The Suppression of the Maryland Moderates During the Civil War

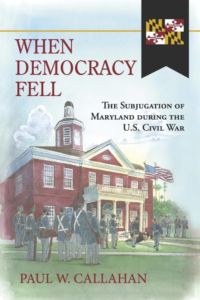

Morris van de CampPaul W. Callahan

When Democracy Fell: The Subjugation of Maryland During the U.S. Civil War

Pennsauken, N.J.: BookBaby, 2023

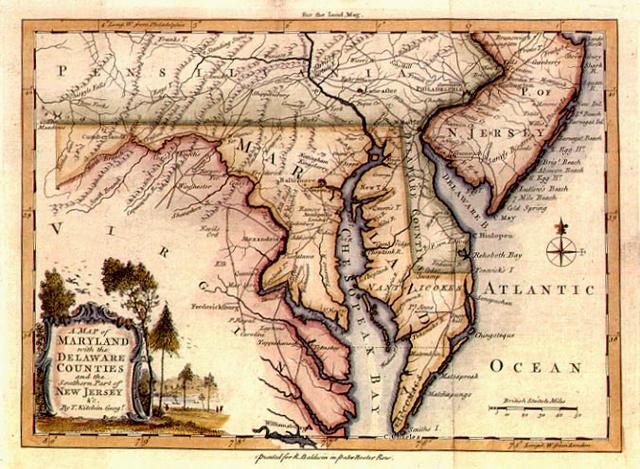

The impulse behind the colony of Maryland came from George Calvert, Lord Baltimore — a convert to Roman Catholicism. The Royal Charter for it was granted to his son Cecil in 1632. The colony’s purpose was to provide a refuge for English Catholics, and for a time Catholics dominated its government, although it was religiously tolerant toward Protestants.

In an example of demography being destiny, Maryland ceased to be a Catholic colony due to immigration from other parts of British North America. English Catholic settlers to Maryland turned out to be hard to come by, while English Protestants were already in North America in abundance.

Maryland received non-conforming Low Church Protestants who had been cast out of Virginia and Midlanders (often Quakers and allied sects) from Pennsylvania. The Elk and Sassafras rivers in Maryland’s northeastern corner consisted of settlements established by Swedes and Finns. An important group of Anglo Protestant immigrants were Puritans from New England, who led a revolt in 1689 against Maryland’s Catholic leadership.

The revolt in Maryland was politically related to the 1688 “Glorious Revolution” in England. The circumstances that led to the Puritan takeover were the result of issues stemming from a dispute between members of the British Royal Family rather than Europe’s Wars of Religion. Regardless, while the Puritans in Maryland adjusted Maryland’s political arrangement, the colony also didn’t become an outpost of Yankee New England.

After the Protestants took over Maryland, the colony’s state religion became Anglicanism, but there was tolerance of other sects, including Catholics. Anglo Catholics in Maryland remained wealthy landowners and community leaders, although they were barred from holding government offices for a time. One of the Anglo Catholics was Charles Carroll, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

As the colony developed, its mountainous west became populated by Scots-Irish and German settlers arriving from Pennsylvania. The state’s northern and central parts became an extension of the Quaker-dominated Midlands. Maryland’s portion of the Delmarva Peninsula and most of the Chesapeake Bay’s shores became an extension of Virginia’s Tidewater Culture, where upper-class Englishmen, often the second sons of aristocrats, established large plantations focused on growing tobacco.

Maryland’s political culture did not drift towards the radical and strident agendas of New England or the Deep South. Instead, it proudly retained its moderate political stance and jealously guarded its sovereignty. But eventually, the question of slavery became too big to ignore.

Paul W. Callahan’s When Democracy Fell takes a viewpoint on the Civil War which focuses on the cause of the war — slavery — rather than one which holds that the dreadful war was fought over which Anglo-American group would dominate the western territories, with slavery merely serving as a pretext for hostilities.

The final crisis which led to the Civil War was the breakup of the Democratic Party in the election of 1860. The Democrats fielded four candidates, the most rational of whom was the Northerner Stephen A. Douglas. Maryland’s Electoral College votes went for the Southerner John C. Breckenridge, but 45.1% of the votes went to the moderate Constitutional Unionist John Bell. Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, received 2.5% of the votes. While the Southern position in Maryland appeared strong, the moderate and Northern votes — for Lincoln, Bell, and Douglas combined — made up 54% altogether.

Maryland, along with the rest of the region between North and South, were the base for Constitutional Union voters. This included the Quaker Belt of North Carolina. North Carolina Quakers made up the backbone of the 1st US Volunteers, who would secure the Dakota Territory during the Civil War.

Maryland had slaves and plantations, but not to the same degree as the states of the Deep South. Many sub-Saharans in Maryland were already free, and the economy was thriving and diverse. The tobacco industry had declined, and many farmers were growing cereals and practicing crop rotation. This increased profits, was more sustainable, and lowered labor costs — as well as the need for slaves. Baltimore was an “it” city. It had a thriving port and many industries. The city was artistically significant, too. Edgar Allan Poe spent many years in Baltimore.

Lincoln traveled through Baltimore on his way to his inauguration, but he didn’t make a speech because there were rumors of an assassination plot against him. The plot was likely an invention of Allan Pinkerton, a detective who’d established a private investigation firm and who was looking for publicity. Had Lincoln made a goodwill speech in Baltimore, it is very likely that he would have won the residents over — but he didn’t, and they seethed with resentment.

Baltimore, April 19, 1861

The first shots in the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter, but there were no fatalities there. The first blood spilled in the war was in Baltimore on April 19, 1861 — but it was not the result of a battle, but a riot. Union troops were en route through the region, heading toward Washington, DC. Baltimore didn’t allow steam engines to cross the town, so the passenger cars had to be decoupled and then moved by horse to the other end of town. Baltimore residents also blocked the rails. Many were angry over Lincoln’s perceived snub and the use of federal troops to subdue fellow Americans. Thus, the Union troops disembarked and marched — encountering angry residents. Shots were fired, and there were casualties on both sides.

The day’s most politically significant event as far as the Marylanders were concerned was the killing of Robert W. Davis. Davis was out looking to purchase real estate and was unaware of the riot. So when Union troops passed by in a train, he raised a cheer for Jefferson Davis — and was shot by them.

Baltimore’s residents were outraged by Davis’ murder, purchasing guns in great abundance. Maryland’s Governor, Thomas H. Hicks, called up the militia, and they burned two bridges to keep further Union troops from traversing the state. Then, Hicks and Baltimore’s Mayor, George William Brown, sent a joint letter to Lincoln by special train imploring him not to send more troops through the city. Lincoln replied by letter the next day, promising that his troops would travel through Maryland, but would bypass Baltimore. General Winfield Scott would see to the particulars.

Northern newspapers editorialized against Baltimore, declaring the city’s residents to be traitors and encouraging the city’s destruction. While Lincoln appeared conciliatory, Union troops went by steamer to Annapolis, disembarked on the campus of the US Navy Academy, and then occupied the state’s capitol. Plans were drawn up to attack Baltimore, but Maryland’s political elite decided to stand down by early May. The militiamen were dismissed, and Maryland’s Confederate sympathizers slipped away to the South and joined the Confederate army.

The loss of the Confederate sympathizers strengthened the position of the Unconditional Unionists, who supported maintaining the Union by any means, including military force. Before then the Unconditional Unionists had been only a fringe political movement in Maryland.

The Suspension of Habeas Corpus

You can buy Greg Hood’s Waking Up From the American Dream here.

Lincoln swiftly moved against the state with force. American law, which is based on Anglo-Saxon Common Law and the Magna Carta, holds that a custodian of an imprisoned person must show that he is being lawfully detained and is under indictment for a violation of the law. This legal principle is called habeas corpus, and the custodian must provide a writ documenting the specific violation of the law to a judge. In the event of a rebellion, the US Constitution allows the government to suspend habeas corpus, however. But given that Maryland did not secede, it is questionable whether or not it was in fact in a state of rebellion in 1861.

Lincoln suspended habeas corpus regardless, and blocked the Maryland throughway that ran from the North to Washington, DC. Once this was done, Lincoln’s subordinates expanded the suspension to all of Maryland. The most important case resulting from this was the imprisonment of John Merryman. Merryman was an officer in Maryland’s militia who had cut some telegraph lines and burned several bridges. He was imprisoned, although he had been acting under lawful orders at the time. His case made its way to the US Supreme Court, and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney[1] ruled for Merryman.

Lincoln ignored the ruling, and it is even possible that he considered arresting and imprisoning Justice Taney, although that is debatable. What is certain is that Lincoln continued to expand the suspension of habeas corpus. It was only a matter of months after the citizens of Maryland lost their rights that the citizens of Maine likewise suffered arbitrary detentions. Soon, newspapers were shut down and editors were imprisoned, and 300 papers across the North were closed. Lincoln even imprisoned and deported a Congressman from Ohio. It is estimated that between 14,400 and 38,000 Northerners were imprisoned without a writ of habeas corpus.

Maryland Disarmed

Following the standing down of Maryland’s militia, Governor Hicks ordered that the weapons in the state’s arsenal should be turned over to the federal government. The reason given was the existence of alleged secessionist militias in the state, although it is clear that most genuine Confederate sympathizers had already left Maryland for the South in the weeks after the Baltimore Riot.

At the end of Governor Hicks’ term, he was commissioned as a Brigadier General in the Union army. His health was not good enough for active service, however, so he ran for the US Senate as a Unionist Republican — and won.

The arrests continued. One prominent Baltimore industrialist arrested was Ross Winans. Winans’ main enterprise was railroads, but he also manufactured other things, including cigar-shaped boats, ammunition, and pikes. His pikes had been used in the Baltimore riot. Winans was arrested without a writ of habeas corpus after the government of Virginia acquired a steam gun from his company. The local Union commander, General Benjamin Butler, would have executed Winans for treason after a military tribunal, but Lincoln ordered him released.

Around the same time, the Lincoln administration arrested Baltimore’s entire Police Board, the purpose of which was to ensure that the city held free and fair elections. Lincoln wanted Maryland’s elections to be a sure thing for him, and so moved to arrest Maryland’s legislators. But to do so, he needed to conduct a misinformation campaign via the press.

This misinformation campaign is strikingly familiar to others of the recent past. As the George W. Bush administration did during the lead-up to the Iraq War, the Lincoln administration used fear as a weapon. The War Department leaked stories about supposed large Confederate forces massing in Tidewater Maryland. Lincoln himself wrote articles under a pen name to stoke the flames.

At the center of this campaign was Major General Tench Tilghman of Oxford, Maryland. Tilghman was the grandson of Lieutenant Colonel Tench Tilghman, a hero of the Revolutionary War. He was alleged to be in command of a large force on Virginia’s eastern shore. Tilghman eventually issued a press release stating that he was doing so such thing, and while the media published it, they did not do so on the front page — and not until the damage had already done. Tilghman was arrested and held for a time, but later exonerated. His military career ended with him being used as a pawn in events which he could not control.

With so much clamor as a result of the misinformation campaign, it became easy for Lincoln to arrest those members of the Maryland State Legislature who had published a report decrying the suspension of habeas corpus in the state. 28 elected officials were eventually arrested, along with key civil servants in Maryland’s state government. Among those arrested was Frank Key Howard, the grandson of Francis Scott Key, who had penned the lyrics to what would become America’s national anthem during the War of 1812. Howard and the others who were arrested were kept in dismal conditions while confined. After he was released in 1863, Howard wrote a book called Fourteen Months in American Bastiles; the book’s publishers were imprisoned following its release.

Lincoln’s heavy-handed policy was risky, but it only backfired once, when his administration ordered the arrest of Judge Richard Bennett Carmichael because he was opposed to the Maryland legislature abjuring without a date for reconvening, which gave Governor Hicks a free hand to do as he pleased. Judge Carmichael also disliked the suspension of habeas corpus. In the late spring of 1862, men from the 2nd Delaware Infantry went to the courthouse and arrested him while he was sitting on the bench in a highly symbolic display of power. Judge Carmichael was then beaten unconscious by a man with a pistol and detained for six months; no charges were ever filed against him. This incident caused even more Marylanders to join the Confederacy.

You can buy Charles Krafft’s An Artist of the Right here.

Lincoln’s heavy hand in Maryland continued throughout the war, although it did ease up when Unconditional Unionists began to take political office across the state. They were only able to make gains because the Moderate Constitutionalists had been either imprisoned or suppressed by Union troops. During Maryland’s state elections in 1863, the Lincoln administration organized voter suppression tactics to ensure that the Unconditional Unionists won yet again, which made it appear that Lincoln’s local political supporters were in sync with Maryland’s voters. But the anti-Lincoln voters were identified before the election and prevented from voting.

It is likely that Maryland would not have seceded even without the occupation of its territory and the destruction of its democracy during the Civil War. Maryland fielded 19 infantry regiments for the Union and only two for the Confederacy. Additionally, it is clear that the Lincoln administration had many collaborators in the state, since most of the resistance came only from members of the political elite in response to the arbitrary detentions. Even on the occasions when the Confederate army invaded Maryland, no Marylanders joined their cause (although the Confederates weren’t looking for recruits).

Maryland Moderates, Machiavellianism, & Metapolitics

It is a great tragedy for America’s whites that Lincoln didn’t face a slave rebellion in 1861. Lincoln’s political, legal, and organizational genius would have allowed him to exploit the situation to end slavery and turn the United States into a genuine white ethnostate. While Lincoln ultimately became an abolitionist, he spent a great deal of time attempting to send America’s sub-Saharans overseas. Lincoln was a real white advocate. But as things turned out, Lincoln’s problem was whites in the South.

Lincoln’s Machiavellianism in Maryland was exceptional. He bought off those who could be bought, such as Governor Hicks, who went on to receive a General’s commission and a US Senate Seat. He identified his opponents and swiftly eliminated them, and he successfully persuaded a sufficient number of ordinary Marylanders to go along with him. He was able to do this because he retained capable people in government at a critical time, especially General Winfield Scott, and including the team of talented politicians in his cabinet. He was also able to recruit an enormous army of valorous men who were willing to do violence on his behalf.

Lincoln would probably say that his heavy-handed measures were justified given that he successfully suppressed any budding rebellion in Maryland in wartime. Although there were arrests and other injustices, Maryland’s fate during the war ended up being far better than that of those places which were fought over again and again.

Maryland’s political moderates were put in the unenviable position of trying to maintain neutrality while being stuck between two powerful belligerents. Maryland’s problems were compounded by the fact that its moderate political elite didn’t practice metapolitics on the same level as the Yankee abolitionists and the Southern Fire-Eaters in the decades before the war.

Maryland’s political elite at the time consisted of the family members of those such as Francis Scott Key, who had reflected America’s worldview at the time of the War of 1812, when the balance between free and slave states had been (temporarily) settled. There were also no intense religious revivals to give rise to an uncompromising bloc of voters who were willing to destroy themselves and their fellow countrymen over the status of racial aliens. Like the conservatives of the 2020s, they probably thought their ideas were so obviously desirable and practical that they failed to try to propagate them — and thus the “woke” radicals of the day led America into an episode of collective insanity.

Note

[1] Interestingly, during the 2020 Summer of Floyd, monuments to Justice Taney, who had taken a stand against arbitrary arrest and imprisonment, were removed. The moderate Constitutional Unionists of Maryland were industrious, pro-white, America First sorts of people who were justly and quietly ending slavery in their own state. Justice Taney himself had freed his slaves when he was a young man. Removing Taney’s monuments is as much a symbolic destruction of the values of industry and America First as a rejection of his ruling in the Dred Scott Case.

The%20Suppression%20of%20the%20Maryland%20Moderates%20During%20the%20Civil%20War

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Related

-

Get to Know Your Friendly Neighborhood Habsburg

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

The Big Implications of a Small-Town Election

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

2 comments

George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, was not a Catholic convert; the Calverts had always been Catholic. Like their Arundell in-laws, and the senior English noble family of that time and now (that of the Duke of Norfolk), they were what the government referred to in Elizabethan and Jacobean times as “recusants,” families who chose not to sell their birthright for a mess of pottage. Of course they often had to be discreet about this.

All the historical sources say he converted.

https://www.pghistory.org/PG/PG300/begin.html#:~:text=Long%20attracted%20to%20Catholicism%2C%20Calvert,and%20acknowledge%20the%20fact%20publicly.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.