Imitation of Life & an Imitation of Imitation of Life

Travis LeBlancWe live an age where no one wants to be white if they can help it. That’s why you have honkies like Robert “Beto” O’Rourke pretending be Hispanic, Shaun King pretending to be black, and Elizabeth Warren pretending to be Native American. But it was not so long ago when the opposite was true, and it was non-whites who, if possible, tried to pass themselves off as whites. Imitation of Life is a movie about the latter.

Imitation of Life is about a mulatto girl who is struggling with her ethnic identity in the era of racial segregation. She’s light enough that she can pass for white, but her charcoal-black mother keeps showing up and blowing her cover, causing much resentment and conflict. There are other subplots as well, but the one about the mulatto daughter is the one everyone remembers.

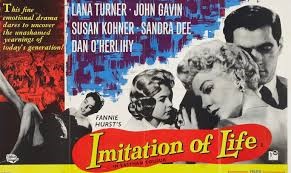

Imitation of Life was made twice: once in 1934 and again in 1959. They were produced in different eras of our racial history – and it shows. Despite having the same premise, they are very different movies and rely on different clichés and racial archetypes. In 1934, segregation was considered a simple fact of life, and people still saw nothing wrong with performing in blackface. As such, segregation is presented as morally neutral, and the black mother is portrayed as an innocent but simple-minded mammy type. Lots of “Yes’m,” “honey child,” and “I do declare.”

But in 1959, the Civil Rights battle was heating up and segregation’s legitimacy was being questioned by many. As a result, the 1959 version has a much stronger propaganda vibe to it and segregation is presented as indisputably malevolent, with the specter of white racism haunting it at every turn. Also, people had begun to turn against certain racial stereotypes, and so the black mother is portrayed as strong, wise, noble, and soulful. It’s every bit as much of a stereotype as “mammy” – and one that is still used today – but it is a positive stereotype.

You can watch the 1934 version here, and the 1959 version here.

Imitation of Life was originally a novel written by Frannie Hurst, a Jewess who specialized in novels about societal outsiders: immigrants, minorities, gays, and hookers with hearts of gold. That sort of thing. Hurst also never met a subversive movement that she didn’t like. She was a pioneering feminist, civil rights activist, and dabbled in Zionism later in life. She was also a Communist sympathizer (of course) and visited the Soviet Union in the early 1920s, where she was granted an audience with Leon Trotsky, who was apparently (along with Lenin) a big fan of her work.

Some suspension of disbelief is required when watching both movies, as there is a big strawman in both. In both movies, the black mother is far too dark to have a child as light-skinned as the one shown in the movie. Breeding with the palest Irish ginger would not produce a daughter as light-skinned as she is. And apparently, the mulatto girls’ father was not even white. In the 1934 version, he’s described as “high yella” (light-skinned black) and as “practically white” in the 1959 version. Thus, we’re expected to believe that this white-looking girl is the product of not one, but two blacks – or at least one jet-black and one mulatto. This girl just freakishly ended up as lighter-skinned than both her parents.

Some suspension of disbelief is required when watching both movies, as there is a big strawman in both. In both movies, the black mother is far too dark to have a child as light-skinned as the one shown in the movie. Breeding with the palest Irish ginger would not produce a daughter as light-skinned as she is. And apparently, the mulatto girls’ father was not even white. In the 1934 version, he’s described as “high yella” (light-skinned black) and as “practically white” in the 1959 version. Thus, we’re expected to believe that this white-looking girl is the product of not one, but two blacks – or at least one jet-black and one mulatto. This girl just freakishly ended up as lighter-skinned than both her parents.

Louise Beaver and Fredi Washington as Delilah and Peola Johnson in the 1934 version of Imitation of Life.

Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner as Annie and Sarah Jane Johnson in the 1959 version of Imitation of Life.

In the 1934 version, the young mulatto girl is played by Fredi Washington, the daughter of two mulattos. In reality, she was much darker than she appears, and heavy makeup was used to make her lighter – and presumably more relatable – to Depression-era white audiences.

Susan Kohner, who plays the mulatto in the 1959 version, was a Jewess without a drop of negro blood in her, and only a tiny sliver of POC. Kohner’s father was Paul Kohner, a Jewish movie producer active in the late silent and early talkie period, and her mother was Lupita Tovar, a Mexican-Irish actress most famous for appearing in the Spanish-language version of Dracula.[1] So Susan Kohner was only a quarter POC – and even that quarter is part white.

Hollywood is playing tricks on us here. The theme is still worth examining, but the scenarios presented are rather ridiculous. It doesn’t completely ruin the movies, but it is definitely distracting.

The 1934 version is apparently closer to the original novel (which I will confess to not having read). The premise goes something like this: Claudette Colbert plays Bea Pullman, a white widowed single mother from Atlantic City. One day she gets a knock on the door from Delilah Johnson, a black widowed single mother who has come to answer a job for a live-in maid. But Delilah, being incredibly dumb (that’s not me being racist; she is deliberately presented as naïve and childlike), has arrived at the wrong address. But Bea takes pity on Delilah and hires her as a live-in maid anyway, and the two women’s daughters, Jessie and Peola, become fast friends.

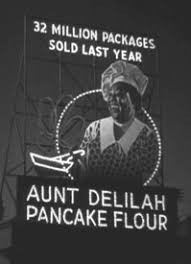

Shortly after moving in, the white mother learns that the black mother has an amazing pancake recipe, and so they start a pancake shop together. After a few years in business, a traveling salesman comes to the shop and persuades them to sell their pancake recipe by the box. He becomes their manager, arranges a deal with Megacorp to box the pancake mix, and the two become absurdly wealthy and move into a palatial mansion in New York City.

Shortly after moving in, the white mother learns that the black mother has an amazing pancake recipe, and so they start a pancake shop together. After a few years in business, a traveling salesman comes to the shop and persuades them to sell their pancake recipe by the box. He becomes their manager, arranges a deal with Megacorp to box the pancake mix, and the two become absurdly wealthy and move into a palatial mansion in New York City.

While the relationship between Bea and Delilah is one of mistress and maid, in practice it is something of a Boston marriage. Bea acts as the patriarch: She handles the business dealings and is the brains of the pancake operation, making sure the bills get paid on time, while Delilah acts as her assistant and takes care of Jessie and Peola, who are de facto stepsisters. In fact, even after they get rich, Delilah insists on continuing to live with Bea as her cook.

An ad for Imitation of Life from a black theater in Atlanta gives Louise Beavers and Fredi Washington top billing.

While all this is going on, things start getting rough for poor Peola. First, Jessie and Peola had a childish tiff in which Jessie calls Peola “black” as an insult. Peola is inconsolable, as up until then, she saw Jessie as her sister, but now Peola learns that Jessie sees her as an “other” – and a rather low-status one at that. “I’m not black! I won’t be black!” she cries.

Delilah seeks to comfort her by saying, “Now, now, now, Peola. Calm yourself, baby. You gotta learn to take it. You might just as well begin now.” Peola responds by blaming her mother for her situation “You! It’s ’cause you’re black. You made me black. I won’t! I won’t! I won’t be black!”

The other kids at school accept Peola as white, at least. That is until one rainy day when bubble-brained Delilah shows up at Peola’s school to give Peola her raincoat and rubber boots, not knowing that Peola had been successfully passing as white at school. But Delilah’s appearance blows Peola’s cover to her astonished class. One kid whispers “I didn’t know she was covered!”

The classroom scene is one of the few that is more or less the same in both versions, and if you want to understand the difference between the two films, it can be summed up by the difference in how the black mother responds to this scene. In the 1934 version, after returning home, Delilah feels regret, and says, “She was passin’, Miss Bea, and I give her away. She know I wouldn’t have done it on purpose.”

You have to wonder how Delilah could be so dumb as to not know – or to at least ask Peola if she didn’t. When Bea suggests sending Peola to a different school, Delilah responds, “I can’t keep sending her to different schools all her life, Miss Bea,” implying that similar situations have happened before.

In the 1959 version (we’re skipping ahead for a moment here), the wise and noble Annie Johnson blows her daughter’s cover and shows no remorse:

While the 1934 Delilah Johnson has some understanding as to why her daughter would want to pass as white, the 1959 Annie Johnson finds such a deception immoral. She says:

It’s a sin to be ashamed of what you are. It’s even worse to pretend, to lie. Sarah Jane has to learn that the Lord must have had his reasons for making some of us white and some of us black.

In the 1934 version, by the time Peloa is an adult, they are all fabulously wealthy and living in a mansion in New York. Bea has thrown a party full of wealthy New York socialites, which Delilah and Peola can only listen to from the basement. Peola is particularly irritated that she cannot join the party.

Peola: How long is this party gonna keep up, anyway?

Delilah: What’s the matter with my baby?

Peola: I’m sick and tired of it.

Delilah: What, the party?

Peola: No . . . not the party.

Delilah: What is it, baby? What’s my baby want?

Peola: I wanna be white like I look.

Delilah: Peola.

Peola: (looking into a mirror) Look at me. Am I not white? Isn’t that a white girl?

Delilah: Honey, we’s had this out so many times. Can’t you get it out of your head?

Peola: No, I can’t. You wouldn’t understand that, would you? Oh, what is there for me, anyway?

Bea and Delilah’s solution is to send Peola “”down South . . . to one of them high-toned colleges where only the high-toned goes.” Peola initially balks at going to “a negro school,” but eventually gets sent down there anyway. Shortly after arriving at the Southern negro college, Peola goes AWOL. Bea, being rich and resourceful, is able to track Peola down to a restaurant where she is passing for white and working under a fake name. When Delilah comes into the restaurant to bring her back, Peola pretends not to know her. Peola would rather be a white shop girl than the black daughter of a millionaire.

Peola eventually returns to New York, but only to tell her mother that she never wants to see her again. She wants to be white, can be white, and is tired of having her mom repeatedly blowing her cover. So she instructs her mother that should she ever see Peloa on the street, to pretend not to recognize her.

After this, Delilah become ill and finally dies with a picture of Peola at her bedside. It is implied that Delilah has died from the proverbial broken heart. Having been rejected by her only child, she loses the will to live.

However, Bea throws a lavish funeral for Delilah, and Peola returns and begins crying and wailing uncontrollably over her mother’s casket, saying “I killed you!” and “I killed my own mother! . . . She worked for me, slaved for me. Always thought of me first, never of herself.”

There is another subplot involving a love triangle between Bea, her scientist/socialite suitor Steven Archer (played by John Barrymore), and Bea’s now-teenaged daughter Jessie. Archer and Bea are planning to marry when they learn that Jessie has a huge crush on Archer, and so Bea has to call things off so as to not strain her relationship with her daughter. It’s not nearly as compelling as the subplot regarding Delilah and Peola.

The 1959 remake is a mixed bag. On one hand, it comes off as a little too Hollywood. It replaces the pre-code grit with the 1950s gloss of the studio system at the height of its powers. The characters are a little too glamorous and too good-looking, with some trashy, Valley of the Dolls-style unintentional camp. You are very aware that you are watching a big-budget Hollywood movie, which takes something away from the immersive experience. That said, the characters here are a bit more complex and there is some snappy dialogue. It’s a better-written movie despite taking its creative liberties.

A curious aspect of it is that it is a much more gentile-centered affair despite being more anti-white. The 1934 version was produced and directed by (((Carl Laemmle, Jr.))) and (((John M. Stahl))), while the 1959 version was produced by (((Ross Hunter))). It was directed by Douglas Sirk, who was of Danish parentage, and the screenwriters were Eleanore Griffin and Allan Scott, who were both of Irish stock.

The 1959 version also changes the plot in some significant ways. Instead of getting rich by starting a pancake shop with her black maid, in this version, the white widow (played by Lana Turner), who is at first a struggling out-of-work actress, becomes a wildly successful Broadway star. This change was probably made to accommodate the star Lana Turner, a very glamorous woman of limited acting range. You can’t make a movie with Lana Turner in it and not have her wearing extravagant gowns, and no one is going to believe Lana Turner as some genius businesswoman who starts a pancake empire.

And in this version, the two mothers start out already living in New York, and meet by chance on a Coney Island beach after their two daughters (in this version named Susie and Sarah Jane) start playing with each other. One thing leads to another, and this broke, out-of-work actress lets this strange black woman and her child move in with her. It doesn’t make a lot of sense, but whatever – it’s just a movie.

These alterations change the dynamics a great deal. Instead of the two mothers becoming successful together, here the white mother achieves fame and wealth alone, while the black mother remains a simple maid. Despite the fact that she goes from being a low-status maid to an unemployed actress to a high-status maid to a celebrity actress is definitely an upgrade, the fact is that she’s still a simple housekeeper. This makes the mulatto girl’s running away more understandable because she’s not leaving as much behind, as in the 1934 version.

The Broadway subplot introduces the character of Allen Loomis, the unapologetically sleazy Broadway agent played by Robert Alda (Alan Alda’s father), who has some of the best dialogue in the movie, such as, “I haven’t been seen with a girl without a mink since the heat wave of 1939.” After Lana Turner rejects one of his advances, he says, “Oh, and you’re decent, too. No doubt possess some fine principles. Well, me, I’m a man of very few principles, and they’re all open to revision.” Later, he says “I, for one, can’t keep my beady eyes open.” Is this his way of telling us he’s Jewish?

The characters are also altered a bit. The black mother is made more sympathetic by being smarter and “black and proud,” while the mulatto daughter is made less sympathetic. She’s still obsessed with being white, but she’s made out to be kind of a stuck-up bitch. She not only longs to be white but frequently expresses contempt for blacks and her belief that she is better than them. When her mother asks Sarah Jane why she doesn’t find herself a nice black fellow, she derisively replies, “Busboys, cooks, chauffeurs!” She feels she deserves better. I can’t blame her. Sarah Jane is attractive enough to get a high status white, so why should she settle for less? She’s just being a bitch about it.

In the same scene, after being asked to accept her black heritage, Sarah Jane does so by carrying a dinner tray to the party guest on her head, and does an imitation of a stereotypical black: “Fetched y’all a mess of crawdads, Miss Lora, for you and yo’ friends.“ A dinner guest replies, “That’s quite a trick, Sarah Jane. Where did you learn it?” To which Sarah Jane responds, “Oh, no trick to totin’, Miss Lora. I learned it from my mammy, and she learned it from old massa ‘fore she belonged to you.”

Ironically, Sarah Jane’s “racist” negro impression sounds a lot like Delilah in the 1934 version. In fact, the line is vaguely similar to a line in it in which Delilah says, “Them pancakes is my grannie’s secret. She passed it down to my mammy, and my mammy told me.” But it shows that in the twenty-five years since the original, the old mammy archetype that Delilah was based on had become offensive.

White racism, which is all but absent in the 1934 version, is always looming in the 1959 one. At the beginning, Annie Johnson mentions, “Miss Lora, we just come from a place where, where my color deviled my baby” – meaning that the whole reason they ended up in New York was to escape bad, white racism.

There’s another early scene when Lana Turner discovers that Susie has cut her arm to prove her classmates wrong after they said that negro blood is different from white blood, by showing that indeed, “we all bleed red.” No doubt those kids also believe that chocolate milk comes from chocolate cows.

Sarah Jane is not just after the social rewards of being white, but also seeking to avoid the social penalties inflicted on blacks by sadistic white racists.

Sarah Jane elaborates on her feelings about race and her racial identity in a conversation with Susie. Susie has just caught Sarah Jane sneaking back into the house and asks her where she has been.

Sarah Jane: I’ve been out. With my boyfriend.

Susie: Boyfriend? I didn’t know you had a boyfriend! Where’s he from?

Sarah Jane: The Village.

Susie: Oh. Did you meet him in school?

Sarah Jane: School? No. There’s an ice cream parlor in The Village with a jukebox.

Susie: Yeah?

Sarah Jane: And he used to stand outside, and every time I’d walk by, he’d whistle! No kidding! But first I pretended he wasn’t on Earth.

Susie: Yeah?

Sarah Jane: But finally I had to laugh, and he followed me. And we started to talk. He’s cute. Really cute.

Susie: Is he a colored boy?

Sarah Jane: (offended) Why did you ask that?

Susie: Well, I don’t know. It just slipped out.

Sarah Jane: It was the first thing you thought of.

Susie: I told you, it just slipped out!

Sarah Jane: Well, he’s white. And if he ever finds out about me, I’ll kill myself.

Susie: But why?

Sarah Jane: Because I’m white, too. And if I have to be colored, then I want to die.

Susie: What are you saying?

Sarah Jane: I wanna have a chance in life. I don’t wanna have to come through back doors, feel lower than other people, or apologize for my mother’s color.

Susie: Don’t say that!

Sarah Jane: She can’t help her color, but I can. And I will.

Susie: But we’ve always talked things over. You never told me this before.

Sarah Jane: Because I’ve never had a boyfriend before. Because he wants to marry me someday. A white boy. Me. But how do you think he’d feel, or his folks, with a black in-law. What do you think people would say where we lived if they knew my mother . . . They’d spit at me. And my children.

Susie: Sarah Jane, you know that’s not true!

Sarah Jane: It is. That’s why he mustn’t know her. I don’t want anybody to know her.

Susie: What if he comes here?

Sarah Jane: He doesn’t even know where I live. I pretend I’m a . . . I’m a rich girl with strict parents.

Susie: Well, he’s bound to find out . . .

Sarah Jane: How? I’m going to be everything he thinks I am. I look it, and that’s all that matters.

Unfortunately for Sarah Jane, her boyfriend finds out about her racial identity, and the next time they meet, he beats her up to the sound of hot jazz music.

The music in that scene is what I’m talking about when I referred to “unintentional camp.” Whatever emotional impact it could have had is undermined by the musical selection.

Sarah Jane’s first attempt at living a white girl’s life fails because her boyfriend finds out about her mom. She then makes another go at it. She tells her mother that she got a job at a library, when in reality, she got hired as a dancer in a shady burlesque club. Sarah Jane would rather be a white stripper than the black daughter of a high-status maid. Her mother tracks her down to the club and threatens to call the police if they don’t fire her (she is presumably underage).

Sarah Jane is furious with her mother, who has ruined her white alter ego once again. She runs away from home. Lana Turner hires a private investigator, who manages to find Sarah Jane working as a showgirl in Hollywood. Unlike in the 1934 version, where Peola just wants to be a normal white girl, the 1959 Sarah Jane is willing to be a trashy white girl if it means she can also be white. It presented her quest to be white as leading her down a dark path.

Annie Johnson goes to Hollywood and meets with her daughter one last time – not to bring her back, but to say goodbye. She finally accepts that living as a white girl is the only thing that will make her daughter happy, and tells Sarah Jane that she does not intend to interfere with her life any longer. Letting go is Annie’s final, ultimate act of love for her daughter.

In the 1934 version, Delilah understood her daughter’s drive to be white, but never quite fully accepted it. Later, when Annie becomes ill and is on her deathbed, she makes a last request to Lana Turner: “Miss Lora, just tell her . . . Tell her I know I was selfish, and if I loved her too much, I’m sorry. But I didn’t mean to cause her any trouble. She was all I had. Tell her, Miss Lora.”

From then, the movie plays out in the same way as the original: The black lady dies of a broken heart and her daughter shows up at her funeral, sobbing uncontrollably and realizing only too late what her mother meant to her.

As anti-segregation propaganda, both movies fail, but it does make you wonder if Single Drop laws were perhaps a tad excessive. Even though they were conceived as Leftist propaganda, I still find them to be interesting meditations on what it means to be white. I have no intention of accepting black mothers into my ingroup, but what about the Peolas and Sarah Janes? Are they white? What is white, anyway?

My stock answer to “Who is white?” is that there are three components to identity:

- Does the person see him- or herself as being part of Group X?

- Do other people in Group X see that person as being part of their group?

- Do people outside of Group X see that person as belonging to Group X?

If someone meets all three conditions, it’s really irrelevant if someone has twelve percent Cherokee ancestry. Jews are not white because while they may meet the second and third criteria, most of the time (even j-woke minorities see Jews as a kind of white person) Jews do not meet the first condition: They do not see themselves as white. Is that standard perfect? Of course not. But it’s an adequate rule of thumb when dealing with most edge cases.

By that standard, I would be inclined to accept Peola and Sarah Jane into my ingroup (but not the actresses who played them, who are indisputably non-white). The 1959 version Sarah Jane was very explicit that she did not merely look white, but that she was white. (“Jesus was white. Like me.”)

But then again, I am writing this in 2019, when whites are an endangered species. When the revolution comes, we’re going to need everyone we can get, and frankly, it’s refreshing to see someone like Sarah Jane, who is not only proud of her whiteness but in fact quite enthusiastic about it. I hate to be one of those “I’d rather live next door to Thomas Sowell . . .” types, but yeah, I’d rather have Sarah Jane Johnson on my side, as a highly ethnocentric slightly off-white, than Justin Trudeau.

Note

[1] Hollywood briefly experimented with filming Spanish- and English-language versions of movies simultaneously, producing the English version in the day and the Spanish version at night using the same sets and costumes. Tovar began as part of Universal’s Spanish team, but was later “promoted” to doing English-language movies.

Imitation%20of%20Life%20and%23038%3B%20an%20Imitation%20of%20Imitation%20of%20Life

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Will There Be an Optics War II?

-

Thank You, O. J. Simpson

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

Civil War

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

The Holocaust Card Can No Longer Be Played

-

Problém pozérů aneb nešíří se snad myšlenky pravicového disentu až příliš rychle?

15 comments

I thoroughly enjoyed your review but you left out the cringe elements in this movie. One example, the screaming crying when the Black mom dies, I feel cringe.

This is a wonderful comparative analysis of both movies. The writer mentions that Lana Turner had limited acting skills. Quite so, and the same can be said of the actress who played her grown daughter Susie in the 1959 film — Sandra Dee.

A book by Cid Ricketts Sumner, “But the Morning Will Come”, will curl your toes. Here is an amateur’s review of it:

I almost always finish a book that I start, but this is an exception. The novel, published in 1949, concerns a young woman married to a moody older man living on a Mississippi plantation. She is pregnant and 1/3 of the way through, she discovers that her husband is moody because he is hiding the fact that he has black blood in his ancestry. She is shocked and appalled and I instantly began to scan forward to see if this attitude ever changed. It didn’t and the title apparently reflects her agonized resolution to go on with her life.

I am also shocked and appalled, to find this attitude still reflected as late as 1949. So, unless you are a Klan member or an ignorant redneck, avoid this racist garbage…and that’s where I promptly threw this depressing book!

I read this book when I was in my 20s and it went right over my head. Sumner was quite the liberal, writing other books on the evils of segregation and all that. She was beaten to death by a relative, so not everyone was taken with her fine character.

Both movies sound like the beginning of the ‘sob story’ industry from Hollywood, which makes us feel unrealistic sympathy for impossible situations. These sob stories are especially prevalent today, and they are the cornerstone of Leftist propaganda to make us ‘poor, mean white people’ feel bad about ourselves. When I was young, I used to fall for this stuff and cry my eyes out (which was the intent) but now I am ‘on to’ the intent, and just ignore the emotional tangles. My friends still tell me I have no heart, but I won’t allow my psyche to be manipulated by these immensely sad stories. Nor by horror movies, for that matter.

Most on the point comment. These movies are needlessly manipulative and at best a waste of time because the premise is practically impossible. Anyone who can actually pass as depicted here has no such existential identity crisis because they would have been born of one white or white passing parent and another who has a foot in both worlds but leans white. I have known a few of these people. You’d never know they were black and they’re not looking for your sympathy.

Loved the punch line at the close!

As a sometime Counter-Currents reader, I felt the need to comment for the first time. It was due to the poignant line regarding the 1934 version of Imitation of Life. “Peola would rather be a white shop girl than the black daughter of a millionaire.” This harkens back to the NY Times mulatto reporter who came from New Orleans and hid his real identity from his own children for most of their lives. If you want to see an idealized version of a mulatto adult, Lolo Jones, the Olympic Hurdler some years back comes to mind. Or the actress Stacy Dash. But definitely not Sandra Dee.

But do let that line sink in carefully, about wanting to be part of the white world even if its not very glamorous or wealthy. And remember, this was made at the height of the Depression. In other words, the not so subtle message is that poverty isn’t pretty, but there are some things even worse than poverty, and that’s not having any standards. Better to have self worth and dignity, and if that means giving up riches, so be it.

THAT is the worldview of the first half of 20th century America, and most whites (as well as most blacks) would’ve not only understood the sentiment behind the line but viscerally agreed with it as well. Translation: Even the lowest rung on the white totem pole takes precedence over the highest level of being black.

Also, in its own way, the 1934 version is more realistic regarding race relations between blacks and whites on a day to day fashion. It’s subtle, but its real nevertheless. Even the mulatto actress playing the black mammy’s daughter is a much more realistic looking version of what an offspring from such unions would have been like, and certainly if she hadn’t been whitefaced up for mainstream audiences during the Depression. In the 1934 version, most US blacks were employed as maids, cooks, etc. they weren’t rich. Therefore Louise Beavers portrayal was realistic of the type of role of ordinary black women. The 1959 version, however, the portrayal was more embarrassing, because while still technically accurate that she was a maid, she can’t be shown as becoming rich as a famous cook, because that’d be racist. It’s almost as if the screenwriters have to apologize that they couldn’t figure out a way to make the black woman rich in her own right without help from whitey, as that template didn’t yet exist (the way it would today, like making her an Oprah figure).

But as far as reality goes, the 1934 version is more realistic portrayal of race relations in the US on a daily basis. Since intermixing wasn’t anywhere near as widespread as it is today, one could be more frank about certain things that both sides had to deal with without laboring on it. By 1959, however, most of the frankness was characterized as racist and so they couldn’t be up front and honest about how life was for mulattoes (at that time was still rare in the US).

But either way, the line sums it all up: Better to be poor (during the Depression no less) and at least pass for white, rather than be rich and black.

‘but not the actresses who played them, who are indisputably non-white). ‘

What does this mean?

The actresses are less white than the characters they played. Fredi Washington was much blacker in real life than she appears in the film and Susan Kohner, while not a POC per se, is half Jewish which is not white.

One was 1/2 black, made to look Whiter than really was and identified as black, the other was of Mexican and Jewish decent, though based on authors criteria for who is White (colour and identification), is he assuming she identified as something other than White?

Odd you had to ruin review with dubious racial views, based on something as superficial as colour and social advantageous attached identification…theoretically speaking with the rise of White racial consciousness and power, where it become disadvantageous for Jews to be openly Jewish, they can just identify as White and all’s fine? Also any mulatto and other mixed person can then just choose to be “White” so long as light enough.

A great contribution from Travis. There is the suggestion that Susan Kohner has a sliver of POC. This does not appear to be the case. Nothing in her mother’s appearance suggests any mestizo strain. (Lupita Tovar’s family were in Oaxaca, and as white Europeans would have moved within their own circles down there.) Susan’s father was of course Jewish, as was her husband, the somewhat famous German-Jewish-British-American menswear designer and wartime OSS operative, John Weitz.

The movies sound interesting, analysis of the times in question are also good, but however I must strongly disagree with some of the conclusions in the review.

“We live an age where no one wants to be white”-WRONG. The majority of the world (and that majority is non white) would do anything to be white. I am sure those of you with asian wifes can attest of this by looking how many of different whitening products she has (to simplify probably all her products are whitening).

Skin lightening products make up HALF of world’s entire cosmetics industry.

https://www.marketwatch.com/press-release/skin-lightening-products-market-is-expected-to-reach-a-valuation-of-over-us-24-bn-by-the-end-of-2027-2018-08-30

Or the said colored world will desperately try to improve their genes my mixing with whites, therefore so many whites with low self esteem end up race mixing (it’s ultra easy, the effort required is minus). And because of that there are trends like these:

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/3dx9nj/women-are-now-pillaging-sperm-banks-for-viking-babies

https://www.thecoli.com/threads/demand-for-american-sperm-is-skyrocketing-in-brazil.618540/

Regardless what you THINK objective reality still exists. Non-White is still non-White, no matter how he or the whole world sees him or her. Race mixing is not ok regardless of mental gymnastics. Ah… and once we were known for having standards, now basic things seen to be not clear for some.

In my opinion, that the goal of the current culture and of certain people, is not to remove all “Caucasians”. But to get all White people to look according the name. I will explain here: yes in USA the meaning Caucasian is interchangeable with White, but people who in practice live in Caucasus region are mostly non white, they are ethnic in the truest sense of it, when I hear Caucasian – in my minds eye I see this: https://duckduckgo.com/?q=ajerbaijan+traditional+clothes&atb=v98-1&iar=images&iax=images&ia=images Therefore the name “Caucasian” was chosen in the first place. Caucasian yes, but not pure white at all. This is where we will quickly end up with with the mindset like in this review.

I’m a little bit surprised that the 1959 version didn’t co-star popular singer and sometime actress Lena Horne (who was definitely high yella, a well known mulatto). If there was one famous pop culture woman in the pre-1960’s segregation era, it was her. It would also have made sense that she could be a Broadway star just as Lana Turner, that way both actresses could get rich together and continue the same theme from the 1934 version. Remove the maid occupation since by the late ’50’s that was causing some difficulties with the Left.

Not that it would be believable that she would’ve had as white looking a daughter, but it would’ve been significantly more plausible, especially to the overall plot. Ironically, the 1959 version, for all its attempts to be culturally relevant, hip to the times regarding Civil Rights, etc., the thing that comes across is that its apparent that the screenwriters had little direct contact with blacks in their daily lives (unless they were wealthy enough to have employed nannies/maids), and thus just assumed that blacks were simply whites covered with dark paint or something. Again, as far as race relations go, the 1934 version was more realistic in a subtle way. Louise Beavers, the actress who played Delilah, made a career out of playing the same role for several decades. When asked why she played maids all the time, she supposedly quipped “better to play one on the screen than to be one in real life.” But still, at least the 1934 version is showing a realistic portrayal of how blacks acted in daily life. Similar to blacks today speaking ebonics (e.g. Rachel Jeantel). What’s the difference? None, actually.

“By that standard, I would be inclined to accept Peola and Sarah Jane into my ingroup (but not the actresses who played them, who are indisputably non-white).”

Why? Susan Kohner could easily fit all there criteria.

Both movies’ premises are absurd. No child of a really black mother could ever look like Susan Kohner.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment