A Pocket Full of Posies

Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, the Comic

Part 2

Michael Walker

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

What, then, of Craig Russell’s graphic art? Enthusiasts of either opera or graphic art will probably find great pleasure in Russell’s Ring. The book — some muddled scenes such as the discovery of the sword excepted — is easier to follow than Wagner’s 16-hour cycle of music-dramas. Admirers of Craig Russell have a 448-page feast before them, while opera lovers are likely to be intrigued to discover how a comic artist presents one of the most famous of all operatic works.

It must help this book’s popularity that Craig Russell has hardly any competition to contend with. Gil Kane and Roy Thomas published a monthly comic serialization of the Ring Cycle beginning in 1989, and this, too, was published in book form. Kane’s is the only other graphic novel version known to this reviewer. By contrast, Wagner’s operas have inspired a plenitude of painters and graphic artists. A very handsome, lavishly-illustrated edition with an English-French-German introduction was published in 1995, with the title Das Werk Wagners im Spiegel der Kunst (Wagner’s Work in the Mirror of Art), by the Grabert publishing house. The book is lavishly illustrated with plates showing postcards, postage stamps, posters, sculptures, and paintings based on scenes from Wagner’s operas. It was published before either the Kane or Russell books, however, although they probably would have received at least a mention.

Any assessment of Craig Russell’s interpretation must necessarily be subjective. Does one have preconceptions of what Wagner’s protagonists should look like? How does one relate graphic depiction to the music? Some will approach this book with no knowledge of the Ring Cycle and therefore no preconceptions about how the characters should look, while others will have very definite ideas on the subject indeed. The moment he draws a figure, Russell is therefore sure to displease some folk, just as different embodiments on film, stage, or in the graphic art depicting famous literary characters — say, a Miss Marple or a Romeo — will evoke different subjective reactions.

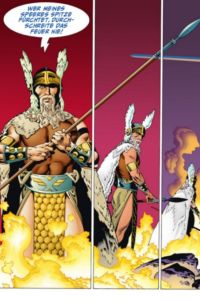

Russell is faithful to Wagner’s notion of Odin/Wotan as “primal being” — the first Adam, the first human, not omniscient and not essentially different from mortal human beings, but yet a God. Russell’s portrayal of the Ring Cycle also presents the universe more like a great thought than a great machine, and that presentation is likewise in accord with Wagner’s mysticism. Russell’s cartoons are focused on the natural and mythical world, not the mechanical or artificial, and it is easy to understand why he was attracted to Wagner’s world.

Several of Russell’s character portrayals diverge markedly from traditional embodiment of the archetypes of legend. Dwarves in legends and fairytales, for example, are usually traditionally drawn with long noses and a mass of wild hair. Arthur Rackham’s spindly, diminutive, long-haired, beaked Alberich is true to type, and Gil Kane’s Alberich is similar, except that he (himself Jewish; his name at birth was Eli Katz) draws Alberich as closer to an anti-Semitic caricature than Rackham does. But Russell’s Alberich is quite different to Kane’s and Rackham’s. He draws Alberich with neither beard nor hooked nose, and far from being hirsute, he is nearly bald; only occasional wisps of unhealthy, long-looking hairs sprout here and there from his head and over the rest of his body. Russell’s Alberich appears disheveled, dirty, and dubious, but reasonably strong and agile — certainly not obviously a dwarf, fairytale or otherwise. With his unhealthy rubbery appearance, Russell’s Alberich is reminiscent (intentionally?), if of anyone in fantasy tales, of Tolkien’s Gollum.

Alberich’s brother Mime looks neither like a traditional fairytale dwarf nor like Russell’s Alberich. He is also drawn to look disreputable and untrustworthy. But Russell’s Mime is a short and stocky man, suggestive of someone unfit and unhealthy, who one would expect to easily run out of breath. He has greasy-looking, unkempt, jet-black hair, and most of his teeth are missing — a feature which Russell’s drawings show very clearly. If Russell is trying to avoid anti-Semitic caricatures, he has certainly not departed from the caricature of villainous intent reflected in physical defects and ill-health. His Mime and Alberich are indisputably of “bad blood,” whatever else they are.

You can buy Alain de Benoist’s Ernst Jünger between the Gods and the Titans here.

Craig Russell also departs from tradition in his depiction of the giants. Fasolt and Fafner are stout, but not tall or imposing. On the contrary, they appear as shabbily-dressed, dim-witted but pragmatic, slow but stubborn types, pallid and everyday, with typically German representatives of their kind: fleshy, overweight, pale-skinned. Fafner sports a thick, brown, very modern and German-looking mustache. Craig Russell’s Fasolt and Fafner are thus nothing extraordinary. They are the kind of folk one might encounter in a shopping mall and not look at twice. By the standards of graphic art, they are crudely drawn. If they evoke curiosity, it is in the negative sense of shocking the reader that they look so ordinary and mundane.

Russell does not extend his originality to the depiction of the Gods Donner and Froh. They are simply — and in the smaller panels, very simply — depicted in the way they have been drawn by thousands of Marvel artists thousands of times. I suspect that anyone without Craig Russell’s reputation would have been taken to task for the crudity of several drawings in this book, and especially — but not only — his drawings of the minor Gods. The truth is that in several panels in this work, Russell draws his figures in a slapdash and uninspired way. Apart from one dramatic panel where Donner is superbly drawn, hammering the bridge to take the Gods over to Valhalla, the Gods other than Wotan and Loge are not drawn in a memorable way at all. Any competent graphic artist could have done as well.

Russell’s Siegfried is driven by his will, as reflected in the artist’s relentless depiction of his searing, intense, and intensely blue eyes (when Siegfried realizes that Wotan is his father’s murderer, Russell devotes an entire panel to Siegfried’s two eyes alone). Both Siegfried and Brünnhilde are very much mortals, handsome but not extraordinary in appearance, and in fact they were drawn from live models and are not primarily products of the artist’s imagination. Russell is known for his preference for drawing from photographs or human models directly, rather than developing figures from rough sketches. In fact, casting was needed for models for some of the characters in Russell’s Ring. This often makes his large panels showing a single figure extremely effective, for example the panels showing Siegfried forging broken pieces of his father’s sword, or Brünnhilde’s greeting to the Sun after Siegfried has woken her, or Wotan’s dark silhouette when he stands before his daughters, calling out for Brünnhilde. Such panels — and there many of this kind — are superb.

Some physical features acquire symbolic status — Siegfried’s piercing blue eyes and Brünnhilde ‘s abundant blonde hair come to mind — but Russell’s characters are for the most part realistically depicted, although in one or two of the panels they resemble statues more than living beings: for example, Siegfried when he has forged Nothung, Wotan on his horse, or Brünnhilde riding Grane into the fire at the end of Götterdämmerung. Wotan is very imposing throughout: godlike, yet at the same time very human. He is arguably the most successfully-crafted character in this book. Russell’s leading characters are strongly-portrayed individuals whose individuality is unmistakable. Sieglinde, for example, is very credible and very realistic, albeit simply drawn; with a few artful strokes, Russell succeeds in depicting her contempt for Hunding and her despair following Siegmund’s death.

But what was Craig Russell thinking when he drew the dragon guarding the Nibelung’s treasure? His drooling dragon is only somewhat larger than Siegfried, thereby giving the unfortunate impression that Siegfried is more bully than hero. Siegfried’s slaying of the dragon as depicted by Russell appears neither fearful nor even heroic; more like the gratuitous slaying of what looks to be an amiable large, green lizard. Russell’s dragon is reminiscent of a Comodo dragon, but bright green and more dainty and less repellent. The dragon is unlikely to evoke fear in many people, and certainly not in Siegfried. Even in this book, Craig Russell draws a more fearsome dragon, namely when Alberich demonstrates to Loge the power of the magic helmet, the Tarnhelm, by turning himself into a dragon. We only have to consider how many artists have depicted dragons far more frightening and memorable to wonder why Russell literally made light of his dragon. Take, for example, Hermann Hendrich’s gloomy and awe-inspiring painting of Siegfried and the dragon; or in the world of comic art, the nightmare dragons of a Michael Whelan. Perhaps the dragon’s smallness is an intentional depiction of the dragon as seen through Siegfried’s eyes, because he mocks it and feels no fear. That would explain it, but it adds to the overall impression that the artist is at pains to avoid giving offense or invoking fear, awe, or disgust.

While the drawing from models requires technical skill rather than imagination, it would be entirely wrong to think that Russell demonstrates no imaginative skill in this work, for when it comes to converting the power of a Wagnerian Leitmotiv to imagery, Russell’s imaginative powers are immense. He is prepared to devote entire pages to wordless exchanges and events, in keeping with the role of music in Wagner’s Ring and with the fact that there are long sequences in all four operas, and not only in the overtures, in which the orchestra plays while nobody sings.

Momentous orchestral moments in the Ring Cycle are depicted by Craig Russell with dramatic images in large panels that correspond to the dramatic atmosphere created by the Wagnerian Leitmotiv, whose emotional impact and resonance Russell’s graphic art seeks to emulate. For example, after Siegmund has drawn Nothung out of the ash tree and holds it up, in that glorious moment of triumph in Die Walküre when the sword Leitmotiv sounds, Russell draws huge concentric circles encircling what must be a center of pure light that is just out of view in the top left of the panel. The colors are brown, yellow, and blue.

When Siegfried encounters the Wanderer on the mountain encircled with fire, the two confront each other over three pages of Russell’s panels without dialogue. Two panels in gray and white represent Siegfried’s memory of Fafner’s death, then Siegfried’s blue eyes, and then he looks into the Wanderer’s blind eye. In that eye, first colored entirely black, he sees a solitary yellow flame, and then, within the flame, the face — the face of his bride-to-be, Brünnhilde. A white spark explodes on the sword, then there is a full-length panel showing a white flash of lightning, then a large panel in which we see Siegfried shattering the Wanderer’s staff — the staff which we saw Wotan fashion from Yggdrasil earlier in the tale — also depicted in a series of panels drawn without words.

The artistry’s dramatic realism is reinforced by the artist’s repeated use of close-up portraits and Russell’s skill at providing the graphics to embody the symbolism of the Wagnerian Leitmotiv. The overture to Das Rheingold is depicted first as a hand with a ring on its finger stretching up toward the rising (or setting) Sun, then Nothung the sword, then little drops of water falling into restless waters, and then the ash tree and the three Norns of fate. Then, in only brown and yellow tones and without words, there is a depiction of Wotan’s sacrifice of an eye to achieve wisdom and his crafting of a spear out of Yggdrasil, the world ash tree.

These sensitive graphics are in sharp contrast to the opening of Rheingold itself following the overture, showing the three Rhine Maidens singing in the Rhine. This is depicted in a way reminiscent of a Marvel comic, with simple, bright colors and energetic gestures. The coloring in Das Rheingold’s opening panels is very bright and simple, with the exception of Alberich’s. He emerges from a pitch-black hole and is depicted, in stark contrast to the brightly colored Rhine maidens and the clear blue Rhine waters, in subdued grays and mauve. Russell’s Rhine Maidens are for some reason not entirely naked; their modesty is maintained by a flimsy green material which looks like water arum and serves the same function as the fig leaves which Popes ordered to be placed on pagan statues. By contrast, Rackham and Kane’s Rhine Maidens are unblushingly naked. Kane’s are in fact erotic and knowing, while Rackham’s are seemingly oblivious to their nudity, naked without shame or even knowledge, like Adam and Eve in Genesis.

Russell’s decision to depict the Rhine Maidens with due modesty may have been made with a view to making his work more family-friendly, but reinforces the impression that a domestic and exciting, yet inoffensive fairytale is being told, not a Norse legend. Of all the creatures in the Ring Cycle, the water nymphs can hardly be expected to wear clothes, for they are the very embodiment of nature as it was before human greed. The possession of clothes can only take place in a later stage of human evolution. On stage, flowing white garments can be used to suggest water while avoiding nudity — but Russell’s water arum can only be seen as an intentional clothing. It is not just the Rhine Maidens who are portrayed with self-conscious modesty, either: Russell is painstakingly restrained in all matters in the Ring related to sexuality. This comic book is thus a very “polite” and very “classical” presentation of the Ring Cycle.

Siegmund’s words and Wagner’s subsequent brief stage directions at the end of the Die Walküre’s first act may cause disquiet, embarrassment, or amusement:

Siegmund:

Braut und Schwester

bist du den Bruder-

so blühe denn Wälsungen Blut!

Er zieht sie mit wüthende Gluth an sich: sie sinkt mit einem Schrei an seine Brust — Der Vorhang fällt schnell.

Siegmund:

Bride and sister art thou

to thy brother

so let flourish the blood of the Wälse!

He draws her to him with a raging, passionate fury: She utters a cry and falls across his breast — the curtain falls rapidly.

In Russell’s depiction, there is no “raging, passionate fury.” The two are restrained and polite. Our last view of them in the first act is as two white silhouettes in a heart-shaped black space, running hand-in-hand under a huge moon.

You can buy Collin Cleary’sWhat is a Rune? here

But this scene is not the end of the first act of Die Walküre in Russell’s adaptation, as one might expect. An entire subsequent page is devoted to panels showing the drugged Hunding in an unquiet sleep on his bed, calling out to Fricka and then snoring in such a way that leaves his lips in a series of 11 diminishing speech bubbles passing through an inappropriately perfectly rectangular window, with the word Inzessst in each bubble!

Many such small amendments or imaginative additions to the opera seem to serve the purpose of making Wagner more palatable to a modern readership: make sure the incest is roundly condemned, avoid nudity, avoid anti-Semitic stereotypes. If there were a term “emotionally correct” corresponding to “politically correct” describing behavior which avoids emotionally embarrassing, controversial, or provocative terms, it would apply to Craig Russell’s depiction of the Ring Cycle — with the exception, however, of the Nordic type. Russell’s determination to be faithful to Wagner’s story does not permit him to betray Wagner’s faith in the power of blood so far as Wotan’s progeny is concerned. Siegmund, Siegfried, and Brünnhilde are all portrayed as ideals of Nordic beauty.

Russell is excellent at telling stories in pictures, and it is in scenes where the characters do not speak that his art excels, using superb single images of individual characters, their gestures, and their decisive movements. His use of shadow to indicate mood is exemplary; for example, there is a superb, beautiful drawing filling an entire page of Loge about to lead the Gods into the Nibelung cave which is both menacing and magnificent. The close-up view of Alberich’s face and shoulders, half a page in size, as he warns Wotan of the ring’s curse with a mixture of fear and loathing; Fasolt swinging his club in order to commit the Cain murder; and Brünnhilde in her madness before her sacrifice as well as the sacrifice of the world are all memorable and very skillfully drawn. It is with such imaginative, large-scale panels that Russell shows himself to be a master of his craft, and it is these remarkable panels which constitute the truly extraordinary and unforgettable aspect of his work.

Russell is an adroit chooser of panel size, and he takes great pains to ensure that it suits the scene he is depicting. He uses very small panels to suggest quieter actions; for example, Sieglinde preparing the drugged drink for Hagen is shown in three panels that are just over an inch in height (the second panel showing her determined expression and contempt for her husband is a tiny 0.7” x 1.2” in size). When Mime recounts to Siegfried how he cared for Sieglinde and how she died in childbirth, panels in a monochrome light brown give the lie to his words: When he says “I did what I could for her” and “I was a great help to her,” we see Sieglinde in three small panels crying in pain, then a hand reaching out to Mime while he cowers in a corner. Finally, with Mime’s words “but she was too weak,” we horribly see only Sieglinde’s hand hanging to the floor in a small panel that is under half an inch, the sequence depicting her death in childbirth and showing what in the opera is only a suspicion – namely, that Mime did not help Sieglinde, and that she gave birth to Siegfried alone and without any assistance.

Color, or at least technicolor, is abandoned at appropriate moments, notably in flashbacks, for example when Sieglinde and Siegmund recount their stories; or when Hagen, Siegmund, and Sieglinde begin to realize that the pair are brother and sister; or when Siegfried tells Mime that the latter cannot be his father because he has seen in the forest that animal young resemble their parents and that animals are born of a mother and a father, and thus Mime’s claim to be his father and mother in one is biologically impossible since the beautiful Siegfried could not be the son of the hideous, cowardly dwarf. It would be against nature. “No toad engenders a frog, nor did you engender me.” This is of course the substance of Wagner’s intense belief in the reality of race and blood, and to deny it would be entirely to distort the opera, nor does Russell do so. His Siegfried indeed looks like Siegmund’s son.

The colorist for this work was one Lovern Kindzierski, although the colors were doubtless decided upon through teamwork. The use of color in this book is astonishing and memorable; after the dramatic large-scale figures, it is the most memorable aspect of it. At times, however, the coloring is extremely brash, so much so as to seem unnatural. For example, the bridge into Walhalla looks like the coloring for a child’s coloring box or advertising logo. Although the overall impression of the coloring is of an imaginative and expressive feast, there are panels where the coloring is unnatural and crude, to the point that it leaves the reader wondering if it is intentional or rather evidence of carelessness or even a lack of time on the part of the colorist. The book certainly offers a riot of color, from the chalk blue of the Rhine to the greens of the dragon, to the red of Loge’s fire to the gray-brown of a world destroyed at the end of Götterdämmerung, to the rainbow colors and the pale green of hope — the little ash tree seeding again with its promise of life returning to the planet. The colors reflect the emotions of the characters and the mood of the music as well. The colors are chosen to accord with the symbol: red is not only the color of fire, but of power. The Nibelungen caves glow crimson, for example.

Russell and Kindizierski’s extraordinary and varied coloring represents sounds as well as emotions and situations. Mediocrity is brown and light violet, power is red, innocence is blue, and of course green is nature — although the combination of colors in this book goes beyond the simplicity of such symbolism. They mostly relate strongly to a particular Leitmotiv in Wagner’s music, although I could not understand why the clouds in Das Rheingold are colored a sickly pink.

Craig Russell is profoundly aware of the symbol of the ring and the meaning of cyclical history. His Götterdämmerung ends optimistically, albeit enigmatically (at least to this reviewer). After the Rhine Maidens have reclaimed the ring and Hagen has been drowned, the last panel of the page is jet black, with little more than a scratch of paler coloring and lines on the left side of the frame. There then follow seven pages in which Craig Russell indulges in his optimistic fantasy. The black of the Rhine becomes the black of the wings of the two ravens, Huginn and Muginn, and then we see Loge in Walhalla, who is killed by Wotan using his broken spear. It is at this point that Walhalla is consumed by fire. Then there are images of Nothung, of Siegfried, of Brünnhilde, of Siegfried and Brünnhilde together, and of the world after the apocalypse. A tiny water drop hangs from a broken stump, falling to earth — and from the ground, a sapling sprouts. All will be recreated, all will be reborn. Life will not be exterminated for eternity. Darkness cannot prevail forever. All returns and begins again, all is a wheel or ring of recurrence. The last image is of a new ash tree in a new world.

Despite many shortcomings, this is a remarkable book.

A%20Pocket%20Full%20of%20Posies%0AWagnerand%238217%3Bs%20Ring%20of%20the%20Nibelung%2C%20the%20Comic%0APart%202%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Related

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

Are Whites Finally Waking Up?

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Birch Watchers

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

-

Elizabeth Dilling on the Evil of the Talmud