Why Cartoons Have Potential:

A Response to Travis LeBlanc, Part 2

White Lion Movement

1,720 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

“Anime” is simply short for “animation.” It is not some type of “con” to trick adults into watching a “cartoon,” which I have already defined in the previous part by way of debunking Travis LeBlanc’s assertion own assertions. Animation is the standard term, with several languages using shorthand to refer to the medium if no other term exists as a synonym. English has “cartoon,” but that is specific to comic-inspired drawings or satirical humor. In Japan, “anime” refers to anything animated, including animated content from abroad. The French use dessin animé to refer to animated drawings, and is a literal translation of the term from French into English. Anime has become culturally associated with Japanese animation here in North America, which has led to debates as to what does or does not count as “anime,” which I will address later.

To understand Japanese anime and its appeal to a Western audience, one must consider two things: the history of Japanese anime, as well as understand that anime is not a “genre” or a “style” of animation, but an entire medium. This article will dive into the history of Japanese anime and anime as a medium. Once that has been established, then I can address what is and is not anime, and why Western audiences are attracted to anime.

Japanese animation went through a similar process as Western animation did at its inception. It utilized comic, traditional art as well as “rubber hose” styles in various short films and propaganda pieces. The first full-color animated feature film produced in Japan was The White Snake Enchantress, released in the United States under the title Panda and the Magic Serpent, produced by Toei Animation, the studio also responsible for Dragon Ball, Digimon, and Sailor Moon. It is a retelling of the classic Chinese folktale, the Legend of the White Snake. While still made in a more Japanese traditional art style, the film also takes pointers from the Walt Disney Company by adapting folklore classics and using stylized animation. In both the pre- and post-war eras of Japanese animation, Japanese studios were heavily influenced by Walt Disney’s animated productions.

One could argue that the majority of twentieth-century and early twenty-first century Japanese anime is essentially Golden Age (1930s-1950s) Disney animation if it had continued into the 2000s. Disney unfortunately began to cut costs in their animation in the 1960s, leaving obvious pencil lines visible in the final versions of The Sword in the Stone and The Jungle Book. This trend continued after Walt’s death in 1966 and well into the 1970s, with The Aristocats. Disney’s animation would finally get cleaned up in Winnie the Pooh and The Fox and the Hound, and continued to improve throughout the 1980s and into the Disney Renaissance. This is when Disney was trying to compete with Don Bluth (An American Tale, Land Before Time, Anastasia) as well as the increasing popularity of imported animation, such as The Smurfs and The Adventures of Tintin coming from Belgium and France, respectively, and Studio Ghibli from Japan coming out with several classics in the 1980s, not all of which were solely directed at children, but some at families and general audiences as well. In 1994 Disney released The Lion King, which became the highest-grossing feature-length animated film up to that time, despite also being criticized for plagiarizing 1960s Japanese anime and manga, such as Kimba the White Lion (known in Japan as Jungle Emperor). To this day Disney creatives deny any debt they owe to the series, despite there being several similar plot points and character designs, and even similar names for some of the protagonists.

Because Disney did not face any legal repercussions, and due to Disney’s later treatment of foreign productions that they ended up dubbing, such as Digimon Savers (Data Digimon Squad, an acquisition of the original Saban Entertainment), including heavy censorship, many Japanese studios phased out their working relationships with Disney and other North American production companies, such as Saban Entertainment and Twentieth Century FOX. Disney’s relationship with Studio Ghibli likewise soured, and the latter switched from Disney to GKIDS, which is dedicated to dubbing/subbing and distributing “sophisticated” and “indie” animations from Japan, when it came to dubbing rights and theatrical distribution. Disney still retains home video distribution rights, however. This comes from a cultural push by the Japanese animation studios against censorship of their productions when they are exported abroad. If the attitude in North America is “animation is for children,” then the inverse is true in Japan. Many shows such as Beast King GoLion (known in America as the first season of Voltron) and Neon Genesis Evangelion were never intended for children, yet were adapted and heavily censored in the 1980s and ‘90s for younger audiences. In Japan, animation is a medium that encompasses all genres and all demographics. Miscommunication and culture shock ensue when Western studios adapt Japanese animation under the assumption that since some films are animated, it means they are for children.

Now that a bit of the history and culture has been addressed we can determine what is and is not anime. As far as Japan is concerned, anything that is animated is anime. Those in the know would be familiar with the in-joke of Twentieth Century FOX’s King of the Hill being referred to as “Texas anime.” Yet die-hard Japanese anime fans in the West would label anything not from Japan, yet made in a specific semi-realistic style similar to most Japanese anime to be “imitations” of the real deal. Shows such as the original Teen Titans from The Cartoon Network and Nickelodeon’s Avatar: The Last Airbender are often cited as the “poor man’s” anime.

In contrast, corporate-produced animated shows from Japan are often criticized for “losing” their anime status since their target is to sell toys and games rather than tell compelling stories. Such examples include the Pokémon and Digimon franchises, but sometimes includes Sailor Moon, as the latter is based on Super Sentai (the original source of Power Rangers). The Dragon Ball franchise is a property in limbo, as it, too, is produced with the intention of selling toys (aside from Pokémon, all the shows mentioned above are a joint effort between Toei and Bandai), although it is loosely based on the Chinese classic novel Journey to the West. The consensus from fans appears to be that narrative-driven Japanese animations which are heavily dramatized are to be considered “true” anime. In my own opinion, anime is a medium that originated in Japan with a semi-realistic — or chibi as an alternate — style open to any genre interpretation or narrative format (serial or episodic), and can be made with any demographic in mind. Content can be labeled anime or anime-inspired.

If you’ve read this far, you are probably thinking to yourself, “Why hasn’t the author addressed the reason Western audiences gravitate towards anime?” To put it bluntly, most Western animation, apart from a few exceptions, is ugly and cheap-looking. This is not to say that anime never cuts corners. There are plenty of cases where anime simply zooms in on a still frame with some light keyframing (when you manually or electronically position an object in each frame to convey movement). Anime can be just as obscene and grotesque as Western animation, but the character designs still follow a more aesthetically pleasing style, unlike the distorted look of most modern Western animation, be it for children or adults.

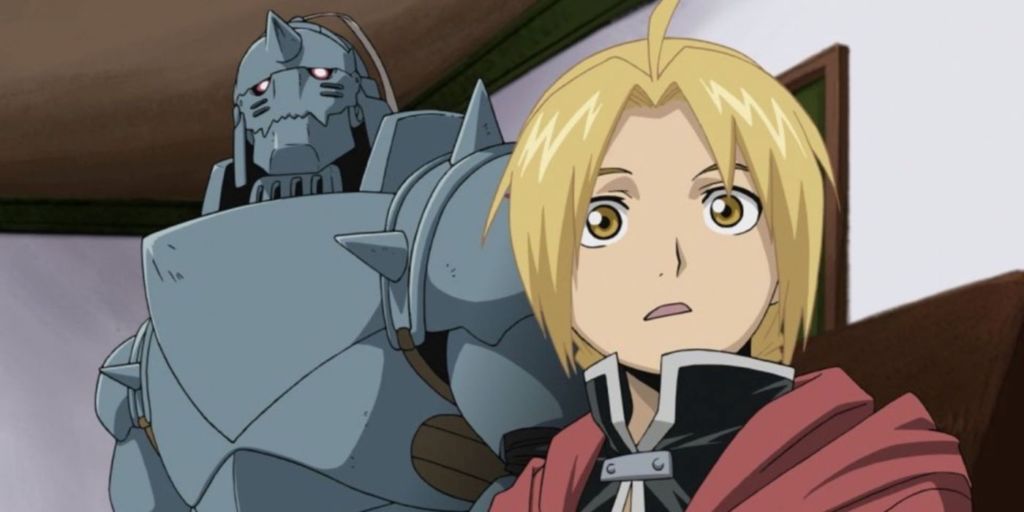

Murdoch Murdoch, while crudely animated is heavily inspired by anime style and themes. But aesthetics is not the only reason why Western audiences prefer anime over modern Western cartoons. There is for the most part more attention to detail and greater nuances in the stories and character development. Just because most anime is from Japan does not mean that it is all set in Japan or Asia at large, nor are the characters mostly of East Asian descent. Anime such as Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood, Fairytale, and Black Butler are set in a fictitious, European-like continent, set in times akin to Imperialist Era and Medieval Europe. Black Butler is set in a gothic version of Victorian England. All of them depict heavy themes that are not meant for young children. Japan does a better job of offering European-style stories and themes than the race- and gender-swap happy Western media.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

Japan does not have the same cultural pressures that the American media has. There is not as much interference by Jewish interest groups, so the Japanese can get away with showing things that could be interpreted as being “pro-white” or “pro-Western,” as seen in the recent Japanese McDonald’s ad that ended up being surrounded by a bizarre controversy.

This is not to say that anime is without flaws. Many anime shows for girls are essentially Big Mouth-style shows with better art. It can be extremely perverted, which is something I do not condone. Even shows such as Black Butler, which I mentioned above, have crossed several lines. That said, this does not undermine the cultural influence that anime has on Western audiences. People like compelling stories with enjoyable characters.

Animation has potential. If we had the right creative teams and funding, we could develop our own pro-Western style of animation and tell stories based on the Norse Sagas, ancient Irish myths, Antiquity, or even pre-First World War art styles. We can look to anime on how animation can be aesthetically pleasing while still being able to tell authentic European folktales, legends, and historical dramas — or even portray idealized futures. The argument that LeBlanc made in the second part of his article regarding “artsy fartsy” media shows a lack of understanding of how animation and media in general holds power and influence over culture. As nationalists, we should be producing “artsy fartsy” content to push the Overton window towards a normalization of nationalism, especially White Nationalism. Nationalism should not be left to the blue-collar class alone. There also needs to be highbrow content to appeal to the academic and investor classes – not to mention a wider white audience.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Why%20Cartoons%20Have%20Potential%3A%0AA%20Response%20to%20Travis%20LeBlanc%2C%20Part%202%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Will There Be an Optics War II?

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Notes on Japan: Not the Nationalist Utopia Some Imagine

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?