I Dream of Djinni: Orientalist Manias in Western Lands, Part Two

Kathryn S.4,571 words

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

2. Rage Militaire: Franco-American Zouave-mania

“His parents taught him to be a cavalier, but the life of the Zou-zou he much did prefer.” — anonymous Confederate verse

“The city,” one Richmond, Virginia newspaperman enthused, “was yesterday thrown into a paroxysm of excitement by the arrival of the New Orleans Zouaves — a battalion of six hundred and thirty, as unique and picturesque looking Frenchmen as ever delighted the oculars of Napoleon the three.”[1] But it was Napoleon “the one” who had begun the ludicrous Zouave military fashion craze that, decades later, gripped soldiers and civilians during the War between the States.

In 1801 Napoleon was in the middle of his Egyptian campaign. Since every self-respecting emperor before him had at least tried to conquer the ancient land of the pharaohs, he considered it a kind of duty.[2] One evening while mulling over the idea of strategically converting to Islam, the General saw a cloud of dust gather on the horizon. Before long, a company of 150 North African Mamluks had arrived at the French encampment, looking fierce and unsmiling. Their leaders offered the General their services as men-of-action, and Napoleon soon incorporated them into his Grande Armée — members of the Consular Guard, no less.

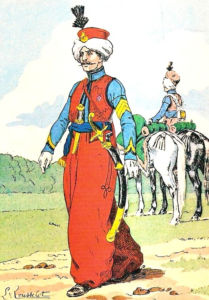

Though almost completely replaced by metropolitan Frenchmen over the course of their 13-year service to the Emperor, their members’ costumes remained suitably exotic (because, everyone agreed, they were the best part). Riders of this company wore a white turban wound about a red, green, or yellow cahouk and ornamented with a brass crescent moon and star pinned to the center; a short red, green, yellow, or indigo jacket adorned with braiding and underneath a sleeveless waistcoat; full scarlet trousers and boots peeking out at the bottom; various-colored sashes tied around their waists that each secured a dagger and two pistols; a green pouch-belt slung over their left shoulders that held a blunderbuss, and cords over the right held a curved Oriental saber.[3] In an era filled with colorful braids and epaulet-happy uniforms, these stood out. The rest of the Garde Impériale must have burned with envy.

I’m sure there are those who, like nineteenth-century enthusiasts, consider Zouave uniforms to be the height of dash. I’ve always thought them ridiculous-looking, especially when worn thousands of miles from the Sahara. But for a time, the Zouave style marked the soldier who wore it as a warrior — a man of romantic and tribal élan — rather than a conscript of the state. It tapped into stories of the ferocious jihadi Moslem fighters, renowned in Western history books as worthy opponents of Crusaders, Byzantines, and Spaniards. They made their Oriental bellicosity a vicarious element in Western arsenals. At least, that was the idea. Like the tulip, it was a celebrated (and sometimes vaguely) Eastern novelty, and like all fashions, worn for show. And when showing off, the white Zouave was seen as somehow braver, more of a fighter — more manly — than those marching in their traditional Western uniforms. Real men wore tasseled fezes and Aladdin knickers.

After the disbanding of Napoleon’s North African Guard in 1814 (following the Emperor’s first surrender and exile), the French took a short break from les vêtements exotiques, until their Algerian adventures of the 1830s revived the love affair. Upon landing at Sidi-Ferruch near Algiers, the Frenchmen experienced Napoleonic déjà-vu. 500 natives volunteered in by-now-familiar desert garb that the French took to calling “Zouave,” in honor of the local mercenaries who had come riding up to enlist. Once again, the North African style completely seduced them — but then, “uniforms of foreign troops on their own soil, whether friends or foes, [had] always captivated the French.”[4] Was it the Gallic flair for all things à la mode? As we shall see, they were hardly alone in this, their weakness for le hussard de l’Orient.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died here.

The army formed Les Bataillons des Zouaves, who were not indigenous North Africans but Frenchmen in native costumes. They distinguished themselves in the Crimea, and introduced the West to the allure of European men in Eastern uniform. “Oriental fashions became the rage,” one soldier recalled, and “imitating Madame Bonaparte, the ladies doted on turbans, and every self-respecting officer carried a Turkish scimitar.”[5] Before we blame fashion manias wholly on the feminization of culture, let us consider that militaries have always exercised enormous influence on fashion. It is true that women love a man in uniform — almost as much as the man in uniform loves his own reflection while he wears it. The confident feeling that one looks good is indeed a kind of armor . . . but one of dubious utility off the parade route.

The French Zouaves dressed differently than their earlier Mamluk counterparts had, wearing fezes and short jackets over collarless vests, open at the front and decorated with braid and red trim; a wide sash over even wider red trousers (summer white for the hottest months); and white gaiters from shin to boot. The Zouave craze swept the field as quickly and furiously as a foul-tempered Cossack would charge the enemy after missing his breakfast. Even Queen Victoria called for a British regiment of Zouaves so that she might enjoy watching them pass by her window in full Oriental regalia.

Men volunteer to go to war for various, but predictable, reasons. One of them has always been the prospect of wearing a cool outfit. When the Union and Confederacy declared war on one another in 1861, raising an army was a national project, but a very local affair. Whole towns signed up together for the same companies, and they gave themselves dangerous-sounding and often funny nicknames: the “Lincoln-Killers,” “Swamp Devils,” “Black Hats,” “Tallapoosa Thrashers,” and the eyebrow-raising “Beech-Creek Jerkers.” A catchy name was a start, but what would they wear? In thrall to the Napoleonic-French mystique, many units decided to adopt the Zouave look.

American Zouaves did Europeans one better when it came to designing these eclectic Orientalist fashions, proving that one did not need to have had contact with the East to fall under its spell. After all, allure of the exotic resists specifics. These Zouave uniforms were as varied as the places from which their members hailed, but there were some near-universal elements involved: short, open jackets with (usually red) trim; baggy, separate-legged trousers and tight gaiters; and red fezes or kepis as the topper. Union General George B. McClellan reported that “the men say this dress is the most convenient possible, and prefer it to any other.” The Zouave was the “beau-ideal of a soldier.”[6] Like many of McClellan’s wartime observations, this was a doubtful statement.

But those were early days in the spring and summer of 1861, and eager spectators who watched a Zouave company tread by on their way to the front almost always agreed that “their dress [lent] to the Corps a Martial and picturesque appearance . . . that could hardly bear improvement.” Former Crimean War correspondent William Howard Russell wrote that “the Zouave mania is rampant in New York, and the smallest children are thrust into baggy red breeches . . . and are sent out with flags and tin swords to impede the highways.” Scores of marches and musical numbers were composed to celebrate the “gallant” and “gay” Zouaves, all of whom “paraded with [a] dashing, wild, insouciant air; / With figures sinewy, lithe, and spare.” Oh, “I am tired of city life, and I will join the zou-zous; I’m going to try and make a hit, down among the Southern foofoos,” trilled one silly song.[7]

Some men seemed to use their non-white dress as an excuse to behave like non-white thugs — like marauding Bedouins. The New York Fire Zouaves (a band of ex-firefighters) was “one of the most notoriously undisciplined and unsatisfactory regiments in American history.” Clothes unfortunately made the man in too many cases. When the group crossed into Confederate territory near Alexandria, Virginia, their Colonel wasted no time in acting stupid. He stormed one of the local inns flying the Stars and Bars from its rooftop, and before he could tear down the flag, the owner of the establishment promptly shot and killed him. An inauspicious beginning.

Zouave units were not as popular in the South, probably due to what we would call “supply chain issues,” as well as the fact that Southerners were already assumed by themselves and by their Northern foes to be dashing and gallant beaux-sabreurs who didn’t need any help in the panache department. But there were a few Confederate Zouave units, one of them the notorious “Wheat’s Tigers” from Louisiana, men recruited from the back alleys and shanties of New Orleans. The local Picayune noted that “the red flowing breeches . . . the fez, the pretty jacket and the leggings of the Zouaves have been a better bait than the bounty of five dollars offered to every white man who would enlist with the regulars.”[8]

The Tigers wore red jackets and balloon-puffed trousers, striped blue and white. A red fez or straw hat completed the ensemble. Everyone commented on their hard-bitten looks that the Zouave style only served to exaggerate: a “splendid set of animals” they were, “sunburnt, muscular, and wiry as Arabs; and a long swingy gait told of drill and endurance.” As for their faces, these were “dull and brutish . . . and some of them would vie, for cunning villany, with the features of the prettiest Turcos that Algeria could produce.”[9] The Richmond Daily Dispatch seconded the visual: “They are generally small, but wiry, muscular, active as cats, and brown as a side of sole leather.”[10] Coming from Southerners who were fighting to maintain the necessary color-line, these opinions were pointed remarks. Not that the Tigers cared. In fact, they relished their bad reputation. Thinking themselves true Frenchmen, these Zouave Tigers ironically argued for the only legitimate claim to North African dress. They were “so villainous,” one officer remembered, “that every commander desired to be rid of [the regiment],” despite its effectiveness on the battlefield.[11]

As the war dragged on, most of these gaudy uniforms wore out, or disappeared. The poor-quality red dye of the Tigers’ jackets faded to dull brown, while the more brilliant accouterments worn by other units “made them conspicuous marks, and objects of special hatred.” When one grizzled Union veteran retreated from the front at Second Manassas, he taunted a line of Zouaves marching in the opposite direction: “Wait till you get where we have been. You’ll get the slack taken out of your pantaloons and swell out of your heads!” The daily grind of camp and the wear of combat muted the brightness of their uniforms, making the Zouaves look “bedraggled, even ludicrous.”

Gone were the days of preening through the town squares, for now they had no turbans, but “discolored napkins tied round their heads” and “loose bags of red calico hanging from their loins.” Seeing them clad in their “gay attire,” dead or writhing amid the tall green grass made for a sober and unsettling image — the gory leftovers of a circus troupe. “Grimed war here lay aside / His Orient pomp,” poet Walt Whitman reflected. The reality of war made a sad absurdity out of an already silly costume. I, for one, “cannot endure them,” a Union nurse admitted, “for an American citizen to rig himself as an Arab is demoralizing.”[12] It seemed that the colorful and culturally-rich Eastern tableaux failed to enchant at least one woman in the States. Why had so many people considered Oriental-inspired dress to be the epitome of white manhood — of the “ideal” American soldier? Despite their impracticality, a few Zouave regiments retained their flamboyance and clung to their floppy “pantaloons” till a Southern surrender forced them to put aside their Oriental fantasies and to put on homespun once more.

3. Chintzy Tea Parties: British Chinomania

“Our sitting-room was green and had framed and glazed upon the walls numbers of surprising and surprised birds, staring out of pictures . . . at the death of Captain Cook; and at the whole process of preparing tea in China, as depicted by Chinese artists.” — Charles Dickens, Bleak House

In the 1750s, the weekly British World published a satirical story about a woman named Lady Fiddlefaddle who, after inheriting many “beautiful vases, busts, and statues” that had come from Italy, “flung [it all] into the garret as lumber, to make room for great-bellied Chinese pagods, red dragons, and the representation of the ugliest monsters that ever, or rather never, existed.” If by reading the sensible World, “she could be persuaded to leave off every Chinese fashion, [save] that of pinched feet and not stirring abroad,” the narrator would be a “happy man.” Lady Fiddlefaddle had embraced a passion for novelty. Such a desire, inherent to the human species, can lead to advancement in the sciences and beauty in the arts. But when a society’s very raison d’être becomes an incessant search for the Something New, absurdities will occur. In this case, the absurdity was the “applause fondly given” to all things Asian, and in particular, to “Chinese decorations.”[13]

The French named this ornate style chinoiserie. In the mid-eighteenth through most of the nineteenth century, enthusiasm for Chinese objects affected “practically every decorative art” applied to interiors, furniture, tapestries, and bibelots.[14] It supplied artisans with tacky motifs of scenery, human figures, pagodas, intricate lattices, and exotic birds and flowers. “Chinomania” was a fantasy of cosmopolitanism fueled by a desire for Eastern over Western aesthetics. This kind of indulgence was tied to commodities, and therefore to fashion. The British bidding and collecting of all things Asian resulted in a novelty-madness similar to Tulipmania and just as silly-looking as Zouave-mania. All of these crazes had something in common: the collector/aesthete subordinated himself to objects, allowing them to define what he was. Westerners no longer made their own culture; instead, imported items from other lands and aesthetics borrowed from the Orient acted on and en-cultured Westerners.

“‘Tis true,” another poem “On Taste” lilted acidly,

quite sick of Rome and Greece

We fetch our models from the wise Chinese, and soon, Our farms and seats begin

To match the boasted villas of Pekin

On every hill a spire-crowned temple swells

Hung round with serpents and a fringe of bells.[15]

These caricatures weren’t exaggerations. Enthusiasts of the Orient decorated their formal rooms “like the Temple of some Indian god . . . [and hung] curtains” patterned with “Chinese pictures on gauze.” Indian “fan sticks” ornamented the chairs and “Japan[ese] satin” covered the cushions. According to Orientalists, true men and women of discriminating taste should toss European culture, too familiar to be considered culture at all, into the trash bin. Though “far distant from the Grecian, and perhaps more so than the Egyptian and Tuscan,” one British tastemaker admitted, “we are delighted to have our rooms and appartmens [sic] fitted up after the Chinese manner.” After all, “Mankind is too fond of variety to be always pleased with the same decorations.”[16] That may be, but such statements smack uncomfortably of our modern calls for more, and evermore “diversity.”

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here.

The most noteworthy examples of British Orientalism were teas and the porcelain china in which fashionable ladies served them. We must all “live up to [our teapots],” Oscar Wilde once quipped, and what better way to show off one’s impeccably sinophilic worldliness by collecting Old Blue — the most coveted of china patterns?[17] Collecting porcelain gave the middling sorts easy access to a kind of frothy glamor and romance. Britishers wrote an amazing amount of poetic praises dedicated to Old Blue, rivaling the Dutch paeans to their flower arrangements.

When sitting on their saucers there, awash in lacy-curtained light, this porcelain was ”the very blue and white of the sky, tinted by the color of heaven after rain, such as it appears between the clouds.” In place of “Augustus” and “Alexander,” British china-collectors called their favorite porcelain “Admiral of the Blue,” and “Emperor of China.” When one found himself in Old Blue’s semi-divine presence, “There [was] joy without canker or care, there [was] pleasure eternally new, [‘twas] to gloat on the glaze and the mark, of china that [was] ancient and blue.” “Ancient” meant access to an Eastern-ish culture, richer and more profound than those that were Western. “Could France, could England produce anything like it?”[18] admirers asked. Gushing Europeans thrust aside inheritance in favor of Orientalist ostentation. Stand away, Mr. Keats, and make room for the newer, better “Ode to a Chinese Urn.”

In perhaps a decadent version of ritual cup-bearing, women were the high priestesses of the china-tea service. The delicacy of the fair sex seemed perfectly suited to fussy porcelain. When serving men tea, she acted as a civilizing agent, softening his rough edges. Indeed, Victorians mused, a woman “never look[ed] prettier than when making tea. The most feminine and most domestic of all occupations impart[ed] to her a magic harmony” akin to Confucian Feng shui. There flashed “a witchery [in] her every glance.” Doing away with the Eastern tea ritual would “rob women of their legitimate,” and apparently foreign, “empire.”[19] While men went abroad to go a-conquering (perhaps in their Zouave costumes), women engaged in their own Eastern conquests a-brewing, never having to leave their domestic spheres.

But men, too, could also become possessed by chinois “witchery.” Author Charles Lamb confessed that he “[had] an almost feminine partiality for old china.” When visiting “any great house,” he felt an irresistible compulsion to “inquire [after] the china-closet” — an inquiry that should never come out of any man’s mouth.

Skeptics did not shy away from sneering at this Orientalist fashion show. Over-cultivation, they warned, made women hysterical and men unmanly and fretful, taking possession of them for life. It got to a point when “almost every great house in the kingdom contained a museum of these” grotesqueries. “Even statesmen and generals were not ashamed to be renowned as judges of teapots and dragons.” But people of sobriety might as well have been harping in the face of a typhoon.

Chinomania, slaked by teas from Ceylon, Darjeeling, Canton, and served in pauncey china cups, was here to stay. Perhaps holding too many tea parties was the real reason Wonderland’s inhabitants were batty. Collecting was a form of self-pleasuring, and the effeminate British collector, as he wandered luxuriously over the world, accumulated his foreign “poetry and music and pictures and statues,” making “amusement and travel . . . his [gods].”[20] Orientalist “cultivation he [idolized] as the substitute for the plain duty of patriotism” — and, we can also assume, his libido.

4. Rajneeshpuram, Oregon: Western Osho-mania

So far, this essay’s Orientalist flights of fancy have been about whites embarrassing and occasionally bankrupting themselves over aesthetics — nothing too serious, readers might think. I have saved the worst for last. The following case of “Osho-mania” is one (albeit extreme) example of the attraction Westerners have felt toward Eastern philosophies and religions.[21]

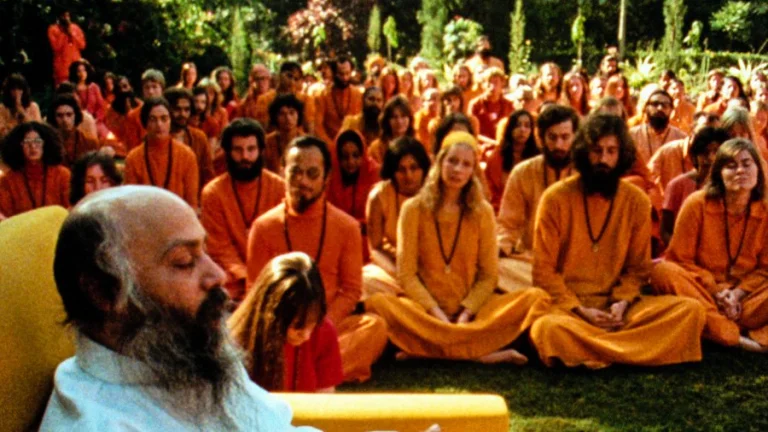

The story began in 1960s Poona, India, where a former college professor named Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (or “Osho,” as he later called himself) gathered a following of both Indians and Westerners (Rajneeshees) and built a reputation as a spiritual guru. His movement fused Hindu and Buddhist thought, while focusing on self-acceptance and self-esteem. It seemed tailor-made to appeal to young whites living during the counter-cultural 1960s and ‘70s, a time when anti-Westernism was especially fashionable.

Among Bhagwan’s strictures were aesthetic rules: followers had to wear the “colors of the sunrise,” meaning various shades of red and orange; drape over their necks a beaded pendant, called a mala; and discard their Western names and take new, Sanskrit names.[22] For white followers, it was a rebranding and an explicit rejection of Western heritage and its traditional patriarchy — the abandonment of one’s father’s name in order to venerate an Indian man, who had supposedly mastered true enlightenment. Indeed, it is hard not to see these outward manifestations of Rajneeshees’ anti-nationalism and anti-authoritarianism as a kind of fashion statement. The guru himself collected over 90 Rolls-Royces and wore several diamond-encrusted Rolexes.

When Bhagwan’s commune got into trouble with the Indian government, he decided to relocate to the United States. His Indian female “secretary” — the compelling and terrifying Ma Anand Sheela — chose a 63,000-acre site outside the tiny town of Antelope, Oregon. Upon arrival, Bhagwan’s followers swiftly built a city (called Rajneeshpuram) on land they had legally purchased by bending the truth and assuring officials and town residents that they planned to use it as an agricultural ranch. While the commune did maintain a farm, Rajneeshpuram was in no way a “ranch.” In fact, Rajneeshpuram was meant to be the booming capital of a world-revolutionary movement that would create the New Man.

At its height, the humble “ranch” housed 4,000 permanent residents; during festivals, followers from around the globe in their many more thousands descended on the Antelope area, a place that only months before had been home to 50 ranchers and townsfolk.[23] A culture clash was inevitable.

Among other alien practices, Rajneeshees encouraged nudity and sexual promiscuity, and engaged in public sex acts at all hours of the day. This, along with commune members’ aggressiveness and unwillingness to compromise with locals’ concerns, led to a dramatic confrontation between the people of Oregon and the red-clad followers of Bhagwan. Perhaps the most striking thing about Rajneeshpuram, however, was the fact that the commune was 90% white. In comparison to the majority population, Rajneeshees were highly educated. They came from coastal America, Britain, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, and Scandinavia. Indeed, Rajneeshpuram would never have existed without an army of educated, wealthy, anti-racist, and culturally-impoverished whites who flocked to Oregon from all corners of the First World, hungry for meaning and release from Western “repressions.”

You can buy Christopher Pankhurst’s essay collection Numinous Machines here.

Those “repressions” included jobs and families. Members abandoned traditional responsibilities in order to take part in this Eastern utopia deep in the wilds of the United States. The fate of the Rajneeshees’ children, both inside and outside of the commune, was neglect. Ties to one’s blood relations and to mainstream culture, the Rajneeshees severed. It was deracination on a rapid and massive scale.

The attempted Rajneeshee power-grab over Antelope and Oregonian politics was similarly ruthless. Pit-bull Ma Anand Sheela orchestrated the busing-in of vast numbers of the homeless, so that Rajneeshees could overwhelm local voters. Such tactics rallied the under-men of society against the native townsfolk. After Rajneeshpuram took over the Antelope City Council, they set up their own, well-armed pink gestapo (the “Peace Force”) and school system — all supposedly under the auspices of tolerant and liberty-loving Oregon law. Over the next few years, the Rajneeshees engaged in tactics that ranged from mass poisoning, mass drugging of their homeless flunkies, attempted assassination of public officials, attempted murder of Bhagwan’s own doctor, and mass immigration fraud — until the United States government finally declared Bhagwan and Sheela criminal fugitives. The commune dissolved.

It is unclear how much Bhagwan himself knew about Sheela’s activities (for years he maintained an untouchable, superior vow of silence only trespassed by Sheela and his drug dealers), but to say that he had nothing to do with her criminal activities sounds like the ol’, “it wasn’t the king; it was his evil grand-vizier” canard.

But especially relevant to my purposes here was the manner of Rajneeshee invective aimed at other whites — at the locals of Oregon who took exception to the new arrivals’ disruptive presence. Time and again, Sheela and her white lackeys repeated charges that locals’ antagonism was driven by “un-American” “bigotry” and “ignorance.”[24] Antelope inhabitants and Oregonians in general were “stupid,” and unable to perceive that Rajneeshpuram was exposing them to culture and offering them a chance at enlightenment. Their media statements denied that the townsfolk who already lived there had any local customs or culture that Rajneeshee followers needed to respect, or even to acknowledge. This dismissive attitude was the culmination of a long history of Orientalist fantasies that privileged the fashionable ideas of the East over the real heritage of the West; of novelty over tradition; of cultivated worldliness over racial solidarity.

For centuries, white Orientalists have wanted to bring Eastern objects and philosophies home. It was only a matter of time before their descendants brought Eastern peoples to our homes.

Conclusion

We have assumed that the World Wars are to blame for white masochism, for the Western denial of its own culture(s). This is partially true. A long history of Orientalism — of beliefs that non-white cultures are enlightened societies that have somehow gained access to more precious knowledge — must share some of the blame. Indeed, too many whites now imagine that the West is uncultured, or that its civilization is a non-culture. They ironically direct most antipathy of this sort toward nativist and rural areas where white residents have managed to retain some of our traditional customs. To be cultivated these days, one must be fashionable. He must learn — or pretend to learn — the mystical ways of the colored folk and sneer at his ignorant kinfolk, who “cling to their guns and religion.”

Cosmopolitanism may signal “cultivation,” but nothing of true culture. It is indicative of few convictions beyond calls for canned “diversity” and vacuous “cultural enrichment.” Adoptions from the East similarly signify little but a taste for the exotic; for the fashions that one can put on and take off, like a red Rajneeshee shirt, or a Zouave fez, or an air of superior worldliness. Yet, how enthusiastically we have embraced this nothing! We throw ourselves wholly and often blindly into things — we, the most idealistic race of men — and turn them into manias. This has been our blessing and our curse, to be extremophiles. Never do anything by halves!

Even if we wanted to, could we change our collective nature? As a pessimistic idealist and a skeptical romantic, this author thinks not. Let us hope that we reject this dream of djinnis and wake from our impotent stupors. Let us pray that the next sweeping passion of ours will be one for survival.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

- Fifth, Paywall members will have access to the Counter-Currents Telegram group.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Notes

[1] Richmond Daily Dispatch, June 8, 1861.

[2] Napoleon officially became Emperor in 1804.

[3] See Thomas S. Abler, Hinterland Warriors and Military Dress: European Empires and Exotic Uniforms (Oxford: Berg, 2021).

[4] Ibid., 111.

[5] Ibid., 110.

[6] Timothy Marr, “The American Zouave,” in Military Images (Autumn 2016), pp. 22-29, 25.

[7] Ibid., 25.

[8] New Orleans Daily Picayune, Mar. 25, 1861

[9] Thomas C. DeLeon, Four Years in Rebel Capitals (Mobile, 1890), 70-72.

[10] Richmond Daily Dispatch, June 8, 1861.

[11] “The American Zouave,” 27.

[12] Ibid., 26-28.

[13] Untitled, in The World; March 27, 1755; 117.

[14] “Chinoiserie,” in The Columbia Encyclopedia, by Paul Lagasse, and Columbia University, 8th ed. (Columbia University Press, 2018).

[15] David Pullins, “Robert Adams’ Neoclassical Chinoiserie,” West 86th 21, no. 2, pp. 177-200, 181-182.

[16] Ibid., 178.

[17] See Anne Anderson, “‘Fearful Consequences of . . . Living Up to One’s Teapot,’: Men, Women, and ‘Cultchah’ in the English Aesthetic Movement, c. 1870-1900” in Victorian Literature and Culture (2009), pp. 219–254.

[18] Ibid., 225, 227, 228.

[19] Ibid., 229.

[20] Ibid., 245, 249.

[21] I recommend the documentary on this 1980s commune called Wild, Wild Country (2018). I found it a balanced account that explored both the resentment of the townsfolk and the (sometimes understandable) draw to Eastern religions that many Westerners have felt. The actions taken by the state and US governments against the Rajneeshees show how our institutions once acted in our interests, as well as the frightening power federal agencies can wield when their officials decide to target unpopular groups.

[22] See Carl A. Latkin, “Coping after the Fall: The Mental Health of the Former Rajneeshpuram Commune” in The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 3, no. 2 (1992), pp. 97-109, 99.

[23] See Susan J. Palmer, “Wild, Wild Rajneeshpuram” in Nova Religio 22, no.4 (May 2019), pp. 96-104.

[24] Quotations from Wild, Wild Country.

I%20Dream%20of%20Djinni%3A%20Orientalist%20Manias%20in%20Western%20Lands%2C%20Part%20Two

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Ignorance, Its Uses and Nurture

-

Introduction to Mihai Eminescu’s Old Icons, New Icons

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

-

“Few Out of Many Returned”: Theaters of Naval Disaster in Ancient Athens, Part 2

-

“Few Out of Many Returned”: Theaters of Naval Disaster in Ancient Athens, Part 1

-

The Battle of TikTok

31 comments

Before long, a company of 150 North African Mamluks had arrived at the French encampment, looking fierce and unsmiling.

Yes, the bodyguard of Napoleon was Mamluk Roustam Raza. But he was not of Qipchak origin as originally majority of Mamluks, incl. the great Mamluk Amir Beybars Baba, were. He was an Armenian, born in Georgia/Sakartvelo.

He certainly seems to have been devoted to the Emperor. He appears in a number of Napoleonic paintings.

It was only a matter of time before their descendants brought Eastern peoples to our homes.

And in this context I would note, that the Europeans have brought home from China not only porcelain or Confucius, but Mao Zedong too. Everywhere in European cities there were and are portraits of Mao Zedong. Perverter artist Warhol has created his portrait. The stupid Left have marched with Mao´s face on their banners and shouted his citates.

As someone who spent a few years leaving in “the East,” in one sense I do agree with what you say in this essay, but not entirely. Sure, Orientalism can be taken to ridiculous extremes, as you’ve described. And of course, as a Rightist of a sort, I don’t deny that Europe has its own traditions and identities that are just as rich and valid as anywhere else. However, it is not the case that the West and the East, at least in their entirety, are on an even keel. The East — at least parts of it; I doubt this applies to China, where I’ve never been — really is more traditional and less corrupted by modernity than anywhere in the West today, the United States, which is the epicenter of the disease of modernity, most of all. In the West we are stuck with venerating the traditions and figures of our past, because the chain of transmission of tradition has been broken, but in the East these things are still alive in everyday life and permeate society.

That’s not to say that the East doesn’t have its own problems, or that they aren’t also trying to get in on the globalist pie, but it’s not really accurate to say that they have nothing to offer except perhaps a bit of interesting literature, philosophy, or art. And I really think anyone who wants to understand what a valid tradition is, especially spiritually but not only in that way, must experience the East for some time, since it’s the only way to encounter what’s been lost in the West. Then you can return to the West with a renewed understanding, both of the problems we face and what we lack, as well as what our strengths are and what might be the basis for renewal. Especially for those who aren’t Christian, an encounter with Eastern religions can be extremely fruitful given that it can help to fill in the gaps of our very incomplete record of European pre-Christian religions and practices.

Thanks, John. I don’t know if you’ve written about your Eastern experiences, but if you have, please share them. If not, then I’m sure the subject would make for interesting future reading.

I don’t disagree with you, really.

Criticizing Eastern traditions as they exist/have existed in those places was not my intent; the majority of the essay is focused on how the West has usually mishandled those traditions and turned them into fashion crazes that affluent Westerners use to show off how “cultured” they are. I use the vague term “the East,” or “the Orient,” because these fashion crazes absolutely were vague. The “Indian” bed canopies, chests, cloaks, etc. that van Oldenbarnevelt owned, for example, could have meant things from anywhere east of the Levant. The same with “Chinomania”; no one really cared whether something was Chinese, Tibetan, or Japanese.

It would be nice if we could collectively be appreciative of how “Eastern” countries have managed to keep alive “valid tradition[s],” while also maintaining restraint. Unfortunately, most of those efforts seem to devolve into desperate and frenzied attempts to simply transfer symbolism/philosophies from East to West in order to compensate for what we have lost. We tend to take away from the experience the trappings of the East, rather than any profound, traditionalist Truths (obviously I’m not talking about everyone’s experience, but in general). And transfer will not save us from our lack. As Jung (a great admirer of Eastern cultures and of the “collective unconscious” that included the Orient) said, if we tried to “cover our nakedness with the gorgeous ornaments of the East . . . we would be playing [ourselves] false. A man does not sink down to beggary only to pose afterwards as an Indian potentate.” This is the phenomenon I’m discussing in the essay. You’re talking about taking away from the Orient something different. In this respect, I think we’re both Jungians.

Eastern lands are full of worthy peoples with beautiful customs, and they may even offer hope that we can “renew” ourselves. But as an unreconstructed Western chauvinist, I don’t think our salvation will or should come from anywhere east of old Byzantium. In the end, it will have to come from ourselves.

No discussion of Orientalism is complete without a treatment of Anime and Manga culture and the phenomenon of Japanophilia in the West, which hasn’t spared even that most “intolerant” regime known as the Third Reich. Why do we especially look to Japan for our aesthetics? And further, from the Eunuch’s hashish to the Yogi’s cannabis, to the Chinaman’s opium historically and fentanyl presently, why are we held in thrall to the East’s substances? Is Western man so contemptuous of his humdrum existence that he’s willing to give his soul to these strange eastern herbs?

But maybe Mx. S will find herself assisted by a mysterious Eastern stranger in the noble task of answering these questions. Only time will tell.

Miss S. normally doesn’t speak to strangers, let alone Eastern ones with a mysterious gleam in their eyes . . . but if it’s in the interests of breaking the West free from Manga, “Pocky Sticks,” and Ganja plants, then she might be persuaded.

Revilo Oliver has written, that the Japanese, at least, their elite, are of Aryan origin. Possible some Iranoaryan tribal unions, like Alans. Moreover, the Chinese Red Zhou, were not Chinese at all, but Iranoaryans.

Some possible connections here – you might like this one:

https://thuletide.wordpress.com/2022/06/11/who-were-the-scythians-origins-culture-and-genetics/

Thanks, that´s interesting.

Is Western man so contemptuous of his humdrum existence that he’s willing to give his soul to these strange eastern herbs?

Long before the arrival of drugs from the East to Europe, Europeans were already using drugs of local origin. The most common drug was the mushroom fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), the Vikings chose from their bravest, he ate a decoction of fly agaric, then urinated into a bowl and the rest drank this “secondary product”, catching a buzz. In some countries of Eastern Europe, in which the leaders/chieftains of these international terrorists and drug addicted pirates seized power in the tenth and eleventh centuries, turning the native population into slaves and trading them in the whole Europe (such words as slave, Sklave, sklaaf, schiavo etc. in European languages prove that), these leaders are now considered “holy” princes/dukes and great statesmen.

Thank you for this illuminating portraiture of Western decline. Henceforth any discussion of Edward Said’s “Orientalism” must be coupled with your “Western” explanation.

Perhaps your next article should be on the influence of the Global South (Africa) on the increasing casual nature of Western culture, from dress (t-shirts, shorts, flip flops) to sexual practice, to speech (more direct, less obliging, more emotional), etc.

Thank you, Sesto — that is a good suggestion. At least Orientalism resulted in compelling art, like Jean-Jules du Nouÿ’s piece. At least the Orient had examples of magnificence from which to draw. “Negroism” on the other hand . . .

In the end, the Orientalism in culture is reflected in the Orientalism in politics. A French or West German leftist student in the 60s and 70s went to demonstrations not with portraits of some French or German, even leftist, philosophers, politicians or poets, no, he wore portraits of Mao Zedong or Ho Chi Minh and quotes from their statements. The huge popularity among Western audiences of Jackie Chan, and earlier Bruce Lee, was one of the reasons that the American film industry is increasingly oriented towards the tastes of the Chinese with their huge market. And therefore, for a very long time there have been no films critical of the Maoist government in Beijing, which would talk about human rights violations, both of the Chinese and residents of the occupied territories, i.e. Tibet, East Türkestan and others. The last such film was seemingly “Seven Years in Tibet” and this film was made twenty-five years ago. And it was not an American who made the movie, but a Frenchman. And hence the prevalence of Chinese “Triads”, not just supplying drugs, but also associated with ChinCom intelligence. Or the fact that Western men now are increasingly drawn to Chinese women, and among these men there are even high government officials, strategic scientists or FBI agents who are recruited by Chinese intelligence through these Chinese women (see David Wise’s book “Tiger Trap”). And, at last, the Chinese simply corrupt the governments of Western countries and give their money to fund Western politicians.

The Zouave phenomenon has been carved in stone on the Pont de l’Alma in Paris. The magnificent statue of the soldier has been used by the Paris inhabitants, and still is, as a marker for the level of the Seine. When the water reaches the neck of the statue it is time to worry about forthcoming inundations. Unfortunately, the old bridge has been replaced by an ugly modern structure. Still, the old zouave keeps watch, that is until it is replaced by the statue of a gay negro.

The history of Rajneeshpuram seems for me like the history of the early Christians in ancient Rome under Nero or a little before and after him. Those nice and good innocent early Christians have burned down Rome, but they were not bad, however villain evil Nero was bad. If Osho and his followers have been more successful we would read moving stories about good and peace-loving Rajneeshees and bad bigot Americans, as we read in Quo Vadis by pan Senkiewicz about peace-loving early Christians and bad and cruel Romans.

Chris Farley’s cultural appropriation of Eastern warriorship in Beverly Hills Ninja at least made us laugh. The NYU students buddying around with Hare Krishnas in the park next to black drug dealers make us wince. Beech-Creek Jerkers? They tour with the Butthole Surfers? Mrs. Fiddlefaddle and the wangdoodle-snozzwangers and rotten vermicious knids out there in Loompaland, I doubt her Sinophiliac passion for Chinoiserie includes soirees with people eating their cigarettes while spelunking inside their nostrils and stuffing slime bags into shopping carts on crowded trains. On the other hand, it’s preferable when the Old Blue dilettantes were just sleeping with the gardeners instead of disemboweling them on suspicion of eating her veg. And when his glitzy toys exposed his hucksterism Osho should’ve changed that name to Oshit! All in all, superb essays as usual, Miss S.

Thank you for reading, Mr. Semantic. Regarding the “eyebrow-raising” Beech-Creek Jerkers: one of the joys of studying history/literature is in the discovery that our ancestors were quite funny and adept at every type of comedy, from high to low.

Thanks for two very enjoyable articles, I particularly liked the one about the teapots. A long time ago, I lived and worked for a few years in India, Madras was still then called Madras and there was not a single house higher than two storeys. Sometimes, especially in Delhi, Bombay or Calcutta, one would encounter a group of orange people with their bells, usually all westerners. They were considered complete idiots by foreigners and locals, the latter ones utterly despising them. For their gurus, they were indeed a very profitable cattle. As for your conclusion, apostasy is the name of the game.

Thank you, Philippe. I agree. We have to collectively bring about a soul-change, or spirit-change in the West, rather than a superficial one (on this point, Mr. Morgan is correct). Too many of our “right-wing” politicians have attired themselves in the semblance of populism or nationalism, without developing deeper convictions. Fashion is easy, but fleeting; real change is hard, but enduring.

Few in the west are ready to die for their country or for principles. And these are not viewed as heroes by the rest of the population but as idiots.

There is still a tradition that upholds the catholicism that has been the backbone of the Occident, but one has to look very hard to find it.

“We have to collectively bring about a soul-change, or spirit-change in the West, rather than a superficial one”

This is such a crucial point. I have been thinking a lot during the past few years about how degraded so many white people have become. I can include myself in that judgment, considering some poor choices that I made. At least I can attest to the tremendous cultural rot which occurred just in my own lifetime, and how we really can be, and have been, a better people. These are far from original thoughts, I know, but as I get older I feel a need to stress these points.

As you have suggested, we have such a rich heritage in the West upon which we can draw for that desperately-needed renewal, with intellectual, spiritual and moral elements. Europe provides countless examples of people worthy of emulation and study, through millennia. And in looking just at America, we can consider the Colonists and Founders who persevered through all kinds of challenges, many of whom valued thought, higher culture and spirituality. Historians once remarked on how volumes of Shakespeare could often be found in humble cabins on the frontier. A lot was happening beyond money-grubbing capitalism. Children in rural communities were once encouraged to memorize Longfellow and Tennyson. There was also ugliness and materialism, but that was far from the whole story in America, and I have found it very worthwhile to delve into the lives and motivations of those ancestors.

Thank you again for your great work and thoughtfulness, Kathryn

I agree, we have the raw materials for a spiritual renewal — on the national and civilizational level, as well as on the individual level. You mentioned that you might not be proud of some things in your past (I, too, have moments when I remember something that happened years ago before I got a clue, and I cringe). But underneath the “rot,” there is something sound and alive and waiting to revel in the rich racial heritage that we have. White people face serious internal and external problems, but thank God I’m not a colored person, but a white person; a member of a race that has come closest of all to touching the stars — and if we can get back on track — might actually do that and go on to even greater things.

Thank you, Traddles, I enjoy your comments as always.

The Napoleonic Zouave craze seems redolent of the GWOT. Re the uptick in Arab mystique, brutality of the Hindu Kush, etc. Of course, a fair amount was recruiting propaganda by the usual suspects. But you can see this pronounced especially in the spec ops community’s adoption of Afghan garb as a form of ‘cultivated’, worn-in soldiering. A part of guerrilla war – sure – just as there exists a necessity for elite troops, but the strange cross between military elitist badge keeping and worldliness smacks of ‘the tribe’. American kids are practically up to their ears in this stuff.

But you can see this pronounced especially in the spec ops community’s adoption of Afghan garb as a form of ‘cultivated’, worn-in soldiering.

Lawrence of Arabia is an example of an Englishman who sympathized with the Arabs more than with his compatriots, and did not just wear Arab clothes.

I did not mention the fact that blacks loved the flashy Zouave uniforms, too (go figure), but not only because they were gaudy, but also because they supposedly represented African militancy and “black power.” The Afro-American Magazine published during the 1850s engaged in their own — and now common — Orientalist fantasies by imagining their Sub-Saharan selves as somehow related to the peoples of upper North Africa. Quoth the AAM in 1859:

“The African Zouaves, known as Turcos, are the most wonderful specimens of humanity . . . who walk about with a cat-like step as if the ground were too hot for them — the very impersonation of muscular strength . . . the wild Africans now being imported to our southern border are of materials such as could, in a certain event [!], be manufactured into a regiment of Turcos.”

As my ex-colleagues would blandly put it: “there’s a lot to ‘unpack’ there.”

Interesting, where were they from. Mauretania, Mali, Chad?

As far as I can tell from the original source (the Anglo-African Magazine based in New York), the editors seemed to be possessed by the delusion that southerners were “importing” large numbers of Africans via smuggling, and that Congress would soon officially reopen the slave trade as a legal enterprise (the U.S. outlawed the importation of new slaves decades before in 1807). Where exactly the editors thought the slaves were coming from, they did not say (probably because it was fantasy).

Because in Anatolian Türkish Negroes are called zenciler. And that word comes from the name of the Island Zanzibar, really it means “Zanzibarians”. Because Zanzibar was biggest center of slave-trading in the Eastern Africa. I do not know where the Negroes in the Osman Empire came from, but by us in the Caucasus there were settlements of African Negroes in Abkhazia (Apsny). And nobody can surely say how did they come to us. Most think they were bought by Georgian or Abkhazian princes in Africa as slaves and resettled in the Caucasus sometime between 17th and 19th century, but there is a version, that they are descendants of Kolkhis. Supposedly the ancestors of Kolkhis and Abkhazes have come from ETHIOPIA! I have never thought that Kolkhis were black, so I do not believe in that hypothesis. There are versions, that they were bought by Russian Tsar Peter I the Great (who, as many Georgians think, was partially Georgian), or that a ship with Osman slaves was wrecked near the Abkhazian coast and the black slaves were rescued and settled there. But, anyway, when we remember, that in English Caucasian means man/woman of the WHITE race, the words Caucasian Negroes sound someway strange. But they are real, and here is an old picture of them

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%90%D0%B1%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%B7%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B5_%D0%BD%D0%B5%D0%B3%D1%80%D1%8B#/media/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:Afro-Abkhazians.jpg

They are absoultely assimiliated, regards themselves as part of Abkhaz people, and are good farmers (tangerines planters). Georgians call them Shavi Halkhi, Black People. Halkhi is a Georgian variation of an ancient Iranoaryan word halk, which means people, peoples almost everywhere in Eurasia. Iranians and Afghanis say halk, Anatolian Türks say halk, other Türkic nations say halk or halyk, and German Volk/Folk as Russian polk (“regiment”) both come from halk.

Yeah, the information about the “Turcos and Zouaves” that the AAM referenced to make their case for an American battalion of Negro Zouaves was actually from a foreign correspondent (for the London Times). Whoever this overseas journalist was, he claimed to be reporting from Genoa. The city played host to Napoleon III’s army that had arrived to assist renewed efforts for Italian unification (he was mostly interested in foiling the Austrian Habsburgs). With him, apparently, were 500 Zouaves (whites in North-African dress) and 100 “Turcos.” The correspondent didn’t care much about the former — sure, they had “metals [sic]” earned during service in the Crimea, but the “Turcos!” They “were the most wonderful specimens of humanity [the writer] ever saw . . . [he] could have watched their wild, vehement gestures . . . half the day. They were chiefly black, tall, fierce looking men . . . always with beautiful white teeth.” He then compared them to the “Malay[s].”

Based on this and your story about “Ethiopians,” it’s safe to say that people in earlier centuries (before mass global exposure to almost all corners of the earth) could be very confused when it came to racial origins. Even if I did not know that he worked for the Times, I would have guessed that the author of the piece (that AAM later used), was a white European. It seems that he had minimal exposure to actual black Africans, therefore taking for granted that the darker tanned skin of the “Turcos” must have made them “black” people.

On the other hand, maybe the Turcos were more like Osman’s Abkhazians (and thank you for the link — I’d never heard that Ottoman story).

Anyway, I don’t mean to go on. Sometimes I can’t turn off the classroom.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment