2,012 words

He [Rousseau] had nothing new, but he set everything on fire. — Madame de Staël

Starting from unlimited freedom I arrive at unlimited despotism. — Shigalev, in Dostoevsky’s The Devils

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, not Karl Marx is the real father and inspiration for the theater of the absurd that is today’s Left. Rousseau’s “Man is born free, everywhere he is in chains” is the original formulation of the adolescent anarchist rally-cry, “Rage against the machine!”

Marx made the mistake of thinking that his economic and sociological generalizations harnessed to Hegelian metaphysics were science, and so he composed a set of predictions about the future of the modern world and an “action plan” that would make them come true:

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it. — Marx, Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach

His predictions, combined with his “workers of the world unite” action plan, became “the Revolution” and had great appeal to the action-oriented lads. But it turned out to be a Buridan’s Ass paradox: a hungry, thirsty donkey that is placed midpoint between a pail of water and a pile of hay dies because he can’t decide which way to go. In this case, the revolutionaries are the donkey. The water is the historically-determined outcome, and the hay is the volition of the proletariat that is paradoxically necessary to bring about what history has determined. Lenin ignored the paradox and went all in with the volition of the proletariat. History would be fulfilled if, Lenin astutely concluded, the workers were expertly guided by intellectuals such as himself, who made revolution their life-long profession — that is, the Communist Party leadership. The revolution of the workers would be initiated and organized by men who didn’t work.

You can buy Stephen Paul Foster’s new novel When Harry Met Sally here.

None of it mattered. Marx’s predictions never, so to speak, materialized. His action plan was implemented by psychopaths, and over time it was improvised until there was no plan: Lenin to Stalin to Khrushchev to Brezhnev to Gorbachev. From command-terror to the cult of personality to stagnation and corruption to internal collapse — the dream was a long-running nightmare, a human disaster of epic proportions, a study of government by gangsters. Marx was a pretend-scientist, and after a time, most everyone quit pretending that he was one.

Marx the man became an “ism,” Marxism, a prophetic religious movement with an infallible scripture, fanatical followers, enforced orthodoxy with splintering sects, and the promise of perpetual equality and plenty — and like the Second Coming, always somewhere in the future. Whenever and wherever the action plan plunged itself into mass murder and famine, as in Russia and China, the true believers refused to retreat. They were rescued by the “Great Tautology”: What had failed was not really “true Communism,” because true Communism had to be successful. Scientists, engineers, economists — few, if any, know or care about Karl Marx any longer. He remains popular with English professors, who find in his largely unreadable tomes a “theoretical” argot that gives a ponderous voice to the resentment they feel for having salaries lower than business professors. Only from a “Distinguished Professor of English Literature,” Terry Eagleton, would come a book entitled Why Marx was Right.

Rousseau was a very different creature from Marx, and his legacy and influence were more insidious and pervasive. Romantic, sexually deviant, and intermittently psychotic, the Swiss vagabond who shuffled off the five children he fathered to foundling homes was the personality prototype of your twenty-first century, blue-haired social justice activist. An intellectual celebrity with groupies, even the skeptical, conservative David Hume fell for his act for a time. No one would envision Marx or Stalin accoutered in pink, leading a troupe of Drag Queens at the head of a gay pride parade. Rousseau? Definitely.

Rousseau was a man of grievances. The oracular pronouncement that opens On Social Contract, “Man is born free but everywhere is in chains,” is emblematic of a view of the human condition that conceives of human beings as naturally good and benevolent, perpetually struggling in a society that represses that natural goodness and corrupts the spontaneous benevolence of the individual, making him miserable.

Civilization was a problem for a Rousseau, not a solution for natural human limitations. To be civilized for Rousseau meant to submit to the repressive and coercive forces of social organization that produced unjust and arbitrary inequalities:

The first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows, “Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.” — On the Origin of the Inequality of Mankind

Primitive man was free, equal, and happy; modern man is trapped in a rigged system that empties out his authentic self. Rousseau’s genius was his creation of the ideology of “victimhood.” Victimhood fueled the ideological engine of the French Jacobins who set about demolishing l’ancien régime as well as that of the Bolsheviks and their 70-year failed experiment with Homo sovieticus and the kingdom of freedom.

Self-righteous victimhood was the predominant motif that drifted out of the turbulent wake of Rousseau’s social philosophy. Marx wrapped a theoretical structure around Rousseau’s notion of victimhood, making it the proletariat’s motivational energy: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles” (The Communist Manifesto). History’s victims, the oppressed workers, would in the end overthrow their capitalist oppressors. The dynamic of oppression and domination for Marx centered on economics and the ownership of the means of production. Revolution was about making the ownership of the world’s bounty fair.

The cult-Marxists of the Frankfurt School turned away from economics and ownership and toward Rousseau and “liberation” — not of the worker, but of “the person.” The unionized, blue-collar workforce of the mid-twentieth century was not the enlightened, unchained proletariat that Marx predicted would rise up, take rightful ownership, and build the socialist workers’ paradise. A suburban homeowner with a good union wage, the United Auto Workers assembly line worker also had paid vacation, health care benefits, and maybe even a motor boat beside his two-car garage. He was looking very bourgeois, albeit more philistine: the white, bitter clinger to his “guns or religion or antipathy toward people who aren’t like [him],” as Obama described members of the proletariat; reactionary bigots who had botched their historically-assigned role.

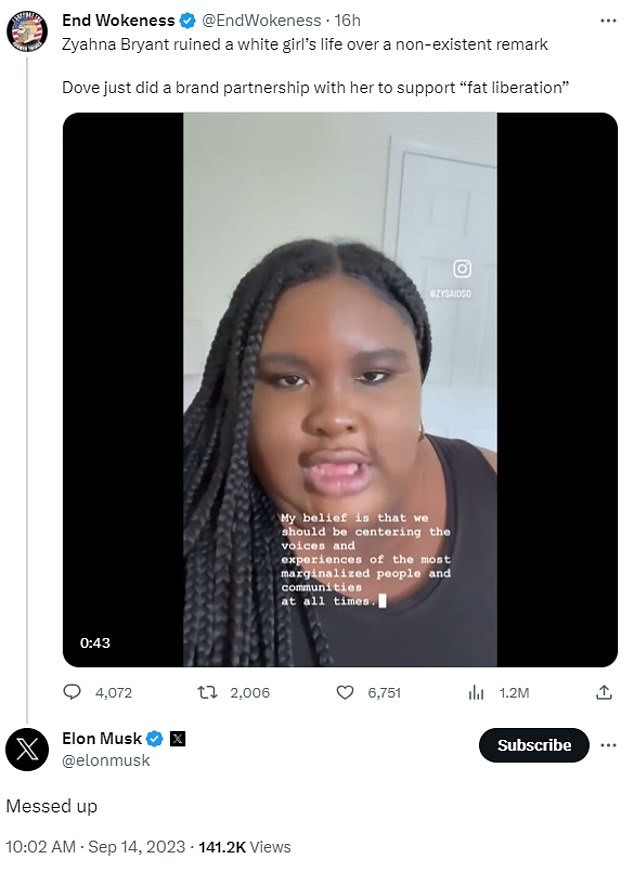

“Liberation,” however, continued as the cry of the Left, but not for working-class white people. Being “liberated” meant shedding those inhibitions — “hang-ups,” in the argot of the 1960s counter-culture — that put a brake on those sundry forms of self-expression that had come into fashion. Liberated self-expression — waving the middle finger at the oppressor du jour — then went full throttle. In 2023 it amounts to systematically coercing the approval of misfits, degenerates, and self-dramatizing weirdos. “Liberation” looks like Zyahna Bryant, who was chosen by Dove Beauty as their “fat acceptance ambassador,” the vanguard of “fat liberation.”

For the cult-Marxists, victims were still in abundance, but they were looking very different than the lunch-bucket gang from the Marxist days of yore.

A more durable tandem of oppressor-oppressed than Marx’s capitalist-worker was needed, along with an update to the original action plan. Rousseau’s “noble savage” was perfect to play the role of the oppressed. But who would be the noble savage? Well, fortunately, the black man was available. For the “savage” part, there was no competition. Making him noble was at the very least challenging and required creative imagination and fanatical persistence in the face of obdurate reality. Think, however, of how well it came together with George Floyd. First, there were the shackles of slavery. Then followed the morally crippling burden of “racism,” an abstraction more serviceable than the physical chains far in the past. “Racism” was a brilliant, ennobling move because it lent itself to endless adjectival enhancement — “economic racism,” “covert racism,” “systemic racism,” etc. — and it ensured the permanence of righteous victimhood and the unalterable, permanent malignancy of the oppressor class. Recall President Obama near the end of his second term tut-tutting his interviewer: “Racism, we’re not cured of it.”

“Equality” is the elixir of the anti-racist, and “equality” was hard-wired into the thinking handed down from Rousseau. It moved into the centerpiece of the religion of contemporary civil rights, a sacred dogma that refuses to be falsified by experience. That the decades of massive efforts to bring it into reality have dramatically failed are just further confirmation of the malevolence of those who benefit from inequality in the form of “white privilege,” sustained by ubiquitous “racism.”

Rousseau’s insistence on the reality of an innate, natural human goodness and the inherent repressiveness of outmoded institutions, with their entrenchment of inequalities, was an exquisite creation of what turns out to be a proto-modern mind. He was a thinker far ahead of his time. His ideas were destined to be an energizing ideological force with unlimited potential for the production of racial resentment — raw, festering, and intense as the inequalities persist — and for the dismantling of traditional institutions as revenge.

Jesse Jackson, who had an uncanny talent for maximizing publicity for manufactured grievances, led a band of protestors in 1987 who stood at the gates of Stanford University chanting, “Hey, hey, ho, ho, Western civ has got to go.” Here was an animus of implacable resentment and envy that the leading civil rights racketeers knew had a future with a huge payoff. It metastasized over the decades into a widely-orchestrated demand by the ruling class for the extinction of “whiteness.” The various tropes of victimhood with racism at their core are now firmly entrenched in our political discourse and mass culture along with a language developed and refined by the Illuminati from our best universities.

For Rousseau’s disciples, the gross disparities, innumerable inequalities, and the invidious comparisons that one inevitably finds separating human beings are the work of inherently corrupt social forces. The late eighteenth century saw the terrible birth of total revolution, a new, totally modern phenomenon. In the twenty-first century, these imputed corrupt social forces have been reductively transmitted into “systemic racism,” with “diversity, inclusion, equity” as the religious incantation supplanting the revolutionary “liberty, fraternity, equality” cry of the Jacobins.

One of Rousseau’s great ironies is that his reaction against the crushing of the authentic self by a false and hypocritical society unleashed a subjective and emotive orientation steeped in self-righteous resentment that has only increased the alienation associated with modern life.

Rousseau’s passionate theorizing has become a familiar underpinning of the contemporary social justice attacks on traditional institutions and the normative constraints that sustain them: “Man’s wisdom is but servile prejudice, his customs but subjection and restraint.” (Emile) The constraints have come to be viewed and resented as the embodiment of something quite nefarious: engines of social exploitation and sources of racial inequality. Laws, rules, and norms in their abstract form appear to be necessary or fair or reasonable. But constraints, alas, are ultimately linked to constrainers — the wrong sorts of people hiding behind them with their rationalizations. They enjoy the benefits that accrue from the advantaged position they use to exploit those they have disadvantaged. Today they are white people who benefit from the failure of blacks to achieve their rightful place in Western society as . . . equals. They are the true enemies of “our democracy.” This is Rousseau’s legacy as embraced by his ideological progeny. Rousseau’s “victimhood” is alive and well in the twenty-first century.

Rousseau was the intellectual’s intellectual, the theorist, richly infused with the indignation that the contemplation of social misery arouses, and the revolutionary. As the philosopher of misery and the original theorist of socially-determined victimhood, he cast the original mold for the production of the “socially conscious” moralist, the “social justice warrior,” and the “anti-racist” hustler.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

The Folly of Quixotism, Part 1

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

-

Elizabeth Dilling on the Evil of the Talmud

-

Wholesome Escapism: The BBC Farm Series

4 comments

Outstanding essay. Joseph de Maistre was right to identify Rousseau as the font of modern evil.

I must say that Rousseau did have some interesting ideas. The problem arises in taking any of them too seriously.

It is an oversimplification to call Rousseau the “prototype of your twenty-first century, blue-haired social justice activist.” Alain de Benoist has a more nuanced take: https://counter-currents.com/2012/06/re-reading-rousseau/

Rousseau never kept his children long enough to see that they are little barbarians who need to be civilized into a society rather than the innocents who the collectivity corrupts.

Who was it that created society but those very people who are “born free but are everywhere in chains.”

Doesn’t this undermine his premise?

Couldn’t Rousseau also be seen as the baby-daddy of that woman with the made up first name of Ayn with the atypical vowel who railed against the collectivity as the woke crowd blames White society? And what about the flower children of the 60’s revolution? Rousseau’s great granddaddy may be none other than Him who said, “Ye must be as little children to enter the kingdom of heaven.”

This was a very thought provoking article.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.