Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled3,251 words

Libertarianism can elicit strong reactions from dissidents these days, largely because it has been such a common gateway drug for the Right. Many white identitarians today came of age as libertarians, and so have intimate knowledge not only of that marvelously balanced and consistent belief system, but of all the reasons why they ultimately abandoned it. Libertarianism, despite its virtues, has nevertheless proven inadequate as a political ideology, and is therefore a recipe for defeat for those who wish to stem or reverse the rising tide of the Left. This does not mean, however, that libertarianism should be abandoned completely. Its precepts should never leave the economic arsenal of any modern civilization that wishes to prosper. People should not blind themselves to this and fall for the specious notion that because libertarianism cannot take us to the Promised Land, it can therefore take us nowhere.

Free to Choose, the 1980 “Personal Statement” by Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman and his wife Rose, offers an excellent beginner course on libertarianism, complete with examples, thought experiments, and theoretical underpinnings. As far as literature-as-persuasion goes, it’s first rate; at times brilliant. Friedman has a philosopher’s mind as he manipulates different ideas within a unified logical framework. But just as libertarianism fails to incorporate certain crucial aspects of the human condition, so does Free to Choose. Human beings are so much more than mere economic actors, and no, political systems should not be treated as markets.

From the beginning, Friedman adheres to the tenets found in Adam Smith’s 1776 treatise The Wealth of Nations. Friedman provides an adequate rundown of the basics of economics and deftly argues how crucial individualism and liberty are for successful societies. Economic freedom, for Friedman, is a prerequisite for political freedom — and he’s not wrong. Libertarianism relies on using the “uniform, constant, and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition,” in the words of Smith, as the engine for economic growth and prosperity. This is a natural — and therefore superior — alternative to top-down, centralized efforts to control economies in the name of some ideal, usually egalitarianism of some sort.

In his Introduction, Friedman expresses his goal in Free to Choose thusly; note its modesty:

We have the opportunity to nudge the change in opinion toward greater reliance on individual initiative and voluntary cooperation, rather than toward the other extreme of total collectivism.

[2]

[2]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s Solzhenitsyn and the Right here [3].

Because Free to Choose presents libertarianism as a complete political ideology, however, it revisualizes human nature almost at the cellular level. Friedman proposes a radical departure from the paternalistic socialism prevalent among twentieth-century Western thinkers to less mainstream, yet principled individualism — a leap that many have found to be a bridge too far. But Friedman’s admission is quite telling. When viewed as a mere suggestion for people who are already in power, Free to Choose retains great value; when viewed as a political philosophy for people who wish to gain power, not so much.

Using the idea of a pencil’s life cycle, Friedman illustrates two of his primary ideas in Free to Choose: interconnectivity and the functions of prices. This common utensil made of wood, metal, graphite, and factice (the material used for erasers) depends on an astonishing confluence of raw materials, manufacturing, transportation, and marketing — all of which are determined by prices. A shortage of a certain raw material, a railway strike in a certain area, severe weather conditions, or an innovation in a competing utensil such as pens could impact the balance of supply and demand and drive the price of pencils higher or lower for a time. Friedman’s point is that prices tell us something about the interrelatedness of the myriad of happenstances that go into making any number of items that you and I can find almost anywhere. When government artificially controls prices in reaction to, say, geopolitical events or to curry favor with constituents, such as through tariffs or price freezes, they are interfering with prices’ ability to convey accurate information and incentivize appropriate behavior. This then forces manufacturers, traders, retailers, and others down the line to adjust in order to avoid losing money. For example, they could charge more for other products or services, they could buy lower-quality raw materials, or they could lay off workers. Friedman demonstrates that these outcomes are rarely good, and often lead to a cascading effect which impacts the economy in far-reaching and unpredictable ways. It would be better to ride out whatever temporary pain price fluctuations may cause while allowing the market to adjust itself.

Friedman’s chapters on tariffs and price controls (“A Tyranny of Controls”), and social security and welfare (“From Cradle to Grave”) best demonstrate the folly of high-mined government interference. Often, the results reflect the opposite of the intended result:

The objectives have all been noble; the results, disappointing. Social Security expenditures have skyrocketed, and the system is in deep financial trouble. Public housing and urban renewal programs have subtracted from rather than added to the housing available to the poor. Public assistance rolls mount despite growing employment. By general agreement, the welfare program is a “mess” saturated with fraud and corruption. As government has paid a larger share of the nation’s medical bills, both patients and physicians complain of rocketing costs and of the increasing impersonality of medicine. In education, student performance has dropped as federal intervention as expanded.

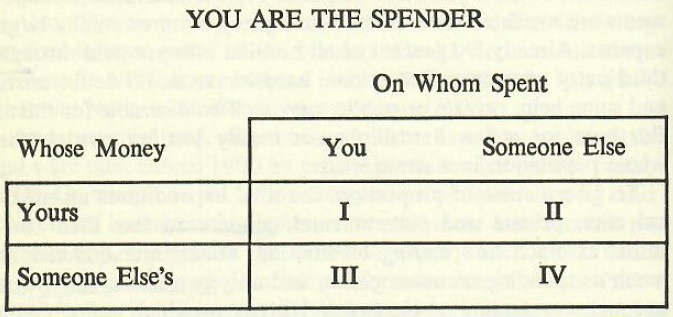

Friedman also offers an elegant Punnett Square to visualize what happens when people spend money and on whom.

Obviously, money spent in categories I and II is our money, and will more likely meet a higher bar of responsibility and thrift than money spent in categories III and IV. Friedman does a wonderful job explaining what happens in these latter two categories:

The bureaucrats spend someone else’s money on someone else. Only human kindness, not the much stronger and more dependable spur of self-interest, assures that they will spend the money in the way most beneficial to the recipients. Hence the wastefulness and ineffectiveness of the spending.

So, bad things happen when government fails to respect economic interconnectivity and the objective value of prices. This notion may oversimplify Free to Choose, but it certainly constitutes the thematic basis of nearly all its chapters. Countries will avoid this trap and achieve economic prosperity as long as they allow for two things: personal liberty for their citizens and limited government.

That’s the takeaway from Free to Choose. Again, it’s not wrong, but it works best as a policy rubric for a government whose primary interest is the prosperity of its people as opposed to, say, tribalism, ideological aims, or sheer profiteering. For example, Friedman believe that Western nations began playing with fire once they abandoned the gold standard:

Until fairly recently the power of the Federal Reserve Banks to create currency and deposits was limited by the amount of gold held by the System. That limit has now been removed so that today there is no effective limit except the discretion of the people in charge of the System.

The government can print money, and the Fed can manipulate interest rates, but this only increases overall deposits in banks; it does not increase the objective value of money. Thus, we have that dreaded word from the 1970s: inflation. Friedman’s best chapter is perhaps “The Cure for Inflation,” in which he convincingly posits the causal relationship between money supply and inflation: the greater the supply, the greater the inflation. He concedes that reducing the money supply to cure inflation can increase unemployment. But this, he argues, is merely an unfortunate and temporary side effect of curing inflation. Free to Choose is largely bereft of hard data with its meager footnote section and lack of a bibliography (at least in my 1990 edition), but this chapter contains several graphs demonstrating this relationship in places as diverse as the United States, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Japan.

Friedman unfortunately takes his economic philosophy too far in many places. Some of his predictive concerns have not aged well (such as his pessimism regarding the Food and Drug Administration’s regulation of pharmaceutical drug testing). He does not anticipate how wealth and prosperity can lead to what I would call post-economic concerns. And his complete avoidance of racial realities prevent Free to Choose from being the fount of wisdom it purports to be. The book has three main blind spots.

The chapter entitled “What’s Wrong With Our Schools?” misses the mark so broadly that it really should not have been included at all. It’s one thing to point out the corruption, ideological conformity, and waste associated with the Department of Education (as with any other federal institution). It’s something else entirely to consider education as another kind of market subject to pressure from supply and demand, equivalent to manufacturing and selling pens and pencils. For Friedman, the customer pays the government for its public education services, but does not get his money’s worth due to either shoddy service, poor results, or both. While he does recognize that this problem exists chiefly among America’s black population, he neglects to mention the fact that white Americans didn’t have as many issues with public education before integrating with blacks — and still don’t, as long as there are few to no blacks in their schools. For Friedman, public education does not even rise to the status of a necessary evil. It’s just evil, like social security. And he uses the plight of black Americans to prove it.

[5]

[5]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s young adult novel The No College Club here [6].

This, of course, will be unconvincing to the race realist who knows that black difficulties with any formal education stem mostly from IQ and temperament deficiencies, not from the fact that public schools are state-sanctioned monopolies protected from free-market competition. Friedman tries to get around this with his far-fetched voucher scheme. Basically, since government spends a certain amount of a citizen’s tax dollars educating his child, that citizen should have the right to forego this service for a refund in the form of vouchers. These could then be redeemed as tuition at whatever government-approved school the citizen wishes to send his child to. (The citizen is free to choose any school the government allows him to choose, you see.)

This might improve the plight of that small percentage of inner-city black families whose children are bright enough to get something out of academic instruction. Indeed, the scanty evidence Friedman provides (e.g., St. Chrysostom’s Parochial School in the Bronx, in New York City) involves only those inner-city blacks who were willing to pay to educate their children in the first place. This hardly represents the middle of the black bell curve. Friedman then asserts without evidence that his voucher plan would “moderate racial conflict and promote a society in which blacks and whites cooperate in joint objectives, while respecting each other’s separate rights and interests.” This is an utterly absurd claim.

For most blacks, Friedman’s voucher plan would merely shuffle the problem around without solving it: The kids would perform poorly no matter what school they attended. Yes, Friedman does call for an end to compulsory education, but this would cause the pathologies plaguing black schools to burden law enforcement a few years earlier. Further, he routinely and naïvely refers to black “parents” in the plural, as if black illegitimacy were as low as white illegitimacy. Then, hilariously, he characterizes the accurate assessment that many blacks “have little interest in their children’s education and no competence to choose for them” as a “gratuitous insult.” This argues against the facts since, time and time again, inner-city blacks will either vote for leaders who do little or nothing to improve their schools or vote with their feet and move to the suburbs to be among whites.

Friedman himself admits that he doesn’t understand why blacks — whom he claims care so much about educating their children — reject his voucher plan. He feels the same way about black support for the minimum wage, which he deems “one of the most, if not the most, antiblack laws on the statute books.” Why would blacks consistently act against their individual interests? He suggests that they are in thrall to their own political leaders, who “see control over schooling as a source of political patronage and power.” He’s half-correct in this. He is, however, missing the fact that black Americans as a collective diaspora benefit from poor schools, poor neighborhoods, and high crime rates in the inner cities, because these blemishes keep non-blacks out of areas which blacks have claimed for themselves. This preserves the diaspora from assimilation into the broader population almost in an ecological sense, and also lends blacks as a group a measure of prestige on the national stage. If there are black territories, then there will be black Congressmen. Good schools, among other positive outcomes from Friedman’s platform, threaten this. See my essay “If I Were Black I’d Vote Democrat” [7] for more on this idea.

And here we get to the first major blind spot of Free to Choose, and of libertarianism in general. Smith’s “uniform, constant, and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition” applies best in monoracial societies, such as those that Adam Smith would have experienced back in the eighteenth century. In multiracial societies, however, a person’s natural ethnocentrism will more often compel him to act in the best interest of his group vis-à-vis other groups, even at his own personal expense. Adam Smith’s classical economics, as seen through the lens of Free to Choose, simply does not account for this. Instead, Friedman expects that blacks should be happy with the modest gains his platform offers them as individuals, while ignoring what they really want as a racial group: equality and power. Because the genetic link to intelligence and racial differences in psychometric testing had been well-established by the time of this book’s writing, there is no forgiving this oversight. It can only stem from ignorance, cowardice, or cynicism.

Friedman’s second blind spot, however, is more forgivable. Often in Free to Choose he frets over the dangers of tyranny, as would be expected. This is all well and good. But never does he look at the downside of oligarchy. Yes, he finds monopoly reprehensible, but only because it harms economies by interfering with the natural function of prices. The ideological oligarchs we have today — for example, the people giving away fortunes to Left-wing causes, facilitating untrammeled non-white immigration into Europe, and financing dysgenic phenomena such as transgenderism — cannot be explained easily in Free to Choose, and will likely do more damage than fat cats playing Monopoly in their top hats and monocles.

These oligarchs are so wealthy that they simply care less about market forces than do mere millionaires who, relative to them, still have to fight and scrape to survive. This is a post-economic condition in which a person no longer needs to “better his condition,” because his condition simply cannot get any better. Hence we have Gillette alienating its prime customers in an advertisement decrying toxic masculinity. Hence we have Target uglifying its stores with images of overweight models. Hence we have Disney catering to the Left-wing fringe in empty theaters. Yes, if you go woke, you go broke. But if you have post-economic oligarchs paying you to go woke, then you don’t go broke. You might even make money.

Again, this is something not anticipated by either Smith or Friedman.

The final blind spot of Free to Choose became evident to me after reading this paragraph:

Financing government spending by increasing the quantity of money is often extremely attractive to both the President and members of Congress. It enables them to increase government spending, providing goodies for their constituents, without having to vote for taxes to pay for them, and without having to borrow from the public.

In a free society, exactly how is this scenario not inevitable?

The onus is on any of Milton Friedman’s supporters to answer this simple question. Universal suffrage eventually produces leaders who reflect the values and intelligence of their constituents. A black woman with an IQ of 89, living in an inner-city apartment while raising four illegitimate children will vote for the candidate promising rent control, because rent control is tangible and easily understood. She will have no time for fancy thought experiments about how artificially lowering rent interferes with the incentivizing function of prices. And she will continue to vote for candidates who support rent control, even though their ham-fisted policies never seem to bear fruit. With enough voters such as this woman, we end up with politicians who would rather ignore the objective value of money and instead print more of it whenever it suits them, thereby guaranteeing inflation.

In essence, Free to Choose is blind as to how its policies will always be thwarted by the very freedom its author strenuously promotes: universal suffrage. If Friedman had been serious about implementing his ideas, he would have also pushed to abolish universal suffrage and replace it with a more limited, merit-based democracy. This would ensure that a greater percentage of the enfranchised public has the mental capacity to understand economic interconnectivity, the objective value of prices, and all the other terrific stuff you can pay $15.99 to read about in Free to Choose. Friedman himself laments the fact that “[t]o the despair of every economist, it seems almost impossible for most people other than trained economists to comprehend how a price system works.” If so, then why do we depend upon the general public to ultimately determine how price systems work? Until we get a satisfying answer, we can only conclude that Free to Choose amounts to little more than an elaborate and intellectually stimulating grift.

I don’t wish to end this review with condemnation. Libertarianism became a gateway drug for the dissident Right for good reasons. There is quite a bit of overlap, largely because libertarian policies were originally envisioned within the context of white norms, the same white norms which dissidents strive to recapture today. Friedman is as good a mouthpiece as any for this. He promotes many undeniable virtues, such as monogamous families, self-reliance, and financial discipline. His conception of human nature in many places is realistic. He abhors tyranny and oppression. He also urges that we accept inequality as a fact of life. Not coincidentally, his biggest opponents — whom he lists in Free to Choose as the universities, the news media, and government bureaucracy — have become some of the greatest enemies of today’s dissident Right. The people who resisted Friedman’s calls for lower taxes and free trade in 1980 are today doing the bidding of anti-white hate groups such as the Anti-Defamation League and are cheering on the Great Replacement.

It would be better to view libertarianism as a farm league for White Nationalism rather than a regrettable and embarrassing phase in many of our pasts. The problem is one of scale. Friedman sells his idea by promising smaller proportions of a bigger pie, which leads to greater wealth in absolute terms. But he forgets that power is a zero-sum game. If I get more of the pie, you must get less of it. This is what makes the world go round, and if one wishes to gain any of kind of real power, he’d be better served reading Machiavelli than Milton Friedman. Yes, Friedman offers excellent economic advice, but he does not delve deep enough into human nature to develop a comprehensive political philosophy.

Imagine a chemist trying to solve a problem in physics, and you have Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose.

[8]

[8]