The poets and dreamers wove their magic webs, and a world apart from the world of actual experience came to life. But it was not all myth, nor all fantasy; there was a basis of truth and reality at the foundation of the mystic growth . . . — Jessie Weston, From Ritual to Romance

My friend said, what are you doing these days? I said, I’m working for Killing Joke. He said, Killing Joke? Are you mad? They’re evil. They’re devil-worshippers. — Chris Kimsey, music producer

Ritual has two forms, conscious and unconscious. Freud writes of unconscious ritual in The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, the quotidian repeat performances we all make. We talk of “our little rituals,” particularly if, as mine is, your life is affected to any degree by obsessive-compulsive disorder. These unconscious rituals are, I suppose, a sort of regulatory framework for our day-to-day lives, a comforting handrail on a ship which may pitch and yaw.

Then there is ritual in its religious or magical sense. This is still a regulatory framework, but it is conscious, communal, and managed precisely, with great attention paid to detail. The ritual can be intended to worship, to summon, to appease, or to petition, and any deviation from its exact commission will end in failure. A ritual always asks for a manifestation, be it harvest or demon, and a magical ritual in a dismal London apartment in 1979 had a very specific manifestation: Killing Joke.

Born out of ceremonial magic at the start of what became known as post-punk, Killing Joke stormed in with an air of menace which was genuine, not the greasepaint shtick of Bauhaus. For a start, Killing Joke were one of those English bands of that time who looked like they might beat you up (see also Dr. Feelgood and The Stranglers). The menace wasn’t just physical, though; it was also metaphysical.

I don’t know if America has “Marmite bands,” named for the tangy vegetable spread which, when served on toast, divides the British into disgust or affection. Curiously, many English Marmite bands from the turn of the 1980s were from Manchester. Maybe there’s something in the Mancunian water. The Smiths, The Fall, and Joy Division inspired in their listeners either sneering cynicism or a near-religious reverence. So it is with Killing Joke.

The Joke, as fans refer to the band, are a standard rock four-piece: vocals, guitar, bass, and drums, with some one-note Moog synthesizer as a backdrop on early recordings. The music is raw, primal, and often grandiose. Drummer Big Paul Ferguson, a confusingly slightly-built man who was one of the instigators of the ritual that spawned the band, is a tub-thumper with the rhythmic nous to add a tribal signature. Bassist Youth, formerly in a band with John Lydon’s brother Jimmy, has a distinctive bass style. An aficionado of dub reggae, his playing incorporates the gaps and spaces reggae bassists use to create an area for the other sounds to move in without directing the melody or rhythm itself. Geordie Walker is an extraordinary guitarist (and an accomplished drinker, of which more later). Vocalist Jaz Coleman has this to say about him: “The sound that comes out of this man Geordie’s guitar strikes fear into every other guitarist on the planet. It’s like fire from heaven.”

But Killing Joke has always revolved around its singer, who drummer Paul describes as “a reluctant front man.” Part musician, part mystic, part maniac, Jeremy “Jaz” Coleman could be seen as more sham than shaman. That, as we shall see, is part of the point.

Coleman was born in 1960 in the rural English town of Cheltenham. His father was English, his mother Anglo-Indian, and Coleman’s features show his lineage. As a child he sang in cathedral choirs and was taught violin by a schoolteacher, and while he has never attended music college proper, his travels have been for the sake of musical — and existential — self-education, a virtue he espouses. His study of the Arabic quarter-tone system would emerge in his later solo work, and even echo in Killing Joke. His musical career outside Killing Joke includes symphonies, orchestral settings of Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and The Doors, and various classical and Arabic collaborations.

After the band’s fiery inauguration — they burnt down Paul Ferguson’s apartment during the ritual –, success came quickly. Punk was not only dead, but the corpse was beginning to smell. The British music press needed fresh meat, and they got it, sometimes literally. The music press was very powerful and influential just then in the United Kingdom, and enthusiastic about Killing Joke’s unrelenting sound and attitude. John Peel, the guru of British indie music, praised them to the roofbeams, partly beguiled by their tightness as a unit. Killing Joke’s eponymous first album was followed by critical success What’s THIS For . . .! before the crucial third album, Revelations, gave the band their biggest hit, the Yukio Mishima-inspired Love Like Blood.

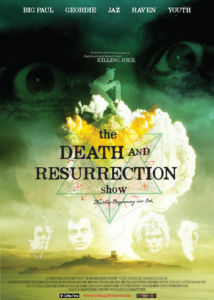

If you are a fan of Killing Joke, you will have seen The Death and Resurrection Show, a 2015 documentary about the band and a brilliant directorial debut by Shaun Pettigrew. If you should watch it, then you will be watching not just a brutalist and fascinating rockumentary but one with a very definite sub-text: magick. I use the Crowleyan spelling there, as it has the specific meaning of ritual magic, occult theory elevated to the realm of practice. All four of the bands have magical interests, and Killing Joke itself emerges from the film as a magical project, with all the tempestuous results any summoning can have if great care is not taken.

You can buy Mark Gullick’s Vanikin in the Underworld here.

Magic is a difficult subject to broach. Cynicism comes naturally to those who know magic only as a long-vanished period in mankind’s childhood or as a form of modern entertainment. Coleman has devoted most of his adult life to magick in one form or another, and if you incline towards the cynical, you will be sneering and cawing for at least half of this 150-minute film. If you are interested in the occult, then this is the testament of a magical work in progress. For me, if the end result of all the rituals and the numerology, the Kabbalah and the gematria, and all the rest of Jaz Coleman’s occult mental furniture — if the end result of all that is Killing Joke, then magic works, if works is the word.

Coleman has tried the patience of his fellow band members over the decades, and it has nothing and everything to do with the dark arts. The band were booked in for a key TV appearance in 1982 and Coleman didn’t show up. Instead, a letter arrived at the stage door explaining why Jaz had to be somewhere else. He disappeared and turned up three days later in Iceland, having gone there because he believed the world was about to end. Coleman is a geomancer, among other things, and the configuration of ley lines in Iceland, he explained, made it a propitious place to be for this imminent Ragnarök. Geordie eventually followed him, followed by Youth, leaving Big Paul alone and betrayed. And something else happened in Iceland.

Death and resurrection. Resurrection is habitual with this band, partings and returnings being a regular feature of Killing Joke, and the arguments usually being bitter, vindictive, and often violent. What of death? It is a constant reference point in Coleman’s more abstruse pronouncements and there are three deaths in the film, all of which have a somber place in what director Pettigrew calls “the Joke’s roadside of destruction.”

Paul Raven became the bassist for Killing Joke when Jaz and Youth had acrimoniously, and apparently finally, parted company. He was a natural for the band and formed a particularly strong bond with Coleman. In 2007 Raven left to join heavy grunge outfit Ministry. Coleman was livid: “If we ever meet again, one of us dies.”

They did meet again, restored their friendship, and Raven recorded with the band in 2011 in Geneva. Then he died of a heart attack at the age of 46. Despite being a notorious hell-raiser, Raven still seemed the latest fatality of the Killing Joke curse. But he was not the first.

When Geordie had joined Jaz in Iceland in 1982, the pair took part in an occult ritual. Two girls were present: English occult student Sarah Parkinson and the sister of Jaz’s Icelandic musician friend, Guðlaugur Kristin Óttarsson. Pettigrew gives the only information I can find on what happened next, and makes this eerily vague comment:

Press cutting and research leads her [initiate journalist “Jana”] to a disturbing but secretive incident in Iceland in 1982 when two women, Vivan Ottis Dottir and Sarah Parkinson, eventually died after some mystical occult ritual attended by Coleman and Killing Joke band mate Geordie. It becomes clear that the Iceland affair was indeed misunderstood, Iceland or rather the “island” as perceived by the band had a much deeper significance than just a geophysical reality, it was a thought-form that they charged regularly through ritual catharsis.

And that’s it. I can’t find Jana’s research or any other mention of the deaths online. Admittedly I wasn’t deep searching, but nothing? The girls are there at the ritual, they die later, and we’re back to Jaz talking about archetypes and the cosmic soul. Coleman looks perturbed and preoccupied when he touches on the incident in the film. One of Killing Joke’s earliest successes was a song called “Requiem.” It is more than Parkinson and Dottir got in this documentary. But the film, and the saga of Killing Joke, continues. The dog barks, the caravan moves on . . .

Pettigrew understands the three main principles of Killing Joke: music, magic, and laughter. He also understands the polarities at work, and how they can switch unexpectedly. Glibly describing the film as “The Da Vinci Code meets Spinal Tap,” the director also shares many of the band’s magical beliefs.

But Killing Joke’s growing reputation for being the bringers of malevolent forces to rock music meant that they had to continue making music, and 1993 saw one of their many resurrections, and certainly the most spectacular. There have been some memorable makeshift recording studios in rock and roll history. The Stones recorded Exile on Main Street in a French farmhouse. The famous drum sound for Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks” was captured by setting up John Bonham’s drums in the cavernous hall of a mansion called Headley Grange. Pink Floyd famously played and recorded in the amphitheater of Pompeii. But Jaz Coleman wanted to go one better for Killing Joke’s 1993 album Pandemonium. They recorded it in the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramids at Giza.

The pyramid sessions are a great passage in the film not just for the arrogant brilliance of Coleman’s vision, but the Killing Joke elixir of music, magic, and laughter. It shows the band’s deep attachment to ritual magic and geomancy, Coleman’s persona as the trickster god, the jester and harlequin he often imitates, and the majesty of Killing Joke when they are attuned and playing hard and remorseless rock. Pandemonium might be the band’s masterpiece.

According to Jaz, the interview for permission to record on the sacred site consisted of the chief curator asking him if he was a Satanist. The way Youth tells it, Coleman just slapped three grand US on the table and the deal was struck. Either way, the recording sessions left the locals with mixed feelings. One sound engineer thought the band had achieved something magnificent and Egyptian, another had a kind of breakdown at the sessions and thought the Eye of Horus was chasing him. He says bitterly that the band would never again be allowed in the pyramids.

The 1990s move on, and with it Coleman’s solo career, both in music and magic. Jaz’s mother makes a delightful cameo, and the scene of Lord of Chaos Coleman making her a cup of tea in her chintzy front room is hilarious. An elderly lady who looks like she could work as a camera double for the Queen, she says of Killing Joke’s album Brighter than a Thousand Suns (one of their worst, in my view), “Ooh! That’s the one where Jeremy learned to sing!” She also makes a royal pronouncement in the context of the movie; “Jeremy has a great fear of something.”

Coleman also compels other musicians to work with him, like it or not. While the Joke are commended by Coleman’s friend Jimmy Page, Joy Division’s bassist Peter Hook also features in the documentary and does nothing but jibe and ridicule Coleman every time he’s onscreen. Hook on Killing Joke’s occultism: “Who gives a fook? I’m from Salford [a tough suburb of Manchester]. Who cares about the fookin’ devil?”

But Hook has recorded with Jaz and Geordie as K÷93. Killing Joke and their various musical offshoots form a very tangled family tree, and one of these collaborations in 1999 would spark a controversy that seems quaint to us now for one very specific reason.

Rugby Union has always been huge in the UK, and the World Cup final of 1999 was played at Twickenham, the sport’s global home. Killing Joke had recorded an album in Auckland, New Zealand and Jaz had arranged a version of the Kiwi national anthem to be performed at the opening ceremony which featured a Maori woman singing the second verse in the indigenous language. Thousands of fans booed. The head of Rugby Union (not to be confused with Rugby League) asked Jaz to change it before the performance and he refused point-blank. Coleman ended up being interviewed by Jeremy Paxman, who is the equivalent of David Letterman but with a plummy English accent, who asked the singer why he would want to antagonize people so much. Today, if the whole thing wasn’t done in Maori there would probably be a similar uproar.

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here.

After the furor, which embittered Coleman, he retreated to Prague where not much happened except for his being asked both to accept the post of composer-in-residence with the Prague Symphony Orchestra, and to make his conducting debut with the same. This is the same man who once read a negative review of Killing Joke, went to a butcher’s shop and bought a huge piece of bloody and dripping liver, visited a fishing-tackle shop to pick up a tub of live maggots, then on to the magazine’s offices to dump the lot on the reception desk, into which he stabbed a pair of scissors for good measure. A mass of contradictions, an obvious charlatan, or just a man who has found different ways to channel magical energy? You decide.

As well as being what Coleman calls “a Mecca for great composers such as Mozart and Beethoven,” Prague was also the birthplace of Rosicrucianism, the esoteric fraternity said to be the Secret Chiefs of the World. The idea appeals to Coleman, developed as it was by Aleister Crowley and McGregor Mathers at the Order of the Golden Dawn. Coleman talks a lot about grand cosmic design, ley lines, grid points, alien architecture, and geomancy. “Jaz’s mind,” says someone, “is more dangerous than a computer.”

Watching Coleman, this arrogant Renaissance man who initially didn’t want the film to feature the rest of the band, prompts the question of whether this is a bit of a put-on, a bit of an act. He is clearly as mad as a box of frogs, but for me he shines with authenticity. Magic is abstruse, but it is also absurd. One bar scene features an increasingly drunk Jaz, dressed in a vicar’s habit and collar and fresh from preaching at the Church of Killing Joke (partly in Latin), explaining references to UFOs in the Old Testament to Dave Grohl. Coming from Coleman, it seems as natural as two men discussing last night’s game.

Humor is a key ingredient to the magic. Geordie seems the least inclined to the occult in Killing Joke, but his trip to Iceland with Coleman obviously did move his mind to another place or plane. That doesn’t stop him poking gentle fun at his co-conspirator, however, as in this radio interview:

JAZ: We’re like Hawkwind.

GEORDIE: No, we’re not.

JAZ: You’re a cruel and embittered man, Geordie.

GEORDIE: Put a spell on me then, you wally.

The periods of inactivity began to wear on the founder members, but they turned elsewhere. Paul Ferguson took up his hobby of art restoration, and Youth was persuaded to become a producer. It was Youth who organized the ritual which kick-started the Pandemonium sessions in the King’s Chamber, and he transferred his occult skills to the mixing-desk, producing The Verve’s massive hit album Urban Hymns and its two number one singles. He produced Paul McCartney and generally made a lot more money than he ever had with Killing Joke. But he still went back; they always go back to Coleman the enchanter.

If I said that Killing Joke’s one big hit, Love like Blood, got me drunk, I might be accused of Romantic hyperbole, but it really did. In the springtime of 1985 I was living in the university town of Brighton, and one evening I wandered into a bar. Roll-neck sweaters were the big thing at the time, and I was sporting a rather snazzy black one. I got a nod of sartorial acknowledgment from a guy at the bar: tall, formidably cheek-boned, and wearing a white roll-neck. He had a magnificent blond rockabilly quiff and I recognized him at once as Geordie Walker.

We struck up a conversation and he bought me drinks all evening, a hilarious jumble of music and trash talk. We were drinking Pils, the diabetic beer in the brewing process of which all the sugar turns to alcohol and the next morning I didn’t feel like listening to Killing Joke. At one point I told Geordie I though Jaz was quite a fan of Nietzsche. “Yeah, I think he read the back of a Penguin paperback by him.” He wouldn’t let me buy a beer, claiming the band had received royalties for the first time ever, and this was money earned from Love Like Blood.

I’ve seen the band three times, but the first was the best. It was 1981 on the campus of my university. When the band were ready to go on, instead of just the house lights dimming, the entire place was plunged into darkness and Killing Joke appeared from the back of the hall, their company carrying blazing torches as they parted the crowd and made for the stage, Jaz in his trademark daubed face-paint, like Brando and Sheen at the end of Apocalypse Now. These weren’t tiki torches for a beach party, either; you could see the fat spitting out from the flames. They were very, very good live. Killing Joke just crush you, then uplift you, then crush you again.

Finally, throughout the turbulence of Killing Joke, Coleman kept one magical goal clear in his mind: an island called Cythera. Rock stars are always buying little oceanic hideaways for their yachts, but this being Jaz Coleman, the island had to tally geographically — and thus geomantically — with islands mentioned in Dante’s Inferno, Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis, Aleister Crowley’s Book of the Law, and the strange book by Fulcanelli, Le Mystére des Cathedrales. I say it’s a strange book, but I have never read it. I ordered it from Watkins Occult Bookshop in London’s Cecil Court ten years ago and, by the time I left the country six years ago, it still hadn’t arrived. Perhaps the Secret Chiefs don’t want me to read it. They wanted Coleman to find his island, though, and he did.

Whether the peace of a spiritual island retreat will be enough for Coleman, I can’t say. Watching him reel around drunk in this movie, knowing the legendary reputation Killing Joke have for drink and drugs, you compare this occultist maniac with the Coleman who, in 2010, was made a Chevalier des Artes et Lettres, a French order ordained to celebrate great but maverick art. Former Chevaliers include William S. Burroughs, Rudolf Nureyev, and Philip Glass.

I would like to know the reaction to this movie of someone who had never heard a note by Killing Joke. On one level, it is the story of a ramshackle bunch of near-lunatics, hopped up and on acid, who decided to take out their frustrations in a hard rock band. On another, is it a complex magical work which has to be admired and applauded.

If Killing Joke are the manifestation of a magical ritual, then magick works. And as for Jaz Coleman, we’ll leave the last word to his friend Jimmy Page, who once bought Aleister Crowley’s old house, Boleskine. Page has no doubt about Coleman; “He’s either playing with magick, or magick’s playing with him.”

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Killing%20Jokeand%238217%3Bs%20The%20Death%20and%23038%3B%20Resurrection%20Show

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

13 comments

Must procure. I’ve only ever (knowingly) heard “Love Like Blood”, but love that song.

Random high-school memory: 6’+tall guy used to wear Killing Joke t-shirt all the time; he’s (she’s) now a professional fully transitioned female racecar driver.

What a fascinating article.

Just finished watching it. Very interesting.

I recommend Coleman‘s book „Letters from Cythera“. I did not understand a word in it, but it changed the direction of my life, it really did.

The film is supposedly based on that book.

It is a good film, I wouldn‘t say it is based on the book. The book is part autobiography, as one would expect, part theoretical esoteric treatise, complete with very beautiful cabbalistic/alchemist diagrams I was quite surprised how deeply the band members are interested in the esoteric, how knowledgable they are and how much of it they incorporated into their albums and artwork. I don’t get all this esoteric side at all, but I love that band very dearly.

Excellent taste once again. I was first introduced to Killing Joke via a few boomer coworkers at a graphic design studio I interned at, one of whom had a penchant for playing Love Like Blood. As a millennial I was mostly into bands like Interpol and Franz Ferdinand at the time (and thankfully just coming out of my Muse phase) but already well into darker bands like Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds and Bargeld’s Neubauten, I felt in Killing Joke a uniquely English form of this musical darkness that was immediately attractive to me. Anyway, before I start blogging, here’s a few of my favorites.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sk0TsOwIceI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U7WPI4TJImo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qOP7UAbeQM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jE8AInkhE7s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TgYiPw6EgDs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozmtBfNBkXg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bRv5MFipqwU

Watched this last night. Thanks for the recommendation. Not a band whose work I was familiar with except, of course, Love Like Blood. The music of theirs they played in the film sounded like bog standard 80s goth to me.

Jaz Coleman seemed like a total prick and nutcase, and you wondered how much of the ‘pained musical shaman’ schtick was put on for the camera or music press of the time. He clearly did believe in all that occult rubbish, mind you.

The most interesting part was him going to Egypt and recording in the pyramid. That bit was fascinating, and seemed, to me, like the only time he was a useful musician and human being. Clearly some sort of genuine blood-buried classical musical talent there. The doc was worth a watch, though it didn’t make me want to go and check out any more of the man’s work, except the pyramid stuff. I will definitely give that a listen, and read more about that part of the story.

I really liked your comment. I am trying to work through magic as just idiots showing off. ‘Bog standard eighties Goth’ is my phrase of the month. Sisters of Mercy? Bog standard eighties Goth, mate.

I love Lucretia, My Reflection, though, both the song and video. The video seems to have been filmed in India but I’ve been unable to find any info on the making of the video.

I read this while swilling the house brew in a tavern in Salem, Massachusetts. Karma or coincidence?

Never heard “Love Like Blood.” Heard “The Wait” because it was covered by Metallica in 1986 or 87. That really boosted Killing Joke in the U.S. Metallica’s covers EP was very influential and every band they covered on it was lucky to be on it. Budgie and Diamond Head as well as Killing Joke were introduced to me by that EP. I wish more bands at the peak of their careers had done what Metallica did with that EP. Bowie did it also, but I can’t think of others right now.

Great article about my favourite band! Sorry to be a bit nerdy, but I spotted a mistake: Love Like Blood is not from Revelations, but from Nighttime, their fifth album, so from a somewhat later period. Seen them six times myself, and the last time I had the courage to go and talk to 3/4 of them, namely Youth (at their t-shirt stall before the gig), Geordie (briefly just after the gig in the hallway), Jaz (longer discussion in the bar afterwards). None of them beat me up despite myself being near legless at the time. Great gentlemen all three. And great humorists too.

Is this a joke?:

“In 2007 Raven left to join heavy grunge outfit Ministry. Coleman was livid: “If we ever meet again, one of us dies.”

They did meet again, restored their friendship, and Raven recorded with the band in 2011 in Geneva. Then he died of a heart attack at the age of 46. Despite being a notorious hell-raiser, Raven still seemed the latest fatality of the Killing Joke curse. But he was not the first.”

So, an old eventually dies of a heart attack. The fact that you attribute this to magic makes me doubt the veracity of the next account of the two girls too. Come on, man. Use some thinking here.

Comments are closed.

If you have a Subscriber access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment