874 words

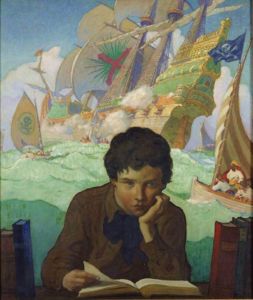

There is a natural tendency on the Right to view the act of reading as a purely utilitarian endeavor. In the hierarchy of human activities, reading is accorded greater status because reading was traditionally the hegemonic mode of transmitting scientific discoveries, lofty philosophical ideas, and arcane theological refinements. This purely mechanistic view of treating the written word as solely a vehicle for informational exchange overlooks its transcendental and transformative power. We read not only to learn, but to stoke our imagination.

Modern Western civilization has an abundance of material means, but a complete paucity of imagination. While other cultures have ossified and perished, Europeans have continually reimagined and reinvented themselves. We are natural dreamers, always in search of new dreams to dream.

With that in mind, I have chosen five novels for young nationalists that not only deal with perennial Rightist themes such as self-reliance, overcoming struggle and hardship, and identity, but which also have a heavy focus on introspection and the universe of the mind. For the generations to come, developing the creative faculty will be of paramount importance, both to imagine the world that was and to delineate a world that could be as the real, extant world continues to decay.

Knut Hamsun, Growth of the Soil

You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here.

Every downtrodden office worker and societal malcontent has idly dreamt of escaping to a cabin in the wilderness, but no novel has so vividly painted a vision of how such a life could be. The Western pioneer spirit is set loose in the wilds of Norway in Knut Hamsun’s tale of a man carving out a life and a familial dynasty while contending against poverty and the pitiless, frigid wilderness. Hamsun charts the rise of Isak from a lonely, penniless drifter battling with the elements to a married burgher and pillar of the community. The antagonists of his bucolic saga are human greed, the ever-present corrosive influence of small-town envy, and petty bourgeois material pretentions.

It is in the final pages of the novel where Hamsun truly lays out his manifesto for an agrarian Blut und Boden return to the land, decrying rootless propagators of industrial society and exploitative capitalism.

William King, Trollslayer

Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian is arguably the progenitor of the modern fantasy genre, predating the work of J. R. R. Tolkien by several years. The hypermasculine themes of violence and adventure in Conan have spawned a host of imitators, but William King’s Slayer series is a more than worthy spiritual successor. If every young boy at some stage wants to be Conan, then every adolescent eventually realizes that Conan, too, must have had an inner life of fears and doubts. That’s where William King’s Slayer series stands out: taking the visceral action and raw violence of Conan and pairing it with an introspective, grounded narrator, drawing on the huge lore and world-building of the Warhammer universe.

Hermann Hesse, Steppenwolf

Alienation is perhaps the only sane response to modern society’s monstrous nature, and the result of alienation is an intense, introspective soul searching. Hesse is a master of the human psyche, using his narrative to pose difficult questions without offering definitive answers. The entire book is a demolition of consciousness, blurring the lines between life and death, reality and delusions, and the concepts of right and wrong. These are all metaphysical themes that we must meditate on, and as we join down-and-out Harry Haller on his aimless strolls through hazy nights, the unavoidable existential conundrums are macabrely and alluringly framed.

There is an undeniable sense of the German spirit in Hesse’s work, including Harry’s dialogues with legendary German author Goethe.

Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club

In the not-so-distant past, the topic of masculinity was not one that warranted dissection; it was simply practiced, not theorized. Yet, modern society has so thoroughly deconstructed gender and displaced the traditional role of men that a reaction was inevitable. Fight Club is an explosive critique of the emasculated and domesticated modern male, and the consumerism and corporate subservience that has sublimated his natural instincts. At its heart, Fight Club explores both the physical and mental experience of manhood; the physical capacity for violence and risk-taking, and the immense loss of those who have been figuratively and literally castrated by modernity. The fighting and the struggle depicted in the novel is an allegory for the transformational pains of confronting masculinity’s central questions: Could I be better, stronger, braver? It correctly identifies that our war is indeed a spiritual one, waged in the confines of a vacuous consumer society.

Robert A. Heinlein, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

A reluctant revolutionary planning an uprising against an authoritarian society managed by a sentient artificial intelligence more powerful than its creators ever conceived is certainly a synopsis that has distinctly modern parallels, despite Heinlein penning his work in the 1960s. His descriptions of a degraded and criminal lunar society rife with polyamory, incoherent ethnic groups, and incomprehensible totalitarian diktats can only resonate with the contemporary reader. What is the probability for the success of a revolution in such a nihilistic and dystopian future? What would one even look like? This book is indispensable reading for all those seeking to change the nature of our world.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

8 comments

I read “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” in my very early teens. I’m not sure I absorbed any of the message that Veiko is describing here. Mainly I remember the Lunarites having skimpy-but-practical clothing and the main gist of the plot being about the possibility of dropping rocks on Earth as an ultimatum to assert Lunar independence.

“Space Cadet” is an appropriate alternative for someone in their teens, of either gender, as it doesn’t bother with either the overt militarism of Starship Troopers or the wrangling of Mistress. It’s a straight up science-fiction exploration story about “Patrolmen”, who are neither military nor strictly civilian, and the tradition of the service. It follows an aspiring Patrolman through his career closely, covering things like aptitude testing, life in cramped quarters, teamwork, professionalism, openness to other cultures whilst retaining one’s own sense of identity, dealing with the opposite sex whilst in service, being a tradesman and engineer in a hostile environment, improvised diplomacy in unexpected encounters, etc, etc.

The Call of the Wild, Robert E Howard’s Pigeons From Hell (that’s how race realism should be expressed in literature), Bill Hopkins’ The Leap (one of the few existential novels worth re-reading), and Westward Ho! for the Anglos among us.

Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man – James Joyce

Johnny Tremain by Esther Forbes is very good, and can be enjoyed by older children or adults. I re-read it recently and loved it. It’s about a talented young apprentice who is faced with a severe blow to his pride, and takes place in 18th-century Boston during the years leading up to the American Revolution. Lots of accurate details about colonial American life, and sympathetic portrayals of rebels, loyalists and British soldiers.

Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress has a claim to being one of the first of the cyberpunk novels. The protagonist has a bionic arm and supervises an uber-computer (with the moniker of “Mike”) which develops its own AI. Along with a couple of other cadre, they lead a rebellion of Lunar denizens against an overbearing Earth government.

There’s interesting stuff in here about organizing a revolution, using a combination of mid-20th century insurgent cellular tactics and rabble rousing out of the 18th century American Sons of Liberty (Heinlein wields the latter point with the subtlety of a sledgehammer). 21st century dissidents might take notes, though current developments in network-centric warfare have caused some of Heinlein’s 1960s assumptions to be overcome by events.

The downside is that Mike is a little too pat. Mike provides the Lunar rebels with a lot of clever cyber gimmicks which neutralize the Earth occupation forces (which appear to be a mighty thin garrison to police several million people) and then launches a counterattack using a big railgun to bombard the home planet with bigger rocks. Meantime, the Earth high command can never quite figure out that it is Mike who behind all this mayhem, much less develop counter-tactics. They have to carry the cyber-idiot ball to make the plot work.

Alexi Panshin has a brief critique of Moon in his book, Heinlein in Dimension. Among other things, he points out that while Mike continuously announces the odds for the revolution succeeding are diminishing, there is nothing in the story to support such pessimism.

Regardless, there are some things in there to give today’s dissident’s a thought or three.

Oh yeah, Mistress put into the vernacular the term Tanstaafl (there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch). Sorta like a much later cyberpunk film popularized the Red Pill.

The only fiction I’d highly recommend, a return to the early 1700’s colonial America, is Robert McCammon’s Matthew Corbett series. It’s my gold standard for storytelling and this hidden gem should be more well known than its contemporary inferiors.

Tom Wolfe’s “A Man in Full” is fantastic. One of the two main characters, Conrad Hensley” is just 23 years old but is a true example of full manliness. I highly recommend it for anybody 16 years old or older.

This is a fantastic list! I enjoyed it, especially, because “Steppenwolf”, by Hermann Hesse, has touched me more profoundly than almost any other work of fiction. It should shame me to admit this, but I did not stumble across “Steppenwolf” until I was well into my thirties. I have a beautiful little copy right here on my desk, beside me.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment