Why The Birth of a Nation Is the Most Important Film of All Time

Travis LeBlancThe first match was struck by Griffith, and it led to an explosion, the effects of which the industry is still feeling. The Birth of a Nation was a cinematic revolution — it was responsible for revolutions in every field affected by motion pictures. Riots and demonstrations were living proof of the power of the film. No well-informed person could allow themselves to ignore it. The intelligentsia, who had regarded movies much as the jukebox is regarded today, conceded at last that the film had value. With critics and writers embroiled in controversy, the middle classes went to see for themselves. And more important still, the men who controlled the business grew ambitious again. — Kevin Brownlow, The Parade’s Gone By

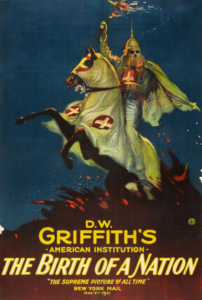

The Birth of a Nation is a movie that everyone has heard of but few people have ever actually watched. Liberals love to tell the story about how once upon a time, there was an outrageously popular movie in which the Ku Klux Klan were the good guys, and white people across the country had cheered as the Klan lynched blacks, who were portrayed as sex-crazed monster with an insatiable appetite for white women. Worse yet is that the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, had it shown at the White House and said complimentary things about it. The Birth of a Nation, they say, was so popular and irredeemably racist was that there was a notable uptick in lynchings following its release, and that it inspired the Klan’s rebirth. The Birth of a Nation, they claim, is irrefutable proof of just how racist the United States was only a century ago.

Everyone focuses on how racist The Birth of a Nation was. What is less discussed is how monumentally important it was for the craft of filmmaking and for the film industry. It is hands down the most important film ever made. It changed everything. Indeed, the fact that the film capital of the world is located in Hollywood is because of The Birth of a Nation. In 1915, when the film was released, America’s film capital was in Fort Lee, New Jersey, while Chicago was trying to set up its own rival film industry. The fact that The Birth of a Nation was made in Hollywood and went on to be so successful persuaded the Fort Lee studios to close down and move out West. (Granted, the Spanish flu outbreak of 1918 was also a factor.)

Here are some reasons why The Birth of a Nation is the most important movie of all time.

Incredible profits

No one knows how much money The Birth of a Nation made, only that it was an astronomical sum far in excess of any film that had come before it. People who were around at the time testified that it was a movie that “everyone saw”. There are some who theorize that The Birth of a Nation might in fact still be the highest-grossing movie of all time when adjusted for inflation. A 2015 Time magazine article on the film’s centenary estimated it to be in third place, behind only Avatar and Titanic.

The reason we don’t know how much money it made is due to how film distribution worked in the 1910s. Film studios would sell copies of the film to theaters, after which the theater owner could do whatever he wanted with it. This changed in the 1920s, when the practice became for a studio to lease a copy of a film to a theater, after which it was sent back and the two parties would split the profits. This is besides the fact that there were many pirated copies of The Birth of a Nation playing across the country; we definitely don’t have any solid numbers regarding those.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here

But there are some things that we do know. We know that The Birth of a Nation was very expensive to see: $2.20 per ticket, at a time when the average person made 33 cents an hour. Most movie tickets sold for ten cents, but The Birth of a Nation cost the same as a Broadway show.

We also know that The Birth of a Nation made a lot of people a lot of money. Most of the major studios of Hollywood’s Golden Age can in some way trace their history back to The Birth of a Nation. The film’s director and co-producer, D. W. Griffith, went on to found United Artists, which lasted until the 1980s, bringing James Bond to the silver screen, among other things. The film’s other producer was Harry Aitken, who later founded Mutual Film. Mutual later evolved into RKO Pictures, whose most iconic releases include King Kong, Citizen Kane, and the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals. Then there was Louis B. Mayer, a northeastern cinema chain owner who paid $25,000 for exclusive rights to show The Birth of a Nation in New England. Mayer made so much money that he used the profits to start his own movie studio: Metro Picture. After merging with a few other studios, Metro became Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer or MGM, a studio which still exists to this day. Warner Brothers and Fox likewise started out as theater chains that went on to produce their own movies using profits from Birth of a Nation.

Contrary to popular belief, Hollywood was founded by gentiles. The early titans of Hollywood had names such as Mack Sennet, Thomas Ince, and D. W. Griffith. Jews only controlled distribution. The Jewish takeover of largely came about when the Jewish distributors decided to cut out the gentile middle men and create production-distribution monopolies. Although in some cases, the reverse was true: Paramount was founded by William Wadsworth Hodkinson, a gentile theater-chain owner from Utah. Paramount merged with Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players — and then the Jews from Famous Players ousted Hodkinson from his own company.

Prior to The Birth of a Nation, movies were seen as a low-class form of entertainment for poor people and immigrants who could follow a silent film without having to know English. It’s where the term “legitimate theater” comes from, which implies that movies are not legitimate art. The Birth of a Nation gave movies middle-class respectability, after which huge amounts of investment began to pour in.

What was the big deal?

As I said, The Birth of a Nation is a movie that everyone knows about but few have watched, but that doesn’t mean you should. It does not hold up as entertainment. It is a slog to get through. Silent films are generally hard to watch for most people, and there are only a handful that I would recommend to someone who does not have an academic or autistic interest in them. If you want to understand how much modernity has wrecked our attention spans, try watching a silent movie all the way through with no pausing or checking of your phone. It’s not easy. Watching a silent film requires a lot of concentration. You can’t let your mind wander. A lot of the story is told through hand gestures and facial expressions, so you have to pay very close attention to what’s going on.

Besides which The Birth of a Nation is three hours long, and it doesn’t start to get really “based” until two-thirds of the way in. It begins in the antebellum South, and the Klan doesn’t come around until Reconstruction. Until then, you have to sit through a couple hours of melodrama, romantic subplots, Civil War history lessons, and Abe Lincoln. I found a YouTube video called “Birth of A Nation — scenes for teaching on racism” where someone compiled all the most racist bits, and it’s only eight minutes long.

Thus, if you watch it today, you probably won’t understand why The Birth of a Nation was such a big deal. Why did the American public go crazy over this very boring movie?

State-of-the-art filmmaking

We cannot understand The Birth of a Nation’s appeal for the same reason a zoomer who grew up watching CGI movies could never understand how I felt walking out of a theater in 1994 after having seen Jurassic Park, the first CGI movie. They could study the history of special effects in order to understand what a leap forward it was, but they will never viscerally understand how it felt to see a realistic-looking dinosaur in a movie after having only seen obviously fake-looking ones throughout your entire life.

There are many legends about what happened when ordinary people saw motion pictures for the first time. There’s one about a London audience in the 1890s who were shown a 45-second Lumiere film showing a train arriving at a station; the crowd panicked because they thought the train was going to come out of the screen and crush them. There’s another about a village in Eastern Europe in the 1930s in which no one had ever seen a movie. Someone set up a showing of a movie, and the audience was so disturbed out that people died in the ensuing stampede for the exits. Regardless of whether any of these stories are true, there is a lot of testimony that movies had big impact on people when they were new.

While The Birth of a Nation was a technical masterpiece for its time, filmmaking was still in a primitive state of development. The movie camera had been around for decades by then, but there was a steep learning curve when it came to figuring out how to tell a story with it. There are lot of basic filmmaking techniques that are now standard which were revolutionary breakthroughs when they were developed for the first time. Before Griffith, directors would simply set up a camera and let a scene play from start to finish with no cuts. Something as simple as cutting to a closeup of an actor to show their emotional reaction to something took years for anyone to think to do it. The same was true of certain editing techniques that are used heighten drama, cross-cutting between different storylines, closeups, fadeouts, angled shots, and so on.

D. W. Griffith did not invent any of these, although he may have stumbled upon some of them independently. Griffith was nevertheless the first filmmaker to efficiently integrate all these new techniques into a cohesive whole. Lillian Gish, an actress who starred in the film, credited Griffith with inventing “film grammar.” As Kevin Brownlow say in his book on silent films, The Parade’s Gone By, “The Birth of a Nation was the first feature picture to be made in the same fluid way as pictures are made today.”

Audiences in 1915 were much closer to the subject matter

Contemporary audiences saw The Birth of a Nation first and foremost as a “Civil War movie,” not as a “movie about the Klan.” The film was released on the 50th anniversary of the US Civil War, which was well within living memory of many of the people who saw it and which still cast a very long shadow over the country. For comparison, The Birth of a Nation came out about as long after the Civil War as Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan came out after the Second World War. These movies affected people because at the time everyone felt some connection the war; every kid my age had at least one grandparent who had been involved in it.

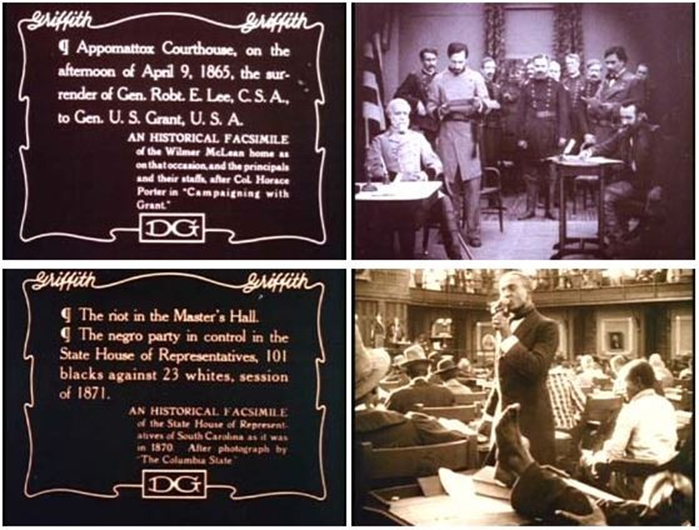

For many of those who saw The Birth of a Nation in 1915, it was the first time they had ever seen a realistic depiction of a Civil War battle; they had previously only read and heard stories about them. The film likewise offered recreations of other famous historical events, such as the assassination of Abe Lincoln and Lee’s surrender at Appomattox (and the actors playing Grant and Lee are dead ringers for the originals). This was a far greater selling point for The Birth of a Nation than the appearance of the Klan.

A major theme in the film is reconciliation between Northerners and Southerner. While the story is told from the Southern perspective, it portrays Northerners positively, particularly Honest Abe. Lincoln is shown as wanting to show leniency to the South, and his assassination is framed as a great tragedy that was responsible for the dystopian negrocacy that followed during the Reconstruction era. The cultural divide and animosity between white Southerners and white Northerners was far greater in 1915 than it has been in the lifetime of anyone alive today, which is yet another reason why no present-day viewer could “get” The Birth of a Nation.

The Dunning School

Besides being technically innovative, The Birth of a Nation was also ideologically novel. In a way, The Birth of a Nation was The Greatest Story Never Told of its time. Many who had grown up hearing only the Yankee interpretation of the war were completely oblivious to the fact that there was another side to the story. The late nineteenth and early twentieth century saw the emergence of the Dunning School, which was named after Columbia University professor William Archibald Dunning and introduced new ways of thinking about the Civil War and Reconstruction that were more sympathetic to the South. In that sense, The Birth of a Nation was a “red pill”.

The Birth of a Nation was not considered a racist movie at the time

How could a movie where some of the protagonists are Klansmen carrying out lynchings and others are sex-crazed negroes chasing young, white ingénues around a forest not be considered racist in any era? Indeed, one of the intertitles reads: “The former enemies of North and South are united again in common defense of their Aryan birthright.”

Film historian Kevin Brownlow, who interviewed more people involved with The Birth of a Nation than any other person alive, remarked on this phenomenon in a 2010 interview:

Hardly anybody that I interviewed didn’t rave about Griffith and didn’t acknowledge The Birth of a Nation as the greatest thing they’d seen. What is extraordinary to me now is that we didn’t discuss the politics. Now, I’d seen the picture as a 13-year-old with a school friend at the Everyman Theatre in Hampstead, when they were running the sound version, and the sound version is catastrophic because it’s speeded up, Griffith having shot it at 16 frames per second, [and] it’s now shown at 24 frames per second. It looks absolutely ridiculous. It’s also terrible quality, and we both came out saying, “What a load of rubbish!” But we didn’t respond to the fact that the Ku Klux Klan were the heroes and the blacks were the villains. And when I spoke to people who remembered the picture, the first time round, they all regarded it as cowboys and Indians, besides being tremendously proud of the film as a member of the industry who produced it. And raving about Griffith.

Brownlow added that Madame Sul-Te-Wan, a black actress who played a maid in The Birth of a Nation, told him that “[i]f my father and Mr. Griffith were drowning in the river, I’d step on my father to rescue Mr. Griffith.”

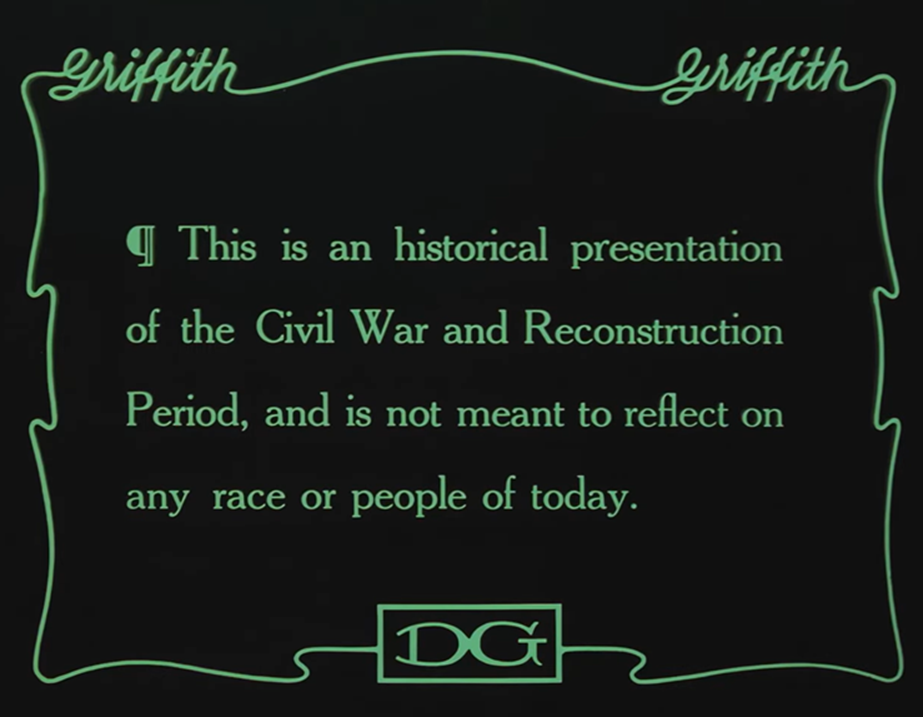

Why did people at the time not think The Birth of a Nation was racist? A hint as to the answer might be found in one of the intertitles, which reads: “This is an historical presentation of the Civil War and Reconstruction Period, and is not meant to reflect on any race or people today.”

In other words, The Birth of a Nation was showing what newly-freed slaves had been like, not necessarily what black people in general were like per se. Recently-freed slaves were not a bunch of well-spoken Will Smiths and Morgan Freemans. They were feral and had no experience of living in civilized society. The Birth of a Nation is merely a historically accurate portrait of what things were like during Reconstruction. Those watching The Birth of a Nation in 1915 understood this, although it appears to go over the heads of modern scholars.

Both Griffith and Thomas Dixon, who wrote The Clansman, the book The Birth of a Nation is based on (although strictly speaking, it was based on a stage adaptation of the book), in fact opposed the reformation of the Klan. They insisted that the Klan had been necessary in the immediate post-war period to restore order, but was no longer needed. Griffith was particularly taken aback by the accusations of racism and spent the rest of his career trying to atone for it. His next film, Intolerance, was about prejudice, and his 1919 film Broken Blossoms was an interracial love story. Thomas Dixon, for his part, remained an outspoken White Nationalist — although even he opposed the second iteration of the Klan.

Dissident Rightists frequently point out the fact that blacks are rarely villains in movies, and when they are, the hero is also black. This tradition in fact began in response to The Birth of a Nation — which actually caused blacks to riot in several major cities at the time.

As difficult to comprehend as it may be for us today, The Birth of a Nation will always remain the most significant movie ever made.

Why%20The%20Birth%20of%20a%20Nation%20Is%20the%20Most%20Important%20Film%20of%20All%20Time%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Related

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Will There Be an Optics War II?

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?

15 comments

I’d argue Conan the Barbarian is the most important film of,well,this platforms ideals context.West against East,free spiritedness against religion,virility versus meekness,individual versus the Mass,fight for Your survival instead of fooling others let you suck their blood.Even choosing a then amateur Austrian for protagonist,and wearing him a blond whig (the original “barbarian” was raven haired),and a Blackman for the Antagonist,might have been the creators blinking an eye to those among the audience who could get themselves around it.

What a fascinating article and historical context. I knew it was a famous movie, I just never realised how significant it was for the entirety and future of the film industry. I oft here of Orson Wells being the most significant director and Cecil B DeMille as the director with the large expansive sets, seems that D.W Griffiths with Birth of a Nation beat them both to it.

Shame that a centenary was missed to celebrate such an important movie and cultural event. It will always be addressed in forum and in publishers like Counter Currents, but it will never see the light of day in mainstream unless it is in a very negative context. 2 great film reviews this week – it would be great to have scope and scale to produce short and long form films that are aligned to our motivations.

In Australia the original film was actually featured on Netflix or maybe cable for a time back in 2015 with quite a fanfare about Griffith as a filmmaker. I tried to watch it but it was a slog and I didn’t at the time have an ulterior motive to plough on.

I’d argue Conan the Barbarian being the most important film for getting across this platforms ideals.West against East,free spiritedness against religion,virility versus meekness,individual versus the Mass,surviving on Your means instead of fooling others to let themselves bloodsucked.Even choosing a then amateur Austrian as the Protagonist(and wearing him a blond whig,whereas the original “barbarian” was raven haired),and a Blackman as the Antagonist,might have been the movies creators blinking an eye to those among the audiences that could get themselves around it.

Gotta chime in to say that, while I agree that silent films are mostly too boring for modern audiences, almost anything by Buster Keaton is an exception to that rule. The General is regularly cited as one of the top ten greatest movies ever filmed (for many of the same reasons stated in the article for Birth of a Nation.

But don’t take my word for it, or the opinions of critics. I don’t always agree with critics, but in this case, Buster Keaton perfected the art of visual humor (for which you don’t need audio of done as brilliantly as he did it).

Matter of fact, it was the talkie that destroyed the careers of a lot of artists like Keaton. He managed to stay relevant for a while, but the Vaudeville inspired humor that he mastered didn’t translate well to audio formats.

Silent comedies aged best. I also think that German Expressionist movies hold up pretty well.

IMO, the greatest of all silent films is Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans. It’s unique for being a Hollywood film that was made in the German style, a blend of European artistry with American production values.

Pure comedic gold? Marion Mack throwing twigs into the train engine’s firebox when Keaton tasks her with feeding the boiler.

Brings out my inner misogynist every time. Lmao

An underrated comedian of the silent era was Max Linder, the “French Charlie Chaplin”. They name-drop him in Inglourious Basterds.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ieaYv50BTdU

Tragic story though. Linder enlisted in the French army in WWI, got shellshock, and was never the same again. He and his wife committed double suicide in 1925 although some suspect it was a murder-suicide.

From what I’ve heard, the generation of Blacks who came of age after the Civil War was even more difficult (if that’s the right word for it). Only because all this has passed living memory is it possible for red diaper baby “historians” like Howard Zinn to lie and contradict what was common knowledge back then.

All that aside, another thing modern audiences won’t pick up on is the character modeled after the mattoid politician Thaddeus Stevens. That guy was a real special snowflake.

There’s Art,there is pure Propaganda,both will serve their purpose if the intent(in this case,C.C.s broader agenda) is generally positive.I think paternalistic,not to complex,quaint even films work wonders with the under 12y olds,more openly idealistic and Life affirming pictures would attract those in their teens(careful to notice that adults too excited with those two types of film are probably useful to raise our numbers,not so fit for decision making,l see elders who share my world view in love with simpleton,boring as cement stuff,and it is disheartening..),and,for the mature and possessing enough existence experience,proper Art,any art,should work just fine.Smart,honest grown ups should be in position to come with their own conclusions even in a mostly argumentative package,and even at its freemost,Art always gravitates toward the Right and the overall Functional.Art won’t escape talent,beauty,strength,sanity,even if its creator strives consiously for a confused/mostly negative stance.

I see how effectively outright “progressive” multiculti TV and film,aimed at all age groups,works,from colourblind youths unconsciously echoing Open Society vehement advocates,to comformist “well,we do need immigrants to get our pensions payed and have enough caretakers” elders.If dissonant,unnatural manipulation,so opposite to man’s root inclinations,has planted its seed so effectively,l can only imagine how an opposite realist Idealist,life affirming campaign would work.

History,and Myth.Europes struggle against Brown and Yellow invasions (Illiad,Persian Wars and Alexander,the halting of the Huns,the Moors and the Turks,Reconquista,Hungarys and Novgorod kingdoms pushing the Golden Horde back,Ivan the Terrible,the Norsemen’s centuries of counteroffensive against the biological and cultural polination of MENA into our homelands),all this should suffice as filmaking material.

Nevertheless,in the “don’t excell!” and mandatory diversity directives that nearly suffocate anything filmed post wwii,and even more so early nineties onwards mass media,a few films,even unintentedly,did manage to get the spirit across.”Troy”,the “300”,despite inaccuracies & some caricature and movie goofiness,and “Braveheart”,where l freely forego the Scots vs English context,and vision a pure Nordic communities fightback against late Roman moral degeneracy & consequent genetic decay,along with all the adjacent MENA bio/psy warfare,that by then glued itself inseparable from the Roman and began its spreading across Europe,come to mind in that regard.

Maybe it’s because I’m used to watching silent films or generally films that demand long attention spans (“Satantango”, anyone?), but I don’t consider TBOAN “boring” at all (but I like “Intolerance” much, much better). I understand that modern viewers, oversaturated by movies who need to cut and move the camera all the time, need to get used to silent film aesthetics a bit. Watching them on a big screen with good music in a good print at the proper speed can work miracles here.

I do however think that the importance of the movie and of Griffith in general was a bit exaggerated by film historians.

This had to do with the availability of prints and a certain “legend” that grew around Griffith already during his lifetime. As more and more films from the silent period were made available, restored, re-discovered and re-evaluated, it became apparent that Griffith was by far not the only director of that era who used the “film grammar” innovations ascribed mostly to him. It’s really hard to say here who did anything “first”.

For example this is largely a (quite persistent) myth:

“Before Griffith, directors would simply set up a camera and let a scene play from start to finish with no cuts.”

The truth is that these cutting techniques developed simultanously around the world, and Griffith (who started in 1908) was just one of many directors following a trend that more and more emancipated cinema from the stage.

But it is also true that he did have a genius for employing and expanding them in a way that was very innovative, dramatic and exciting for the audiences of his time. He also had a way of drawing mesmerising and vivid performances from actresses like Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford or Mae Marsh (he was especially good with women). That is often overlooked when the impact of his films is being discussed today.

It wasn’t until the 1920s when the camera really started to move and use daring angles, cutting became really fast and complex, and cinema became a totally new form of visual drama. By the mid-twenties, Griffith’s style of filmmaking was already quite old-fashioned, compared to what for example Fritz Lang, Murnau, Eisenstein, Pabst, Gance, Stroheim, Sternberg, King Vidor, William Wellman, Carl Dreyer and many others were doing. Some of his films of that era are quite beautiful (like “Orphans in the Storm”), but they were far from being “state of the art” anymore.

Another thing that was very unusual and “sensational” about TBOAN was it’s epic scale and length, which was indeed a “first time” in American cinema. It had been done in Europe before with 1914’s “Cabiria”, a film that influenced and inspired Griffith a lot (it already features intercutting and suggestive camera movements).

The big theme of TBOAN is not the now notorious KKK glorification or the tragedy of racial incompatibility (addressed at the very beginning of the film in a title that laments the shipping of Africans to North America), but the reconciliation of North and South (hence the title), a major achievement of American history, that is being undone today by demonising the Confederates and much of Southern heritage in general.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.