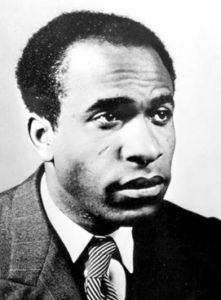

Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks:

A Primary Text of Post-Colonial Jive

Part 1

Beau Albrecht

2,877 words

Part 1 of 4 (Part 2 here)

Frantz Fanon was a black author who mostly wrote about being black. (Of course, right?) The celebrated skintellectual began as a citizen of Martinique. He volunteered for the De Gaullist forces during the Second World War. Then he got a university education on scholarship in Lyon and became a psychiatrist.

What would he have done had he stayed in Martinique — editing some sad Leftist rag in Fort-de-France, perhaps? If that didn’t work out, then like many other islanders he could’ve earned his daily bread with a machete, chopping down bananas or sugar cane all day under the tropical Sun. Still, the career boost did not inspire him to appreciate French society, to say the least. The French were entirely too kind when they let him in, since he didn’t belong there. During the Algerian Civil War, he began sympathizing with the National Liberation Front (FLN). (Of course, right?) He eventually joined the terrorists.

He involved himself with other bomb-chucking Marxist “liberation movements” in Africa during his later travels, the likes of which helped make the Dark Continent the shining beacon of enlightenment that it is today. Despite Fanon’s colorful adventures as an AK-47-toting psychiatrist, he’s best known as a writer, who is still lauded as the bees’ knees by Leftist academia. Had he survived his 1961 bout with cancer, it’s a mathematical certainty — and I can prove it on a freaking abacus — that he eventually would’ve become a Parisian professor teaching the latest nuances of anti-white studies. With luck, thanks to Good Liberal Opinion, the former terrorist would’ve racked up a list of awards, medals, titles, honorary degrees, streets and buildings named after him, and assorted honors and dignities longer than Charles Manson’s rap sheet.

One of his two best-known books is Black Skin, White Masks, published in 1952, shortly before his sojourn in Algeria. It was originally intended to be a doctoral dissertation called “Essay on the Disalienation of the Black,” but someone at the University of Lyon decided that megatons of minoritist moaning missed the mark for a significant contribution to human knowledge. Surely that took balls of steel! I can hardly imagine anyone in today’s academia daring to give it anything other than slobbering praise. As for Fanon’s reaction to his magnum opus being rejected, I only can imagine it was perhaps something similar to the agonized howling that reverberated dreadfully throughout the cosmos when Heavenly Father cast Lucifer down into Outer Darkness.

As for Fanon’s farewell oeuvre, The Wretched of the Earth, it included discussion of the virtues of ethnonationalistic sovereignty and (ahem) aggressively asserting it by any means necessary. I’ll decline to review that one, lest I start saying lots of bad-optics things which my editor wouldn’t appreciate. After all, I actually might find the points to be universally applicable. Why should active resistance be okie-dokie only for Leftist-approved cuddly guerrillas, such as backward camel cavaliers like the FLN or Marxoid moon crickets like the African National Congress (ANC)? As that Right-wing extremist militia nut John Fitzgerald Kennedy said, those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make you-know-what inevitable.

Ever the graphomaniac, Fanon’s texts — generally essays and collections thereof — are canonical in the Post-Colonial Studies racket and related cultural Marxist academic boondoggles. To this day, Leftist professors use them to demoralize their white students and encourage truculence in their black students. (Of course, right?) Effectively, it’s revenge from beyond the grave for the spurned doctoral dissertation! I first saw Black Skin, White Masks in a university bookstore back in the days of yore. After flipping through it, I wasn’t so impressed, but I’ll give it a thorough reading this time. I present this review in the hopes that it’ll be useful to self-respecting white students who unfortunately are forced to read it, to help them keep their wits intact while they endure a deluge of demoralization propaganda.

Historical context

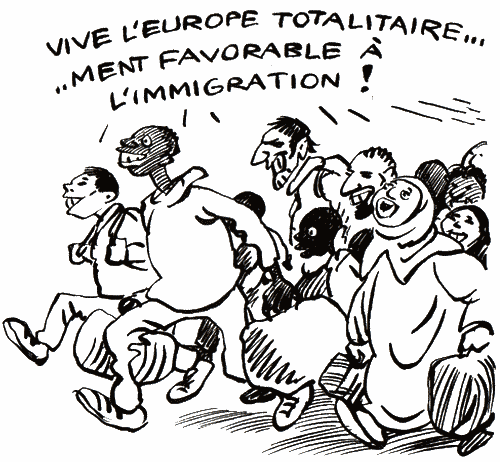

CHARD: “Une Europe totalitaire . . .” Decolonization became colonization the other way.

Colonialism was still ongoing in 1952, though on the decline. For one thing, the War to Make the World Safe for Democracy had weakened Britain and France severely, making it difficult for them to hold on to their overseas territories. In Vietnam France passed the torch to the United States, of course leading to our archetypal spit-in-your-eye war. India’s secession in 1948 was likewise a major loss for the British Empire. The Mau-Mau Rebellion was a victory for the British, but later, the government threw their people in Kenya under the bus. In the coming decades, “liberation movements” supported by the Soviet Union and the ChiComs hastened decolonization. The Deep State’s department handling wetwork — destabilizing countries on behalf of greedy corporations — and dope smuggling (better known as the CIA) did its bit as well. All these rival forces made for a three-way intra-Leftist competition, and none were particularly favorable to whites.

You can buy Beau Albrecht’s Space Vixen Trek here.

There’s nothing wrong with independence and sovereignty as such. The problem is that many of these former colonies weren’t yet ready for home rule. Moreover, terrorists waving AK-47s tended to do a lousy job of it when they got in charge of these newly-independent countries; thugs promoted to politicians are still thugs. Since then, all too often massive amounts of Western aid meant to relieve Third World poverty were embezzled by local dictators. In fact, I have a buddy in Nigeria trying to help me get $25 million of that swag!

Despite the constant drumbeat of anti-colonial rhetoric in Black Skin, White Masks, there was actually some nuance about what was or wasn’t a colony. Martinique became an overseas département of France in 1946 — that is to say, its status became the equivalent of present-day Hawaii, rather than being more like Puerto Rico. I’m not sure what the French are getting out of the arrangement, though. Fanon’s complaints about colonialism in his homeland were therefore a little out of date. Moreover, blacks were no more native to the Caribbean than whites, though that doesn’t prevent Fanon from crying in his beer. Actually, blacks ultimately benefitted from colonialism by expanding their territory, even if they were only along for the ride.

As for Algeria, it was long considered a part of France at the time of Fanon’s writing rather than as a colony. An ugly civil war began soon after and dragged on until 1962, ending when Charles de Gaulle sold out Algeria’s French population, dispossessing them. This also produced a wave of non-white migrants, much like so many other foreign policy bungles in the Western world since the second half of the twentieth century.

Many Algerians congregated in Paris, becoming the first of the vast masses of vibrant unassimilables. Since then they’ve refused government offers to pay them to repatriate. Now the cultural enrichers have much greater numbers, most forming a lumpenproletariat that lives in housing projects in outlying slums. According to what I’ve heard, most residents of these banlieues do little other than collect welfare checks and breed. Sometimes Parisian race riots break the monotony — a phenomenon that (surprise!) was absent prior to multiracialism. Apparently, the welfare entrepreneurs are unhappy about being oppressed.

Opening matter

The 2008 edition has a Preface by Ziauddin Sardar. The illustrious scholar, born in a remote Pakistani border outpost, is now considered to be among Britain’s greatest minds. This should therefore be a smoking overture here. Early on we have:

Fanon’s anger has a strong contemporary echo. It is the silent scream of all those who toil in abject poverty simply to exist in the hinterlands and vast conurbations of Africa. It is the resentment of all those marginalized and firmly located on the fringes in Asia and Latin America. It is the bitterness of those demonstrating against the Empire, the superiority complex of the neo-conservative ideology, and the banality of the “War on Terror.”

Whoa — check out those riffs! Just a couple of paragraphs into the opening band, and Led Ziauddin is strumming the power chords hard! It’s in the key of G(uilt)-major, naturally.

Black Skin, White Masks charts the author’s own journey of discovering his dignity through an interrogation of his own Self — a journey that will not be unfamiliar to all those who have been forced to endure western civilization.

I should add that Western civilization’s ruling class and media establishment allowed Ziauddin Sardar to move from the impoverished and politically unstable Third World country of his birth to the bustling metropolis of London, gave him a university education, granted him a professorship, made him a television celebrity, published his books, printed his newspaper columns, and anointed him as a public intellectual. Last but certainly not least, our greatest minds developed the mass communications technology and infrastructure that he uses to complain about us bitterly. Beastly, aren’t we?

A brief biography follows, and then an analysis of the book’s themes for those who are actually interested in making sense of Fanon’s overheated blather. This is already looking like a doozy:

When a black man arrives in France it is not only the language that changes him. He is changed also because it is from France that he received his knowledge of Mostesquieu [sic.], Rousseau, and Voltaire, but also because France gave him his physicians, his department head, his innumerable little functionaries. At issue is thus not just language but also the civilization of the white man.

So he’s eaten up with envy because we developed the Age of Enlightenment, modern medicine, and infrastructure. Fine — then leave, if it’s so unbearable. Oops, did I just say that?

Just because a particular discipline or a discourse is accepted or practiced throughout the world, it does not mean that discipline or discourse is universally valid and applicable to all societies. After all, as I have written elsewhere, burgers and coke are eaten and drunk throughout the world but one would hardly classify them as universally embraced, healthy and acceptable food: what the presence of burgers and coke in every city and town in the world demonstrate is not their universality but the power and dominance of the culture that produced them.

That one is a telling insight into the plucky commentator himself, as are some points he makes later. He’s unfortunately failing to see a key distinction: Authentic white culture is not identical to globalist mass culture or its artificial cosmopolitanism. If he doesn’t care for junk food being sold all across the planet, that wasn’t us; he should take it out on the corporate monopolies. Me no Alamo; me no Goliad! On that note, Western civilization is not the same as Clown World. And finally, notwithstanding its democratic window dressing, The System is not a legitimate government of the people; it’s a dildocracy imposed by corrupt oligarchs.

You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s Western Civilization Bites Back here.

More to the point, Sardar correctly sees that the ugly globalist leviathan is worming its tentacles into his beloved Third World. Still, it’s really done far more damage to the West. What he doesn’t see is that our so-called elites are a parasitical exploiter class that has chosen to wage war against the public. He thinks he’s attacking the leviathan when he trash-talks Western civilization, but again, who’s handing him the microphone and using him as a mouthpiece? If he wants to find out who’s boss, he can take his Muslim fundamentalism to the next level, telling his audience that women belong in burqas, gays should be thrown from rooftops, and Israel should be pushed into the sea. Then this public intellectual praised to the skies will find himself cancelled faster than J. K. Rowling. Who’s yo daddy, Ziauddin?

More follows about Fanon’s odd invocation of universalist principles, after bitterly rejecting European intellectual traditions such as universalism. The reasoning sounds oddly similar to the hardcore followers of the nutty antinomian rabbi Shabbatai Zvi defending his apostasy as fulfilling a higher purpose. Then there’s this:

Racism, both in its most blatant and incipient forms, is the foundation of Fortress Europe — as is so evident in the reemergence of the extreme right in Germany and Holland, France and Belgium, as well as Scandinavia, and the discourse of refugees, immigrants, asylum seekers and the Muslim population of Europe. Direct colonial rule may have disappeared; but colonialism, in its many disguises as cultural, economic, political and knowledge-based oppression, lives on.

Cry me a river, dude. He’s been going on and on about the evils of colonialism. What makes him think we want our own countries colonized by vibrant Third World troublemakers and welfare entrepreneurs? Although Sardar himself is neither of those things, it’s remarkable that he dislikes the society that embraced him.

But wait! There’s more! The book still includes the foreword to the 1986 edition by the studly studmuffin of Post-Colonial studies, Homi K. Bhabha. Surprisingly, he found some coherent threads emerging from Fanon’s career of pouting:

The body of his work splits between a Hegelian–Marxist dialectic, a phenomenological affirmation of Self and Other and the psychoanalytic ambivalence of the Unconscious, its turning from love to hate, mastery to servitude. In his desperate, doomed search for a dialectic of deliverance Fanon explores the edge of these modes for thought: his Hegelianism restores hope to history; his existentialist evocation of the “I” restores the presence of the marginalized; and his psychoanalytic framework illuminates the “madness” of racism, the pleasure of pain, the agonistic fantasy of political power.

Hoo doggie! If I could write like that, I’d have a cushy job as a Harvard postmodernist professor, too!

“What does the black man want?” Fanon insists and in privileging the psychic dimension he changes not only what we understand by a political demand but transforms the very means by which we recognize and identify its human agency.

Roger that. Much more of this vague pomo-babble follows. When it comes to good literature, the words are to be savored. With Homi Bhabha’s Preface, it’s like chowing down on a tasty bowl of rubber bands. Is he trying to say as little as possible with as many words as possible which make the least possible sense? If so, he succeeds brilliantly:

By following the trajectory of colonial desire — in the company of that bizarre colonial figure, the tethered shadow — it becomes possible to cross, even to shift the Manichean boundaries. Where there is no human nature hope can hardly spring eternal; but it emerges surely and surreptitiously in the strategic return of that difference that informs and deforms the image of identity, in the margin of Otherness that displays identification. There may be no Hegelian negation but Fanon must sometimes be reminded that the disavowal of the Other always exacerbates the “edge” of identification, reveals that dangerous place where identity and aggressivity are twinned.

This is why the opening matter drags on so much. Homi Bhabha actually starts making a little sense toward the end — I’m guessing that part was the first draft — but all told, the Introduction was an epic slog, with nothing too remarkable to show for it. The Sierra Club should be angry that trees died for this blather. Come to think of it, the same could be said for the entire book.

Finally, there’s the author’s own Introduction. Fanon starts off sort of detached and above-it-all, though obviously holding down the lid on a volcano of racial hatred while pretending he isn’t. For example:

From all sides dozens and hundreds of pages assail me and try to impose their wills on me. But a single line would be enough. Supply a single answer and the color problem would be stripped of all its importance.

What does a man want?

What does the black man want?

At the risk of arousing the resentment of my colored brothers, I will say that the black is not a man.

There is a zone of nonbeing, an extraordinarily sterile and arid region, an utterly naked declivity where an authentic upheaval can be born. In most cases, the black man lacks the advantage of being able to accomplish this descent into a real hell.

Passages like this are reminiscent of a guy at a train station nonchalantly making idle chit-chat while his thumb caresses the switch for his suicide vest. Back in the day, surely this dude was the life of the party.

In an age when skeptical doubt has taken root in the world, when in the words of a gang of salauds[1] it is no longer possible to find the sense of non-sense, it becomes harder to penetrate to a level where the categories of sense and non-sense are not yet invoked.

The black man wants to be white. The white man slaves to reach a human level.

D’awwww! Earlier, I thought Between the World and Me was the penultimate in black bellyaching, but no longer. The fifth chapter especially excels in butthurt. Even as I finished the preface, it became clear that Frantz Fanon practically made an Olympic sport out of Afro-dyspepsia.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Note

[1] A French insult generally equivalent to “dirty bastards.” For our many Turkish readers, consider it similar to pislikler.

Frantz%20Fanonand%238217%3Bs%20Black%20Skin%2C%20White%20Masks%3A%0AA%20Primary%20Text%20of%20Post-Colonial%20Jive%0APart%201%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 1: Nowa Prawica przeciw Starej Prawicy

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?