One of the most common reasons people fail to communicate is that they use the same terms to mean different things. For instance, “bark” can refer to the voice of a dog or the skin of a tree, and a conversation between people who don’t know they are using the term in two different ways is the stuff of comedy. In logic, we call this error “equivocation,” meaning calling different things by the same name, and not knowing it.

The concept of “sovereignty” is often used equivocally, which causes immense confusion. The two senses of sovereignty that are most often conflated are: sovereignty as a moral norm, and sovereignty as actual power — sovereignty as right vs. sovereignty as might.

The confusion is multiplied by another distinction: national sovereignty vs. popular sovereignty. National sovereignty is the moral norm that nations don’t answer to any higher political powers, but instead control their own affairs and do not meddle in other nations’ internal affairs. Sovereign nations are also treated as equals under international law. Popular sovereignty is the norm that the good of the people is the state’s highest law.

The most common objection to the norm of national sovereignty is that a nation is only as sovereign as it is powerful, meaning that only powerful nations are sovereign and weak nations have no real sovereignty at all. This implies that the equality of sovereign nations under international law is a mere fiction. It also implies that when a powerful nation invades a less powerful nation, it makes no sense to talk of a violation of sovereignty, because if a nation is weak enough to be invaded, by that very fact it has been proved to have no sovereignty.

Likewise, a common objection to the idea of popular sovereignty is that the people do not rule. Instead, powerful elites rule. Again, sovereignty is reduced to power. Whoever has power over the state is sovereign, and if you are on the receiving end of state power, you are ipso facto not sovereign. Thus, it is meaningless to criticize any state for violating popular sovereignty. The very fact that popular sovereignty can be violated proves that it does not exist.

These arguments dismiss the very idea of norms. Moral norms do not describe what happens to be, i.e., the everyday world. They prescribe what ought to be. Morally speaking, the everyday world is a mixed bag: good, bad, indifferent. Moral norms are the standards by which we distinguish between the good, bad, and indifferent.

National sovereignty prescribes that sovereign states recognize and respect one another’s autonomy. As far as this norm is concerned, it does not matter if one state is stronger than another. When one state violates the sovereignty of another, the aggressor is wrong and the victim has been wronged. This moral outrage, moreover, is not altered if the aggressor gets away with it. Indeed, the longer it persists, the greater the outrage. Evils do not magically become goods with the passage of time. But some infamies can become so entrenched that nothing can be done to reverse them.

To preserve their sovereignty, states cannot set up a power above them that forces them all to get along, because if such a force existed, they would no longer be sovereign. One solution is for smaller states to band together to counterbalance the power of larger states. Another solution is to create international bodies like the United Nations or NATO to adjudicate disputes. But if these organizations are truly international — namely, relations between sovereign states — they cannot arrogate their member states’ sovereignty. Thus, organizations like the UN and NATO are collegial rather than political. They are gatherings of independent agents working together for common aims under shared norms (international law), without an overarching power that commands them. Members of such organizations may elect leaders, delegate powers, and commission functionaries to carry out projects. But ultimate sovereignty is reserved by the member states.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s Graduate School with Heidegger here

Advocates of the norm of popular sovereignty recognize that all political orders require differences of power and that power will always be exercised by the few over the many so that the rest of society can get on with their lives. The few rule, and the many are ruled. The norm of popular sovereignty prescribes that the ruling elite act in the interests of society as a whole (the common good) as opposed to their own factional interests. When rulers fail to pursue the common good, they are wrong, and the people are wronged. This moral outrage is not altered just because the elites might get away with it. Indeed, the longer they get away with it, the greater the outrage.

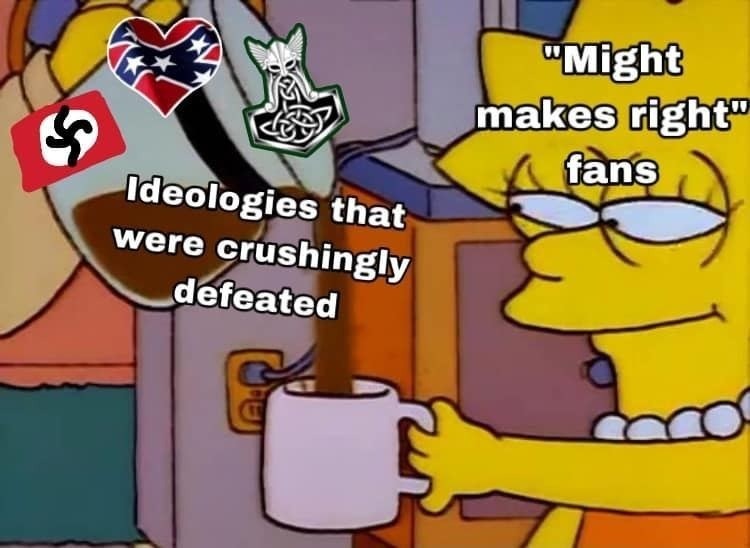

The denial of sovereignty’s normative nature is a part of a broader denial of norms as such. Often, this view is expressed as “might makes right.” But if right simply reduces to the power relations that exist at any given time — if whatever is, is “right”; or if we can never say that things ought to be different, even though we might prefer them to be — then we can dispense with concepts like the good and the right altogether and simply talk about facts.

If “right” is meaningless in politics, it doesn’t just imply that weak people have no rights. It also implies that the strong have no rights. They do enjoy more power. But they should enjoy it while they can, because when somebody stronger than them comes along and takes it away from them, they have no grounds to complain.

This is a very strange doctrine for dissidents to embrace. Dissidents by definition oppose the existing power structure. That makes us weak by definition. We might prefer that the political status quo be different. But if it is meaningless for us to say that the system is wrong and ought to be different, why would anyone who does not share our preferences take them seriously? It is a trope in Western movies to point a gun at someone and declare, “You ain’t talkin’ yer way out of this.” The truth is that, in such a situation, all we can do is talk our way out of it. In fact, one could describe the ideological component of metapolitics as talking our way into power, and nothing could be more self-defeating than declaring moral language meaningless before we start.

Fortunately, many of the “might makes right”/“right means nothing” crowd don’t really mean it. They have a very specific picture of the “might” that makes right: the outstanding and splendid individual, the kingly type, the great lion. They are revolted when you point out the simple truth that great lions can be brought down by packs of jackals. You may be big and strong, but you’ve got to sleep sometime, and when you do, a bunch of skinny guys working together can end you. The mediocre masses banded together are stronger than the splendid few. But that’s not the kind of power politics they have in mind. They don’t really believe that might is right. They believe in the inherent right of the noble to rule. But nobility is one of those pesky moral norms that they thought they had banished.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

The%20Philosopher%20Is%20In%20%20Might%2C%20Right%2C%20and%23038%3B%20Sovereignty

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy Rozdział 2: Hegemonia

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 1: Nowa Prawica przeciw Starej Prawicy

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

3 comments

Perty good. What does it say in the king’s cartouche up there? See, you didn’t think I knew things like that, but I do!

“H.N.I.C.”

Usermaatre Setepenre, the regnal name of Ramesses II.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.