Kevin MacDonald’s Individualism & the Western Liberal Tradition: Aristocratic Individualism

Ricardo Duchesne3,588 words

In Part 1 of my detailed examination of Kevin MacDonald’s Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition: Evolutionary Origins, History, and Prospects for the Future (2019) I covered MacDonald’s argument in chapter one that Europe’s founding peoples consisted of three population groups:

- Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) who were descendants of Upper Paleolithic peoples who arrived into Europe some 45000 years ago,

- Early Farmers (EFs) who migrated from Anatolia into Europe starting 8000 years ago, and

- Indo-Europeans (I-Es) who arrived from present-day Ukraine about 4500 years ago.

Using MacDonald’s argument, I emphasized how these three populations came to constitute the ancestral White race from which multiple European ethnic groups descended.

The task MacDonald sets for himself in chapter two is a most difficult one. He sets out to argue that the most important cultural trait of Europeans has been their individualism, that this trait was already palpable in prehistoric times among WHGs and I-Es, that it is possible to offer a biologically based explanation for the emergence of this individualism, and that this individualism was a key component of the “extraordinary success” of Europeans. How can one employ a biological approach to explain individualistic behaviors that seem to defy a basic principle of evolutionary psychology — that members of kin groups, individuals related by blood and extended family ties, are far more inclined to support their own kin, to marry and associate with individuals who are genetically close to them, than to associate with members of outgroups? It is also the case that the concept of “group selection,” to which MacDonald subscribes, says indeed that groups with strong in-group kinship relationships are more likely to be successful than groups in which kinship ties are less extended and individuals have more room to form social relations outside their kin group.

Evolutionary psychologists prefer models that explain group behavior in animals and humans generally. They also prefer to talk about cultural universals — behavioral patterns, psychological traits, and institutions that are common to all human cultures worldwide. When they encounter unusual cultural behaviors, they look to the ways in which different environmental settings may have resulted in genetically unique behaviors, or to the ways in which relatively autonomous cultural contexts may have promoted or inhibited certain common biological tendencies.

MacDonald combines these two approaches to argue that the individualism of Europeans is a genetically-based behavior that was naturally selected by the unique environmental pressures of northwest Europe. However, it is only in reference to the egalitarian individualism of northwestern hunter-gatherers, which is the subject of chapter three, that MacDonald tries to explain how this egalitarian individualism was genetically selected. He takes it as a given in chapter two that the I-Es were selected for their own type of aristocratic individualism, without linking this individualism to environmental pressures in the Pontic steppes. In Part 3 we will bring up his argument about how Europe’s egalitarian individualism was naturally selected.

Cultural Peculiarities of Indo-Europeans

MacDonald refers often to my book, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, in his analysis of the culture of Indo-Europeans, while putting a stronger and clearer emphasis on the way kinship was “de-emphasized” within the central institution of the Männerbund, or the warrior brotherhood of the I-Es. These warrior bands, as I also observed in Uniqueness, were organized primarily for warfare, which was the main way aristocrats found a livelihood consistent with their status as warriors, opportunities to accumulate resources and followers, and a chance to attain heroic renown among peers. Membership was open to any aristocratic warrior willing to enter into a contractual agreement with the leader of a warband, with the greatest spoils and influence going to those who exhibited the greatest military talents. In other words, these warbands were open to individuals on the basis of talent, rather than “on the basis of closeness of kinship.”

My emphasis in Uniqueness was less on the looser kinship ties of I-Es than on the “aristocratic egalitarianism” that characterized the contractual ties between warriors — how the leader, even when he was seen as a king, was “first among equals” rather than a despotic ruler. MacDonald emphasizes both this aristocratic trait and the ways in which I-Es established social relations outside kinship ties.

I-Es were aristocratic in the true sense of the word: Men who gained their reputation through the performance of honorable deeds, proud of their freedom and unwilling to act in a subservient manner in front of any ruler. In addition to, or as part of the Männerbund, “guest-host relationships (beyond kinship) where everyone had mutual obligations of hospitality,” and where “outsiders could be incorporated as individuals with rights and protections” were common among these aristocrats. By the time the Yamnaya migrated into Europe some 4500 years ago, they had developed a highly mobile pastoral economy coupled with the riding of horses and the development of wagons, in the same vein as they initiated a “secondary products revolution” in which animals were used in multiple ways beyond plain farming; for meat, dairy products, leather, transport, and riding. This diet, together with the open steppe environment, where multiple peoples competed intensively to support a pastoral economy requiring large expanses of land, encouraged a highly militaristic culture. Indo-Europeans became a most successful expansionary people: Currently, 46% of the world’s population speaks an Indo-European language as a first language, which is the highest proportion of any language family.

Egtved Girl wears a well-preserved woollen outfit and a bronze belt plate which symbolises the sun — a well-travelled woman at the dawn of the Celtic Urnfield culture who found herself visiting Denmark.

MacDonald could have clarified for readers unfamiliar with evolutionary theories of marriage and family that when he writes about “an aristocratic elite not bound by kinship,” or about how ties between aristocrats “transcended the kinship group,” he is not denying the importance of blood ties between extended I-E family members and extended I-E families grouped into clans. He observes that marriages occurred within clans and that punishments and other disputes were decided in terms of kinship customs. The difference is that I-Es developed social ties above their kin relations that “tended to break down strong kinship bonds.” While the strong kinship cultures of the East were characterized by arranged marriages within the extended family, and political-military ties were heavily infused by kin customary relations, among the Corded Ware culture that grew out of the Yamnaya one finds exogamy or marriage outside the extended family or with females “non-local in origin,” including the practice of monogamy. Exogamous marriages between I-E groupings, including the peoples they dominated, were a key component of their guest-host networks and a means to pull together military alliances and integrate new talent.

Individualism and Ethnocentrism Among Ancient Greeks

But it could be that MacDonald does assume that, in the degree to which Europeans created social ties outside kinship ties, it would have been inconsistent for them to retain kinship affinities and ethnocentric tendencies. He observes that “despite the individualism of the ancient Greeks, they also displayed [in their city-states] a greater tendency toward exclusionary (ethnocentric) tendencies than the Romans or the Germanic groups that came to dominate Europe after the fall of the Western Empire.” (p. 48)

The Greeks had a strong sense of belonging to a particular city-state, and this belonging was rooted in a sense of common ethnicity. . . The polis was thus. . . exclusionary (serving only citizens, typically defined by blood) . . . Greek patriotism based on religious beliefs and a sense of blood kinship was in practice very much focused on the individual city, making those interests absolutely supreme, with little consideration for imperial subjects, allies, or fellow Greeks in general. (p. 48-49)

I don’t think it should surprise us that despite their individualism the Greeks had a conception of citizenship defined by kinship. I would argue, rather, that it was precisely their individualistic detachment from narrow clannish ties that allowed the Greeks to develop a new, wider, and more effective form of collective ethnic identity at the level of the city-state. Citizenship politics was introduced in Greece in the seventh century BC as a challenge to the divisive clan and tribal identities of the past. A citizen in a Greek city-state was an adult male resident individual with free status, able to vote, hold public office, and own property. Bringing unity of purpose among city residents, a general will to action to communities long divided along class and kinship lines, was the aim behind the identification of all free males as equal members of the city-state.

As I argued in “The Greek-Roman Invention of Civic Identity Versus the Current Demotion of European Ethnicity:”

We should praise the ancient Greeks for being the first historical people to invent the abstract concept of citizenship, a civic identity not dependent on birth, wealth, or tribal kinship, but based on laws common to all citizens. The Greeks were the first Westerners to be politically self-conscious in separating the principles of state organization and political discourse from those of kinship organization, religious affairs, and the interests of kings or particular aristocratic elites. The concept of citizenship transcended any one class but referred equally to all the free members of a city-state. This does not mean the Greeks promoted a concept of civic identity regardless of their lineage and ethnic origin […] The Greeks…retained a strong sense of being a people with shared bloodlines as well as shared culture, language, mythology, ancestors, and traditional texts.

City-states were indispensable to forge a stronger unity among city residents away from the endless squabbling of clannish aristocratic men, for the sake of harmony, the “middle” good order. To this end, the ancient Greeks enforced a set of laws (nomoi) that applied equally to all citizens, de-emphasizing both kinship ties and differences between classes — which brings me to another point I may elaborate in more detail in another post: The aristocratic individualism of I-Es contained a democratizing impulse.

In the creation of city-states and the subsequent democratization of these polities, particularly in Athens, we see an egalitarian impulse emerging out of the aristocratic war band and the prior aristocratic governments of ancient Greece when a council of aristocratic elders, without input from the lower classes, was in charge. It is not that the old aristocratic values were devalued; rather, these values trickled downwards to some degree. The defense of the city, and warfare generally, would no longer be reserved for privileged aristocrats but would become the responsibility of hoplite armies manned by free farmers. Heroic excellence in warfare would no longer consist of the individual feats of aristocrats but in the capacity of individual hoplites to fight in unison and never abandon their comrades in arms.

Solon

The democratization of the city-states from Solon (b. 630 BC) to Cleisthenes (b. 570 BC) to Pericles (495–429 BC), the creation of popular assemblies, were associated with the adoption of hoplite warfare, starting in the mid-seventh century, the abolition of debt slavery, the securing of property rights by small landowners, and the creation of an all-embracing legal code. This unity of purpose was taken to its logical conclusion in the ideal city-state imagined by the character of Socrates in Plato’s Republic, “Our aim in founding the city was not to give especial happiness to one class, but as far as possible to the city as a whole.”

Individualism and Ethnocentrism Among Romans

The ethnocentrism of the Greeks beyond their city-states should also be recognized. The ancient Greeks came to envision themselves as part of a wider Panhellenic world in which they perceived themselves as ethnically distinct precisely in lieu of their individualistic spirit, which they consciously contrasted to the “slavish” spirit of the Asians. As Lynette Mitchell observes in Panhellenism and the Barbarian in Archaic and Classical Greece (2007), “there was in antiquity a sense of Panhellenism.” Panhellenism was “closely associated with Greek identity.” While this unity was ideological, rather than politically actual, weakened by endless quarrels between city-states, the Greeks contrasted their citizen politics with the despotic government of the Persians.

Europeans, however, would have to wait for the Romans to start witnessing a strong common identity beyond the city.

The same pattern from an aristocratic form of rule towards citizenship politics was replicated in Roman Italy, followed by the creation of an actual, and more encompassing, form of collective identity. MacDonald analyzes very effectively how the aristocratic individualist ethos of Indo-Europeans shaped the course and structure of politics throughout the Roman Republican era in an Appendix to Chapter 2. Even though an individualist ethos prevailed in Rome, we should not be surprised by the observation that, for the early Romans, “family was everything” and that “affection and charity were. . . restricted within the boundaries of the family.” We should not be surprised either that “there were also wider groupings” shaped by strong kinship ties, and that “cities developed when several of these larger groupings (tribes) came together and established common worship,” and that Roman cities were not “associations of individuals,” which is a modern phenomenon.

We must look for this aristocratic individualist ethos in the “non-despotic government” the Romans created, their republican institutions. This was a government in which aristocratic patrician families contested and shared power in the senate, which would eventually expand to include representative bodies, tribunes, for non-aristocratic plebeians with wealth, towards a separation of powers, between the senate of the patricians and the tribunes of the plebs, along with two consults from each body elected with executive power. The I-E aptitude for openness and social mobility was reflected in the rise of plebeian tribunes and the eventual acceptance of marriage between patricians and plebs. It was also reflected in the gradual incorporation of non-Romans, or Italians, into Roman political institutions. As MacDonald writes,

Instead of completely destroying the elites of conquered peoples, Rome often absorbed them, granting them at first partial, and later full, citizenship. The result was to bind ‘the diverse Italian peoples into a single nation.'” (p. 80)

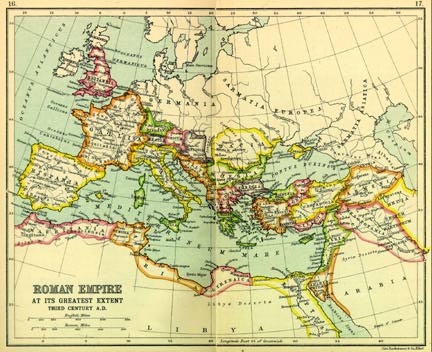

Unlike the Greeks, who restricted citizenship to free-born city inhabitants, the Romans extended their citizenship across the Italian peninsula, after the Social War (91–88 BC), and across the Empire, when the entire free population of the Empire was granted citizenship in AD 212. MacDonald believes that this openness beyond Rome and beyond Italian ethnicity “resulted in Rome losing its ethnic homogeneity.” (p. 84) He cites Tenney Frank’s argument (1916) that Rome’s decline was a product of losing its vital racial identity as Italians become mixed with very heavy doses of “Oriental blood in their veins.” He believes that the Roman I-E strategy of incorporating talent into their groupings worked so long as “the incorporated peoples were closely related to the original founding stock.”

I am not sure if by “closely related” MacDonald means only the Latins; in any case, I see the forging of all Italians “into a single nation” as a very successful group evolutionary strategy in Rome’s expansionary drive against intense competition from multiple cultures and civilizations in the Mediterranean world. Similarly to the Greeks, the Roman-Italians retained a very strong sense of ethnic national identity throughout their history.

It is important to keep in mind that Italian citizenship came very late in Roman history, some five centuries after Rome began to rise. We should avoid conceding any points to the erroneous and politically motivated claim by multiculturalists that the Roman Empire was a legally sanctioned “multiracial state” after citizenship was granted to free citizens in the Empire. This is another common trope used by cultural Marxists to create an image of the West as a civilization long working towards the creation of a universal race-mixed humanity. Philippe Nemo, under a chapter titled “Invention of Universal Law in the Multiethnic Roman State,” wants us to think that “the Romans revolutionized our understanding of man and the human person” in promulgating citizenship regardless of ethnicity. But I agree with the Israeli nationalist Azar Gat that ethnicity remained a very important marker for ancient empires generally, no less an important component of their makeup than domination by social elites over a tax-paying peasantry or slave force. “Almost universally they were either overtly or tacitly the empires of a particular people or ethnos.”

It should be added that Romans/Latins were so reluctant to grant citizenship to outsiders that it took a full-scale civil war, the Social War, for them to do so, even though Italians generally had long been fighting on their side helping them create the empire. Gat neglects to mention that all the residents of Italy (except the Etruscans, whose status as an Indo-European people remains uncertain) were members of the European genetic family. Let’s not forget how late in Rome’s history, AD 212, the free population of the empire was given citizenship status, and that the acquisition of citizenship came in graduated levels with promises of further rights with increased assimilation. Right until the end, not all citizens had the same rights, with Romans and Italians generally enjoying a higher status.

Moreover, as Gat recognizes, Romanization was largely successful in the Western half of the empire, in Italy, Gaul, and Iberia, all of which were Indo-European in race, whereas the Eastern Empire consisted of an upper Hellenistic crust combined with a mass of Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Judaic, Persian, and Assyrian peoples following their ancient ways, virtually untouched by Roman culture. The process of Romanization and expansion of citizenship was effective only in the Western (Indo-European) half of the Empire, where the inhabitants were White; whereas in the East it had superficial effects, although the Jews who promoted Christianity were “Hellenistic” Jews. This is the conclusion reached in Warwick Ball’s book, Rome in the East (2000). Roman rule in the regions of Syria, Jordan, and northern Iraq was “a story of the East more than of the West.” Similarly, George Mousourakis writes of “a single nation and uniform culture” developing only in the Italian Peninsula as a result of the extension of citizenship, or the Romanization of Italian residents. Perhaps we can also question Tenney Frank’s argument about the heavy presence of Oriental blood in Italy. According to David Noy, free overseas immigrants in Rome — never mind the Italian peninsula at large — might have made up 5% of the population at the height of the empire, which is to deny Orientalist elements among the enslaved population.

For these reasons, I would hesitate to say that the I-E strategy of openness dissolved the natural ethnocentrism of Italians and Europeans generally. Their aristocratic individualism should be seen as a more efficient and rational ethnocentric strategy re-directed towards a higher level of national and racial unity, without diluting in-group feelings at the family level. It was only at the level of clans and tribes that the Greeks and the Romans diluted in-group kinship tendencies when it came to the conduct of political affairs. In Rome, the Senate worked as a political body mediating the influence of families in politics, not eliminating kinship patron-client relations at the level of families, but minimizing their impact at the level of politics. The Senate was a political institution within which elected members (backed by their extended families and patron-client connections) acted in the name of Rome even as they competed intensively with each other for the spoils of office holding.

It has indeed become clearer to me, after thinking about MacDonald’s contrast between kinship oriented and individualist cultures, why the East was entrapped to despotic forms of government. Rather than viewing this government as a purely ideological choice, it can be argued that the prevalence of despotism in the East was due to the prevalence of kinship ties in the running of governments and the consequent inability of Eastern elites to think about higher forms of identity in the way the Greeks and Romans did. Eastern empires were highly nepotistic, with rulers using the state to expand their kinship networks, favoring relatives while behaving in a predatory way against rival ethnic-tribal groups, without a sense of city-state or national unity, and without the ability to generate loyalty among inhabitants or members belonging to other kinship groups. The historian Jacob Burckhardt once observed about the Muslim caliphates that “despite an occasionally very lively feeling for one’s home region which attaches to localities and customs, there is an utter lack of patriotism, i.e., enthusiasm for the totality of a people or a state (there is not even a word for ‘patriotism'”). Burckhardt does not say anything about kinship, but it seems reasonable to infer that the strong kinship ties that prevailed in the East made it very difficult to forge a common identity beyond these ties.

What ultimately allowed the Romans to defeat the Semitic Carthaginian empire, thereby securing the continuation of Western civilization, was their ability, in the words of Victor Davis Hanson, to “improve upon the Greek ideal of civic government through its unique idea of nationhood and its attendant corollary of allowing autonomy to its Latin-speaking allies, with both full and partial citizenship to residents of other Italian communities.” This form of civic identity among Italians was the main reason Rome was able, as MacDonald observes, “to command 730,000 infantry and 72,7000 cavalrymen when it entered the First Punic War” and to sustain major defeats in the early stages of the Second Punic War without losing the loyalty of its Italian allies and the ability to marshal huge armies.

The individualism of Europeans should not be seen as an automatic impediment to ethnocentric unity. It should be seen as a means to forge higher national unities. It is no accident that Europe would eventually give birth to the formation of the most powerful nation-states in the world, capable of fighting ferociously with each other while dominating the disorganized, clannish, despotic non-White world.

Notes

This article originally appeared on the Council for European Canadians website on February 18, 2020.

Kevin%20MacDonaldand%238217%3Bs%20Individualism%20and%23038%3B%20the%20Western%20Liberal%20Tradition%3A%20Aristocratic%20Individualism

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Get to Know Your Friendly Neighborhood Habsburg

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Geheime Aristokratien

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

15 comments

Duchesne’s development of MacDonald’s point about the expansion of Roman citizenship beyond ethnic ties serving to weaken Rome should go a long way toward blunting the often-made claim that Rome provides us with an example of a successful multicultural/multiracial society. Thus, Rome is NOT a counterexample to the ethnonationalist’s contentions.

Also, the point still stands that the Greeks developed a pan-hellenic consciousness beyond membership in the polis. This spirit emerged during the Persian wars. That sense of a common identity helped the Greeks to defeat the invading Persians and ushered in the Golden Age of classical antiquity.

The ancient Greeks had a pan-Hellenic consciousness during the war against Troy. The warrior aristocrats from across Greece banded together as essentially one army to overcome Troy.

i think you are on point democracy and individualism was born because all aryan men were free

here an interesting reference from david anthony

According to studies of IndoEuropean mythology, young Yamnaya men would go off in warlike groups, to conquer other terriotories and their womans for a few years, then return to their village and settle down into respectability as adults. Those cults were mythologically associated with wolves and dogs, like youths forming wild hunting packs, and the youths are said to have worn dog or wolf skins during their initiation . He says it’s easy to imagine groups sacrificing and consuming the animals as a way to symbolically become wolves or dogs themselves. Anthony (an expert of indo european history) says that all this offers solid archaeological evidence for the youthful “wolf packs” of Indo-European legends – and sees a link to the myth of the foundation of Rome. “You’ve got two boys, Romulus and Remus, and a wolf that more or less gives birth to them,” he says. “And the earliest legends of the foundation of Rome are connected with a large group of homeless young men who were given shelter by Romulus. But they then wanted wives, so they invited in a neighbouring tribe and stole all their women. You can see that whole set of early legends as being connected possibly with the foundation of Rome by youthful war bands.

We both rely on David Anthony’s The Horse, The Wheel and Language, as the best source on I-Es. This book was published after I had completed first draft of my chapter on Indo-Europeans. There were many good sources but best before Anthony was JP Mallory’s In Search of Indo-Europeans. Their works reinforce each other. Indo-Europeanists are very careful not to identify IEs as white, and both Anthony and Mallory do no understand aristocratic nature of IE rule, they get confused with general Marxist use of this term and call elites elsewhere “aristocratic” even as they point to traits of IE rule that were not found elsewhere and were singularly aristocratic.

I intend to return to IE subject once I get past a fourth book I am writing now. Lots of new stuff coming out. Very important research to negate notion of “Judaeo-Christian” origins of West.

I like to think of the Judaeo-Christian “origins” as the means that protected the West from outside invasion. After all, it was Christianity that united us against muslim invasion (and I do feel like the lack of devotion nowadays is a major player in what’s happening in Europe right now). As for the Judeo part, it’s mostly a figure of speech really. What propelled the West forward was the other root: Antiquity. Or, in other words, the brilliance of the caucasian mind – which is more advanterous, emphatic and inovative than any other mind out there.

Thanks for this article, it arrived in timely fashion with me having just finished Collin Cleary’s excellent review of Duchesne’s book.

I am curious about the period between the end of the Roman Empire and the Reformation. Did the Franks revert back (it does strike me are a reversion) to something more closely resembling the original Aryan warrior aristocracy in Feudalism? Why did the Franks not see the Romans political system as something they could build upon? It would presumably not been completely foreign to them being of IE descent themselves, or perhaps not.

The Franks did not revert back to feudalism; rather medieval feudalism grew out of their already developed chiefdoms, with leaders granting followers fiefs in return for services, which had a decentralizing effect, but key of feudalism (from aristocratic view) is contractual nature of agreements by free men.

Roman institutions had been in decline for a long time; central controls hanging by a few ropes, and the Franks, and other Germanic tribes had been under Roman influence for a long time, no longer small war band but full chiefdoms before they broke through Roman defenses in the fifth century.

I didn’t mean the Franks reverted back to Feudalism but that Feudalism was a reversion to something less “sophisticated” than the cosmopolitanism of the Romans. I do take your point and it answers my question. Thank you.

The Franks most definitely *did* build upon the Roman system – after all, they (re-)established the Roman Empire (later, ‘Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation’) – as did the Ostrogoths and their successors, the Lombards, in Italy. Even the Vandals in North Africa became Romanised to a large degree.

The ‘Aryan aristocracy model is certainly present in the Lombard case, where society was governed by ‘arimanni’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arimannus) – the root, I believe, is precisely the one for ‘Aryan’, *ar – bound together by loyalty to a chieftain. Also prominent is the ‘Männerbund’ model, which is interestingly (and curiously) described at the beginning of the most important history of the Lombards, Paul The Deacon’s Historia Longobardorum:

“They pretend that they have in their camps Cynocephali, that is, men with dogs’ heads. They spread the rumor among the enemy that these men wage war obstinately, drink human blood and quaff their own gore if they cannot reach the foe.”

(cf. the Norse Ulfhednar…)

Very interesting, thanks.

Fascinating topic, but I’m slightly confused by the talk about Italian identity in Roman times. As far as I’m aware, there never was any such a thing (at least, in any meaningful sense). Maybe the author means ‘Italic’? (As in, pertaining to the Italic-speaking tribes of Latium?)

The various peoples of the peninsula adopted Roman identity (and citizenship) progressively, just as other peoples did across the Alps or Mediterranean. Some did so earlier (e.g. Veneti), others later (most Gaulish tribes, Rhaeti). Then under Augustus the province of Italy was established, as an administrative unit. But the same process of adoption of Roman identity applies to the Empire as a whole and is quite independent of ethnic identity, so much so that we speak of ‘Romano-British’ identity to describe the native (Celtic) elite of Britain who chose to adopt Roman mores.

So over the centuries the concept of ‘Romanness’ emerged, although the term itself (‘romanitas’) is attested rather late (Tertullian, I think, so 3rd cent.). In later centuries it eventually came to describe the Christian citizens of the Empire by contrast to the heathen barbarians, and it remained the term used by the Orthodox Greeks to describe themselves (‘roimioi’) – basically until the early 19th century, when the term ‘Hellene’ was revived). But I’m going off track.

So what I’m trying to say is: 1. that I doubt there ever was such a thing as an ‘Italian identity’ in Antiquity; and 2. that Roman identity became non-ethnic early on. I’m also pretty sure that the Romans had no ‘racial’ consciousness in our sense of the term, since they perceived non-assimilated Germanics and Nubians or Ethiopians as being equally barbarian. The same applies to the Greeks. If anyone has any evidence to the contrary, I’d be curious to see it.

I don’t disagree with your comment. My main disagreement is with image of Rome as a multiracial-multicultural empire; we really don’t know to what extent Italians had an ethnic identity except that they were granted citizenship pretty late in Rome’s history, and that Romanization, history shows, really worked in the European areas of empire, and that Medieval Europe, and West thereafter, always valued legacy of Rome, in a way that Egyptians, Mesopotamians, North Africans never have. The Romans identified with the Greeks, and the Germanic kingdoms that emerged out of former Roman lands, retained legacy of Rome, and America founders established their republic from their knowledge of Roman institutions.

Thank you for your response. I’m not suggesting that Rome was multiracial, although this is what left-leaning historians are now suggesting, basically with no evidence to back it up. The most egregious case probably being Mary Beard… I just think it is important to bear in mind that ‘Whiteness’ or ‘Europeanness’ emerged much, much later as concepts – at least as far as we can tell. Of course, polemical affirmations of Roman ethnic identity vs. the east can be found in Republican times (I’m thinking of good old Cato The Elder here).

I might also point out, obvious as it may be, that the extension of citizenship to the whole Empire in 212 was purely due to fiscal reasons. People who speak of the Antonine Edict as though it were part of some grand ideological scheme are way off.

I’m much looking forward to the third part of the review.

“My main disagreement is with image of Rome as a multiracial-multicultural empire; (…).

I think it has been established pretty well that race mixing and citizenship granting to non-Romans was

one of the main reasons of the fall of Rome.

The Race Change in Western Europe

http://www.askelm.com/people/peo011.htm

“(…) what Professor Frank discovered in Latin inscriptions which he found in and around Rome. What he uncovered was proof that a fundamental change of race occurred in the Italian peninsula between the 2nd century B.C.E. and the 3rd century C.E. The records of the monuments attest to this change. What we will discover is Chaldean, Anatolian, Syrian, Phoenician, Edomite, Samaritan (and some Egyptian) racial stocks replacing the earlier Latin races in Italy.”

Thanks for sending this link. It reinforces argument that Rome experienced considerable race mixing, though is a different argument from the way you use this link to state that race mixing was the cause of the decline of Rome. The claim that “the remnants of the Latin race were completely submerged by these incoming Semites” is a big exaggeration. None of the sources provide quantitative evidence supporting this claim, although I do take the passages cited seriously.

Tenney himself admits that the evidence is not solid: “This evidence is never decisive in its purport, and it is always, by the very nature of the material, partial in its scope…”

But he still insists that “Juvenal and Tacitus were not exaggerating. It is probable that when these men wrote a very small percentage of the free plebians on the streets of Rome could prove unmixed Italian descent. By far the larger part ― perhaps ninety percent ― had eastern blood in their veins.”

How does he know they had 90% if no one ever studied race mixing in Roman times? The author goes on to say “about ninety per cent of those people living in Italy in the 1st century had originally come from the eastern parts of the Roman Empire.”

I don’t believe this number. At the same time, at height of empire, the slave population constituted about 30% or even 35% of the population in Italy, which is a lot. If most of these slaves were from the East, then the argument for race mixing becomes strong. The cited words about decline of native Italians and how “foreigners, especially from Syria, Samaria, the Levant and Asia Minor took their place”, are quite compelling.

I just checked what I wrote about this and there is actually a typo that may give impression that I was too dismissive about presence of foreigners in Italy. It reads now: “According to David Noy, free overseas immigrants in Rome — never mind the Italian peninsula at large — might have made up 5% of the population at the height of the empire, which is to deny Orientalist elements among the enslaved population.”

I think it should be evident from the logic of the sentence that I meant to say “which is *not* to deny Orientalist elements among the enslaved population”.

Still, if the passages in the article about Tenney are correct, then I did underestimate greatly, typo or not, the presence of Orientalist elements among the enslaved population. I will have to examine this topic again to be sure next time.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment