3,251 words

Libertarianism can elicit strong reactions from dissidents these days, largely because it has been such a common gateway drug for the Right. Many white identitarians today came of age as libertarians, and so have intimate knowledge not only of that marvelously balanced and consistent belief system, but of all the reasons why they ultimately abandoned it. Libertarianism, despite its virtues, has nevertheless proven inadequate as a political ideology, and is therefore a recipe for defeat for those who wish to stem or reverse the rising tide of the Left. This does not mean, however, that libertarianism should be abandoned completely. Its precepts should never leave the economic arsenal of any modern civilization that wishes to prosper. People should not blind themselves to this and fall for the specious notion that because libertarianism cannot take us to the Promised Land, it can therefore take us nowhere.

Free to Choose, the 1980 “Personal Statement” by Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman and his wife Rose, offers an excellent beginner course on libertarianism, complete with examples, thought experiments, and theoretical underpinnings. As far as literature-as-persuasion goes, it’s first rate; at times brilliant. Friedman has a philosopher’s mind as he manipulates different ideas within a unified logical framework. But just as libertarianism fails to incorporate certain crucial aspects of the human condition, so does Free to Choose. Human beings are so much more than mere economic actors, and no, political systems should not be treated as markets.

From the beginning, Friedman adheres to the tenets found in Adam Smith’s 1776 treatise The Wealth of Nations. Friedman provides an adequate rundown of the basics of economics and deftly argues how crucial individualism and liberty are for successful societies. Economic freedom, for Friedman, is a prerequisite for political freedom — and he’s not wrong. Libertarianism relies on using the “uniform, constant, and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition,” in the words of Smith, as the engine for economic growth and prosperity. This is a natural — and therefore superior — alternative to top-down, centralized efforts to control economies in the name of some ideal, usually egalitarianism of some sort.

In his Introduction, Friedman expresses his goal in Free to Choose thusly; note its modesty:

We have the opportunity to nudge the change in opinion toward greater reliance on individual initiative and voluntary cooperation, rather than toward the other extreme of total collectivism.

You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s Solzhenitsyn and the Right here.

Because Free to Choose presents libertarianism as a complete political ideology, however, it revisualizes human nature almost at the cellular level. Friedman proposes a radical departure from the paternalistic socialism prevalent among twentieth-century Western thinkers to less mainstream, yet principled individualism — a leap that many have found to be a bridge too far. But Friedman’s admission is quite telling. When viewed as a mere suggestion for people who are already in power, Free to Choose retains great value; when viewed as a political philosophy for people who wish to gain power, not so much.

Using the idea of a pencil’s life cycle, Friedman illustrates two of his primary ideas in Free to Choose: interconnectivity and the functions of prices. This common utensil made of wood, metal, graphite, and factice (the material used for erasers) depends on an astonishing confluence of raw materials, manufacturing, transportation, and marketing — all of which are determined by prices. A shortage of a certain raw material, a railway strike in a certain area, severe weather conditions, or an innovation in a competing utensil such as pens could impact the balance of supply and demand and drive the price of pencils higher or lower for a time. Friedman’s point is that prices tell us something about the interrelatedness of the myriad of happenstances that go into making any number of items that you and I can find almost anywhere. When government artificially controls prices in reaction to, say, geopolitical events or to curry favor with constituents, such as through tariffs or price freezes, they are interfering with prices’ ability to convey accurate information and incentivize appropriate behavior. This then forces manufacturers, traders, retailers, and others down the line to adjust in order to avoid losing money. For example, they could charge more for other products or services, they could buy lower-quality raw materials, or they could lay off workers. Friedman demonstrates that these outcomes are rarely good, and often lead to a cascading effect which impacts the economy in far-reaching and unpredictable ways. It would be better to ride out whatever temporary pain price fluctuations may cause while allowing the market to adjust itself.

Friedman’s chapters on tariffs and price controls (“A Tyranny of Controls”), and social security and welfare (“From Cradle to Grave”) best demonstrate the folly of high-mined government interference. Often, the results reflect the opposite of the intended result:

The objectives have all been noble; the results, disappointing. Social Security expenditures have skyrocketed, and the system is in deep financial trouble. Public housing and urban renewal programs have subtracted from rather than added to the housing available to the poor. Public assistance rolls mount despite growing employment. By general agreement, the welfare program is a “mess” saturated with fraud and corruption. As government has paid a larger share of the nation’s medical bills, both patients and physicians complain of rocketing costs and of the increasing impersonality of medicine. In education, student performance has dropped as federal intervention as expanded.

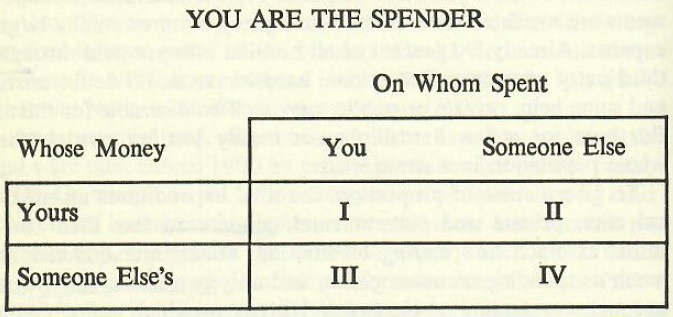

Friedman also offers an elegant Punnett Square to visualize what happens when people spend money and on whom.

Obviously, money spent in categories I and II is our money, and will more likely meet a higher bar of responsibility and thrift than money spent in categories III and IV. Friedman does a wonderful job explaining what happens in these latter two categories:

The bureaucrats spend someone else’s money on someone else. Only human kindness, not the much stronger and more dependable spur of self-interest, assures that they will spend the money in the way most beneficial to the recipients. Hence the wastefulness and ineffectiveness of the spending.

So, bad things happen when government fails to respect economic interconnectivity and the objective value of prices. This notion may oversimplify Free to Choose, but it certainly constitutes the thematic basis of nearly all its chapters. Countries will avoid this trap and achieve economic prosperity as long as they allow for two things: personal liberty for their citizens and limited government.

That’s the takeaway from Free to Choose. Again, it’s not wrong, but it works best as a policy rubric for a government whose primary interest is the prosperity of its people as opposed to, say, tribalism, ideological aims, or sheer profiteering. For example, Friedman believe that Western nations began playing with fire once they abandoned the gold standard:

Until fairly recently the power of the Federal Reserve Banks to create currency and deposits was limited by the amount of gold held by the System. That limit has now been removed so that today there is no effective limit except the discretion of the people in charge of the System.

The government can print money, and the Fed can manipulate interest rates, but this only increases overall deposits in banks; it does not increase the objective value of money. Thus, we have that dreaded word from the 1970s: inflation. Friedman’s best chapter is perhaps “The Cure for Inflation,” in which he convincingly posits the causal relationship between money supply and inflation: the greater the supply, the greater the inflation. He concedes that reducing the money supply to cure inflation can increase unemployment. But this, he argues, is merely an unfortunate and temporary side effect of curing inflation. Free to Choose is largely bereft of hard data with its meager footnote section and lack of a bibliography (at least in my 1990 edition), but this chapter contains several graphs demonstrating this relationship in places as diverse as the United States, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Japan.

Friedman unfortunately takes his economic philosophy too far in many places. Some of his predictive concerns have not aged well (such as his pessimism regarding the Food and Drug Administration’s regulation of pharmaceutical drug testing). He does not anticipate how wealth and prosperity can lead to what I would call post-economic concerns. And his complete avoidance of racial realities prevent Free to Choose from being the fount of wisdom it purports to be. The book has three main blind spots.

The chapter entitled “What’s Wrong With Our Schools?” misses the mark so broadly that it really should not have been included at all. It’s one thing to point out the corruption, ideological conformity, and waste associated with the Department of Education (as with any other federal institution). It’s something else entirely to consider education as another kind of market subject to pressure from supply and demand, equivalent to manufacturing and selling pens and pencils. For Friedman, the customer pays the government for its public education services, but does not get his money’s worth due to either shoddy service, poor results, or both. While he does recognize that this problem exists chiefly among America’s black population, he neglects to mention the fact that white Americans didn’t have as many issues with public education before integrating with blacks — and still don’t, as long as there are few to no blacks in their schools. For Friedman, public education does not even rise to the status of a necessary evil. It’s just evil, like social security. And he uses the plight of black Americans to prove it.

You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s young adult novel The No College Club here.

This, of course, will be unconvincing to the race realist who knows that black difficulties with any formal education stem mostly from IQ and temperament deficiencies, not from the fact that public schools are state-sanctioned monopolies protected from free-market competition. Friedman tries to get around this with his far-fetched voucher scheme. Basically, since government spends a certain amount of a citizen’s tax dollars educating his child, that citizen should have the right to forego this service for a refund in the form of vouchers. These could then be redeemed as tuition at whatever government-approved school the citizen wishes to send his child to. (The citizen is free to choose any school the government allows him to choose, you see.)

This might improve the plight of that small percentage of inner-city black families whose children are bright enough to get something out of academic instruction. Indeed, the scanty evidence Friedman provides (e.g., St. Chrysostom’s Parochial School in the Bronx, in New York City) involves only those inner-city blacks who were willing to pay to educate their children in the first place. This hardly represents the middle of the black bell curve. Friedman then asserts without evidence that his voucher plan would “moderate racial conflict and promote a society in which blacks and whites cooperate in joint objectives, while respecting each other’s separate rights and interests.” This is an utterly absurd claim.

For most blacks, Friedman’s voucher plan would merely shuffle the problem around without solving it: The kids would perform poorly no matter what school they attended. Yes, Friedman does call for an end to compulsory education, but this would cause the pathologies plaguing black schools to burden law enforcement a few years earlier. Further, he routinely and naïvely refers to black “parents” in the plural, as if black illegitimacy were as low as white illegitimacy. Then, hilariously, he characterizes the accurate assessment that many blacks “have little interest in their children’s education and no competence to choose for them” as a “gratuitous insult.” This argues against the facts since, time and time again, inner-city blacks will either vote for leaders who do little or nothing to improve their schools or vote with their feet and move to the suburbs to be among whites.

Friedman himself admits that he doesn’t understand why blacks — whom he claims care so much about educating their children — reject his voucher plan. He feels the same way about black support for the minimum wage, which he deems “one of the most, if not the most, antiblack laws on the statute books.” Why would blacks consistently act against their individual interests? He suggests that they are in thrall to their own political leaders, who “see control over schooling as a source of political patronage and power.” He’s half-correct in this. He is, however, missing the fact that black Americans as a collective diaspora benefit from poor schools, poor neighborhoods, and high crime rates in the inner cities, because these blemishes keep non-blacks out of areas which blacks have claimed for themselves. This preserves the diaspora from assimilation into the broader population almost in an ecological sense, and also lends blacks as a group a measure of prestige on the national stage. If there are black territories, then there will be black Congressmen. Good schools, among other positive outcomes from Friedman’s platform, threaten this. See my essay “If I Were Black I’d Vote Democrat” for more on this idea.

And here we get to the first major blind spot of Free to Choose, and of libertarianism in general. Smith’s “uniform, constant, and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition” applies best in monoracial societies, such as those that Adam Smith would have experienced back in the eighteenth century. In multiracial societies, however, a person’s natural ethnocentrism will more often compel him to act in the best interest of his group vis-à-vis other groups, even at his own personal expense. Adam Smith’s classical economics, as seen through the lens of Free to Choose, simply does not account for this. Instead, Friedman expects that blacks should be happy with the modest gains his platform offers them as individuals, while ignoring what they really want as a racial group: equality and power. Because the genetic link to intelligence and racial differences in psychometric testing had been well-established by the time of this book’s writing, there is no forgiving this oversight. It can only stem from ignorance, cowardice, or cynicism.

Friedman’s second blind spot, however, is more forgivable. Often in Free to Choose he frets over the dangers of tyranny, as would be expected. This is all well and good. But never does he look at the downside of oligarchy. Yes, he finds monopoly reprehensible, but only because it harms economies by interfering with the natural function of prices. The ideological oligarchs we have today — for example, the people giving away fortunes to Left-wing causes, facilitating untrammeled non-white immigration into Europe, and financing dysgenic phenomena such as transgenderism — cannot be explained easily in Free to Choose, and will likely do more damage than fat cats playing Monopoly in their top hats and monocles.

These oligarchs are so wealthy that they simply care less about market forces than do mere millionaires who, relative to them, still have to fight and scrape to survive. This is a post-economic condition in which a person no longer needs to “better his condition,” because his condition simply cannot get any better. Hence we have Gillette alienating its prime customers in an advertisement decrying toxic masculinity. Hence we have Target uglifying its stores with images of overweight models. Hence we have Disney catering to the Left-wing fringe in empty theaters. Yes, if you go woke, you go broke. But if you have post-economic oligarchs paying you to go woke, then you don’t go broke. You might even make money.

Again, this is something not anticipated by either Smith or Friedman.

The final blind spot of Free to Choose became evident to me after reading this paragraph:

Financing government spending by increasing the quantity of money is often extremely attractive to both the President and members of Congress. It enables them to increase government spending, providing goodies for their constituents, without having to vote for taxes to pay for them, and without having to borrow from the public.

In a free society, exactly how is this scenario not inevitable?

The onus is on any of Milton Friedman’s supporters to answer this simple question. Universal suffrage eventually produces leaders who reflect the values and intelligence of their constituents. A black woman with an IQ of 89, living in an inner-city apartment while raising four illegitimate children will vote for the candidate promising rent control, because rent control is tangible and easily understood. She will have no time for fancy thought experiments about how artificially lowering rent interferes with the incentivizing function of prices. And she will continue to vote for candidates who support rent control, even though their ham-fisted policies never seem to bear fruit. With enough voters such as this woman, we end up with politicians who would rather ignore the objective value of money and instead print more of it whenever it suits them, thereby guaranteeing inflation.

In essence, Free to Choose is blind as to how its policies will always be thwarted by the very freedom its author strenuously promotes: universal suffrage. If Friedman had been serious about implementing his ideas, he would have also pushed to abolish universal suffrage and replace it with a more limited, merit-based democracy. This would ensure that a greater percentage of the enfranchised public has the mental capacity to understand economic interconnectivity, the objective value of prices, and all the other terrific stuff you can pay $15.99 to read about in Free to Choose. Friedman himself laments the fact that “[t]o the despair of every economist, it seems almost impossible for most people other than trained economists to comprehend how a price system works.” If so, then why do we depend upon the general public to ultimately determine how price systems work? Until we get a satisfying answer, we can only conclude that Free to Choose amounts to little more than an elaborate and intellectually stimulating grift.

I don’t wish to end this review with condemnation. Libertarianism became a gateway drug for the dissident Right for good reasons. There is quite a bit of overlap, largely because libertarian policies were originally envisioned within the context of white norms, the same white norms which dissidents strive to recapture today. Friedman is as good a mouthpiece as any for this. He promotes many undeniable virtues, such as monogamous families, self-reliance, and financial discipline. His conception of human nature in many places is realistic. He abhors tyranny and oppression. He also urges that we accept inequality as a fact of life. Not coincidentally, his biggest opponents — whom he lists in Free to Choose as the universities, the news media, and government bureaucracy — have become some of the greatest enemies of today’s dissident Right. The people who resisted Friedman’s calls for lower taxes and free trade in 1980 are today doing the bidding of anti-white hate groups such as the Anti-Defamation League and are cheering on the Great Replacement.

It would be better to view libertarianism as a farm league for White Nationalism rather than a regrettable and embarrassing phase in many of our pasts. The problem is one of scale. Friedman sells his idea by promising smaller proportions of a bigger pie, which leads to greater wealth in absolute terms. But he forgets that power is a zero-sum game. If I get more of the pie, you must get less of it. This is what makes the world go round, and if one wishes to gain any of kind of real power, he’d be better served reading Machiavelli than Milton Friedman. Yes, Friedman offers excellent economic advice, but he does not delve deep enough into human nature to develop a comprehensive political philosophy.

Imagine a chemist trying to solve a problem in physics, and you have Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Related

-

Whither Thou Goest, Diaspora?

-

Get to Know Your Friendly Neighborhood Habsburg

-

Thank You, O. J. Simpson

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

19 comments

Libertarianism is more an antipolitical than a political ideology, which probably explains why so many Jews seem to be instinctually drawn to libertarianism. Perhaps they subconsciously hope to defuse white ethnocentrism by channeling western whites fed up with the system into a radically individualist ethical framework that reinforces the status-quo by portraying all collective and political action as morally reprehensible. This article opened my eyes to a new layer of sinister Jewish cynicism, seeing how libertarians like Friedman scapegoat the problems of diversity by claiming that all public goods, like education and social security, are simply evil. He misdirects from the problem and simultaneously intensifies the spiritual miasma of anti-social individualism that is suffocating the West.

Is it possible that Friedman was just applying the Sam Francis method of conveying ideas when they’re applicable to blacks. “There’s only so much I can say and still be mainstream “? Sam applied that to Jews as well. There’s quite a few people here that forget his wisdom.

I would tend to doubt that. Sam Francis was one of us. He did indeed push the limit as far as he could get away with, and got burnt by the MSM a couple of times by crossing the line.

Friedman, on the other hand, seems pretty sincere about his absolute egalitarianism. It’s a common problem with many Libertarians, leading to flaws in their ideology. Unfortunately, Ayn Rand took it a little further. Failing to reject this leftist core premise will be a disadvantage.

Libertarians have an unsurpassed understanding of the praxeological, but little understanding of the political (or, really, of the human condition as such). Libertarian ideology is also often the enemy of really existing liberty (an extreme example: advocating open borders for parasites who will vote for socialists to transfer their wealth, or even for terrorists who will enter and kill them). And anyway, we’re not libertarians; we’re white preservationists and nationalists. I treasure liberty (and I understand ‘liberty’ exactly as libertarians do) and capitalist prosperity, but I place a still higher value on white perpetuity and Occidental continuity. Indeed, I don’t think that liberty can even survive apart from white majority societies – an anthropological, not philosophical or praxeological, claim.

But this was a well written review of a book I chanced upon (with exhilaration, I recall, having a) earlier read Capitalism and Freedom; b) by then long been a reader of my dad’s and later my schools’ copies of Newsweek, with its regular Milton Friedman column back in the 70s and early 80s; and c) seen some of the Free To Choose video lectures – the original basis for the later book – with my parents ) in my college library more than 40 years ago.

I would note for the sake of accuracy that Friedman’s discussion of how the free market coordinates the production of a pencil (the point was that no single person could actually make himself, from start to finished product, a simple mid-20th century pencil; it requires a very dense division of labor across multiple specialties) had been based on an essay from Leonard Read, the founder of the still-existent classical liberal Foundation for Economic Education, published over two decades earlier:

https://fee.org/articles/i-pencil/

Friedman does credit Read for the I, Pencil idea.

Fantastic essay Mr. Quinn. 30 years ago or so, MF was one of my main intellectual heroes. I remember thinking that we just need another MF, another Ronald Reagan and another William F. Buckley and that this would fix everything. I no longer think that, of course. Have you read Murray Rothbard’s “Milton Friedman Unraveled”? This essay shows many of MFs fallacies.

No, I have not read that Rothbard essay but will check it out. Thanks!

I am a white nationalist and I have always hated libertarianism with passion. Moreover, if people of white European stock and their culture are to survive American made corporate capitalism has to die. I much prefer a national absolute monarchy as a natural habitat for cultured Whites.

You were in tune with your survival instinct a lot sooner than I was.

That’s odd. The proper stance towards libertarianism for any white American ought to be one of reluctant, regretful disavowal. America is preeminently the Republic of Liberty. That is what most distinguishes us from our European, and even British, kinsmen. A large part of America’s massive historical success, especially its amazingly rapid settlement and industrialization, can be traced to the ideals and reality of liberty under law; Constitutionally ultra-limited government, especially at the Federal level; once inviolable, and later at least comparatively strong, private property rights; and the free market economy – all tenets the defense of which constitutes the larger portion and purpose of libertarianism. Unlike the alien and repellent creed of socialism, libertarianism is perfectly congruent with American history and public mythology.

That does not make libertarianism ideal, however. As far back as the 80s, when I was actively studying ideologies of the (center-)Right in grad school, I already recognized the fundamental flaws of libertarianism: namely and among others, that it relies upon a strong grounding in a moral system (specifically, Christianity) prior to and standing apart from libertarianism itself; and that its radical ethical individualism is anthropologically (and geostrategically) naive. Libertarianism works wonderfully well when it can ‘parasite’ off of a foundational Christian culture, and when it operates within ethnically (or at least racially) homogeneous parameters. The more ‘diverse’ a society, as well as the less Christian, the less effective libertarianism is at meeting the stresses and challenges routinely faced by any society.

So I recognize that libertarianism is simply inadequate to saving my country and what I treasure about it. But I feel lingering affection for an ideology that, as long as it is racially bounded (as it would be in a foundationally and rigorously maintained apartheid ethnostate), is reasonably in accord with human nature, and which highly resonates with my sense of justice rooted in respect for individual rights.

A free country is a noble goal. But in a free country (pace libertarian doctrine) you need three basic things:

Defense against foreign invaders; and

Law enforcement to prevent fraud and illegal force; and

Courts which arbitrate disputes according to rational laws.

None of these three “basics” exist under the current Regime. Do we need elaborate on the situation with open borders/mass migrations/globalization? Or the stand-down orders and defunding of the police? Or the corruption of the justice system via lawfare and political weaponization?

The dilemma is that libertarianism in the modern sense (i.e., Friedman, et alia) emerged at a time when America was still a 90% White country (mid-20th century) and White values were the norm. You also had a capitalist sector which, in the main, was nationalistic insofar as there was American industry, while globalization had yet to become the dominant force. One could talk of economic freedom and personal freedom being interlinked. But in an era of IT corporations canceling dissidents, and Wall Street pushing ESG against market realities – that consensus has long since been wrecked.

One reason that libertarianism has become a gateway for many people to enlist with the Dissident Right is that it provides a certain rational (if unstated) framework whose conclusions come down to the case for nationalism. i.e., if you want to have the “basics” of a free society then you need a common people who hold a common consensus on the political order.

Today, the Dissident Right is creating the new consensus. Nation first, then we can be “free to choose.”

During the American economic turmoil beginning in the early 1970s, I sensed in the words of the Bard that there was defininitely something rotten in the state of Denmark.

So barely past my first decade of life, I started reading a lot of mildly-dissident literature on political and economic issues, e.g., Gary North and many others. I was taught here that the problem was Keynesian economics or the Central Banks, and that Libertarianism and deregulation somehow had all the answers.

This led me to read more about Monetarism and the (((Austrian School))) of economics and our friend (((Milton Friedman))).

Funny story ─ I was half way through Free to Choose over forty years ago while in Signal School at Fort Gordon, GA in the U.S. Army. We had a snap locker inspection one day and the dope-sniffing dogs were brought through by the Military Police. No contraband found.

As I recall, we were allowed to have one book or magazine in our ship-shape lockers. While most everybody else had the latest pornographic books stuffed in there, I was studying Uncle Milty. And this got a lot of chuckles from the senior sergeants.

I wanted to believe ─- but I was not fully convinced.

George Lincoln Rockwell wrote in the early 1960s that Conservatism is a plan for failure because Conservatives were limited to “conserving what is already gone.” Sage advice.

In the end, I rejected Milton Friedman as toxic Conservativism of the richest kind ─ particularly his notion of Free Trade.

Red China had just been opened up as a full trading partner and we were all supposed to get rich selling widgets to “a billion consumers.” Instead we got what Texas oilman Ross Perot called a “giant sucking sound” of American jobs moving overseas, and cheap Asian crap flooding our markets.

During the Reagan years we were young Baby Boomers and thought we had the tiger by the tail. But that reality was the receiving end of the tiger’s irritated bowels.

Free Trade means an international specialization of labor, which means that we produce McDonalds hamburgers and sell dodgy life insurance policies, while somebody else makes precision Swiss watches and quality manufactured goods that last longer than the next business quarter ─ or at least somebody produces quality machinery until the disposable Chinese junk floods the market and the plants relocate to Mexico in search of cheaper labor and substandard benefits.

Try going to the hardware store and buying an electric generator that lasts longer than the next hurricane season if you don’t believe me.

So, with due respect to this fine article, I am going to say that far from being nostalgic about Uncle Milty and selling a pretty picture profusely plumed with our free-dumbs, this mind-of-the-market nonsense is simply toxic waste.

Libertarianism is a good way to sterilize the prize bull before the first gate flies open at the rodeo. It is almost easy to believe that it was planned that way from the beginning.

Furthemrore, billion-dollar multinational corporations do not fuss much about “central planning.” Markets to a big extent are what they say they are.

They plan from the grassroots if it suits them, and they plan from the top-down when it suits them. They shamelessly promote their private interests in and at the expense of the public sphere with the gravitas and finesse of a Black Hole innocently traversing the solar system.

They promote degeneracy of all kinds and race-mixing. I have to curb my inclination here to Fed-Post. But this is the opposite of organic, folkish Nationalism as I think of it.

And even if these Plutocrats do not actively collude with fellow internationalist business cabals, only the largest governments ever have any power or hope whatsoever to counter this beastly calculus.

We have to seize power and punish traitors. Running to the hills will not save us.

🙂

Libertarians like to credit ‘capitalism’ and ‘free markets’ for outcomes (like pencil production) that depended upon phenomena that have nothing to do with ‘capitalism’ but are, instead, the result of White ingenuity and White co-operative behavior.

Libertarianism – like Christianity and Liberalism and so many anti-White ideological constructs – are entirely dependent on White. There are no universal values and there is no ‘sound money’ without Whites. As a jew, Friedman knew that his policies promoted rule by ethnic bankers like himself.

Libertarianism is propaganda for the ethnic bankers, nothing more. Wherever ‘free market’ ideology has been tried it resulted disaster.

Adam’s Smith ‘invisible hand’ is magical thinking at its most surreal.

Why am I not a libertarian? I respect personal freedom and free speech, but the free market destroys – freedom, free speech and nice white lands. The free market leads to oligopoly and domination by woke corporations. And libertarians are incapable of thinking about that and adjust their ideology. Libertarianism doesn’t address ecology, non-white immigration, Jewish evolutionary strategy, and libertarianism leads to white atomisation.

Here is a useful meme from Jewish Contributions about their role in promoting libertarianism.

https://t.me/JewishContributions/263

I remember how libertarianism was in vogue in the 1990s. It was mainly espoused by evil arrogant querulous antisocial people (Ayn Rand was an example of such a person). It was an ideology to represent selfish brutality as a virtue. Certain White nationalists were lured into libertarianism out of spite against non-whites. But for many reasons libertarian policies harm Whites more. It is not only the poor Whites who suffer but the middle classes as well. Among other things it creates an atmosphere of distrust and individualism that prevents Whites from having families. It makes white countries less livable. It destroys natural environment and cultural heritage. It brings the worst people to the top of society. Often times when libertarians speak of “tyranny” they mean justice and order.

I seem to remember there was a speech Greg Johnson did about libertarianism. Possibly an old London Forum video? But I can’t seem to find it.

Anyway, we definitely need to create content that lures libertarians towards us so we can move people through that pipeline faster.

100% agree

You ain’t gonna do so with a bunch of socialist crap, including national socialist / Right-laborist crap. The ethical sentiments, praxeological theory, and sociological (but note: not anthropological) realism undergirding libertarianism are too intellectually powerful.

I’ve made maybe five converts over the decades from libertarianism to either race-realistic libertarianism, or outright white nationalism. Race-realism is a much easier sell, as many (most?) libertarians are highly analytical white males, and the facts of racial differences, once presented, speak for themselves. Even persuading libertarians of the need for white advocacy is relatively easy as the reality of antiwhite double standards and mistreatment within our factional society and special-pleader governing system is plain for all except the willfully blind (amongst whom are, unfortunately, a not insignificant number of stubborn radical individualists who are obviously under the influence of a deep psychological animus towards any type of “collectivism”, even if it’s merely a defensive reaction to the aggressive racial collectivism of others).

Getting the libertarian over to white nationalism is a much tougher task, but hardly impossible. The key is to emphasize for starters that, first, now and in the past, only whites seem to embrace either radical individual rights or libertarianism in large numbers; second, the kind of society that libertarianism seeks has only ever been approximated among either whites, or, in the case of formerly radically free Hong Kong, a nonwhite people whose laissez-fairist politico-economic structure was set up by whites; third, limited government regimes are built upon a foundation of high social trust, and that diversity, especially racial, is inimical to social trust, and this for ineradicable (genetic similarity) reasons; fourth, apart from its biologically negative aspects, diversity has been weaponized by, and is thus an ally of, the socialist-totalitarian Left; and fifth, only in re-whitened nations will (white) libertarians have a chance at restoring radically minimally statist polities, and the best and probably only way to re-whiten nations is via a long prior period of white nationalist activism and politics.

These are not sophists’ arguments, either (ie, ones formulated to seduce libertarians to join our side). I do believe that our own Constitutionally limited republic will only have any chance at being restored within a future white American ethnostate.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment