About a week ago a young black employee brought back news from the ghetto (colored folks are now the only reliable and honest sources left when it comes to these sorts of adventures). Earlier that afternoon, “authorities” had placed her high school on lock-down. A student had marched through the front doors with a gun and then began shooting up the place. Only notoriously bad black marksmanship prevented the school from becoming an abattoir. He then turned and fled, hiding somewhere inside the building (supposedly). Hours later and at the time she was regaling me with tales of this latest episode of local black pathology, police still hadn’t found the shooter. “That means we get a holiday tomorrow,” she said.

A holiday?

I smiled neutrally and thought, my dear, we must have very different definitions of that word. Were the shutdowns, shuttered restaurants, closed schools, and empty theaters of 2020 just part of an extended holiday, too?

But that wasn’t all, she continued. Incidentally, it was her new principal’s first day on the job. That morning, he had also tried to break up a black girl “cat fight” and suffered a fractured cheekbone and facial stitches for his trouble. “Not a smart move,” she reasoned. “He should’ve waited for the campus cops. Schools like [hers] need a principal with experience,” not a callow one stamped and sent out from the “Teach for America” mold. These violent episodes have little to do with environment or funding, she admitted, nor can anyone blame ramshackle buildings. The school is the newest in its district. “At least,” I replied, “your newbie principal will have a holiday to reconsider his career path.”

Snarkiness aside, what is a holiday, anyway, if it’s not a school-shooter lock-down, or a COVID quarantine? Perhaps no cultural phenomenon more clearly shows the character of a people than do their holidays — those times when they put aside their everyday chores and work regimens so they can participate in a religious and/or civic celebration rite. Thus, what and how Europeans have holidayed has changed throughout their histories, mirroring their shifting priorities. Pomp and circumstance served the needs of state, and sometimes the state served the needs of pomp. Local festivals bound neighbors to one another, even as they could overturn the existing order for a wonderful day of topsy-turvy privileges. What feasts and warm fires! How the children sang and skipped, and the women, they clapped! How their eyes must have twinkled at the sight and made old men young again! Alas, readers, the great white holiday — in all its manifold forms — has been replaced, and left behind only a phantom melody of a memory, a dancer twirling crookedly in her music box, dusty and half-wound. But once, very loved (in fact, something like it was a favorite Christmas gift of mine, a long time ago), and filled to the brim with wishes, wonder, and the conviction that the song would always repeat on command. The day itself, that particular date and year, may have ended like all the others and then vanished for good. But the holiday — it would always come ‘round again. Lovers of history and cheer, let’s reminisce about yesterland, what their traditions revealed about the past and, ultimately, what they reveal about ourselves.

Ancient Triumphs: Age of Victory and Military Splendor

You can buy Greg Johnson’s Truth, Justice, & a Nice White Country here

The ancients held the masculine vying for victory and participation in public contests — the dual guise of sportsman and warrior — in reverence, and their holidays reflected this obsession. It is fair to say that in general, Greeks viewed warfare in terms of competitive sport, and Romans viewed competitive sport in terms of warfare.[1] Mirror images of one another. Roman gladiatorial games, for example, were fought as mock “battles” and duels to the death inside the arena. Many gladiators were themselves ex-soldiers who had lost their wars against the Roman legions, and were then subsequently sold into slavery. Ancient Greeks, on the other hand, compared the bonds between the close formations of hoplite warriors to those close friendships formed in the gymnasium.

At the Olympics, that most beloved pan-Hellenic sporting event held during the Greek golden age, free Greek men, not slaves of other nations, registered their names for the lists. Holidays — even amidst the fierce Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) — were often observed in order to keep unbroken the ancient tradition of the region’s sporting culture. In 412 BC, the Lacedaemonian allies under “Agis gathered at the Isthmus of Corinth to prepare for a campaign together . . . [all of them] eager to revolt against Athens.” But the Corinthians, “even though others were impatient to sail, had no” intention of going with them “before they celebrated the Isthmian Games which were to take place” over the following weeks.[2] And so these Spartan allies sacrificed military advantage for the sake of civilian competition. It seemed they prized glory in their games more than glory on the battlefield.

Nearly seven decades after the last angry spear had been hurled in the Peloponnesian War, a young Athenian named Phrynon was traveling alone during the Sacred Month to the Olympic Games as a would-be competitor. Halfway to his destination, he was “seized [upon] by some troops of King Philip of Macedon . . . and robbed of everything,” save his life. Full of righteous indignation, he walked back to Athens and asked the elders there to appoint him as an ambassador, “so that he could approach Philip and ask him for the return of his stolen items.” Persuaded of the justice of his mission, the Athenians granted his request and sent him north. When Phyrnon’s party arrived at Philip’s court, the king received them “kindly . . . and gave back to Phyrnon everything his soldiers had robbed and more in addition from his own pocket.”[3] He then “apologized that his men had not known that it was the Sacred Month” — the extended Grecian holiday that protected both spectators and participants under the sacrosanct cope of Attica’s Great Games. It mattered not that King Philip was at war with much of Thessaly and Greece; the Olympic peace had to be honored.

Although known for bringing its own version of peace, or the Pax Romana, to much of the known world, Rome and its festivals exalted the city’s martial spirit. 300 times throughout its thousand-year dominion, ancient Rome celebrated a special kind of holiday. Men and women left their homes and market stalls to witness one of the most exciting events in their lives. To us, “triumph” means general success, but to the Romans, a triumph was a highly stylized ritual — a rite through which the state recuperated from the strains of war and ushered in well-being once more. Granted approval by assembly and Senate, a general returning home from a great conquest would parade through the “Triumphal Arches” of Rome and into its spectator-filled avenues, then process all the way up to the Temple of Jupiter, whose heights commanded Capitoline Hill.

The entire city emptied its buildings and gorged the paved streets with a pressing flood of humanity. Romans did not separate their public and private lives the way we moderns do, and “holidays” did not mean a chance for travel or quiet solitude away from the hustle and bustle of city life. On the contrary, it gave them no excuse for missing the hustle and bustle, for this holiday was a spectacle that fêted that most important of Roman traditions: glorious military victory. It was every citizen’s civic duty to cheer their legions and the conquering hero who had led them against the “barbarians” abroad. The entourage showcased riches plundered from the army’s campaign; soldiers sang bawdy songs about their commander, linking his achievements in battle to those in the bedroom. “Citizens, lock away your wives! The bald adulterer has arrived!” Cæsar’s men shouted from the streets. Exotic animals pacing their cages thrilled bystanders. Defeated chieftains, stumbling in chains beneath the shadow of the Roman eagle, were the objects of humiliation (and often execution). Meanwhile, the star general threw coins and other treasures to the ecstatic crowd, for liberality was rewarded with popularity — the real currency of the realm.

And as Rome grew in size and splendor, triumphs also increased in their extravagance. Plebs expected an elaborate show and a generous bounty of precious metals and stones (when they believed a triumph had failed to adequately deliver these, nasty things could happen). But no one would have accused Pompey Magnus of stinginess when he rode through Rome in 61 BC, for all the chroniclers agreed that it was a party of “unparalleled splendor.”[4] At the front, a boy in a white toga held aloft a golden moon whose sparkling light glitter-pricked the air around gawping spectators, dizzying them with stars that danced in their eyes.

This was Pompey’s third (and final) triumph. In fact, he could at that moment claim superiority over any Roman general before him. He was the first commander to celebrate “his third triumph over the third continent” as lord of Europe, Africa, and now Asia — richest region of the lot.[5] His countrymen salivated at the prospect. And Pompey did not disappoint. He arrived with “one hundred and twenty-three thousand pounds of silver” to enrich the treasury and line the people’s pockets.[6] Books, rocks hacked from a sacked city’s walls, foreign captives dressed in their national costumes — nothing was off-limits. Somewhat bizarrely, Pompey rode next to a portrait head of himself made completely out of snowy white pearls. “We have paraded even trees in triumphal procession,” a participant remembered ruefully. And if readers can envision the busy diorama of a “mountain like a pyramid made of gold with deer and lions and fruits of all kinds; a golden vine entwined all around; [and] followed by a musaeum [a shrine to the Muses],” also made of pearls and crowned with a sundial — I salute you for your imagination.[7]

But the most welcome sight of all was Mithridates’ throne, the spoil wrested from the latest vanquished king and offered up as proof of vengeance before the throng. Some years before, King Mithridates of Pontus had declared war on the Roman Republic by massacring 80,000 Romans who had made their homes in his and his allies’ kingdoms — an atrocity shocking even by ancient standards. The only shame was that the fiend had committed suicide by poison before he could be captured and forced to drink from the bitterer cup of Roman retribution. But his royal chair would do fine. As if this impressive booty weren’t enough, Pompey also claimed to be wearing the cloak that had belonged to that other Magnus, Alexander of Macedonia. Triumphs in general and Pompey’s in particular sent a clear message: “I am a virile, generous man, and I lead that most powerful of Roman institutions: the legionary army. So, please mind your manners around me.” Although future warlords like Napoleon would emulate Roman practice by marching beneath the Arc de Triomphe, at no other time would a Western nation fetishize battle to this extent. The only things worth celebrating were heroic deeds and the Roman sons who won them for their patria.

Moreover, Romans cared for no conquest in the arena like they did for military conquest. The “war game” they waged for nearly a century against Carthage would not bank its fires for any “sacred games.” In the contest for the Mediterranean, their Carthaginian rivals had scored against them in the most humiliating manner: the African had appropriated the Roman holiday. As ex-dictator Quintus Fabius raged to his son,

The Carthaginian copies us and carries the consul’s axes, and his lictors bear blood-stained rods. The triumphal procession of the Roman passes from Rome to Libya. And . . . do the gods force us to witness this also? — victorious Carthage measures the downfall of Rome by all the heap of gold that was torn from the left hands of the slain![8]

As Rome had lost to Carthage in battle, so they had lost their holiday traditions, for the Roman considered them to be one and the same. So, it was fitting that when Scipio Africanus returned from victory against Carthage at the Battle of Zama (202 BC), he also returned to his city its triumph. In procession before the delirious crowds “went Syphax . . . with the downcast eyes of a captive, and wearing chains of gold about his neck. Hanno walked there, with noble youths of Carthage; also . . . with black-skinned Moors and Numidians.” As one voice the citizens of the city sang: “Hail to thee, father and undefeated general . . . Rome tells no lie, when she . . . calls thee the son of the Thunder-god who dwells on the Capitol!”[9] Africanus, the Triumphant, knelt at the feet of Jupiter and for none other.

Medieval Ceremony: Age of Princely Magnificence

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here.

With the slow-motion collapse of Rome in the fourth and fifth centuries AD, its power bled away to other corners of Europe. No longer would the continent be dominated by petty chieftains, but by monarchs who wished to confer on themselves legitimacy via the legacy-mantle of Rome. What better way to signal their claim than through magnificent and visual largesse — than through orchestrations of spectacular displays? But magnificence was not simply the advertisement of wealth and power; it was also an invitation, for its close linguistic association with magnanimity was no accident. A ruler of true magnificence was a generous one, and he showed his subjects love by appearing among them in processions, by providing them meals and entertainment, or by involving them in church ceremonies. Like the Olympics and the triumphs, Magnificence was ever reliant on its public nature, and its propagandists hoped to inspire an ecstatic awe and contemplation among those who bore witness to its grandeur. Indeed, magnificence could not be a common affair, but only princes of church and state would be allowed to flaunt (and share) abundance before the commons. Medieval magnificence borrowed some of its sensibility from Roman triumphs and Greek games of skill, for all three were holidays sustained by an enraptured audience and a victorious leader. Choreographies of power. The chivalrous ideal in medieval tournaments married the martial focus of Rome to the sporting and rule-bound culture of Greece.

Arthurian epics directly linked the Camelot king to an inheritance from Classical societies. According to legend, “it was . . . Æneas and his renowned [Roman] kindred who laid under them lands, and [these] lords became of well-nigh all the wealth in the Western Isles.”[10] The Grail itself had traveled with Joseph of Arimathea’s line, from the deserts of the imperial Near-East to the moors of Britain, where Arthur’s Round Table assumed the title Knights of the Holy Cup. Readers of medieval romances will have noted the loving attention their authors paid to magnificence. Descriptions of richly decorated rooms, tapestries of golden and silvery weave, feasting halls, and the glittering raiment of warriors as they prepared for combat — all of these filled pages worth of space more than characterization or plot. The Middle Ages had a flair for large and lavish productions, but its people also had a passion for intricacy. Alongside enormous vaulted cathedrals were painstakingly-made miniatures, triptychs, and holy books.

Holidays during Arthur’s reign were thus imagined as appropriately majestic and detailed. Fanfare heraldry caused the hearts of viewers to rise high and flutter against their mortal cages. Christmastide meant “merriment unmatched and mirth without care.” Lords to the court came at carols to play; “the feast was unfailing full fifteen days, with all . . . gladness and gaiety as was glorious to hear, din of voices by day, and dancing by night . . all the bliss of this world they abode [there] together.” Meanwhile, attendants brought forward a feast and a “multitude of fresh meats on so many dishes that free places were few.” Each pair of guests enjoyed “twelve plates . . . good beer and wine all bright.”[11]

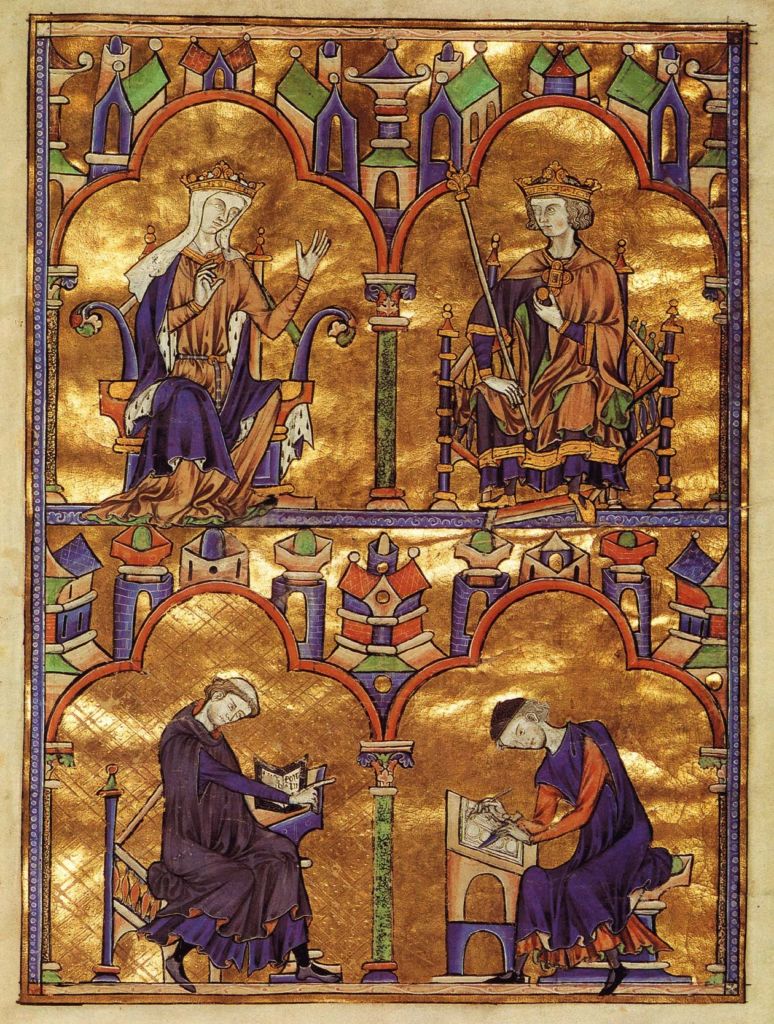

But magnificence did not belong exclusively to myth, for kings used real scenes of magnificence to create around themselves a mythical aura. A crown worn as a halo. An orb held up as a symbol of divine dominion. Saint Louis of France (Louis IX), for example, commissioned the Ordo of 1250, a liturgical manuscript in which an array of blue and golden illuminations memorialized his coronation ceremony. One of these images showed his subsequent procession as he rode through the town, full entourage in tow, suggesting that the King wished for the people of Reims[12] to see and applaud him. Solemn ritual thus became a magnificent spectacle. Although the event itself was, like all performances, ephemeral, the manuscript preserved some of its power for posterity. Even a man unable to read the Latin text would have understood the Ordo’s message. Indeed, this was Louis’ aim: to elevate the Capetian dynasty by combining in his royal person the religious and the sacred to that of worldly politics; to reconcile the paradox of the King as an anointed layman.[13] Beginning with his coronation and ending with a parade, the Ordo illustrated a cycle in which Louis used his new sacrality to win the love and loyalty of the French people. In other words, he was a national king with Rome’s transnational blessing.

A wonderfully preserved illuminated page from a thirteenth-century manuscript. It depicts Louis IX with his mother Blanche of Castile, and a churchman/cleric and layman at the bottom symbolize the king’s connection to both worlds as united in one royal person.

One must appreciate that in the Middle Ages, ordinary folk did not enjoy a world rich in color. The dyeing process was both rudimentary and expensive. They thirsted for beauty and color, for they did not take for granted the brilliant hues that now we can simulate easily. Festivals, tournaments, and the rituals of pageantry were therefore all the more vivid to the medieval eye.[14] This was the reason artists labored for decades over illuminations like the Ordo and stained-glass windows for their Gothic cathedrals; why kings and courtiers favored cloth of gold, scarlet and purple robes, and blazing pennants of family heraldry. Imagine too, the relative quietness of the world in which our ancestors lived. No engines or radios caused the air to vibrate with a man-made storm, so sounds were dramatic. Paired with color, drums and trumpets made stunning accompaniments to holidays dedicated to throne and altar. Ironically, the modern world is more drab by comparison. A sensitivity to the marvelous was essential to the appreciation of majesty.

As the knight’s role in warfare diminished during the late Middle Ages, tournaments became pure pageants and social occasions. Costuming and disguise had long been a feature of holiday competitions, but by the fifteenth century, they had grown more elaborate. In 1428 Philip “the Good,” Duke of Burgundy threw an extravagant midsummer fête meant to impress a coterie of Portuguese ambassadors, complete with staged “challenges.” While at supper, “knights and gentlemen, fully armed and equipped for jousting,” entered the duke’s hall on horseback as they approached the table where the lord and lady of the feast were seated. “Without dismounting, the knights bow[ed] and present[ed] [their] host” with a paper message, “fixed to a stick-split at the end” of their lances. Each stated that they were knights “with such-and-such names, which they had chosen,” and that they had traveled from distant lands — “the deserts of India,” “terrestrial paradise,” “the city beneath the sea,” to seek their adventures. One chevalier approached the dais “all covered in sharp spines,” like a morningstar mace made manifest. Another came orbited by “the seven planets, each nicely portrayed according to its special characteristics.” Having heard word of the lord’s magnificent feast, they journeyed to his court, and “now declar[ed] that [they] were ready to receive anyone present who wish[ed] to perform a deed of arms with them.” After having read this message, the herald replied to each man, “knight, you shall be delivered.”[15] Then the mounted “strangers” exited the hall to await combat. The ambassadors were delighted at the show.

Early-Modern Carnival: Age of Popular Revelry

Coronations, progresses, and christenings were sights that ordinary people enjoyed and that bound them to a hierarchical “Chain of Being.” The unquestioned authority was God the Heavenly Father, followed by His anointed King on Earth. All very dignified. But there were other traditions celebrated alongside royal/noble magnificence: the city carnival and country fair. The rowdy festival was the royal ritual’s foil. A sixteenth-century French lawyer admitted that “it is sometimes expedient to allow the people to play the fool and make merry, lest by holding them in with too great a rigour, we put them in despair.” If these “gay sports” were to be abolished, “the people [would] go instead to taverns, drink up and begin to cackle, their feet dancing under the table, to decipher King, princes . . . the State and Justice and draft scandalous defamatory leaflets.”[16] Popular festivals could both perpetuate social values while mocking the political order. These included farces, parades, floats, Maypole dancing, masquerades, and charivaris — all held according to need and the liturgical calendar (e.g. the Twelve Days of Christmas, the week before Lent, All Saints’ Day, “Our Lady of mid August,” etc.). During the French Feast of Fools at Christmas-time, the parish elected a choir boy as head bishop, then held burlesques miming the Mass. The lower clergy sang foolish songs and “led an ass around the church.” Lyon, meanwhile, appointed a “Judge of Misrule” and a “Bench of Bad Advice.”[17]

A detailed tapestry from the late Middle Ages that shows ordinary people (and what appears to be a wealthy couple near the bottom left) enjoying an outdoor harvest and grape-stomping festival.

Carnival in seventeenth-century Naples flooded the streets with carriages and masked revellers, creating a “raucous and joyous atmosphere.” Each social group parading past “had the opportunity of expressing its own messages . . . often in competition with others, including mocking and subversive displays.”[18] The Mardi Gras paraders of 1540 Rouen claimed to “hold up ‘a Socratic mirror’ to the world.” Business had been so abysmal that season “that the procession began with an elaborate funeral for Merchandise, followed by a float bearing . . . a king, the pope, the emperor and a fool playing catch with the globe of the world.” Toward the rear there trailed a group of “Old Testament prophets uttering riddles with reference to current political responsibility for pauperization and religious troubles.”[19]

Men who beat their wives too harshly, or wives who beat their husbands, were lampooned and disciplined by the community. Grocers who charged exorbitant prices were dunked in the river and fake coins thrown at their heads. Charivaris also targeted second marriages for tongue-in-cheek censure, its participants pointing their fingers at “la ‘Vieille Carcasse, folle d’amour’ (‘old carcass, crazy with love’),” or at the old man “surely incapable of satisfying his young wife.” A 1540 proclamation supposedly issued by the Abbot of Cornards was nailed to a post near the town square and then read aloud: “all men for 101 years [could now] take two wives.” When asked the reason, jokesters replied that “the Turks have put out to sea to destroy Christendom and we must appease them by becoming polygamous.”

This was the age in which the comic realm became the preserve of the “vulgar masses,” a second world that existed apart from “power and the state,” apart even from the official Church. As one scholar put it, the traditional customs of the peasant “[were] in nine cases out of ten but the detritus of heathen mythology and heathen worship.” Village festivals of harvest queens “[were] but fragments of the naïve cults addressed by a primitive folk to the beneficent deities of field and wood and river.”[20] Country souls held onto pagan sensibilities and would look out over the tangled growth that swarmed the surrounding forests — wild, impenetrable, and scented in the night — and then meet their fellows by moonlit rite.

Though popular revels traded in turning the world upside down through mockery, “licence was not rebellious.” At the end of the holiday, the vast majority of peasants and party-goers returned to their normal lives, some of them having received “rough justice,” and a more or less friendly warning to correct their behavior. Fat Tuesday gluttons settled into a Lenten fast. Carnivals’ satire of noble magnificence expressed both an independent and communal spirit that was central to ensuring the village’s continuity from one generation to the next. Kings held court in towers high above, while the stars of noblemen rose and fell in favor. But the village and the neighborhood would persist as immediate realities. Life was short, and the toil long. Why not play? Make fun of their betters and themselves for an afternoon, or two?

Victorian Gathering: Age of Comfort and Joy

You can buy Greg Johnson’s Here’s the Thing here.

As readers may have noticed, before the nineteenth century, holidays were public affairs. The concept of “private life” only matured during the Victorian era. Western Europeans and Americans still loved a good dance, parade, or village feast, but they began to place an emphasis on intimacy and the small family group. Industrialism and market economies created a hectic, noisy, cutthroat world that could be profoundly alienating. Thus, the household became home — a refuge from the grubbiness of public life; a protected private sphere in which love, rather than dry obligation, bound the family unit together. During the American Civil War, the separation of loved ones from their families only strengthened the desire for home and wholeness — particularly at Christmas. The fact that most men were civilians for whom war was a temporary hiatus from their “normal” lives contributed to their feelings of homesickness. Before enlistment, only a small percentage of them had ever ventured more than 100 miles from their birthplaces.

One Confederate soldier named Tally Simpson languished in a miserable tent near Fredericksburg when he took out pen and ink, and on the morning of the 25th of December, 1862, composed a heartfelt letter:

My dear Sister,

This is Christmas Day. The sun shines feebly through a thin cloud, the air is mild and pleasant, [and] a gentle breeze is making music through the leaves of the lofty pines . . . All is quiet and still, and that very stillness recalls some sad and painful thoughts. This day, one year ago, how many thousand families, gay and joyous, celebrating Merry Christmas, drinking health to absent members of their family, and sending . . . wishes for their safe return to the loving ones at home, are today clad in the deepest mourning in memory to some lost and loved member of their circle . . ?[21]

One of the few things men like Tally Simpson had to look forward to was the sending and receiving of letters. With an emotion whose consuming power rivalled the fear of death in battle, soldiers who received no letters from home turned away from the postman in quiet devastation.

Two years later, in the city of Richmond, Virginia, a lady diarist wrote at the close of 1864 that “another annual revolution . . . [has] brought us again to the Christmas season, the third since the bloody circle of war had been drawn around our hearts and homes.” Anxious children peered into the faces of their mothers and fathers “for an intimation that good old Santa Klaus” would come despite the storm of war; “that he would make his way” through the fleet at Charleston, or “the blockade squadron at Wilmington.” Would he pass the pickets unnoticed and “bring something to drop in their new stockings, knitted by mother herself?”[22] Imagined scenes of domestic sentimentality pulled at Victorian heart-strings. How long before Johnny came back and reunited the family around the glow of a winter fireside, the warmth of his homecoming chasing the chill away? Perhaps never. All the more reason to cherish the thought.

Our British cousins over the sea also indulged in the image of holidays celebrated within the privacy of family apartments. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843) was perhaps the most well-known Victorian story to use and dramatize this arrangement. There was Mrs. Cratchit lifting the goose off the stove; there was Peter trying to look sophisticated with his upturned collar; there was his sister Martha home at last; of course, there was sick and saintly Tiny Tim. Childhood had become recognized as a separate category of human existence by the mid-nineteenth century. No longer were they little adults-in-training, but a protected species to whom innocence and special love belonged. When “at last the dinner was all done, the cloth was cleared . . . and the fire made up,” the Cratchits “drew round the hearth.” At Bob Cratchit’s elbow sat a jug of spiced cider, which he “served out with beaming looks, while the chestnuts on the fire sputtered and cracked noisily.” He raised his tumbler and proposed a toast: “ ‘A Merry Christmas to us all, my dears, God bless us!’ Which all the family echoed.” Tiny Tim leaned “close to his father’s side upon his little stool,” and Bob Cratchit held his “withered little hand in his” as if he “dreaded that he might be taken from him.”[23] Yes, Ebeneezer Scrooge’s change of heart would save the Cratchit family from Tim’s loss and thus a loss of its wholeness. But the real power lay in the Cratchit family’s ability to save Scrooge from the loss of his soul. By becoming an adopted member of his clerk’s family and mending the relationship with his nephew, Scrooge learned “how to keep Christmas well.”

Real or fictional, these writings revealed that, to Victorians, the perfect holiday meant a family gathering. There could be nothing worse than to be parted from loved ones, for this was a space and time that served as a sanctuary against violence, poverty, and the pitiless world of business that all preyed on its victims outside the front door.

Conclusion: Age of Exhaustion and Debt?

Sometimes, we fail to take the play-element in our cultures seriously enough. Despite the changing practices of holidaying over the last 2,500 years, there were some important continuities. People recognized that recreation and enjoyment were central to maintaining national, local, and kinship bonds. What and how we have celebrated always revealed what mattered most to us as a people, as a race. And each age had something to recommend it — Greek spirit and Roman patriotism; medieval beauty and early-modern playfulness; finally, Victorian devotion.

In this time of the “Great Replacement,” it is worth considering what has replaced our holiday traditions. Lately, we have riots, not parades (and many parades have instead been the scenes of murderous rampages). Instead of festivals, we have “vacation time” and “Cyber Monday” sales. Mostly meaningless work has deadened us to the savoring of special days when we do not work, and stores in the United States close for holidays grudgingly. Multicultural societies that insist on celebrating “everything” will celebrate nothing at all.

When was the last time Americans held cavalcades for a meaningful triumph? The statues of our military heroes are being removed and melted down. When was the last time our leaders seemed magnificent, rather than ridiculous; inspired by God, instead of their pocketbooks and their monumental vanities? When was the last time a festival or homecoming parade invited anything but tepid support, a going-through-the-motions ritual applause that clings more to half-remembered ghosts of people who have faded from grainy photographs? No, we are told instead to observe Juneteenth, “Black Friday,” and bad Thanksgiving football (and apparently school shootings). A “Roman Holiday” only calls to mind a black-and-white film from an earlier, better-dressed era. Our thought-leaders have attempted to ruin our holidays and have declared besides that none should look forward to Christmas (except as an opportunity to shop), Thanksgiving, the Fourth of July, or Columbus Day. At least not until we have all denounced our grandmothers and grandfathers for the joy they once took at their own celebrations of these same events, and a lifetime ago.

We don’t remember when it was that we stopped hearing the little Yule dancer pirouette in her box. We only know that its music, its circular rhythms that spin ‘round like the calendar year, still pulses through us and thrumming on the foggy edge of consciousness, like a coded message without a key. When a people no longer values their cyclical traditions, their victories, or myths; when they no longer observe the feast days and pageants meant to reenact them — they become a no-people. In the future nation we hope to create, we must have these in some form again. A few of our holidays will be ancient, and more will have to be made anew. And let us, too, have comfort and joy within the family home. But I must end. I’m startled as I look up to a window full of night sky. It grows later and darker as the year winds itself down. So, I’ll borrow a few words from a Christmas master and say that “I have endeavored to raise” the Spirit of holidays past. May it “haunt [your] houses pleasantly,” but thoughtfully.[24] After all, we are what we celebrate.

Notes

[1] I realize this is a sweeping generalization of two complex civilizations, but this sport/war worldview does seem to lay at the heart of many of the differences between ancient Greece and Rome.

[2] Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War in Stephen G. Miller’s Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2013), 68.

[3] Demosthenes, De falsa legatione, Hypoth, in G. Miller’s Arete, 68.

[4] Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 51.

[5] See Mary Beard’s The Roman Triumph (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2007), 12.

[6] Ibid., 15.

[7] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 173.

[8] Silius Italicus, Punica, James Duff, trans. (London: William Heinemann, 1927), 671. The “gold torn from the hands of the slain” is a reference to the hundreds of rings Hannibal Barca collected from Roman aristocrats after the calamity at Cannæ (216 BC).

[9] Ibid., 700; Syphax was King of western Numidia and was an ally/vassal of Carthage, while Hanna probably refers to Hanna, Hannibal’s distinguished nephew.

[10] Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl and Sir Orfeo, J. R. R. Tolkien, trans. (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1975), 25.

[11] Ibid., 26.

[12] Medieval French kings held their coronation ceremonies at Notre Dame de Reims, not in Paris.

[13] See Jean-Claude Bonne, “The Manuscript of the Ordo of 1250 and Its Illuminations,” in Coronations, János M. Bak, ed. (Berkeley, Ca.: University of California Press, 1990) pp. 58-71.

[14] See Richard Barber’s Magnificence and Princely Splendour in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2020).

[15] Richard Barber and Juliet Barker, Tournaments (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 1989), 43.

[16] Claude de Rubys, Histoire veritable de la ville de Lyon (Lyon: Bonaventure Nugo, 1604), 501.

[17] See Natalie Zemon Davis’ Society and Culture in Early Modern France (Stanford, Ca.: Stanford University Press, 1975).

[18] Gabriel Guarino, “Taming Transgression and Violence in Carnivals of Early-Modern Naples,” The Historical Journal, 60, no. 1 (2017), pp. 1-20, 5.

[19] Davis, 98.

[20] Ibid., 118, 122-123.

[21] Excerpted from Richard and Tally Simpson’s collection of letters called Far, Far from Home, ca. 1870.

[22] Sallie B. Putnam, Richmond during the War (New York: G. W. Carleton & Co., 1867), 267.

[23] Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Books (Oxford: Oxford World Classics, 2006), 52.

[24] Dickens, 6.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Democracy: Its Uses and Annoying Bits

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

The Nature of “Black Culture”

-

Reflections on the Confederacy and Its Relevance Today

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Introduction to Mihai Eminescu’s Old Icons, New Icons

-

Police, in the Real World

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

16 comments

In his Iliad, Homer devoted 130 verses to the description of Achilles’ shield.

Thank you for this beautiful essay and all your work at CC, Kathryn S.

Merry Christmas to you and yours.

And Merry Christmas to you, La-Z-Man, and thank you. Those old epics were clearly the products of societies that took pride in their handicrafts. The loving attention that gets paid to boats and their sails, armor, weaponry, clothing/textiles in the Iliad, Odyssey, Beowulf, Sir Gawain, Roland, etc. is easy to skim or skip over when reading, but they really are a central part of the stories — framing the kind of world the authors and their characters came from.

As Herodotus said: “a good story never comes amiss to the judicious reader”. And you have weaved together several beautiful stories from our European past.

Thank you, and Merry Christmas to you Kathryn S.

Thank you, Nemesis. A very happy Christmas and New Year’s to you and your family as well!

Ooooh I love it when Kathryn weaves into her essays bits about Confederate experiences and the Confederacy, generally. Sensitive (in the best way) and reflective writing.

This essay inspired me to watch “Roman Holiday” again. This is a great time of year (a cozy time of year) to catch up on some classic movies. When beauty was still valued in this country.

I am sadder (and more angry, too) this season than I was even last season when we were all locked indoors. It’s because I dread the near future and what is going to have to happen to change things so we (or, our descendants) can live enjoyable lives and attend Christmas festivals and shop without hassle or harm. But I’m not depressed or in despair. Just sad and angry. I am come here to CC because I appreciate the clear thinking in the essays and in most of the comments. Everybody facing facts, no matter how grim.

I said “Merry Christmas” (rather than “Happy Holidays”) to two separate people in a gift shop today in a very lefty institution, and both of them (both white) replied with the same greeting (and one, a woman, lit up in the eyes behind that stupid face mask and waved enthusiastically — and I don’t really know her). It was a great day, just for these two experiences. And Greg’s recent essay (about Christmas) inspired me to do it.

Merry Christmas, Kathryn S.

Merry Christmas, Greg Johnson.

Merry Christmas, all.

And a Merry Christmas to you, Desert Flower! I’m glad you got an enthusiastic response to your greeting. Over the past few seasons, I haven’t had many negative reactions to “Merry Christmas” myself; most people have either politely responded in kind, or, like your acquaintances, seemed almost grateful.

I haven’t seen Roman Holiday in a long time, and I should watch it again. I remember loving Audrey’s very 1950s neck scarves when I first saw it. And never fear, I will always endeavor to insert the Confederacy into my writing. Sometimes, I think that half of my conversations with people end up as a commentary on the Civil War. The times aren’t wonderful, that’s for sure, but I do take comfort in the words of the many southerners who survived that catastrophe. I love how, in that very nineteenth-century way, they could be sentimental and long-winded one minute — and then the next, say something straight-out, honestly, and baldly.

Things aren’t so bad these days. We now have Kwanzaa to celebrate! 😉

I can honestly and happily say that this is the first I’ve heard the word “Kwanzaa” this season!

December 26th is my Christmas. The festive build-up is nice and cute, but my inner Frank Cross from Scrooged just wants Santa to get it over with and kick off the good bowl games (preferably without visits from ghosts or spooks). This yankee hasn’t transplanted himself into the old Confederate south yet, or Florida like the winter bird Ebenezers up here do. Ah yes, Kwanzaa. Tis the season for vulture brains off muti vendors. Cheers to the holiday tradition of yore, the merrymakers of all white peoples, and a jolly Merry Christmas to the Counter-Currents family.

The same to you, my Yankee friend. And I hear you. The pre-heart-growth Grinch can at times seem like the sympathetic one (if only he were nicer to Max). Even though I like the Midwest, I miss the South terribly, it calls me home. I’m determined one day to move back.

Thank you, Kathryn S, for this wonderful essay: intelligent and articulate, but also — a rarity for tellings of our history nowadays– both honest about and respectful of our ancestors and their worlds, so very different from ours.

Merry Christmas.

And thank you for reading, Dr. ExCathedra! History is wonderful, because it’s a beautiful mix of continuity and change. The ancient Romans can seem so like us one minute, and the next very alien. Our basic natures never alter, but our expressions of them do, and that is the most fascinating thing about the past, in my opinion.

Merry Christmas to you, too.

This is a great essay! Thank you, Kathryn S! I don’t think I’ve read an essay of such scholarship in a venue such as this one before. I love its conclusion! This type of analysis of festivals like Christmas is usually relegated to Jewish confines—like those of the New York Review of Books—so it’s nice to see it in a truth-oriented venue.

Dear Sesto Fior,

I’m glad you liked the article! I’m biased, but I think C-C is the best right-wing rival to Jewish intellectualism — and certainly more interesting than the latter’s tiresome takes on the West and the Western canon. The best advice I can give is to take a deep dive in the archives here. If you’re like me, it will be a mentally stimulating (and often humorous) delight!

KS

Dear Kathryn, many thanks for a very enjoyable essay.

Un Joyeux Noël à vous et à vos proches.

Mon cher Philippe,

Comme toujours, merci bien. Que la magie de Noël vous apporte joie et bonheur!

KS

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment