Eight Years & the Pain of Being Black in America

Morris van de Camp 2,085 words

2,085 words

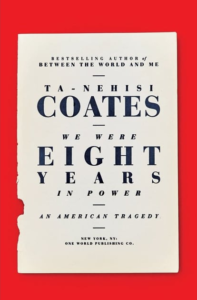

Ta-Nehisi Coates

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy

New York: One World Publishing, 2017

I expected to hate We Were Eight Years in Power. After all, the book is written by a guy with one of those, dare I say, unusual black names — Ta-Nehisi — and I’m a total white nationalist. But I ended up finding the book both interesting and wise. Ta-Nehisi Coates well expresses the pain of being black in America. Since Coates’ pain is driving local policy of removing white cultural items from coast to coast, one better take the guy seriously.

The book isn’t about the Obama presidency and its impact on America. Instead, it is a study of Coates’ pain of being black in America next to what Obama was doing at the time in a series of long-form essays. I’ve got a rough overview of the Obama administration below.

Coates starts his book with the three schools of thought that politically aware blacks have on how to relate to the wider white world. These schools of thought are best expressed with the names of the Africans that endorsed each one.

- Marcus Garvey: Endorsed a return to Africa and wished for blacks to do well as blacks. After a Jewish led show-trial, he was unjustly convicted of a “financial crime” and deported to Jamaica.

- Booker T. Washington: Believed that blacks should uplift themselves with thrift, hard work, etc. in a segregated environment.

- W. E. B Du Bois: Believed in “civil rights” as it exists now. He supported Communist-style wealth grabs against whites. He hated the white working class. Du Bois moved to Africa at the end of his life and died there.

Coates shows that Michelle Obama’s family were so deeply ensconced in Chicago’s South Side sub-Saharan political elite that they rarely interacted with the wider white world. They were essentially socially conservative Booker T. Washington people that lived in an all-black ecosystem. He argues that when Michelle Obama said she didn’t really discover her blackness until she got to Princeton, it was because that was the first time she was out of the African-American cocoon of the South Side. She wasn’t radicalized by Leftist beatniks at the university in the way many whites interpreted her statement to mean.

Coates discusses the merits and shortcomings of the Booker T. Washington worldview in depth. He argues that Bill Cosby’s “Pound Cake Speech” (i.e. encouraging blacks to not sag their pants and speak clearly) was well received by the socially conservative black community, but hated by the politically active Leftist elite. However, Coates was frustrated by Obama’s use of similar themes at a Morehouse commencement address.

I understand his frustration. All young men need some version of a tough love “Pound Cake” speech. (Don’t be a jerk, dress well, work hard, etc.), but at some point, one is doing all the right tough love stuff, and one must get advice on how to deal with more advanced problems — and a college commencement address is just the time to do that. I got my definitive tough-love experience(s) around age 14, and then had further tough love experiences until I was 19 working on the high prairie of North America. Then I discovered around age 23 that my next problem was deciding when to fire someone, and it only got more complex from there.

In other words, Coates is correct. It might have been wiser for Obama to give a speech on a larger ethical principle at Morehouse than “pull your pants up.”

Coates is also interested in the Civil War. He approaches the conflict from the viewpoint of a descendant of black slaves. Coates downplays the interpretation of the event as a failure to compromise, or some kind of big tragedy, that is put forward in historical works like Ken Burns’s Civil War. Instead, he views the conflict as primarily the result of slavery. From his viewpoint, blacks should be as engaged with the history of the Civil War as whites. They were the war’s ultimate winners.

I agree with this assessment. The Civil War was primarily caused by slavery — or better said — how slavery would expand, and Africans were the winners. All the other problems between the North and South were secondary. What made slavery so explosive is that Southerners understood African limitations while Northern abolitionists did not. I think one point Coates brings up is worth repeating:

The celebrated Civil War historian Bruce Catton. . . refers to the war as “a consuming tragedy so costly that generations would pass before people could begin to say whether what it had bought was worth the price.” All of those “people” are white (p. 77).

I don’t believe what was gained by the Civil War will ever be worth the price. While there is a real pain of being black in America, there is the pain of blacks being in America upon everyone else, and the Civil War was part of that pain and the war made the condition worse.

There is a great deal of discussion about mass incarceration. Coates believes that mass incarceration is due to simple racism. He argues that the crime wave of the 1960s through 1990s was global, to include a crime wave in the Nordic countries. There might have been a rise and fall in crime in Sweden at the time, but Swedes weren’t committing crimes at the scope and scale of blacks. Stockholm also didn’t go to rack and ruin like every city in the path of the black migration. Denmark didn’t have a crack epidemic or drive-by shootings. If you wish to have a society with the fraud of “civil rights,” then you must have big prisons for blacks.

There is a long essay about reparations for slavery. I won’t go into it, but I’ll mention that the problems arising from such a payout are easy to see, and those problems would likely play out like the bloody end of the 1919 Versailles Treaty or the Baron’s Revolt against King John in England.

Coates believes blacks are plundered by whites in America. This might have been true when slavery was around, but it is not true since slavery’s end. Blacks are a financial burden for whites.

You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here.

Obama’s Eight Years, Part I: Race

As mentioned above, the book isn’t about Obama as much as Coates expressing the pain of being black in America. While the book has a great deal of wisdom and insight, and I enjoyed reading what Coates had to say, I must indulge in a cheap shot mentioned by many others: All black intellectual endeavor ends up being about nothing but blackness itself, and this book is no different.

Meanwhile, Obama was in power for eight years and his presidency should be discussed.

Obama became president due to factors outside himself and within himself. Outside himself, Obama had the following advantages:

- The Republican Party had squandered decades of hard work, good government, organizing, and metapolitical effort on the disastrous Iraq War and the bumbling and stumbling George W. “Stupid” Bush.

- The Bush administration doubled down on an existing and dubious mortgage policy that blew the economy up in 2008.

- The GOP candidate, John McCain, endorsed a cruel and reckless foreign policy and failed to support white interests.

Within himself, Obama was a non-white version of a hero in a James A. Michener novel, but he came from the Pacific Islands to North America, rather than the opposite way Michener described in his books. Obama was mixed-race, lived in the Pacific, and went to a foreign people (South Side Chicago blacks) and intermarried with them, and then went to rule with liberal 1950s-style “civil rights” values.

Obama’s story was what many Americans craved. He was a blank screen for blacks and whites to project their fantasies upon. Additionally, throughout his career, people believed in Obama and saw something presidential in him.

Obama’s central accomplishment is being a better custodian of the United States than his predecessor. Otherwise, much of what he did was just poke along. However, he exacerbated divisions in the United States that are already unbridgeable and will likely lead to great instability and bloodshed in the future.

Obama’s negatives first became noticeable when he commented upon the arrest of Professor Henry Louis “Skip” Gates in 2009. Professor Gates was returning from vacation and had locked himself out of his house. He was spotted by a concerned citizen breaking into the property. The police were called, and Gates was arrested after making a scene.

While blacks (as a group) felt the police were in the wrong in that case, the affair really showed a lack of judgment on both Obama’s and Gates’ parts. Gates was a privileged, bookish professor who could have easily explained the situation to the beat cop and ended the problem in a minute. Obama’s comment on a local police matter made the incident a national racial firestorm.

Then Obama and his coalition — the media, black community organizers, et al — cynically made martyrs of two low-scale sub-Saharan criminals to turn out his base during election years. In 2012, the coalition’s hyping of Trayvon Martin helped get Obama re-elected, although the Republican challenger Mitt Romney had many, many, many negatives. In 2014, hyping the Michael Brown case eventually morphed into the Black Lives Matter movement in 2016. Black Lives Matter has since turned into a vast semi-terrorist network and left a trail of destruction wherever it’s been.

Coates is highly critical of the media’s handling of the Trayvon Martin affair in this book. His remarks on it are really wise and introspective and I felt his frustration. He’s a good writer.

Then there was the “Clock Boy” crisis. In 2015, Ahmed Mohamed, a Sudanese Muslim immigrant, was arrested for having what teachers thought was a bomb. Obama and his allies in the media turned the issue into a “teachable moment” on “Islamophobia.” However, it was discovered that Clock Boy had dissembled a clock to make it look like a bomb and was playing a carefully constructed prank.

I believe that Obama’s handling of the “Clock Boy” incident was a demonstration of a lack of judgment bigger than the Gates incident earlier. It is a well-known and standard policy for all government agencies to take bomb threats seriously. Furthermore, it was universally known that Islamic people have a propensity to bomb others. Obama’s handling of the matter signaled to actual Muslim terrorists an official stupidity. It turned out to be a green light for terror. Islamic terrorists plagued the United States and Europe thereafter until the new administration enacted a Muslim Travel Ban.

Obama never truly understood that nation that he ruled.

Part II: Foreign Policy

Obama did a passable job winding down the war in Iraq and he sent his elite sailors to slay Osama bin Laden in an event I still find glorious. But in other places, his foreign policy also poked along with no benefit to anybody.

In 2011, a civil war broke out in Syria. The cause of that conflict is beyond the scope of this article. The problem for the Americas was that Obama, acting in concert with his out-of-control and ambitious Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Israel-first Jews, and evil warmongers such as Senator John McCain, supported “moderate Syrian rebels.”

It quickly became clear that the “moderates” were not so different from the fanatics. The definitive history of this episode has not been written, and quite possibly will never be written, but it is not unreasonable to suppose that supporting a faction in the Syrian Civil War was done in part to secure Israel, and that support led to great evils such as the rise of the Islamic State. Obama also supported the overthrow of the Libyan dictator Gaddafi, which set off a chain of events that ended similarly poorly.

Obama also poured money into Ukraine to stoke a war there. As a result, Ukraine lost the territory that held a Russian-speaking population, including the vital Crimean Peninsula. I cannot explain or understand why Obama got involved in this region of the world other than to say he was unable to resist the pleadings of anti-Russian ethnonationalist Jews in the Democratic Party.

Suffice to say, American whites have responded to Obama’s eight years of weeping Negritude and crying deviants by electing Donald Trump as President, but the race problem remains. We have a choice. Build the white ethnostate, in part by encouraging blacks to follow the vision of Marcus Garvey, or we can submit to the endless emotional blackmail of the pain of being black in America.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Eight%20Years%20and%23038%3B%20the%20Pain%20of%20Being%20Black%20in%20America

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Get to Know Your Friendly Neighborhood Habsburg

-

Thank You, O. J. Simpson

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Police, in the Real World

-

The Worst Week Yet: April 7-13, 2024

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

9 comments

I must say, Mr. Coates is right. It is very tough being Black in the USA. We’re just awful, and they surely would be happier not being around us. I totally feel his pain. Let’s take up a collection and buy Mr. Coates a one-way ticket back to his ancestral homeland.

Mr. Coates wouldn’t like it and the real Africans wouldn’t like him either, unfortunately. He would catch the next available flight back to the U.S. in spite of any promises he made not to do that.

Thank you for doing the reading of the Coates book because there is no way I would ever do so.

I second the first comment. I am 100% in favor of free transportation back to Africa, where “dey can be kangz”, in exchange for renouncing their citizenship here in America.

I thank Morris de Camp for this review (and others). He makes a real contribution to CC and the White Cause in this way. But I have a suggestion for improvement which I hope he will consider in his career as a book reviewer.

When he makes a statement like this,

{Coates is highly critical of the media’s handling of the Trayvon Martin affair in this book. His remarks on it are really wise and introspective and I felt his frustration. He’s a good writer.}

it simply leaves the reader hanging. What are those “really wise and introspective” remarks? Frankly, I’m skeptical that Coates is capable of such (I’ve read a few of his essays, and mostly they were just long diatribes against whitey), so I would have appreciated Coates’s actual words, as opposed to de Camp’s assessment of them (which lacks any context for me to judge that assessment). Indeed, in the entire review, the writer is only allowed to speak for himself once (and most of the excerpted text was actually of a quote from Civil War historian Bruce Catton!). That’s not enough. That’s not how such reviews are normally (or optimally) done. There must be a balance between quoting the text under consideration, and analyzing it.

As for the actual book, what really motivated it was, I expect (from the plaintive tone of the title), anger that so little of the BLM-nationalist/supremacist agenda got legislated, despite “our” (our?) “8 years in power” (blacks are so racial nationalist; it never ceases to amaze even me …). Coates doubtless wanted Obama to be a hard-edged BLMist, really stickin’ it to “YT” with everything in the President’s Executive Branch arsenal, but instead Obama mostly governed as the opportunistic, Ivy League, progtard-left-liberal he truly is at heart. Obama will orate on white guilt themes to ‘up’ his ‘street cred’ with his black base, but he is basically neither a racist nor a communist (I believe this), but a Clinton/Pelosi/Biden standard left-liberal, with a bit more emphasis on multicultural “inclusivity”. That’s not nearly enough for Coates.

Of course Obama wasn’t a communist. Neither are the other Dems you mention.

I’m curious what your definition of “racist” is (there’s so many) and why Obama wasn’t/isn’t one. He most definitely viewed himself alienated early on from whites and stated so in his book, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance (1995). He discovered he had no common identity with, or interest in, Europe when he first traveled there. His identity was black and Muslim, which makes sense.

What made slavery so explosive is that Southerners understood African limitations while Northern abolitionists did not.

That may be true as a generalization, but there were some notable exceptions.

John Brown knew that blacks are less intelligent than whites, and he said so explicitly. Many of the white suffragettes who supported abolition, including Susan B. Anthony, knew that white women are smarter than black men. Elizabeth Cady Stanton worried that abolition and black suffrage would put women in the South at risk of “fearful outrages on womanhood” (i.e. rape). Predictably, her rational fear on this subject is now held against her.

Blacks and whites are both human, and if it’s wrong to enslave white humans, it should also be wrong to enslave black humans. From this humanitarian perspective, black limitations are irrelevant. That’s how many abolitionists reasoned about freeing the slaves.

Where a white voter lived must, of course, have affected his thoughts about abolition and black suffrage. If only one percent of the people in your immediate vicinity are black, you’re unlikely to see how the entry of black men into full citizenship could cause much trouble, even if you understand African limitations.

The celebrated Civil War historian Bruce Catton. . . refers to the war as “a consuming tragedy so costly that generations would pass before people could begin to say whether what it had bought was worth the price.” All of those “people” are white (p. 77).

These two lines give a nice summary of the black intellectual’s job, which is easy to do. You quote some distinguished white person, and then suggest that his whiteness somehow impugns whatever he wrote. Your black perspective on what a celebrated white historian wrote has a value in itself, since you’re black and he isn’t.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is saying here that not a single black person ever wondered whether the Civil War had been worth the price. We know, as a matter of fact, that many of them did, including former slaves. So a white critic of a black intellectual has an easy job too: he merely has to point out the black intellectual’s ridiculous factual errors.

Nice comments. Couldn’t agree more. Whites, in general, have a rather patronizing view of blacks, especially if they haven’t lived around large numbers of them. Plus, the human rights thing. Unfortunately, that god has morphed from the image of Thomas Jefferson into a beetle-faced, pregnant hermaphrodite.

Only returning freed blacks back to Africa after the War between the States ended would have made all that bloodshed worth the price.

OK, so Ta-Nehisi sees a black guy at the White House, and thinks “WE are in power now.”

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment