1,994 words

Bruce Gilley

The Last Imperialist: Sir Alan Burns’ Epic Defense of the British Empire

Washington, DC: Regnery Gateway, 2021

So, read Wretched of the Earth if your professor assigns it — by all means. Just as you should read Hitler’s Mein Kampf, DiAngelo’s White Fragility, or Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist. Understand what these words represent. Then argue back. Tell your professor they are professing an evil creed. Take your C grade, and chalk it up to a real education. — Dr. Bruce Gilley

Bruce Gilley is a Professor of Political Science at Portland State University. In 2017, he was “cancelled” by a woke mob led by a Canadian Maoist professor after writing an article about the positives of colonization. As a result of this Maoist attack, Gilley’s proposed book series about the Problems of Anti-Colonialism was put on hold by the publishing company. Then, in September of 2021, a new publisher took up the project, and The Last Imperialist is the result.

The Last Imperialist is a well-written book about Sir Alan Burns, a British civil servant who served in the Colonial Service. Sir Alan was born in 1887 and raised on the West Indian island of Saint Kitts. He came from a prominent white family that had been involved in governing the West Indies in various way for nearly a century. In 1896, Sir Alan and his family barely survived a ferocious riot on Saint Kitts that was only put down by the timely arrival of a British warship carrying a contingent of Royal Marines.

In 1903, Sir Alan became an unpaid intern for the Colonial Civil Service. The British Empire was at the height of its power, but the foundations of that endeavor had shifted and cracked as a result of the dreadful Boer War in South Africa (1899-1902). By the end of the war, many in Britain started to question whether or not maintaining colonies was worth the effort.

For Sir Alan, the answer was obvious: The British Empire was very much worth it, despite the costs. The West Indies and greater Caribbean region were a perfect place to hold a natural experiment in empire versus decolonization. “Once you started thinking about the alternatives, colonial rule by a relatively liberal and law-governed state like Britain willing to spend time and resources on your country’s economic well-being was preferable to the tragic alternative of premature self-rule as it came to life in places like Haiti and Guatemala,” he wrote (p. 20).

After he was given a salaried position, Sir Alan carried out his duties above and beyond the norm. Working with a friend, he compiled an Index of the Laws of the Federated Colony of the Leeward Islands and of the Several Presidencies Comprising the Same. It was published in 1911. Later that year, Sir Alan was posted to Anguilla. His career took off when he was ordered to Nigeria in 1903. His first assignment there was to travel up the Benin River to relieve a customs supervisor who had gone mad.

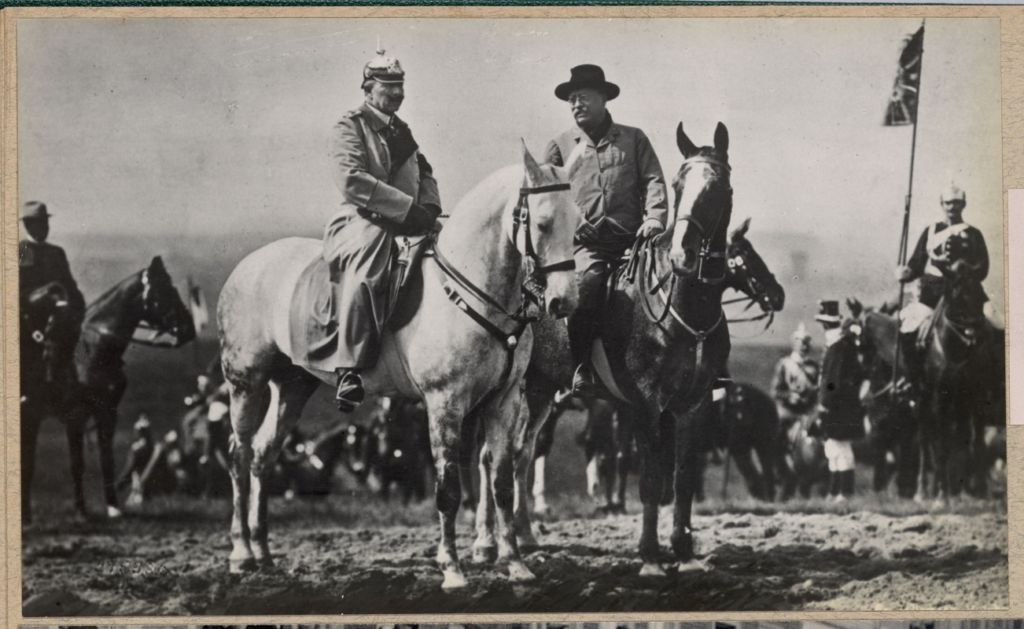

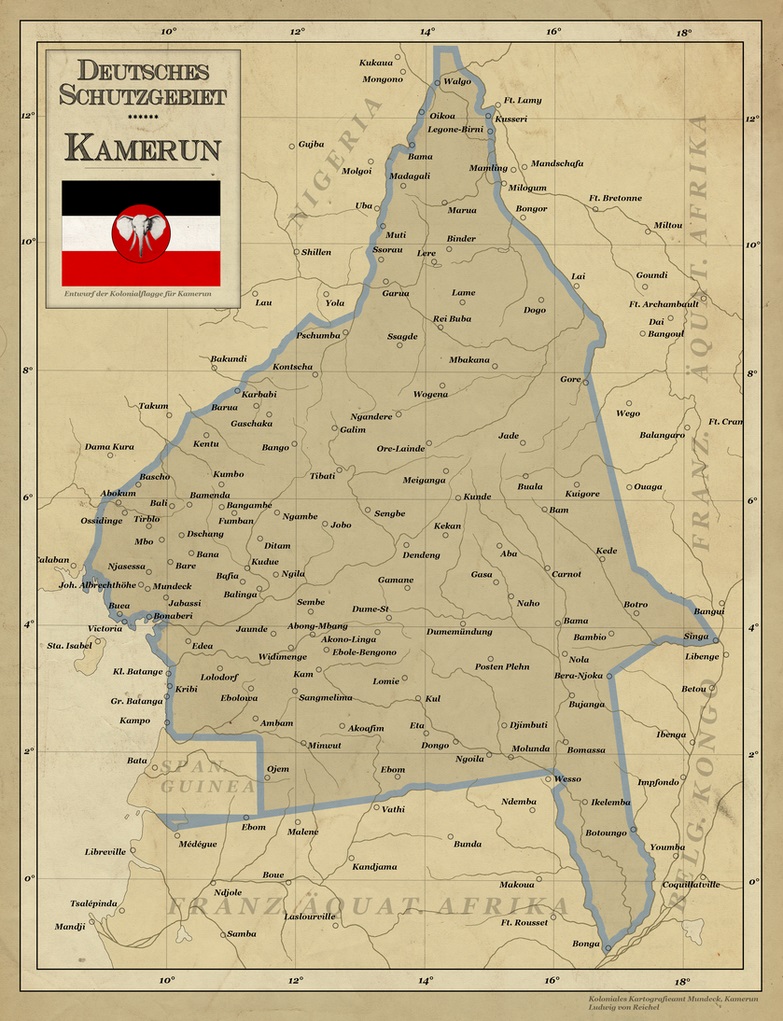

Soon thereafter, Sir Alan married Kathleen Hardtman, a local Saint Kitts girl who had roots in New York. When the First World War broke out, Sir Alan enlisted in the Nigerian Land Contingent as a sergeant. He eventually went on a campaign to capture the German colony of Kamerun. It was a tough fight, but eventually the British prevailed.

Sir Alan published The Nigeria Handbook in 1917. The book became a bestseller and he sold the rights for a considerable sum, enough to set his family on a firm financial footing. From Nigeria he went to the Bahamas. Although he was a civil servant, he chose to run for a position in the colonial legislature. After he won, he effectively became the colony’s ruler. The British West Indies were considerably self-governing, so a colonial official who was also elected to local office was very powerful indeed. Furthermore, the actual Governor was more interested in golf and swimming than in governance.

One of his main challenges in the Bahamas was alcohol smuggling. The United States had enacted Prohibition, and the fact that the Bahamas are so close to the US meant that smuggling created many thorny diplomatic issues that Sir Alan had to navigate.

The Bahamas were also rife with racial politics. The activist Marcus Garvey, whom Bruce Gilley called a fraud, visited the Bahamas to promote his back-to-Africa ideas. Garvey’s gave a speech to mixed reviews, partially because the Bahamans were comfortable being part of the British Empire.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s The White Nationalist Manifesto here

Sir Alan was posted to British Honduras as the tensions that led to the Second World War were building. There, he was faced with advocates for independence who were poor and organized by wealthy locals who wished to establish closer relations with the United States. Sir Alan was able to beat them off by insisting that they remain only one faction in the colony’s larger political ecosystem while simultaneously convincing the British government to invest in infrastructure, mostly roads, waterworks, and sewer systems.

There was some discussion about settling Jewish refugees from Europe in British Honduras, but it never came to pass. This section of the book is a bit of a smokescreen. Any historian who writes about a politician in the 1930s from a positive standpoint must claim that he cared about Jewish affairs in Europe at the time.

It is clear that Sir Alan understood the problems inherent in Jewish migration and he likely didn’t want to create a Zio-mess in Central America. The problems we see today in Occupied Palestine are the result of the end of British colonialism rather than “settler-colonialism” per se, for example.

During the war, Sir Alan worked to gain American support for British war aims, especially the plan to obtain destroyers in return for bases. The British were given approximately 50 American warships in exchange for the US receiving bases in the West Indies and Newfoundland.

Later in the war, Sir Alan served as Governor of the British Gold Coast colony in Africa. He continued his progressive economic policies there and was involved in supporting some cloak-and-dagger escapades in Africa related to Vichy French colonial support for the Axis powers. A notable event was when Sir Alan hanged several African tribal leaders for a ritual murder. The British Parliament got involved in this affray, virtue-signaling against Sir Alan and generally stirring things up in an anti-imperial way. After he left Africa, he worked for the United Nations to support continued British colonial efforts and worked hard to try to turn Fiji into a functional democracy.

End of Empire

Empires and colonies are difficult to maintain. The imperial power must balance the aspirations of a large number of people who may have different aims with the needs of the empire’s central core. The British Empire dissolved at its core, not in the colonies. Professor Gilley doesn’t mention the problems that led to imperial collapse — but I will.

The Americans and Germans were props that supported the British Empire, but when the British went to war against Germany and needed American help, they gave anti-Empire forces in both places the opportunity to cause lasting damage.

The British political elite made a series of poor decisions starting with the Jameson Raid in 1896, running through King Edward VIII’s abdication, the decisions that led to the Second World War, the Labour Party’s nationalization of key industries, and finally the Suez Canal crisis. The British didn’t resume making wise decisions again until Prime Minister Harold Wilson kept the British out of the Vietnam War and Enoch Powell gave his “Rivers of Blood” speech.

The consequences of these poor decisions were the Boer War, the “Coal Crisis” in the winter of 1946-47, unnecessary food rationing, and the Second World War and its associated disasters, including the fall of Singapore, the loss of Tobruk, and the destruction of the British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem during Operation Market Garden.

Even the British alliance with the United States was fraught with problems. The America First faction didn’t just go away after Pearl Harbor. They continued to influence domestic American politics, and they made the Lend-Lease Act such a hard bargain that it ultimately led to British industry and investments being transferred into American hands. After the war, the British needed to borrow money from the US as well, leading to debt that was a drain on the British economy until 2006.

The two wars with Germany were also tremendous disasters. The Germans and Americans were uneasy props of the British Empire, and when those two rivals were empowered to do damage to the Empire, they did as much harm as they could. This didn’t end with the war, either. Afterwards, many Nazis fled to Egypt and continued working to damage Imperial interests from there. This is not to mention the fact that the Soviet Union, which was a British ally throughout the war, turned on Britain as soon as the war was over and began aiding anti-colonial movements everywhere.

A Universal Civilization?

Gilley points out the many positives of the British, Portuguese, Dutch, and French empires, but these empires were not all alike. He also highlights those who remember the British and Dutch empires with fondness.

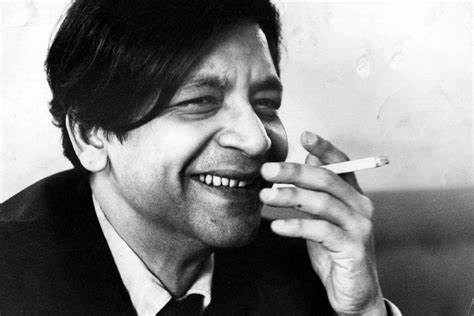

Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul (1932-2018) was a Trinidadian supporter of British imperialism. His best work was an examination of the non-Arab Islamic societies. He argued that the cultures of Malaysia, Indonesia, Persia, and Pakistan were cut off from their ancient roots by Islam and were left adrift and unmoored in an ever-changing world.

On his YouTube channel, Professor Gilley argues that the British Empire created a universal civilization in which people like V. S. Naipaul, a non-British/European, could thrive. However, Naipaul was an outlier. He did not have a high-caste Hindu background was not from India; he lived among sub-Saharans, which was quite red-pilling. Naipaul’s best works are about the closing of minds in Islamic, non-Arab nations, which was carried out by the elites in the respective nations. Thus, the Mongol and Arab empires were not enlightened polities. The universal civilization and its accompanying best societal practices could only be applied where British people were in charge and able to set the tone for the rest of society to follow.

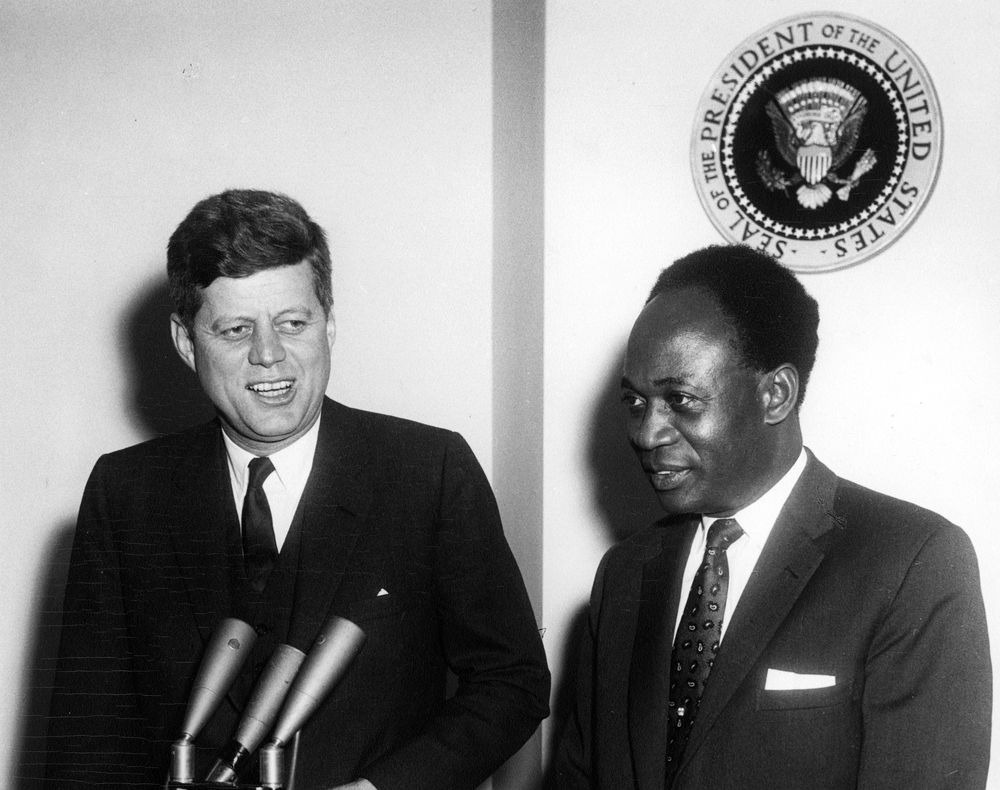

Kwame Nkrumah was the sort of African who liberal whites like to worship. In the 1960s, Americans, especially in the Democratic Party, were smitten with African independence activists, even after they turned their nations into hellscapes.

The best way to end is by telling the story of Joseph B. Danquah, a Gold Coast independence activist who was taken seriously in the wider world until the Gold Coast colony became independent Ghana. Under British rule, Danquah was treated quite well, but after independence, he was imprisoned by his rival, Kwame Nkrumah. Danquah’s appeals for help fell on indifferent ears at the United Nations. Once the white man was out of Africa, people just stopped caring. Danquah subsequently died in prison as a result of poor treatment.

Nkrumah was a lowbrow Maoist who destroyed his nation’s economy through his idiotic policies and eventually became a sub-Saharan tyrant. Thus, Sir Alan Burns should be held up as a politically incorrect, but ultimately excellent, example of what Nkrumah was not.

Sir Alan passed away in 1980. He lived long enough to see the disasters that ensued from decolonization, but nobody in positions of power cared. Professor Gilley argues that there will be calls for some new form of colonies in the future. He makes the case that former colonial powers should develop districts, such as what the British did in Hong Kong, along the African coast and other places to serve as an example to emulate.

I’m uncertain if neocolonialism is a good idea. If whites are engaged in a Darwinian free-for-all against other races, allowing these peoples access to Western Civilization’s societal practices is a bad idea.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

The Significant and Decisive Influence that Leads to Wars

-

Get to Know Your Friendly Neighborhood Habsburg

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

9 comments

The British Empire was the closest thing to the late Roman Republic the New Era was going to get. The British Empire was in character essentially a rational, not terribly philosophical oligarchy endowed with a very good sense of judgment and self-preservation. The Englishman’s manner of bearing was very much Roman – dignified but not at all sentimental, noble and refined but not effeminate, austere but not fatalistic. British attitude abroad was quite like the Roman – absolute determination coupled with a great detachment (althought Romans were, unlike the British, quite a bit vain). British administration also very much resembled Rome – a great degree of informality counter-balanced by a very keen sense of responsibility for the public matter.

There’s a case to be made that europe, as in us, was made in Escape From the tyranny of Rome (Walter Scheidel). not to mention that rome, as seen apart from, let’s say Coriolanus, was a vehicle for a deadly rampant bureaucracy and spread of nazarean superstitions.

As the means of transportation and navigation developed, empires and colonization were inevitable, in part because of the quest for knowledge and improvement that has been such a prominent feature of some European cultures. And, of course, there were the different levels of cultural development of colonizers and many colonized, which had to be managed somehow when contact was made. Motives for colonization varied, but often they involved a yearning for self-improvement and opportunity, a desire to enhance the standing of the mother country, basic self-interest and more idealistic enterprise. All of these motives can and did have very positive results.

A key question was how to manage the colonies for the benefit of the mother country, the colonists and the natives. On the whole, the British, French and some other European empires did a very good job of balancing these interests, if one looks at their whole history. Anti-colonialists cherry-pick certain negative occurrences and ignore the broad, much more positive picture. Some Africans are finding today that Chinese imperialists are not as sensitive to their desires as the Europeans tended to be. And of course the former colonies wouldn’t have the physical, economic and cultural infrastructure that they have hugely benefitted from, if it wasn’t for their imperial past.

I’m not so sure that the British and French should be blamed for the outcome of the Suez incident in 1956. I think that, by that time, many European statesmen were becoming more realistic about the fading of their colonial power, yet Nasser took a quite aggressive action to seize the canal which was a very strategic asset, and it was the United States that put the pressure on Britain and France to withdraw.

Some back of the envelope math leads to the conclusion that my mother, the child of Welsh evangelists, was born in the Bahamas during Sir Alan’s reign as overlord. No doubt his wise rule created the atmosphere that led to the development of characteristics of my own personality, such as my sense of aloof Zarathustrian serenity.

“I’m uncertain if neocolonialism is a good idea. If whites are engaged in a Darwinian free-for-all against other races, allowing these peoples access to Western Civilization’s societal practices is a bad idea.”

It’s a very bad idea. The more disengagement we can achieve and maintain, the better. We should never hug the tar-baby again.

“It’s a very bad idea. The more disengagement we can achieve and maintain, the better. We should never hug the tar-baby again.”

VERY well said!

There was a strand of idealism in the British Empire which should be acknowledged, but the main impetus was competition with rival European powers for the acquisition of resources. Nowhere is this more starkly exemplified than in the exploits of the British East India Company. I would suggest William Dalrymple’s excellent history The Anarchy to any seeking a factual account of the formative period of the Empire — and the brilliant yet ruthless men who won it.

Would this perverse globalism be possible without European colonial adventures?

The White colonial globalist administrators created a non-White class of intermediaries whose descendants have been running a racket of “anti-colonial progressivism” ever since their globalist White masters left their colonial acquisitions to their ancestors.

Both of these groups of men have little or no regard for those [Whites & non-Whites] who reject this materialist universalism.

my 2 cents, soon to be 0,07 cents

There’s a great speech sean gabb gave to what remains of english nationalists, can’t be bothered to link it now. essentially yes, it was a force of civilisation, a white man’s one.

there are some problems with brits imperialism

the great game and, ‘balancing’ according to the mackinder doctrine, or whatever you wanna call it, the geopolit swagger, which not only ruined white solidarity, but gave rise to jewish takeover of the west under the guise of another scientic doctrine (like democracy and marxism wasn’t enough)

i come intellectually largely from the west, but in central europe the ocean was seen largely like a hostile force in revisionist history recently, earlier by the french and the germans, the ottomans too, by roughly 2 centuries. not to mention that puritans were some of the first judaized/weaponized ‘frens’ that weren’t crushed by real euros whatever you imagine they to be.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment