The Populist Moment, Chapter 12:

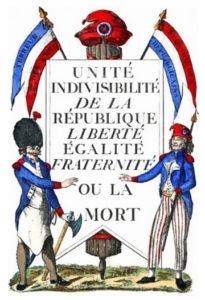

Liberty — Equality — Fraternity:

On the Meaning of a Republican Slogan

Alain de Benoist

Introduction here, Chapter 11 Part 4 here

Translated by F. Roger Devlin

As is well-known, the republican slogan “Liberty — Equality — Fraternity” was first invoked during the French Revolution.[1] At that time it was merely one slogan among many others. Falling into disuse under the Empire, and frequently called into question thereafter, it reappeared during the Revolution of 1848 when it was inscribed as a “principle” of the Republic in the Constitution of February 27, 1848. We run into it again in many socialist theorists of that time, such as those of Pierre Leroux and Louis Blanc. But it only finally succeeded in imposing itself in the age of the Third Republic. For the July 14 celebration of 1880, it was decided to inscribe the slogan on the pediments of public buildings. It was thereafter inserted into the Constitution of 1946 (the Fourth Republic), as well as that of 1958 (the Fifth Republic).

For two centuries, these three concepts have not ceased to be the object of intense debate.

The compatibility of liberty and equality were not at first contested. Under the Revolution, liberty was often perceived as a perfectly natural means of assuring equality, the latter conversely being considered as engendering liberty thanks to the power of the law. Later, an author such as Pierre Leroux — who coined the term “socialism” — tried to evade difficulties by making liberty a goal of which equality was the principle and fraternity the means. These conclusions were soon questioned, however. Equality and liberty were posited as relatively antagonistic to one another. This opposition further increased when equality was redefined not as equality of rights, but as equality of results; the idea then spread that such equality involved a certain coercion limiting liberty (whence liberals’ distrust of equality). Conversely, liberty was regarded as susceptible of giving birth to new inequalities (whence socialists’ distrust of liberty).

A whole dialectic was then established between the two concepts. Some authors, for example, made each of these two terms the means for preventing the other’s excesses. Liberty would limit the tendency towards levelling implied by equality, while equality would limit an excess of liberty leading towards intolerable hierarchies. But from a different point of view, it is the slogan’s third term, fraternity, which appeared as a means of reconciling the other two, and secondarily of reconciling their respective defenders as well. In other words, to fraternity was entrusted the means of conciliating, and at the same time transcending, equality and liberty. This transcendence could be compared to a Hegelian Aufhebung, with fraternity playing the role of synthesis in relation to the thesis liberty and the antithesis equality.

The three concepts have also been placed in chronological order. Men at first demanded liberty, then demanded equality, after which their aspirations turned to fraternity. Victor Hugo made of fraternity the “final step” which could only be attained once the other two had been reached. This interpretation corresponds to the slogan’s formulation, in which fraternity does in fact come last. But some authors proceed in the opposite direction, defining fraternity as the necessary condition for the establishment of liberty and equality within a political society.

* * *

If we want to speak coherently about the republican slogan “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” the first thing we must understand is that it is a political slogan. This means that it is the political (and not the general, symbolic, moral, etc.) meaning of each of these concepts that must be taken into account: political liberty, political equality, political fraternity. To pass from political freedom to economic freedom, for example, or to confound political equality with natural equality, or political fraternity with moral fraternity, represents a serious misinterpretation.

Here we shall limit ourselves to equality and fraternity, for it is regarding these two concepts that there exist the greatest number of misunderstandings.

The equality between A and B (A = B) means either that A is similar or identical to B — i.e., no different from it — or that they are equivalent according to a specific criterion and in a determinate relation. Then one must specify this criterion or identify this relation. “If there is only equality in a determinate relation,” writes Julien Freund, “the same beings and the same things can be different or unequal in other relations.” It follows that equality is never an absolute given and that it does not refer to an intrinsic relation, but depends on a convention — in fact, on the criterion used or the relation chosen. Stated as a self-sufficient principle, it is empty, for there is no equality or inequality except in a given context and in relation to criteria allowing it to be concretely posited or appreciated. The concepts of equality and inequality have thus always been relative and, by definition, are never without their arbitrary aspect.

As for democratic equality, so poorly understood for various reasons on both the Left and Right, it must be understood first of all as an intrinsically political concept. Political equality no longer signifies merely that in a democracy the law is the same for all, independent of distinctions of birth or origin. It is above all a characteristic, a prerogative shared by all the citizens. All citizens are politically equal not because they are similar or “naturally” equal, but because they are all equally citizens.

Democracy thus implies the political equality of citizens, and not at all their “natural” equality. As Carl Schmitt remarks:

The equality of everything “with a human face” cannot issue in a State, nor a form of government, nor a governmental form. We can draw from it no distinctions or limitations. . . . From the fact that all men are men we cannot deduce anything specific, neither in morality, nor in religion, nor in politics, nor in economics. . . . The idea of human equality furnishes no legal, political, or economic criterion. . . . An equality which has no other content that the common equality per se of all men would be an apolitical equality, for its lacks the corollary of a possible inequality. Every form of equality draws its importance and meaning from its correlation with a possible inequality. It is all the more intense the more significant is the inequality with respect to those who are not among the equals. An equality without possibility of inequality, an equality one possesses intrinsically and that one can never lose, is without value and a matter of indifference.[2]

Like any political concept, democratic equality refers to the possibility of a distinction. It sanctions a common belonging to a particular political entity. The citizens of a democratic country enjoy equal political rights not because they have the same competences, but because they are equally citizens of their country. Similarly, universal suffrage is not the sanction of an intrinsic equality of the voters: The real democratic principle is not “one man, one vote,” but “one citizen, one vote.” As we have already said, it is the logical consequence of the voters all being citizens, and its function is to express their preferences and to permit their disagreement or consent to be recorded. Political equality, the condition for all the other forms (in democracy the people represent the constitutive power), is in no way abstract; it is altogether substantial. Already among the Greeks, isonomia did not mean that the citizens were equal in terms of competence, but that all had the same right to participate in public life. Democratic equality thus implies a common belonging, and thereby contributes to define an identity. This term “identity” refers both to that which distinguishes, singularity, and to that which allows those who share this singularity to identify with one another collectively.

The first consequence of this is that “the essential concept of democracy is the people and not humanity. If democracy is to remain a political form, there are only democracies of the people, and no democracy of humanity.”[3] The second consequence is that the corollary of the equality of citizens resides in their non-equality to those who are not citizens. Carl Schmitt writes:

Political democracy cannot rest on the absence of distinction between all men, but only on belonging to a specific people; such belonging can be determined by quite diverse factors. . . . The equality which is part of the very essence of democracy thus only applies within a State and not outside it: within a democratic State, all citizens are equals. A consequence for politics and public law is that he who is not a citizen has nothing to do with that democratic equality.[4]

It is in this respect that “democracy as a principle of political form is opposed to the liberal ideas of the liberty and equality of each individual with every other individual. If a democratic state recognized universal human equality in the domain of public life and law down to its ultimate consequences, it would rid itself of its own substance.”[5]

You can buy Alain de Benoist’s Ernst Jünger between the Gods and the Titans here.

What about the concept of fraternity?

Fraternity, from the Latin frater, “brother,” originally designated a natural — not to say biological — bond. The term fraternitas did not appear, however, until the second century and in Christian authors. But its political meaning is quite different; in certain respects, even opposed. In the political sense, fraternity refers to an existing bond (or a bond one wishes to see exist) between the members of a single organization or a single community of reference, between those who share the same ideal or who defend the same cause, and by extension between those who belong to the same political entity. Fraternity thus appears indissociable from citizenship. In the political sense, it expresses the bond which ought to unite all citizens.

If the term fraternity has often appeared problematic, this is precisely because people have wanted to give it a universal character or moral scope (“all men are brothers”) which directly contradicts its political usage.

Political fraternity has nothing natural about it. Not only does it not consist in considering all men brothers, and that they are members of the same family, but it is an elective solidarity: It consists in recognizing as brothers people who do not belong to our family, and doing so merely because they are fellow citizens. Fraternity is not the same as siblinghood [fratrie], as Régis Debray rightly noted when he wrote: “Fraternity is the contrary of consanguinity; it is the remedy for siblinghood. . . . For me, there is fraternity from the moment one breaks the circle of the family, the prison of natural communities, and when one gives oneself an elective family, which is a transnatured, if not denatured, family.”[6] In political fraternity, one is only born a brother because one was born in the same political society. And this fraternity extends to all temporal dimensions: It associates the dead and the living. Let us cite Régis Debray once more: “Since peoples, like individuals, are composed as much of the dead as of the living, how can the living be respected if one is not the dead’s younger brother?”[7]

Fraternity is not identical with friendship. While friendship is a durable sentiment, a permanent bond that is in some sense static, fraternity asserts itself mainly in reference to a context, an event, a struggle. Like solidarity (which it transcends by adding the affirmation of a principle), it is a response to a situation. It asserts itself by way of opposition. It transforms occupation into resistance, humiliation into pride. It thus possesses a more dynamic character. It is also more collective, more “popular” than friendship which, because if its personal character, rather favors elitism. It is in this sense that Régis Debray was able to describe fraternity as a “modern and democratic sentiment,” also emphasizing that fraternity cannot be defined as a pure sentiment insofar as it is often indissociable from praxis, from action (“friendship lulls, fraternity shakes”).

But this is also the reason fraternity separates as much as it joins. It has indeed been said that political fraternity does not associate all men. On the contrary, it establishes a dichotomy between those who are regarded as brothers and those who are not. It integrates the former, while it excludes the latter. Fraternity, in other words, defines a collective us by way of opposition to those who do not belong to this us, and which it keeps at a distance or places apart. It gives this us the possibility of forming a single body [faire corps]. But there is no us without a them. Régis Debray declares in principle that “fraternal communities, born of adversity, have difficulty doing without adversaries.”[8] The best proof is that one never fraternizes so well as when one fraternizes against a common enemy. This is also what Robespierre said:

Fraternity is the union of hearts, it is the union of principles: the patriot can only ally himself to a patriot. . . . When a people has established its liberty . . . when its enemies are reduced to an inability to harm it, the moment of fraternity has arrived.

Here we must also remark that there exist certain differences between the nature of fraternity and that of the other two concepts of the republican triad, equality and liberty. The first difference is that liberty and equality can be posited as rights to conquer: We have a “right to liberty,” a “right to equality.” Liberty and equality can be specified as well: liberty of expression, equality of opportunity, etc. Fraternity has no genitive case: It is less a right than an imperative; indeed, an obligation. One fights for or against liberty and equality, which explains why they can be separated from one another when their defenders and opponents enter into confrontation. Fraternity, on the other hand, reconciles. It unites insofar as it constitutes an obligation of all to all, of each to another.

Another important difference is that equality and liberty can be posited as prerogatives applicable only to individuals. They can for this reason become individual values. Fraternity, on the contrary, by definition implies a community or collectivity. It is an encompassing concept by the same title as Aristotelian “friendship,” which it closely resembles, and by the same title as well as the ancient concept of the common good. Fraternity, in other words, cannot be distributed: It is an indivisible good all the citizens enjoy in common and immediately, in an almost fusional manner. This good is an attribute not of the individual, but of the social and of sociability: There is no fraternity of a single person. It is significant in this respect that a number of liberal authors have accepted the concepts of liberty (transposed into individual autonomy) and equality (limited to equality of rights) while professing a certain distrust of the “collectivist,” “socialist,” or “holistic” concept of fraternity.

In his speech of November 15, 1941, Gen. de Gaulle declared: “We say Liberty-Equality-Fraternity because our will is to remain faithful to the democratic principles which our ancestors drew from the genius of our race and which are at stake in this war for life or death.” We can add that at a time when we witness an increasing disaggregation of the social bond, only the concept of fraternity can allow the recreation of a collective us and reanimate a collective project abandoned by the me. In the past, popular democracies appealed to equality, liberal democracies to liberty. Organic democracy, founded on the participation of the greatest possible number of citizens in public affairs, should above all be based on fraternity.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] It was in December 1790, in his Speech on the Organization of the National Guards, which was never delivered but widely distributed throughout France that Robespierre demanded that the words “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” be inscribed on uniforms and flags. This project was never adopted, however. The following year, in May 1791, we find the same triad in a proposal made at the Cordeliers Club by the Marquis de Guichardin. Cf. Mona Ozouf, “Liberté, égalité, fraternité,” in Pierre Nora (ed.), Lieux de mémoire, vol. 3: La France. De l’archive à l’emblème (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), Quarto series, 4353-4389; and Michel Borgetto, “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” (Paris: PUF, 1997).

[2] Carl Schmitt, Théorie de la Constitution, tr. Lilyane Deroche (Paris: PUF, 1993), 364-365.

[3] Ibid., 371.

[4] Ibid., 365.

[5] Ibid., 371.

[6] Régis Debray, “Les miens et les nôtres,” in Le Nouvel Observateur, April 16, 2009, 90.

[7] Régis Debray, Le Moment fraternité (Paris: Gallimard, 2009), 351.

[8] Ibid., 324.

The%20Populist%20Moment%2C%20Chapter%2012%3A%0ALiberty%20and%238212%3B%20Equality%20and%238212%3B%20Fraternity%3A%0AOn%20the%20Meaning%20of%20a%20Republican%20Slogan%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 3

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Democracy: Its Uses and Annoying Bits

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

Bottled Up

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej