Africa. Poor, poor little Africa. See its starvation, poverty, and misery on TV. Don’t you feel sorry for it? Don’t you want to pick it up, kiss it, and make it feel better even as it wets on your hands? Of course you do. Aren’t you a good lemming? Don’t you like to roll over and beg when it’s expected of you? Or even better, give Africa lots of money? Or better still, to give it your heart and soul, clap your hands, and believe in it?

Yeah, me neither. But the film The Constant Gardner was about the treacly stuff, based on a John le Carre novel where Justin (Ralph Fiennes) goes to Africa to do good, taking Tessa (Rachel Weisz) with him, an activist wife who also does good, and winds up banging one of the locals because the local is such a caring man, so deep and profound. . .

Critics talked of the beauty of Africa captured on camera. I assume they meant the wildlife bits, or maybe not. Maybe they meant modern urban life, trains packed to the gills with people riding on top of cars, and tin hut slums. A quartet of Africans doing a doo-wop, urging a crowd to practice safe sex (no need to encourage Africans to practice sex — least of their problems).

The film dealt with evil corporations dumping bad pharmaceuticals on Africa, but to me, the real evil is when Tessa, having Justin’s child, takes her sick baby to a hospital. Her African boyfriend shames her for wanting to go to a Western hospital instead of an African one. “So you think we’re inferior?” he accuses. She goes to an African hospital, a slum with four walls around it, and her baby dies there. That was when I lost what little sympathy I had for Tessa or Justin.

But the film stepped over this to get back to the real moral dilemma: big pharma. A pity there wasn’t a walk-on part for Bill Gates and his amazing vaccines, but of course, it’s conservative big pharma we want to skewer.

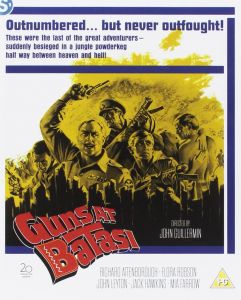

A better African movie expresses the white man’s dilemma, if not his burden. That is Guns at Batasi, a 1964 film made, appropriately, in black and white.

It portrays Sergeant-Major Lauderdale, admirably played by Richard Attenborough, a tough RSM (Regimental Sergeant Major for you non-Brits) of the old school, serving in a colonial African nation that has just become independent. Lauderdale and his fellow NCOs are now “advisors” to the country’s new army. The sergeants are a collection of types whose nicknames define them: “Muscles” is the PT instructor, “Schoolie” the education NCO, “Digger,” “Dodger,” and so on. Lauderdale runs a tight ship. In this colonial world, when he drinks (never to excess), decorum is strictly observed, and HRH’s portrait is above the bar.

This world is receiving a modern canker: Miss Barker-Wise, a Member of Parliament played with acerbic tartness by Flora Robson.

Miss Barker-Wise has an immediate contempt for the British Army, feeling they hold newly liberated Africans in disdain. Lauderdale is cool towards her, and during a mess ceremony, she scratches her ass while everyone is at attention.

Also at the dinner is Karen Ericksson, Mia Farrow’s screen debut. Karen, a UN secretary, was trapped when the airport closed along with Charlie Wilkes (John Leyton), a new private, on his way out of the army.

You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here.

Miss Barker-Wise’s contempt for the British military and the White Man’s Burden is countered by her warm fondness for Lieutenant Boniface (Errol John), a black officer she mentored back in England and sponsored at university. She can’t wait for the Africans to show their true greatness.

She carps about imperialism. Lauderdale shrugs this off, saying he’s had enough talk of her “harmless little Africans.” Barker-Wise shoots back that “his type” is outdated, and doesn’t see how good and clever blacks really are.

Lauderdale is brusque. “The best of theirs is as good as the best of ours,” he says, “and the worst is as bad as ours. . . and ours are pretty bad.”

When she berates the harmful militarist attitude of Lauderdale, he counters like a British John Wayne: “If it wasn’t for us, you wouldn’t be able to go around spouting your silly, half-baked ideas.”

Battle lines are drawn. A budding romance begins with Wilkes and Karen. Meanwhile, the tribes in this country are at odds, and Boniface joins a coup, demanding Captain Abraham, the black CO, surrender. He refuses. Boniface arrests Abraham and takes over, his fellow rebels ready to dispense with the British-approved government and put in a jailed politician as president.

In the nation’s capital, the British community hunkers down to wait it out. Colonel Deal (Jack Hawkins), the British chief advisor, demands the government return to order. The British ambassador reminds Deal that it isn’t a white man’s country anymore. In a foretaste to Mandela, the ambassador shrugs that in the new Africa, going to jail is a shortcut to power. Hawkins blusters, but he has to wait until the tantrum is over.

At Batasi, Lauderdale is shocked and angry. He doesn’t want Boniface to get away with mutiny, nor his men confined to the NCO club, watched by the troops they’ve been advising. A wounded Abraham stumbles into the club, protected by Lauderdale. Lauderdale takes his sergeants and they raid the arsenal for weapons.

Barker-Wise complains that Lauderdale is exacerbating the situation. Lauderdale replies: “Thought you believed in equality? Well, they have guns and we don’t. That’s not very equal, is it?”

Barker-Wise is disturbed by the shooting and urges Boniface to do things the proper, democratic way — or at least be more circumspect in his use of machtpolitik. Now it’s Boniface’s turn to talk. He denounces Barker-Wise and her “democracy.” “No one,” he says, “talks better than the British. They drug you with their talk.” Africa will solve its own problems its way.

He put up with being at university in England in order to get power, and nothing more. No more talk, he lectures her. . . now, the white man and woman will listen. Boniface has a real future with BLM.

A chastened Barker-Wise is kept under guard by Boniface, who demands Lauderdale surrender his arms and Captain Abraham or face the mess being blown apart by the unit’s Bofors guns. Lauderdale plans to put the guns out of action, but his fellow sergeants balk. They don’t want to be involved, since it’s against orders. It’s not their fight. Lauderdale is outraged, but he can’t order them. He puts on battledress and will do the job himself. Wilkes signs on. After all, he’s a soldier and joined up for action, and might as well do a bit of glory before he’s demobbed.

Lauderdale and Wilkes easily sneak past the African troops. The Bofors guns are exploded just as Deal arrives to announce the new government has won and all is back to normal. Boniface is furious.

In the new “democracy,” Lt. Boniface is now a colonel, and Lauderdale is expelled from the country for interfering in its political process (trying to stop a mutiny), and, obviously, making a fool out of a black man and, we may assume, talking, not listening.

Drinking in the bar, a stunned Lauderdale lets his anger grow until he throws his glass at the Queen’s portrait. Shocked, he immediately cleans up the mess.

Regaining his composure, Lauderdale parades outside in full dress, taking one last look at Batasi before he’s packed off to England.

Batasi‘s casting is inspired, especially Attenborough. I also enjoyed the discussion of “New Africa,” its chaos and lawlessness depicted as whites react to the changes. They are like a group of King Lears, watching the Gonerils and Regans take over. The confrontations between Lauderdale and Barker-Wise are exciting, as Barker-Wise reminds me of a great many liberals, especially women, who adore anyone who’s black, and turn a blind eye to any bad (real) news about Africa. It’s a world where, as Dennis Wheatley put it in The Devil and All His Works, the adults abandoned Africa and locked themselves out of the Kindergarten to let the children play with loaded guns. At least, Wheatley chided, the West should keep its own house in order. We see the results of that hope.

Africa will always be the child in need of Western help, and Westerners seem to like it this way, dumping unrepayable loans and foreign aid on this poster child of a continent. Tom Wolfe noted this in his novel I Am Charlotte Simmons, where students eagerly go to Africa to build huts and tote native babies, because it’s where all the grant money is these days; the needed addition to the resume.

In 1964, when Guns at Batasi was made, there was still a lot of hope for Africa. It was assumed the continent was a world where a flock of Sidney Poitiers would rule wisely. It was the decade of Africa. In V. S. Naipaul’s brilliant novel A Bend in the River, one of the characters, capturing the despair of a “democracy” ruled by the “Big Man,” looks at her watch and says “the decade of Africa ended ten seconds ago.”

South Africans had a saying whenever the latest chaos sprouted north of them: Africa wins again.

The movie recalls the 1980s, when I was a security guard in Boston, and one of my fellow guards was an African student from Guinea with powerful connections to their army. He always boasted that Africa, when it found a “Great Deliverer” like Mao or Stalin, would unite his continent and take over the world. He was disdainful of the West despite his college education, luxurious apartment, and white girlfriend.

“You must remember,” he told me, “the white man tries to remake Africa in his image and fails because, my friend, Africa will always be Africa.”

He didn’t say this in the sorrow Naipaul did; he believed Africa’s destiny, nay, duty, was to overwhelm the world. He was a Muslim and Marxist, and hoped the “Great Deliverer” would meld both those creeds into a truly African faith.

I think he and Boniface would be good drinking companions until one decided to overthrow the other. Africa will always be Africa.

Guns at Batasi is a meditation on duty and collapse, and is worth viewing for this and its acting. It is good popcorn cinema. Lauderdale’s prompt action and duty are a fitting antidote to the usual guilt trips we see about the dark continent.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Is There a Right Wing after Postmodernity? “Euronormativity” and Biopoliticized Resistances to the “Counterhegemonic” Left

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Der Krieger und der Stadtstaat

-

Civil War

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 581: Fourth Meeting of the Counter-Currents Book Club — Greg Johnson’s Against Imperialism

-

“Few Out of Many Returned”: Theaters of Naval Disaster in Ancient Athens, Part 2

-

“Few Out of Many Returned”: Theaters of Naval Disaster in Ancient Athens, Part 1

6 comments

You should do a review of the movie “The Wild Geese”.

This sounds like one of those movies they couldn’t make these days, at least without pulling the screenplay inside out.

It’s a very very very good film. Nice taste.

Wild Geese? The one set in Africa with Richard Burton? I remember seeing it, and I’m not fond of doing a review. It seemed a bit Hollywood to me, and did have a lot of action, but somehow it leaves me blank, although the theme of betrayal after doing a mission should interest me, it just doesn’t. It seemed like lukewarm Burton. I’m working on another review; not in Africa, but racial.

You definitely should do a review of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”, which, I understand is being lauded in college English literature classes in this day as the best book about the terrible European colonialists and the ‘horrors’ we White colonialist perpetrated in Africa. I thought it was the most horrific novel I’d ever read, and only finished it to be able to understand what others were raving about. Horror from beginning to end, and well deserved was the phrase which originated within it — ‘the horror, the horror’ — which was later introduced to American audiences in “Apocalypse Now”, loosely based on this novel. Vietnam and Congo are still widely admired today as places that ‘defeated colonialism’, as far as I can tell, and both are still warts on civilization. The horrors in Africa were originated there, and had nothing to do with ‘colonialism’, and still do not. Even Conrad could only hint at them, much in the style of Lovecraft.

I first saw Guns at Batasi on the Late Show back when I was a lad.

At that time my ideas about Africa were pretty much shaped by movies I had seen on the Late Show, usually involving a regiment of European troops in pith helmets or Legion kepis putting down native uprisings using a combination of stiff upper lip and Maxim gun fire.

The thing that struck me about Guns was that you don’t turn an entire country over to, well, the natives and then expect it to function like a modern state. Bad show for everyone all around!

OK, later I would get a more thorough understanding of Africa, including some travel on that continent. But events since my first viewing of the movie have done very little to change my overall view. The West did turn Africa over to those natives and we have seen the predictable results in a non-stop succession of debacles. Bad show in places like Uganda and Congo, where European rule was a thin over-strata. But in places which had been settled by Europeans for centuries, like South Africa and Angola, it’s been a rollback of Western civilization in terms of borders, resources and genes.

That’s how I saw the Rhodesian Bush War and the South African Border War: as the forces of the White World maintaining civilization against great big native uprisings. Putting those conflicts in terms of “one man one vote (one time!)” made about as much sense as the British troops at Rorke’s Drift (Natal, January 1879) letting the Zulu impis vote for who would control the mission station. Who would believe a movie made on such a premise?

Yet incredibly the Western world would surrender to the Africans entire cities in Europe and North America. The resulting mayhem – car burnings, looting of big box stores, assaults on police, driveby mostly peaceful gun violence, big man rule, the summer rioting season, pillaging of the public treasury – are well understood by any veteran of the Late Show or Beitbridge Run: native uprisings. Indeed, many of the Long Hot Summer riots have been termed just that by their cadres: uprisings. Regardless of continent, Africans will be Africans.

In this stage of the struggle, we can not allow Africa to win again. It’s not about the number of ballots stuffed into boxes. It’s about duty, order and civilization.

Perhaps what White nations need today is a squad of regimental sergeants major.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment