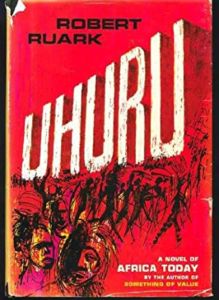

It seems that the great race novel is all but forgotten.

When it was published in 1962, it spent half a year on the New York Times bestseller list. According to the blurbs on my tattered paperback, the critics loved it. It was a huge success. And today? All but forgotten. You will have a difficult time finding much information about this this singular work of literature on the internet.

The novel is called Uhuru, and its author is the highly-accomplished American writer Robert Ruark.

I will state unequivocally that Uhuru is a must-buy and must-read for all white identitarians, race-realists, and dissidents, regardless of where you live. Anyone on the Right will inherently understand the high worth of Uhuru as well. This is a magnificent, excruciating, exhilarating, disheartening, massive story which gets to the bloody heart of black and white like nothing else. My copy has 670 pages, and the novel probably could have lost perhaps only 30 or 40 of those. It must be read with the greatest urgency. There is no story like it that I am aware of — although Ruark’s earlier novel, Something of Value, deals with a similar subject, and may get reviewed by me in the future.

Uhuru is Arabic for “freedom,” and somehow found its way into Swahili — and East Africa. By 1960, it was on everyone’s lips — especially in British-controlled Kenya, where the story takes place. British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had just given his famous “Wind of Change” speech and pledged the decolonization of British Africa. For the Kenyan black majorities, it meant the joyous — but of course naïve and misplaced — hope for freedom and prosperity. For ambitious black leaders, it meant more power, more bloodlust, and spiteful revenge against the whites. But for Kenya’s white colonists, the people the British Empire were about to abandon, it meant uncertainty, fear, and ultimately terror. They knew it was only a matter of time.

The book’s main character, Brian Dermott, is a safari guide and expert hunter who is feeling the pinch. Half a dozen years prior he had participated in the suppression of the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya. He was known for his ruthless efficiency at killing black terrorists – the same ones who had murdered his uncle and disfigured his sister. He received a medal from the Queen for his efforts. He knows, however, that the inevitable black rule will eradicate his livelihood, as the independent blacks will surely poach, trap, and slaughter their way through the game reserves. It will also earn him quite a few enemies, since many of the new black leaders chomping at the bit for power remember his role in the rebellion’s brutal suppression and have put him on an extermination list. He’s turned back to alcohol, even though he knows it will eventually kill him; the last time he went on a bender, it put him in a coma. He probably won’t survive another, the doctors tell him.

But he loves Africa. While what’s left of his extended family operates a large and successful farm, he prefers the hunt. He loves the animals. He loves the wild. He’s the restless white man, living like it’s still the first day on Earth:

No — Brian would come back to the farm if they ever really needed him, but right now he thought he’d be happier roving with old Kidogo on a reserve, living out of a tent or in a cane-thatched banda. He had seen a lot of scraggily parched goat country in Somalia and Ethiopia, and his eyes were hungry for Kilimanjaro in the early morning; thirsty for Kerinyagga with her shining necklace of cloud. He wanted to see some broad golden plains and deep green swamps and some lazy yawning lions and some migrating zebra. The Parks money wasn’t much, he knew, but he didn’t need much money.

Yes, and when he gets a snakebite on his calf, he pours gunpowder on the wound and sets it alight to kill the poison.

You can buy Spencer Quinn’s novel White Like You here.

And who is old Kidogo? Think Natty Bumppo and Chingachgook, the spiritual handclasp between white and non-white, the forgotten and tenuous connection between civilization and savagery, with each being, in Ruark’s words, the “involuntary conscience” of the other. Kidogo is Brian’s wog, always by his side, on Safari in Nairobi, crushing the Mau Mau with gun, knife, rope, fire — whatever it took. He was there when a teenaged Brian killed his first man.

Maybe a third of their dialogue includes some Swahili. He’s the rare kind of black: utterly incorruptible, farsighted in his wild milieu, and knowing the unimpeachable value of white men who are honest, hard-working, and absolutely brutal when they need to be. He refers to Brian as Bwana, or master. In jest, Brian will refer to Kidogo by something blatantly racist, but in truth holds great tenderness for the misplaced old forest hunter. When in the bush, conferring about the movement of elephants or an unseen leopard preparing to spring a trap, Brian will sometimes show deference to the ancient aboriginal and call him baba, or father.

I apologize for another lengthy quote, but with prose like this, how can I resist?

Kidogo was in truth a wild man. He was of the Wandrobo, the forest people, the detribalized hunters, bee-chasers, poachers, honey-thieves, elephant-eaters. He was probably a Sambruru, mainly, with some infusion of Turkana, although he called himself a Nandi for some reason best known to himself, and he had probably forgotten his true name, he had been called Kidogo — meaning “little” — for so long. He didn’t know what he was, but Brian thought Kidogo was the best all-purpose gunbearer alive. He had been Brian’s dead father’s man, and with his great, outjutting heel and fingering toes, he could walk up a tree like a baboon.

Ruark’s prose can only be described as gloriously masculine. It is littered with Swahili and a multitude of African words and expressions too obscure for me to identify. The book would have been served well by a glossary, but still, the reader can cope. Contemporary, real-life events and personages large and small appear everywhere – so in this sense, Uhuru is specific to the 1950s. Of course, famous Africans such as Jomo Kenyatta and James Gichuru receive great attention in the text and dialogue, but so do forgotten figures such as Peter Poole, the first white man in Kenya sentenced by a white jury to hang for killing a black.

Ruark’s fiction is also very much travelogue, and he presents the game reserve and other areas in ferocious, resplendent detail, from buzzards gorging on the blood-soaked remains of disemboweled zebras entrenched in their own hastily-expelled feces to an array of flowers — jacarandas, bougainvillaea, frangipanni, and others — adding their delicate purples, pinks, whites, and reds to the beauty of God’s design in His cruelest corner. Ruark also trots out archaic, near-archaic (or at least very British) English idioms like he’s pulling coins out of his jingling pocket for local urchins. My favorites: describing the Second World War as the pithy “bash at the Boche” and the expression “Bob’s your uncle,” even though I don’t have an uncle named Bob.

But as one can tell from the quote about Kidogo above, Robert Ruark’s prose most importantly has no cultural filter. Either he was oblivious to what passed for political correctness in 1962 or he was too much of a man’s man to care. Brian and the other white characters bluntly discuss the inferior intelligence of blacks and their penchant for violence and superstition. It’s common knowledge that such people would be perfectly useless on a farm without white leadership and instruction. African negroes are commonly referred to in the dialogue and narration as “niggers,” “nigs,” “wogs,” “chimps,” “apes ,” “mickey mice” (yeah, that one surprised me), and many other demeaning epithets. The whites, especially the men — and especially Brian — loathe those blacks who abandon their tribal traditions to emulate whites like vindictive children. If it were up to Brian, he’d exterminate all such “townies” and keep the savages “properly savage.” He also has no illusions about the millions of Africans who behave like barbaric thugs and warlords for their own immediate gain, or just because, as they have done for millennia.

To remove any doubt in the mind of a skeptical American white woman, he relays the true story of Arundel Gray Leakey, a British citizen of Kenya as well as stalwart friend and honorary member of the Kikuyu tribe. During the Mau Mau disturbance, these very same Kikuyu stabbed his wife to death, abducted him, and buried him alive. Leakey loved the Kikuyu, could speak their language, and dedicated his life to their welfare. He also trusted them, and never carried a gun. Ruark presents this information using contemporaneous newspaper articles, which is quite a bit more than what we can find today on Wikipedia.

Yes, Brian Dermott has killed — but wogs kill much, much more.

The brutality in Africa is never-ending, and Ruark’s portrayal of blacks in their primitive element is as revolting as it true:

He supposed he liked natives, but he couldn’t stand it the way they were with animals. They had no conscious feeling of cruelty, evidently. An animal was an animal. He had seen them slowly break each major bone of a goat as they repeated the oath: If I lie may this oath kill me and my bones be broken as I break the bones of this goat. He had seen sheep and goats disemboweled while alive, and sewn up again after various things had been taken out and put in. He had seen them tear the eyes out as part of the sacrifice, and skewer them on kai-apple thorns. He had seen them catch birds and blind them with thorns spiked through the eyes, laughing as the bird fluttered wildly. They always laughed; it was a big joke to see something hurt or crippled.

They had no feeling for animals — none at all. An animal had no sensibilities. And they carried the same callous cruelty to people if the people were at all outside a circle of friendship or family.

This plot summary reveals a slight imbalance in Ruark’s vision given that the story is mainly Brian Dermott’s, yet Ruark decided to make Uhuru an ensemble piece with at least eight other important characters. Some we revisit often, others not. Perhaps with the exception of Brian’s elderly Aunt Charlotte, his women also tend to be a shade less three-dimensional than the men. At times, I found it breathlessly hard to pull away from Brian and Kidogo, because each chapter presents the subjective perspective of an individual protagonist or antagonist. Sometimes I found the transitions jarring. Regardless, I managed, and soon enough became enraptured in the revelations of Ruark’s narrative.

You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s novel Charity’s Blade here.

As Brian develops a love interest while on safari with Kate Crane, the aforementioned skeptical American woman, an ambitious and highly charismatic black politician, Matthew Kamau, schemes to take back white farmland through acts of intimidation and terror. His victim is Brian’s close friend Don Bruce, whose thriving farm is subjected to bizarre acts of ritual murder and animal torture. The black farmhands are getting skittish and his wife wants to leave Kenya for their ancestral home in Scotland. He has four small children, and so has little choice.

Meanwhile, Brian’s Aunt Charlotte, who runs an even larger farm, is trying to adapt to the inevitable uhuru. Her plan is to develop a black middle class in Kenya by offering hundreds of families ten-acre holdings on her farm. Each family will then act as sharecroppers, using the land for their own purposes as well as turning out crops such as sisal, pyrethium, and tea from which it could take more than three years to get a yield. By then, the blacks would have to option to own the land, which, she points out, would be better for them. Charlotte hopes that other big planters will follow her lead. After uhuru, she believes, a stable middle class of blacks will ensure that moderate, cooperative blacks will be able to run the country.

Upon hearing this, Brian offers this stunning rebuke — and it is a rebuke of whites as well blacks. Pure genius:

The simple truth is that none of you — us — white settlers gave a good goddamn about the plight of the poor native, or cared a snap for his future. Not until we got scared. . . .

You can’t shoot your way out of it any more so now you want to smarm your way out of it with a lot of wild agricultural schemes and plots and plans to uplift the poor bloody savage, after kicking him in the arse for the last fifty years! Well, I’ll tell you, it’s too late! The Wog has got his own dear government and the whole wide world behind him now, and he doesn’t want your sympathy or your help! All he wants is your land and your houses and your women! He wants your booze and your motorcars and your fine clothes and most of all he wants to be a bwana and shout “Boy!” at the top of his lungs! And you benevolent old-world nigger-loving bwanas will be driven into the sea or legislated out of your lands and the country will chew at itself until it’s in such a foul mess not even the bloody Russians’ll want it!

Second to Brian in narrative importance is the prominent black attorney Stephen Ndegwa. Ndegwa is part of Kamau’s coalition but is much more moderate and reasonable, and secretly opposes Kamau’s plans for immediate retribution. He also lacks Kamau’s exploitive contempt for whites — especially white women, whom Kamau disgustingly sees as little more than ravenous sex objects whenever he’s abroad. Ndegwa wants uhuru, but unlike the headstrong Kamau, understands the challenges that will accompany it. He fears these challenges because he knows the manifest limitations of his own people. He also understands the horrid plight the people of Kenya will be in if they set themselves at odds with the whites.

But Ndegwa is no token. He’s disillusioned with his own decadent, white ways. He has two traditional wives in the village and a nearly-white trophy wife in a big house in Nairobi whom he barely speaks to anymore. He mourns the loss of his people’s traditions. He mourns how young black men no longer tend to their families, livestock, and property, and instead adopt ill-fitting white pretensions or go off on stupid and self-destructive Mau Mau adventures. He lost two sons that way. And he especially regrets the abandonment of female circumcision, which has done more to devalue black women and the traditional black family than anything else.

What?

Yes, Robert Ruark’s Uhuru makes us rethink female circumcision — not for Western women, of course, but for African women. According to Mr. Ndegwa, circumcision makes them easier to control and more dedicated to their families. It gives them value for potential husbands, since these husbands will know a particular bride will be less inclined to betray him sexually. By 1960, this value has largely been lost. Without circumcision, thousands of young black women now either betray their husbands or head to the towns to become whores.

Here’s one described trenchantly by Ruark; see if you are at all tempted:

And if you were so minded and had plenty of penicillin, the services of the hipswinging Somali whore with the kohl-smudgy eyelids who ogled you from a starting point somewhere between the noseless leper and the orange-bearded Hadj who wore the henna in his whiskers as a sign that he had been to Mecca and had kissed the sacred Kaaba stone.

Ndegwa professes no answer to the distaff conundrum plaguing his people and remains stuck, like many of us, between cruel solutions and horrible outcomes. What are you gonna do?

The plot ultimately resolves — perhaps not as neatly as I would like, but I’ll take it. I will tell you about none of it except for what you can probably piece together yourself from this review. Stephen Ndegwa attempts to help make Aunt Charlotte’s scheme a reality. Matthew Kamau and his thuggish minions try to get in the way. A few good things happen. Something really bad happens. A few more really bad things happen. Brian, on a downward slide in his now-lethal alcoholism, does something utterly righteous. More or less in that order. The end.

For me, Uhuru is one of those before-and-after novels. After experiencing the abundance of the language, the sweep of the scenery, the distinctiveness of the characters, the relentlessness of the plot, the sledgehammer insights into racial matters, and the direct presentation of truth truth truth at its ugliest and at its most sublime — both of Man and Nature — it will be impossible to forget Uhuru.

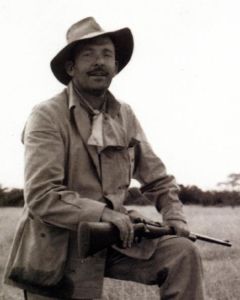

In closing, a few words about the author. Robert Ruark’s Wikipedia page is serviceable, yet brief. Ruark was very well-known in his prime, but today of course is little remembered. In the 1940s and 1950s, he was known mostly for his humorous novels and outdoor magazine articles about hunting, world travel, and guns. The novels Something of Value, Poor No More, and Uhuru were bestsellers, with Something of Value being adapted into a successful film in 1957 starring Sidney Poitier. He wrote 11 novels and two non-fiction books which were published posthumously. He died in 1965 at age 49 of cirrhosis of the liver after a lifetime of alcoholism. In his day, he corresponded with Ernest Hemingway, Richard Nixon, and J. Edgar Hoover.

Although Uhuru lacks its own Wikipedia page, Ruark’s offers the following telling anecdote:

The book apparently libelled [sic] some politicians in Kenya, and while he [Ruark] was in Nairobi after its publication, Kenya, staying at the New Stanley Hotel, his arrest was ordered. Before he could be arrested, however, he was tipped off, and he apparently fled overnight to South Africa by air.

Aside from three biographies that were originally published between 1992 and 2008, a hopefully still-extant literary society, and an inn named after him in Southport, North Carolina, Robert Ruark is mostly remembered these days only by aging gun and hunting enthusiasts, if the internet is any indication. Kim du Toit, who immigrated to the United States from South Africa as an adult, lists Uhuru as one of his favorite novels. He avers in this post that Ruark really “got Africa” and that Ruark had coined the cynical term which du Toit uses all the time: “Africa wins again.”

There is little else. I found almost no critical assessments of Uhuru using various search engines, although I am sure a good university library would contain quite a bit in its archives. I picked up Uhuru in a used bookshop a decade ago on a whim, having never heard of Ruark. I’m happy that I have finally read him, and I hope this review will help spark renewed interest in this nearly-forgotten author.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Whither Thou Goest, Diaspora?

-

Get to Know Your Friendly Neighborhood Habsburg

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Thank You, O. J. Simpson

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

7 comments

This book planted the seeds of doubt that grew into heresy against the orthodoxy preached by Ashley Montague: Congo Kitabu by Jean-Pierre Hallet.

So of course I had to go online and find a copy.

I am so grateful for the books that SJQ (and Kathryn S, too) brings to my attention here at CC.

And I am grateful for your feedback. I hope you enjoy the book.

As a precocious pre-teen, the Book of the Month Club was happy to send me his follow-up, The Honey Badger. It’s a hard-hitting tale of the usual ruthless, drunken, two-fisted … writer, a la Hemingway (and Ruark, apparently), who boozes, belts and beds his way through life. Women play the role of Africans here; disposable, stupid, ruthless, will rip your balls off at any moment (hence the title; the Dutch translation is apparently “The Vampires”), thus to be feared and respected if only as deadly enemies. Probably not a good book to put in the hands of a pre-teen. Perhaps enjoyable today, less in a “good old days” than in a “wow, men really were drunken pigs in the 60s” way. Good solid prose, though. I must check out this Uhuru.

Please let me know what you think about it.

I vividly remember this book in my parents’ bookcase, but I always assumed it was some anti-civilizational tripe and never picked it up. Now I wish I had foregone a Doc Savage and read the work. Thank you so much for bringing this book to our attention!

P.S. I received a copy of “Solzhenitsyn and the Right” a few days ago in the post, and I am about halfway through. Bravo!

Thank you, Karl! I am thrilled you’re enjoying it.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment