Having already published two extensive articles on The Prisoner (see here and here), I didn’t expect to ever write about the series again. But times have changed, and so has The Prisoner. Works of art are living things, and their meaning changes over time. This ultimately has little to do with the artist’s intentions. That The Prisoner had changed was brought home to me one evening when, on a whim, I chose to revisit an episode I had always disliked.

“A Change of Mind” was first broadcast in the United Kingdom on December 15, 1967. Roy Rossotti had originally been hired as director, but McGoohan quickly became dissatisfied with his work and fired him after lunch on the first or second day of shooting (accounts differ). McGoohan took over direction himself, but is credited as “Joseph Serf.” The result is a taut, fast-paced episode on a par with McGoohan’s earlier directorial effort, “Free for All.” One drawback, however, is that “A Change of Mind” is heavily studio-based. Although footage was shot on location in Portmeirion, some of it is stock footage, and some shots feature doubles standing in for McGoohan and the other actors. Portmeirion exteriors are simulated throughout the episode via studio sets and backdrops that are not entirely convincing.

The problem I always had with “A Change of Mind,” however, had nothing to do with its lack of location work. I had always thought that the script (by Roger Parkes, a prolific TV writer who specialized in thrillers) was a trifle heavy-handed, especially in its apparent attempts at social commentary. The episode’s plot involves Number Six learning that a Village committee holds the power to declare rebellious inmates “unmutual.” This involves social ostracism, and, in particularly stubborn cases, a procedure known as “instant social conversion”; i.e., lobotomy, sometimes referred to in the UK as “leucotomy.” This term is actually used in an earlier episode, “Checkmate,” in which a female psychiatrist recommends that a leucotomy be performed on Number Six.[1]

Predictably, “A Change of Mind” involves Number Six being declared unmutual and condemned to instant social conversion. But, as I shall reveal later on (spoiler alert!), all is not as it seems. The premise of the episode is quite dramatic — and frightening. But I had never been impressed with how it was treated in the dialogue and characterizations. The villagers are depicted as so mindless and conforming that parts of the episode seemed downright comical, undercutting the horror. The villagers also exhibit a degree of emotional volatility that I found unconvincing — especially when they become enraged at Number Six. And the whole concept of the “unmutual” seemed to me to be a rather thinly-disguised rebranding of Orwell’s “unperson.”

But, as I said earlier, times have changed — and now, incredibly, I have come to view “A Change of Mind” as a remarkable prophecy of today’s madness. Among other things, the treatment of the unmutual now seems like an anticipation of the “social credit system” perfected by the Chinese, and now being not-so-slowly introduced into the West. And, on further reflection, the unmutual is clearly quite different from Orwell’s unperson. I’ll now consider the episode in more detail, then touch very briefly on a few other episodes that have taken on new significance, and end with some concluding reflections on The Prisoner’s power to inspire those of us on the Dissident Right.

The episode opens with a glimpse of Number Six’s workout routine. He has constructed a makeshift gymnasium in the woods, including a high bar and a heavy bag for punching. Number Six appears to be impressively fit (though it is clear in several shots that the man doing turns on the high bar is not Patrick McGoohan). Two young toughs appear and begin to taunt Number Six for choosing to work out in the woods rather than at the Village gymnasium like a “public-minded citizen.” They accuse him of being “anti-social.” The intimidation soon becomes physical — much to the two thugs’ chagrin, as Number Six quickly bests them. As one slinks away, tail between his legs, he whimpers, “You’ll face the Committee for this!”[2]

What exactly is this Committee? It’s never been mentioned in earlier episodes, but it is the “Citizens’ Welfare Committee” (a fact revealed in the original script). With a name like that, you know that its purpose must be just the opposite — like the French Revolution’s “Committee of Public Safety.” A meeting is convened (apparently at the Village Town Hall), and Number Six is duly summoned. When he arrives, he finds himself in a waiting room filled with people who are to be seen by the Committee. At the center of the room is a lectern featuring a speaker broadcasting the deliberations, which are taking place in the chamber next door. Number Six seats himself next to a young woman, Number Forty-Two (played by Kathleen Breck), who continually weeps. The Committee is in the midst of hearing the case of Number Ninety-Three, who is referred to by a bland voice as “disharmonious” and unwilling to “work for the community.”

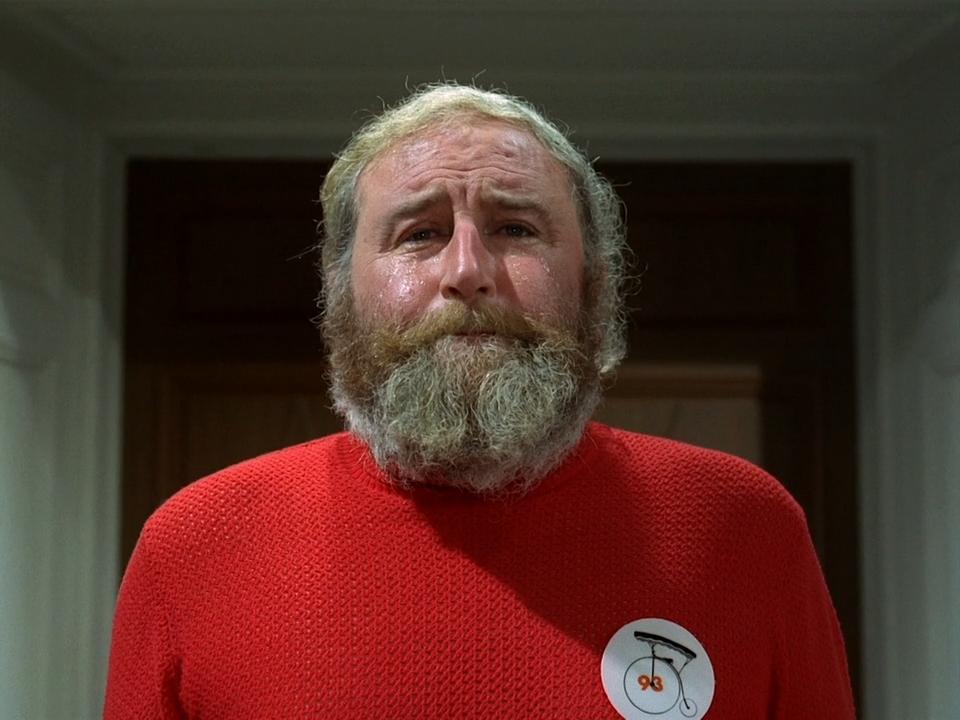

The voice also mentions the upcoming cases. Number Six is described as “seriously in need of help,” and Number Forty-Two as “in a permanent state of depression.” As we will see, the voice coming from the speaker does not belong to any of the Committee members, and, even weirder, it seems to originate from a pre-recorded tape. Number Ninety-Three is told that the only way to redeem himself is to publicly confess his shortcomings. “We will tell you what to say,” the voice volunteers. Ninety-Three then emerges from the Committee chamber and moves to the lectern. He is a large, bearded man whose eyes are wet with tears. The speaker prompts him, and Ninety-Three repeats its words. “They’re right, of course. I’m inadequate! Disharmonious.” He works himself up into a frenzy of self-abasement, finally screaming, “Believe me! Believe me!”

Obviously, Communist show trials are being parodied here. Elements of Village tyranny depicted in “A Change of Mind” have a distinctively Chinese flavor — a fact which has been commented on by others. This is no surprise, as Mao’s Cultural Revolution was in full swing by this point, and writer Roger Parkes may have drawn inspiration from news reports concerning it. But we can just as easily liken the scene described above to the desperate apologies proffered today by the casualties of “cancel culture” — which are a kind of ritual public humiliation that never results in what the penitent desires: forgiveness, and a restoration of status and livelihood.

Number Six is then called to enter the chamber, which is a slight revision of an impressive set seen before in “Free for All.” The Committee consists in nine old men in top hats seated at a circular, green beige table that forms a ring around a special chair for the accused. Number Six is immediately asked to confess, but there is no overt harassment or hostility from the members. Instead, they appear benign, and insist that they only wish to help him. “All we ask is for your complete confession,” says the recorded voice. Needless to say, Number Six is uncooperative, and makes light of the proceedings. Resolving to investigate him further, the Committee adjourns for a tea break. When Number Six reenters the waiting room, the speaker on the lectern is replaying the recorded confession of Number Ninety-Three. The suggestion is that Number Six is supposed to repeat his words. Unsurprisingly, he does not. As he exits, we see that Forty-Two is still weeping.

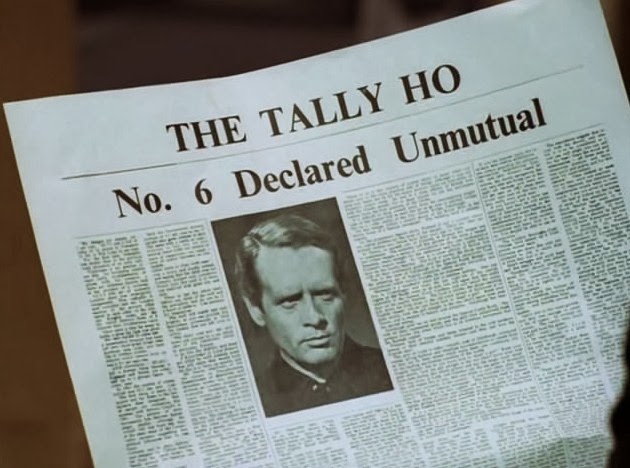

Throughout the scene, Number Six’s manner has been cavalier and ironic. On making his way back to his cottage, however, we begin to see signs that his attitude may be changing. He offers a friendly greeting to an old woman, someone of whom he has clearly grown fond, but she completely fails to acknowledge him. At just this point, the music becomes ominous. Then a man turns a corner and, seeing Number Six, moves swiftly away from him. Our hero is handed a copy of the Village newspaper, The Tally Ho, by a vendor who clearly disdains having to deal with him at all. The newspaper’s headline reads, “No. 6 for Further Investigation.” We cannot tell whether he is disturbed or simply annoyed by these developments. Perhaps both.

On entering his cottage, Number Six crumples the newspaper and tosses it into the fireplace. He is surprised when he looks up and sees that the new Number Two (John Sharp) has come for a visit. A fat man who speaks in sinister, sibilant tones, he attempts to warn Number Six that he must take the Committee’s investigation seriously. “Be careful. Do not defy this committee,” he says. “If the hearings go against you, I am powerless to help you.” At this point, Number Eighty-Six enters. Played by Angela Browne, she is a pretty blonde in her late twenties, but her demeanor is icy and officious. She has been assigned to Number Six, apparently as his social worker. And she insists that she is well qualified for this job, since she had at one time been investigated for being “disharmonious.”

Eighty-Six chastises our hero for his frivolous attitude toward the Committee, and says that the “social group” is his only hope. We meet this group in the next scene. They are seated outside, some on canvass chairs. There are eight members, including Number Eighty-Six. All are young, and the script specifies that “their remarks are made with the restrained earnestness of undergraduates.” Prominent among them is Forty-Two, the girl seen earlier, only now she has stopped crying. In fact, the group discussion seems to have something to do with her. Significantly, one of the most vocal members appears to be Chinese. “There can be no mitigation!” he cries. “We all have a social obligation to stand together!”

Forty-Two appears to be defending herself against an accusation of anti-social behavior. “No exceptions!” cries another member, who seems to be Spanish. Addressing himself to Forty-Two, he says, “All right, so you say you’re a poet. You were composing. You failed to hear Number Ten’s greeting.” “Neglect of social principle!” snarls the Chinaman. What we are witnessing, of course, is a Maoist “struggle session.” Both bored and amused by the proceedings, Number Six, who has been standing at the periphery, begins clapping. He then offers one observation: “Poetry has a social value.” At this, the group members erupt in righteous indignation. They accuse Number Six of attempting to divide them, of stopping them from trying to “help” Number Forty-Two.

“You’re trying to undermine my rehabilitation, disrupt my social progress!” she shouts, rising from her chair in fury. “Strange talk for a poet,” Number Six remarks. And indeed it is — but it is also wholly unsurprising for a society in which all the arts have been hijacked for the purposes of propaganda, and all artists are mindless apparatchiks. The group then begins shouting epithets at Number Six — “Reactionary!” “Rebel!” “Disharmonious!” — whereupon they immediately scatter. Apparently, the “social group” is uninterested in debate. Coupling the accusations of “reactionary” and “rebel” is particularly significant here. The former term is normally used by the Left against the Right, and the latter by Right against Left. But when the Left is in power, it becomes the establishment and rebellion becomes reaction. As Paul Joseph Watson, himself a Prisoner fan, has put it, “Conservatism is the new counterculture.”

Number Six disappears into the woods, leaving Eighty-Six to fret in her chair. Emerging onto the road, he finds three sturdy-looking men in white coats waiting to drive him to the hospital for a medical exam. Sizing them up, he decides it would be easier to cooperate, and the scene cuts to the village hospital. The medical exam itself is quite routine, but on leaving the examination room Number Six notices a room labelled “Aversion Therapy.” A man is visible through the porthole window in the door who is strapped to a chair, his body covered in electrodes. With shades of A Clockwork Orange (the novel was published in 1962), he is being forced to watch a film. When Rover appears onscreen (Rover is the strange, roaring balloon that guards the Village), the man apparently receives an electric shock. When the image is replaced by one of Number Two, the current switches off and the man smiles in gratitude.[3]

Appalled by this abuse, Number Six tries to force the locked door open. “Relax, fellow. Relax,” says a voice behind him. It belongs to a middle-aged patient in his pajamas, seated outside one of the doors. When Number Six speaks to him, it becomes quickly apparent that the man himself is quite relaxed — too relaxed, in fact. The script refers to him as “Lobo Man,” short for “lobotomy.” “I’m one of the lucky ones, the happy ones,” he says, and as he speaks he touches his temple, where we can clearly see a small, round scar. “I was unmutual,” he explains.

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here.

With cinematic inevitability, the very next scene returns us to the Citizens’ Welfare Committee, where Number Six is now officially “cancelled” — i.e., declared unmutual. This decision is made, so the Chairman announces, based on the recommendation of the “social group” — in other words, the group of hysterical young SJWs seen earlier. Number Six is warned that if any further complaint is lodged against him, he will be recommended for “instant social conversion.” When he leaves the Town Hall, we see that other villagers move swiftly away from him.

The Village’s cheery female voice (actress Fenella Fielding) announces that Number Six has been declared unmutual “until further notice.” Any reports of anti-social behavior from Number Six are to be forwarded to something called the “Appeals Subcommittee.” As we shall discover, the unmutual is indeed distinctively different from Orwell’s “unperson.” The unperson completely disappears and everyone acts like he never existed. Official records, including newspapers, are even revised so as to remove any mention of him. The unmutual, however, remains in society but is shunned — and he is denied rights and privileges available to other citizens.

Upon entering his cottage, Number Six finds it strangely silent. The radio and television, which have no off switch, have been remotely deactivated. He tries the phone and finds that there is no dial tone. This is the point in the episode at which the parallels to the “social credit system” now go into high gear. The seeds for this were actually planted in the “writers’ guide” prepared when the series was still in the planning stages. There we read that “[our hero] has to have a Security Number to warrant an issue of village currency to enable him to buy food supplies, clothing, or even a glass of beer in the village pub.”[4] This is established in the first episode when Number Six, having just arrived in the Village, attempts to make a phone call. The operator asks him, “What is your number, sir?” In his bewilderment he searches the phone, thinking a number must be printed on it, and says, “Haven’t got a number.” The operator responds sharply, “No number, no call,” and immediately hangs up.

Number Six is not alone in the cottage for long: A group of dour women arrives at his door, claiming to represent the Appeals Subcommittee. All are dumpy and middle-aged, save our old friend Forty-Two. “You certainly get around,” Number Six says to her. The woman who seems to be the leader admonishes him not to sneer at Forty-Two. “To volunteer for social work of this nature requires considerable moral courage,” she explains. As in today’s society, Forty-Two has apparently parlayed her victimhood (her chronic depression and weepiness) into a position of moral authority and social power. When Number Six continues to respond with sarcasm, the women depart. Watching him on closed-circuit TV, Number Two says to the Supervisor, “Now let’s see how our loner withstands real loneliness.”

Number Six walks to the Village café and orders a coffee, but the waiter refuses to acknowledge him. Then the other patrons rise from their chairs and move to one side, where they simply stare at Number Six, their faces blank, not registering hostility or any other emotion. When Number Six arrives back at his cottage, he finds that the women have returned. This time their tone is shrill, bordering on hysteria. (It is significant, of course, that the most fanatically conforming villagers are women.) “Unmutualism, Number Six,” says the one heard earlier, “more, you must now agree, than just a game!” Referring to the patrons in the café, Forty-Two says, “They are socially-conscious citizens, and are provoked by the loathsome presence of an unmutual.”[5]

“They are sheep,” Number Six responds, pointedly. (It’s a line that, for some reason, sent shivers down my spine when I saw the episode as a boy.) Her tone rising in hysteria, the first woman cries, “Enough! He insists on rejecting our offer of help.” And she adds, ominously, “There remains but one course open to us.” Just after the women have stormed out, the phone rings. Number Two is on the line. “I warned you,” he says. “The community will not tolerate you indefinitely.”

He assures Number Six that after “conversion” he will have “lasting peace of mind.” Our hero immediately assumes that he means they are going to drug him, but Two dismisses this. “Would drugs be lasting? What would be lasting,” he says, drawing his words out for effect, “is isolation of the aggressive frontal lobes of the brain.” Then the line goes dead. It is a chilling moment, and Number Six is uncharacteristically rattled by it. In keeping with the eerie immediacy we have come to expect of the Village, the announcer is heard telling the inhabitants that Number Six’s “conversion” will be televised. All the while, he clearly suspects that this is some kind of fakery on the part of his captors, but he cannot be sure.

Number Six steps outside the cottage and sits down at a nearby table, looking apprehensive, as if waiting for the next shoe to drop. We then hear some commotion from the villagers, who have been unusually quiet since Number Six was declared unmutual. A large group suddenly appears, and in the lead are the Appeals Subcommittee’s female members, carrying big umbrellas. “Splendid, Number Six,” says the same shrill woman heard earlier, with sinister glee. “Just in time for the procession!” Like a flock of Karens descending on the unmasked, the women then begin beating Number Six with their umbrellas.

He tries to escape, but the men in the crowd soon grab him and, holding tight, drag him to the hospital. It is only the second time in the series that we have seen the villagers behave violently (the first was the conclusion of the carnival scene in “Dance of the Dead”). Once again we are reminded of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, in which thought criminals were often ritually paraded through the streets and physically abused. All that is missing is a sign around Number Six’s neck identifying him as unmutual.

As soon as he is delivered to the hospital, our hero is injected with a drug that renders him immobile but leaves him fully conscious. He is then wheeled into an operating theater, where we are surprised to find Number Eighty-Six. We were given no indication earlier that she is a scientist, but not only does Eighty-Six seem to be the lead technician, but she even explains the entire procedure for those watching, in the bland tone of a BBC documentary presenter.

The lobotomy, we learn, is to be accomplished not with an icepick and a mallet, but using ultrasonic waves. On consulting Roger Parkes’ original script, I was surprised to find that he included a lengthy description of the theory behind this (not in the dialogue, but solely for the cast and crew reading the script). I had always assumed that the episode was presenting us with a science-fiction lobotomy, but it only took a few moments on Google to establish that lobotomy via ultrasound was actually developed in the 1950s. It is likely, however, that some of the equipment depicted in the scene has been given the usual gee-whiz Prisoner treatment.

I do not think I need to say much at this point about the abuse of psychiatry by totalitarian regimes. My readers are probably already well aware of the record of such abuse in the Soviet Union, Mao’s China, and other Marxist utopias. Soviet dissidents were often hospitalized with bogus diagnoses such as “sluggish schizophrenia,” drugged, often confined for life, and, in some cases, lobotomized. Such practices continue to this day in China. But I probably also do not need to remind my readers that the political weaponization of psychiatry has not been confined to the East. Racism, for example, has been declared a mental illness (see here and here, for instance) — while simultaneously the same “experts” have declared that race does not exist.[6] Donald Trump and his supporters have been declared mentally ill. There are many other such examples. The Authoritarian Personality, the notorious 1950 sociological “study” by Theodor Adorno and others, pathologized everyone to the right of Lenin. The weaponization of psychiatry by the Left has a very long history.

In any case, the lobotomy scene in “A Change of Mind” is the highlight of the episode, and one of the most chillingly effective scenes in the entire series. Number Six is strapped onto a gurney, his head secured in a vice, and the “link point” of the frontal lobes is located. The scene ends with Number Six’s cranium apparently being bombarded with ultrasonic waves, at which point he loses consciousness. He wakes up fully clothed in a hospital bed with a Band-Aid on his right temple, feeling unusually relaxed. A kindly doctor advises him to keep calm, saying that excitement and exertion are “not for you anymore.” He is then placed in the care of Number Eighty-Six.

When they leave the hospital, a crowd of villagers is waiting for Number Six. They are not violent this time, and instead greet our hero warmly. With his will apparently broken, he is now one of them. Number Six and his minder climb into a Mini Moke taxi as triumphant martial music is heard over the Village speakers. Villagers line the entire route back to Number Six’s cottage, waving and cheering.

The remainder of the episode can be briefly summarized. (For those wishing to avoid spoilers, skip to the paragraph that ends “FADE OUT” and continue reading.)

Eighty-Six encourages our hero to lie down and relax while she makes him a cup of tea. When he sees her drop a pill into the drink, he pours it out as soon as her back is turned. After Eighty-Six leaves, Number Two arrives and, in an amusing scene, tries to coax Number Six into revealing why he resigned from his job. At this point, the audience is fully aware that no actual lobotomy has been performed on Number Six, and that the whole thing is a ploy to get him to give up his big secret. As noted earlier, Number Six suspects that this is the case, but he cannot be sure. The psychological technique used against him here is somewhat improbable. He is being tranquilized to create the impression that he has lost his aggressive tendencies, but would this really cause him to simply surrender all resistance and give the Village what it wants?

After Number Two leaves the cottage, promising to return later to continue their chat, Number Six removes the Band-Aid from his temple and discovers that he actually does have a scar. In the Green Dome, we see both Two and Eighty-Six observing him over closed-circuit TV as he roams through the cottage, pounding the surfaces in an attempt to confirm that he is still capable of aggression. Eighty-Six finds it curious that Number Six already suspects that he is being tricked, and, in the course of her conversation with Number Two, she reveals that the lobotomy procedure was indeed faked. On Two’s orders, Eighty-Six then returns to Number Six to administer another dose of the drug (referred to as “Mytol” in the episode, it appears to be fictitious[7]). She makes tea for both of them, dropping a tablet into Number Six’s cup. When she looks away, however, he switches the cups. A few minutes after drinking the tea, Eighty-Six is as high as a kite.

Number Six then goes out on his own, still confused and trying to sort the situation out. He ventures into the woods, to his old training grounds, and encounters the two thugs introduced in the very first scene. Believing him now to be docile, they begin pushing Number Six around. At first he is unsure of himself, still full of doubts about whether he really has changed. Soon, however, he recovers his fighting spirit and beats the stuffing out of both of them. Encountering the still very high Eighty-Six wandering the forest, Number Six hypnotizes her and compels her to reveal to him the entire scheme. Then, he gives her a posthypnotic suggestion — but we are left in suspense as to just what it is, for the scene then changes.

Number Six drops by the Green Dome and tells Number Two that he would like to address the entire Village to say how grateful he is to have received social conversion at last. Obviously he is up to something, but Two is entirely taken in. The zombified inhabitants are ordered to gather at the Village square, where Number Six addresses them, Two standing at his side. As he speaks, Number Eighty-Six suddenly steps into the square, shouting, “Number Two is unmutual! Unmutual! Social conversion for Number Two!” Number Six then makes a halfhearted attempt to inspire the prisoners to rebel, but they are not listening to him. They pursue an increasingly alarmed Number Two through the Village, chanting “Un-mutual! Un-mutual!” On reaching the steps to the Green Dome, he panics and begins running while the crowd chases after him. In the lead are the Karens: Number Forty-Two and her dour friends.

Once more, the revolution eats its own. FADE OUT.

I have spent so much time on “A Change of Mind” because, of all the 17 Prisoner episodes, this is the one that now seems most relevant to the present day. And again, this is a development that I never saw coming. The villagers’ extreme, bovine conformity; their emotional fragility; their hysteria; and their intense hatred of non-conformists struck me as absurd when I saw the episode for the first time, 40 years ago. Now it seems like an accurate depiction of what appears to be about half of the population. Even the elements clearly intended as parody now seem like naturalism. I find myself saying this over and over to my close friends: You simply cannot parody the Left anymore. We are now basically living in “A Change of Mind.”

There are other episodes that contain elements which also seem particularly relevant today — but, once again, most of them involve parallels between the villagers and today’s NPCs. The colorful costumes worn by the villagers are an indication of their lack of personal dignity (the decline in standards of dress has been staggering in the last 50 years or so). They don’t mind looking ridiculous. And notice how much time they spend partying, playing, and parading around. Silence and stillness might lead to introspection. The next time you watch the series, take a good look at the villagers ‘ faces when they are at their revels: almost none of them are smiling (clearly a deliberate touch on McGoohan’s part).[8] They are, to say the very least, overly socialized and extremely deferential to authority: Note, for example, how they are trained to freeze when Rover appears. They spout memorized slogans. “A still tongue makes a happy life” is no more a ridiculous thing to say than “diversity is our strength.” Note also how several episodes feature villagers who are literally identical to one another. “Arrival” and “Free for All” contain notable examples of this.

“Free for All” is the episode in which Number Six runs for election, seeking to become the new Number Two. It may be my favorite episode of all, and still looks great. But nowadays it also plays like an allegory of the Trump presidency: An outsider, an anti-establishment candidate, runs for election. The establishment tries every trick to coopt him, and, to a great extent, succeeds. To everyone’s surprise, he wins. No one knows what to expect (note the worried looks of his supporters when the election result is announced). But the Village authorities make a show of handing over the reins of power to Number Six — and then they beat him senseless and deposit him back in his bed. The End.

“Dance of the Dead” is also a particular favorite of mine. It’s another episode in which women are prominently featured, and Mary Morris’ Number Two is the most sinister in the entire series. Despite the elements of “A Change of Mind” that are clearly parodies of Communism, the series is generally apolitical. Indeed, in my first article on The Prisoner (originally published in the first issue of Tyr), I argued that the series essentially adopts the Heideggerean critique of Left and Right as “metaphysically identical.” We see more Heidegger on display in “Dance of the Dead” (though it is almost certainly a case of great minds thinking alike). The episode ends with Number Six on the loose in the mysterious Town Hall. He enters an elegant room which prominently features a folding screen obscuring a desk. Could Number One be behind that screen? McGoohan sweeps it aside to reveal a telex machine busily spitting out paper. He then rips out the wiring, thoroughly disabling it. But, as Number Two cackles behind him, the machine mysteriously comes to life again and keeps typing.

This is an inspired symbolic representation of what Heidegger meant by modern “machination” (Machenschaft): the relentless requisitioning of all beings by a merciless system that exists solely to propagate itself, transforming all that exists into disposable, interchangeable commodities. Underneath the sheen of attractive consumer products and diversions, it is machination that rules modernity — just as beneath the Village’s bright colors and gay revelry it is an inhuman, stainless steel machine-world that runs all. For Heidegger, human beings imagine they are the authors of this machine-world, but they are actually in thrall to it — just as Number Two and the entire mysterious crew that runs the Village are servants of the machine, not its masters. In the service of this machine, the distinctions of “Left” and “Right” are hardly meaningful at all — and no one has the power to shut it off.

You can buy Collin Cleary’sWhat is a Rune? here

I could go on, but instead I will simply invite the reader to watch the series and judge for himself how its meaning has changed with the times. But be prepared: While The Prisoner is always extraordinarily polished, it is also a mixed bag. In addition to some real timeless (and timely) gems, there are likewise some clunkers: e.g., “Hammer into Anvil,” “It’s Your Funeral,” and “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling” (the latter, shot while McGoohan was away filming Ice Station Zebra, is just downright bad). And there are certain things The Prisoner gets wrong. People today aren’t living in a jolly, antiseptic, low-crime, brave new world with all necessities provided. They are living in The Camp of the Saints and having to work their asses off to enjoy a standard of living far inferior to what their grandparents could count on.

In the four decades since I first saw The Prisoner, it has never been out of my thoughts for very long. I saw it when I was quite young, and it exercised a formative influence on me. So far as I can recall, it was The Prisoner that first awakened my mind to philosophy. It made me think, in other words. It led me to read authors like Kafka, Orwell, and Vonnegut. I write about it partly because I think I owe Patrick McGoohan something. That the figure of Number Six has been a role model to me for most of my life is something I discover anew each time I revisit the series. My misanthropy, my disdain for conformism, the pleasure I experience in flouting convention and violating rules — all of this comes from Number Six. I felt very much like him two years ago when I was living in New York City at the height of the Covid madness. For a time, we were ordered to wear a mask when outdoors. Feeling very McGoohanish, I took pleasure in roaming the streets maskless, like Number Six stalking around the Village without a badge, refusing to answer to his number.

If you have never seen The Prisoner, you need to start watching now (for the moment, every episode is free and in high-def on YouTube). If you have seen it before, see it again.

Be seeing you.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] Significantly, neither term is used in “A Change of Mind.”

[2] He is played by actor Michael Billington, in an early bit role. A few years later Billington would co-star in another ITC series, UFO. He also has the distinction of being tested for the role of James Bond more than any other actor. Though he never got the part, he did appear in a small role at the beginning of 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me as Anya’s doomed lover, Sergei.

[3] There are similar scenes in other episodes, notably in “Arrival.”

[4] However, it is established in an early episode (“Free for All”) that no real alcohol is available to the villagers.

[5] In the original script, Number Six has a violent altercation with some of the villagers after the episode in the café. That this scene may have been filmed and subsequently cut is suggested by the fact that when McGoohan returns to his cottage, his hair is disheveled, whereas in the café scene it is neatly combed.

[6] It should be noted that while individual psychiatrists and psychologists, and some professional groups, have declared racism to be a mental illness, efforts to include it in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) have not succeeded — so far.

[7] Though the writer may have in mind a barbiturate, Amytal.

[8] The extras who played the villagers were largely drawn from the local population living in the vicinity of Portmeirion, Wales.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 1: Nowa Prawica przeciw Starej Prawicy

-

Ignorance, Its Uses and Nurture

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

Slavery and the Weak Claim Paradox

-

Communist Barbarism in Hungary — and America Today: When Israel Is King

-

A Forgotten Treasure from the 1970s: The Star Wars Holiday Special, Part 2

3 comments

Thank you again for another fine essay about The Prisoner. One of the first essays I ever read here at Counter Currents was your first review of the series. It wasn’t so easily accessible at the time, but I’ll be sure to revisit now that it is.

Thank you very much!

You can also watch it here: https://www.shoutfactorytv.com/series/the-prisoner

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.