw who leads this unwarranted investigation, he embodies it. I cannot remember a performance this subcutaneous in all the films I have ever seen. Hamm’s performance is so comprehensive in Richard Jewell that I am actually tempted to lose respect for him as a person. Only a true jerk and can play a jerk this well on screen. (Not entirely serious here, but you see what I mean.)

Where most legal dramas pit plucky, small-town underdogs against greedy, malignant corporations (Dark Waters being a contemporaneous example), Richard Jewell pits its plucky, small-town underdogs against the state—pitiless, self-serving leviathan that it is. It’s like a Franz Kafka novel invading your home—except that Jewell himself cannot shake the naïve belief that the state is actually the good guy. He cooperates deferentially with the FBI guys while they are so clearly trying to railroad him. He’s forthcoming with them to the point of making his case harder to defend. This leads to some genuine humor when, after an exasperated Bryant warns Jewell not to say anything, he starts chatting anyway—all in attempt to make friends with his enemies.

But thanks to screenwriter Billy Ray’s sparkling dialogue, we know Jewell’s trust is misplaced. Early on, Bryant’s expat Russian wife and secretary Nadya (played by the stunningly protean actress Nina Arianda) says, “In my country, when the state says you’re guilty, that usually means you’re innocent.” Later, Bryant lets Jewell in on a secret. Shaw and his cronies “are not the government,” he says. “They’re just three pricks who work for the government.” Big difference.

The media represents another major theme in Richard Jewell. They’re like jackals. Or maybe piranhas. Or perhaps if we created a jackal-piranha hybrid in the laboratory, and then armed this new species of monster with cameras and microphones, then maybe we can approximate Clint Eastwood’s portrayal of the press in Richard Jewell. Led by an opportunistic, bird-flipping reporter named Kathy Scruggs (played forcefully and believably by Olivia Wilde), the local media run with the flimsy rumor that Jewell had planted the bomb. On the evening of the attack, Scruggs’ only concern is not to be scooped by her competitors. Later, she trades sexual favors for leaked information from Shaw and tries to do the same with Bryant. She also runs victory laps around her office when her misleading exposé is published. Only after it is too late does she realize the enormity of her sins.

It must be mentioned that the real-life Kathy Scruggs, who died in 2001, was nothing like this. Her former colleagues at the Atlanta-Journal Constitution have staunchly defended her and demanded the Eastwood print a disclaimer to this effect. I hate to say it, but Wikipedia says it the best:

Commentators noted that Wilde’s character was based on a real person, whereas the FBI agent was an amalgamation of multiple characters. They also noted that the purpose of the film was to expose and condemn the character assassination of Jewell. However, in the process, the film commits the same character assassination to Scruggs.

Leaving aside this valid complaint, the final conflict between Jewell and the FBI represents film at its absolute best. I’d call what follows a spoiler, but it really isn’t. Nothing this reviewer can write can do justice to this wonderful scene. Jewell is called in to the FBI offices to answer questions directly. After being strenuously warned by Bryant to say as little as possible, Jewell does what he always does, which is run his mouth. Only this time, he looks the beast in the eye and stares it down. Him—the overweight mama’s boy with the goofy mustache and the spotty employment record, staring down representatives of one of the most powerful organizations on the continent. It’s home cookin’ at its best. Jewell basically challenges Shaw to produce enough evidence to arrest him, and when Shaw doesn’t, Jewell declares the meeting over and walks out. If there’s a greater mic-drop moment in cinema, I’d like to hear about it.

Richard Jewell succeeds mostly through its scintillating script and superb casting. Eastwood’s direction (which I have always found lacking in vision) remains competent and admirably unobtrusive throughout. The same goes for the score. And say what you wish about Eastwood’s Lefty politics in the past, lately his films have offered a fairly staunch conservative voice in Hollywood. That the implacably corrupt villains in Richard Jewell are the deep-state government and the partisan media speaks much to the film’s Right-wing leanings. Some of Eastwood’s more subtle choices support this idea as well—such as having Jewell be a gun enthusiast who firmly disavows rumors of his homosexuality or having the camera repeatedly linger on the stars and bars appearing on the Georgia state flag. Mostly, though, Eastwood’s conservatism shines through in his choice of material. Richard Jewell is an almost entirely white film and is refreshingly—dare I say it—pro-white in outlook. The film actually drums up sympathy for white people who are pigeonholed in a negative way because of their race. You can’t get any more white bread than Richard Jewell and his mother. And you know what? That’s a good thing.

But it is good only as long we have octogenarian directors like Clint Eastwood wielding a modicum of power in a largely anti-white Hollywood. Once they’re gone and anti-white attitudes metastasize throughout the West thanks to mass immigration and demographic changes, directors of future pro-white films will find themselves to be greater underdogs than Richard Jewell himself.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

What White Nationalists Want from the Trump Administration Part 3

-

Joker: Folie à Deux – the Great White Nope

-

Fantastic Lies

-

Lucky for Some: John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13

-

Halloween Reading at Counter-Currents

-

Knut Hamsun’s Victoria

-

Road House 2024

-

Remembering Frederick Charles Ferdinand Weiss (July 31, 1885–March 1, 1968): Smith, Griffith, Yockey, & Hang On and Pray

8 comments

Eastwood’s former leftist politics? I was unaware of this. I’ve always thought he was more the mainstream Republican, vaguely liberal but hardly leftist.

I wish this film had a better title. I recall the movie John Carter (which wasn’t great on its merits) did poorly; its bland title was thought to have negatively affected its box office.

BTW, what do you mean about Clint’s lefty politics? The guy who starred in Dirty Harry, and made Josey Wales, and mocked Obama in front of everybody, can’t be that lefty …

Lord Shang and RVBlake,

Perhaps “lefty politics” was inaccurate and too harsh. Eastwood the man, politically, seems on the conservative/libertarian side of things. I was thinking of how, as a director or actor, he embraces multi-racialism in many of his movies. For example, he had a black girlfriend in The Eiger Sanction from the 1970s. If I remember correctly, in White Hunter Black Heart, his character chews out a woman for being knowledgeable about Jewish duplicity during World War I. In fact, this screed (again, if I remember correctly) wasn’t even crucial to the story, yet he said it anyway. Also, the way he casts Morgan Freeman so much doesn’t sit well with me. Invictus really made Nelson Mandela look good, if I am not mistaken.

I have not seen The Mule or Gran Torino, but will perhaps review them for CC in 2020.

But for all of this, Eastwood deserves credit for being one of most consistently conservative voices in Hollywood for many years. I would say he’s been mostly anti-anti-white. Richard Jewell is the first film of his that I am aware of that goes even beyond that into pro-white territory, although I have no idea if that was intentional.

Thanks.

I had forgotten about “Invictus” and what a cringe-inducing viewing experience that was.

Mr. Quinn,

You’re probably right. I’m no spring chicken, but Clint has been making movies for longer than I’ve been alive. Truly, a storied career. I’ve seen many, though not close to all, of his films, but have forgotten most of their details (as I often saw them once only and in the theater; plus, I’ve read, as an adult, over a thousand novels and short story collections, and seen several thousand films, so I have a lot of “fictive” memories to arrange and sort through). I suppose I could look at his Wiki page and really start recalling his offenses, film by film. INVICTUS was racially/ideologically subversive, as was MAGNUM FORCE, PINK CADILLAC and GRAN TORINO. UNFORGIVEN, a very well crafted film, imo, was also deeply subversive of traditional Western man – but I can see an opposing argument, too. A tough call.

Even JOSEY WALES was too sycophantic towards nonwhites. But how often have films portrayed a Confederate as the good guy, and the “blue coats” as the villains?

Also, just the mere presence onscreen of Clint himself (as with John Wayne) – a tall, capable, self-confident, All-American, Anglo-Aryan racio-cultural type – seems, at least retrospectively, implicitly counter-subversive to the “values” normally propagated by Hollywood in the postwar era.

I don’t think Clint is any kind of white nationalist at all, but I also wouldn’t quite call him “lefty”. I sense that personally he’s right of center, but more of a libertarian individualist with a pro-military and law + order bent, as opposed to any kind of race warrior (or Christian conservative). This, however, was a very common ethnopolitical type throughout the years of Clint’s acting prime (indeed, it sounds like many, many high quality whites I’ve known in my own life: capable white men, conservative politically, who were in no way ashamed to be white, but who also were truly colorblind {“blind to color and its realities”, as I think of it} and who treated nonwhites as individuals, without thinking too deeply about large numbers and their eventual effects), as well as one seen to be implicitly antagonistic to the subversive values and actions of our racial and (((ethnic))) competitor-enemies.

I cannot recall from his films that he was ever in your face anti-American. His films express love for America, but without any white racial animus against nonwhites (however much such animus is deserved). There is something tragically American about the type of white man that Clint seems to be personally – and certainly has portrayed onscreen (even Dirty Harry, if you recall, was alleged to be viewed as a “racist/fascist/militarist/sexist” etc, but in screen-fact was a basically racially tolerant guy who had a commonsense view (as Old Stock Americans would understand it) of the nature of criminals and the proper methods of dealing with them).

Clint’s strong, silent characters, who just go through life being stoic and tough and fair to others without thinking about “the bigger picture” or embracing any set of communal values, are sort of representative of the mental and cultural dislocatedness of even the best type of white man (the “normals”, as opposed to the white-guilt-liberals) in this postwar era.

“Rugged individualism” was a glorious aspect of our race, and did play a critical role in its ascension to global preeminence, but only insofar as such heroes and adventurers remained psychologically and institutionally tethered to their originating race and people. Clint’s characters actually seem to be a bit of a psychological bridge between the race-entwined white adventurers of the past, and the deracinated, atomized, and anomic white loners of today. We need white heroic individualists who are racially loyal, not ones just following their own codes, or only living for themselves. We need free-thinking and acting individual initiative contained within a larger racial survivalist boundary.

Might I be so bold as to suggest a topic for another of your columns? “A White Nationalist Looks at Clint”, or some such. It might take you a while, given his extensive oeuvre, but at least the “research” would be fun.

“A White Nationalist Looks at Clint.”

Oof. That’s a lot of movies to watch. Maybe over a series of articles something like that could be accomplished. Actually, I think you did a good job above. These righteous white loners are going to be a thing of the past pretty soon the way things are going.

Clint Eastwood has been anti-white since “The Eiger Sanction,” wherein he has a black girlfriend.

I was lucky enough to see the film Richard Jewell a couple of weeks ago – it is excellent.

It is an old fashioned morality play which pits good against evil and in which good at long last triumphs. The villains of the piece are undoubtedly the FBI who – as in so many other instances – frame an innocent man to suit their agenda, This was the case with Richard Jewell and has been the case many many times since – the case of Matt Hale is one that instantly springs to mind. And there are numerous others. And all this adds up to the sad fact that the FBI – far from being our defense – is ranked among our enemies, and that it will destroy us without remorse should the occasion arise.

Comments are closed.

If you have a Subscriber access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.