3,149 words

But there are in our country semi-Trotskyites, quarter-Trotskyites, one-eighth Trotskyites, people who help us, not knowing of the terrorist organization but sympathizing with us. — Karl Radek at the Moscow show trials, 1937

Leon Trotsky was attacked by an assassin wielding an alpine ax while sitting at a table in his compound in Mexico City on August 20, 1940. On the table was a manuscript, a nearly-finished biography — Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and His Influence – of Trotsky’s one-time comrade in arms, and later Bolshevik nemesis. The pages absorbed spatters of Trotsky’s blood from the blows to his head. The assassin was Ramón Mercader, undercover alias Jacques Mornard, a handsome, Soviet-trained Spaniard.

In order to gain access to Trotsky’s well-guarded compound, he seduced an American social worker, the truly homely Sylvia Ageloff, who was employed in Trotsky’s entourage. Cuban-born María Caridad del Río Hernández recruited Mercader. She was his mentally unstable mother. She was also an agent of the Soviet People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) during the Spanish Civil War, working in tandem with her lover, the shadowy, globe-trotting Nahum Eitingon. Eitingon, a Lithuanian Jew and polyglot, joined Lenin’s Cheka, the NKVD’s predecessor, in 1920 at the youthful age of 21. When he wasn’t distracted by womanizing, he devoted himself to forgery and the kidnapping and assassination of those who got themselves on the wrong side of the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

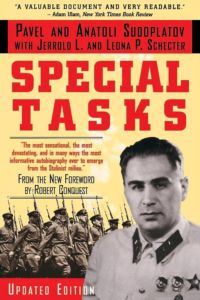

Pavel Sudoplatov wrote what has to be one of the more remarkable “tell all” books to come out of the Soviet Union: Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness — A Soviet Spymaster. In it, he devotes an entire chapter to the Trotsky assassination project, including how he was put in charge of it by Stalin himself. Trotsky, though powerless and on the run, loomed fervidly large in Stalin’s paranoid imagination.

Pavel Sudoplatov wrote what has to be one of the more remarkable “tell all” books to come out of the Soviet Union: Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness — A Soviet Spymaster. In it, he devotes an entire chapter to the Trotsky assassination project, including how he was put in charge of it by Stalin himself. Trotsky, though powerless and on the run, loomed fervidly large in Stalin’s paranoid imagination.

The book includes the following exchange:

Stalin: Trotsky should be eliminated within a year, before the war breaks out. Without the elimination of Trotsky, as the Spanish experience shows, when the imperialists attack the Soviet Union, we cannot rely on our allies in the Communist movement. They will face great difficulties in fulling their international duty to destabilize the rear of our enemies by sabotage operations and guerrilla warfare if they have to deal with treacherous infiltrations by Trotskyists in their ranks.

Sudoplatov: Stalin remained calm when I replied that I was not totally fit for the assignment in Mexico because I spoke no Spanish at all.

Stalin: It is your job and party duty to find and select suitable and reliable personnel to carry out the assignment. You will be provided with whatever assistance and support you need. Report direct directly to Comrade Beria and nobody else, but the full responsibility for carrying out the mission remains with you.[1]

“Full responsibility for carrying out the mission remains with you,” coming directly from Stalin, has to be the ne plus ultra experience of sphincter-clenching job assignments: A successful completion of the mission means that you might get to stay alive until your next assignment. Sudoplatov in fact lived to be 89.

When the operation was underway in Mexico City, María Caridad waited for her son in a car a few blocks from the compound to assist in his getaway after the hit. Trotsky, however, refused to go down as planned. He put up a struggle that allowed the compound guards to interrupt the murder temporarily and beat Mercader senseless. Trotsky died days later from his injuries.

The Mexicans eventually released Mercader from prison 20 years later. He made his way first to Havana, where he was feted by the Stalinist of the Caribbean, Fidel Castro. Then he was off to the Soviet Union, where he was awarded its highest civilian decoration, the Hero of the Soviet Union medal, by Alexander Shelepin, the then-head of the KGB, the NKVD’s successor. It is noteworthy that years after Stalin’s death in 1953 and the rehabilitation of many of his victims, the Soviet leadership continued to propagate Stalin’s fiction that Trotsky had betrayed Bolshevism. Stalin continued to reign over his surviving henchmen as a jealous and vengeful ghost.

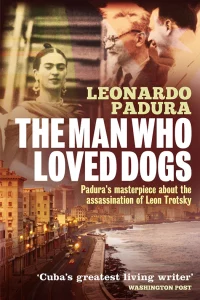

The planning, execution, and aftermath of Trotsky’s assassination is superbly and rivetingly recalled in all of its lurid, intriguing details by Leonardo Padura in a historical novel, El Hombre que Amaba a los Peros. It is available in an English translation as The Man who Loved Dogs. Padura, a Cuban, is also the author of a popular series of detective novels known collectively as Las cuatro estaciones, which was made into a Netflix drama, and featuring a veteran policeman, Mario Conde.[2] El Hombre is a masterful study that explores the pathologies that fester within the darker regions of Stalinist minds. In it, Padura masterfully interweaves three distinct narratives with flashback sequences that give the assassination a broader historical context and a profound philosophical-moral meaning: the exiled years of the complex tragic hero, Trotsky; the unfolding Stalinist treachery of Mercader’s handlers, including his fanatical mother, as the assassination plan unfolds; and the narrator’s disillusioning experience of the bleakness and misery of daily life in Fidel’s Cuba.

The planning, execution, and aftermath of Trotsky’s assassination is superbly and rivetingly recalled in all of its lurid, intriguing details by Leonardo Padura in a historical novel, El Hombre que Amaba a los Peros. It is available in an English translation as The Man who Loved Dogs. Padura, a Cuban, is also the author of a popular series of detective novels known collectively as Las cuatro estaciones, which was made into a Netflix drama, and featuring a veteran policeman, Mario Conde.[2] El Hombre is a masterful study that explores the pathologies that fester within the darker regions of Stalinist minds. In it, Padura masterfully interweaves three distinct narratives with flashback sequences that give the assassination a broader historical context and a profound philosophical-moral meaning: the exiled years of the complex tragic hero, Trotsky; the unfolding Stalinist treachery of Mercader’s handlers, including his fanatical mother, as the assassination plan unfolds; and the narrator’s disillusioning experience of the bleakness and misery of daily life in Fidel’s Cuba.

The Cuban narrator, Iván, is a lowly veterinarian assistant and aspiring writer. He has been living on the edge through the período especial en tiempos de paz that began in 1991, when the Cuban economy was devastated by the collapse of the Soviet Union. Upon the death of his wife in 2004, Iván begins to reflect on a personal experience he had had in 1977. On the beach he had met a mysterious old man walking two Russian wolf hounds. The dogs are what initially drew the two men together. The old man turned out to be Ramón Mercader, who is vacationing and dying from lung cancer. The encounter led to Mercader’s confession, which encompassed the bigger story of Trotsky’s fall from grace and the years of exile that led him to Mexico. We also hear Mercader’s tortured memories of the maternal malevolence behind his recruitment and the grueling training he underwent for the assignment by Soviet specialists in espionage and assassination.

Padura brilliantly captures the psychological anguish of this extraordinarily determined young man who is caught up in a vortex of world-historical forces beyond his understanding and control, and who is being manipulated by the worst kinds of human beings he had the misfortune to trust. Also interwoven into Iván’s storytelling are the grim details of his own fall from the Communist Party’s favor: life in a morally corrupt and physically decaying worker’s paradise, a late Soviet Union miniaturized, the bosses faking it and the workers hungry: “hungry Cubans in the ‘90s” is a salient motif. The book’s title is deliberately and referentially ambiguous: The three central characters — Leon, Ramón, and Iván — are all men who loved dogs.

By the time of his murder, the person of Leon Trotsky had been transmogrified, as we see in Stalin’s instruction to Sudoplatov, into “Trotskyism.” Many of Stalin’s high-ranking Bolshevik rivals — including Lenin’s favorite intellectual, Nikolai Bukharin — suddenly found themselves contaminated with this lethal heresy. Trotsky, however, had been widely regarded in the not-so-distant past as the number two Bolshevik behind Lenin himself, and the most likely of the Communist Party’s leaders to take his place. He was a writer and orator of considerable talent, and his formidable organizing and military skills as head of the Red Army greatly contributed to the success of the October Revolution, the Bolshevik defeat of the White Russians in the ensuing Civil War, and the regime’s ability to consolidate its power and entrench its rule. From an early age to his dying breath, Trotsky was a Communist to the core of his being. There was no limit to the number of eggs he’d happily have broken to make the omelet that he imagined would have made it all worthwhile.

You can buy Stephen Paul Foster’s new novel When Harry Met Sally here.

For those Leftists enamored with the idea of Trotsky as the prototype of the “good Communist” versus Stalin as the “bad Communist,” the famous anarchist Emma Goldman, in her Trotsky Protests Too Much, in reference to the Bolsheviks’ crushing of the Kronstadt sailor uprising in 1921, notes the clear-eyed difference between Trotsky and Stalin:

In point of truth I see no marked difference between the two protagonists of the benevolent system of the dictatorship except that Leon Trotsky is no longer in power to enforce its blessings, and Josef Stalin is. No, I hold no brief for the present ruler of Russia. I must, however, point out that Stalin did not come down as a gift from heaven to the hapless Russian people. He is merely continuing the Bolshevik traditions, even if in a more relentless manner.

Trotsky was less adept at political intrigue and wading through the slog of inter-Party feuds than his nemesis. He was also exceedingly vain and supremely arrogant.[3] His egotistical and contumacious personality made him many enemies within the Party. He completely underestimated his principal rival, Stalin, whom he disdained as a “colorless mediocrity.” The consummate organization man quickly outmaneuvered him. Almost before he realized it, he was first marginalized and then vilified, finally expelled from the Party and exiled from the Soviet Union altogether. Trotsky spent his last years running from country to country — Kazakhstan, Turkey, France, Norway — slightly ahead of Stalin’s killers, helplessly watching them murder members of his family, including his son, Sergei Sedov.

The opening of the door to his final destination, Mexico City, was made possible by his friend, the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

Rivera, like Trotsky, was a Communist on the outs with Stalin. Rivera lobbied Mexico’s Leftist President, Lázaro Cárdenas, who in turn granted Trotsky political asylum. Diego Rivera was a big man with a big personality who did big paintings. The Detroit Industry Murals are a set of frescos that were completed by Rivera in 1932. Its 27 panels depicting auto workers in the Ford River Rouge plant can be seen today in the Detroit Institute of Arts, where they surround the museum’s interior court.

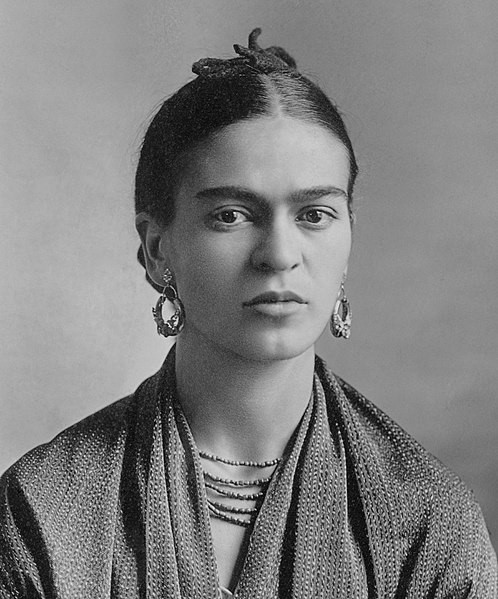

Rivera opened up his home, the Casa Azul, to the Russian exile and his wife, and Trotsky repaid his hospitality by seducing his crazy wife, who was a painter herself: Frida Kahlo.

The seduction may have been the other way around, but in any case, the cuckolded Rivera then parted ways with the peripatetic revolutionary. Trotsky secured the forgiveness of his wife and decamped with a small band of disciples to his new compound in Coyoácan, Mexico City. There, the Don Quixote of real Communism continued to do battle with the Georgian Prince of Darkness as the General of the Fourth International in quest of the “permanent revolution.” Reality from back home would soon crash Trotsky’s theoretician’s party in the form of a Spaniard aiming an ax at his head.

Trotsky’s years of experience with Stalin manifest a crucial aspect of the latter’s malevolent genius. Trotsky, the flesh-and-blood man, would be turned via Stalinist alchemy into “Trotskyism.” An “ism,” of course, is an abstraction, and “Trotskyism” was a particularly useful one for Stalin because it enabled him to remove any particular details of Trotsky’s life and career he wished, as well as any specific attributes of his personality or character that might have humanized him or detracted from Stalin’s official version of events. “Trotskyism,” like all of Stalin’s productions for public consumption, was a heavily-labored falsification.

Trotskyism reduced Trotsky-the-man to a vague, flexibly applied set of ugly qualities that could always be cast in treacherous opposition to the monumental achievements that Stalin single-handedly accomplished for the Soviet Union — all of those things that reflected his own personal greatness and genius. “Trotskyism” was merely shorthand, a label for a treasonous fifth column, and it was attached to almost anyone who had fallen into disfavor with the Kremlin Chief.

The 1937 Moscow show trials choreographed by Stalin featured Karl Radek, a loyal Bolshevik from the October Revolution days. Known for his biting witticisms and clever puns, he managed on the witness stand to have his coerced, Trotskyist-traitor “confession” take a wily jab at the Boss by facetiously decomposing those menacing “Trotskyites” into dwindling fractions of themselves. Just how does one become a “one-eighth Trotskyite,” and how threatening could he be? He got ten years in a penal labor camp — where he was killed.

Josip Broz Tito was Stalin’s faithful servant in Yugoslavia during the Second World War. Like Trotsky, he asserted and proved himself as an able Communist revolutionary who was successful in gaining power through his own efforts and talents. He declined to make the full bow at Stalin’s altar, and his success made him, like Trotsky, a hated rival rather than an obedient underling. Like Trotsky also, Tito the man morphed into “Titoism,” a word connoting dissonance and deviance that tainted the monolithic perfection of Stalin’s workers’ kingdom. Unlike Trotsky, Tito had an established power base in the Balkans which prevented Stalin from turning the principal bearer of this nefarious -ism into a corpse.

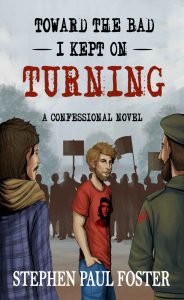

You can buy Stephen Paul Foster’s novel Toward the Bad I Kept on Turning here.

Stalin’s “-isms” — nebulous, protean abstractions that framed the opposition as human refuse — emerged insidiously, and seemingly out of nowhere. Loaded up with connotation and lacking denotation, they could be easily conjured and appear at any time, acting as amorphous placeholders for the current set of adversaries which in turn allowed him to change direction and shift alignments at will.

“Fascism,” from its original Stalinist deployment in the 1930s, was so durable as a word of abuse for the Left’s enemy du jour that it achieved permanence as a metapolitical weapon. The German Social Democrats were “social fascists” — at least until Stalin needed them in his Popular Front alliance to combat real “fascism” in the person of Hitler, but before he partnered with Hitler to grab a chunk of Poland. That lasted until the “fascism versus democracy” slaughter-fest which put him temporarily in cahoots with Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. Flexibility and durability kept “fascism” alive. 70 years after Nazi Germany’s destruction and Hitler’s demise, 63 million “fascist” American voters, according to pundits and cable TV talking heads, put Hitler redux into the White House.

Stalin is long dead, but Stalinist metapolitics is what drives the carnival-show politicking in twenty-first century America. Hillary Rodham Clinton carried on as Stalin in drag, with an expanded nomenclature of enemies of the people: “racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic” — a “basket of deplorables . . . thankfully not part of America.” Not thankfully, however, every one of these “isms” and “obias” is a metapolitical “gotcha” trap. No matter how you try to escape — “I’m sorry to be one,” “Please forgive me for being one,” “I’m not one,” “I think you’re one” — too bad, amigo! You remain one. It’s in your DNA, and that makes you “irredeemable.”

Our practitioners of metapolitics, like the Bolsheviks, connive at terrifying the faithful with incessant reminders that they are surrounded by the unfaithful. In the USSR, the unfaithful were designated so by virtue of their class origin, which made them enemies of socialism. In post-George Floyd America, it’s one’s race which makes one opposed to equality and a threat to “our democracy.” Class enemies (“kulaks”) then, and “white supremacists” or “racists” now. The existence of “racists” among the faithful keeps that “arc of the moral universe from bending toward justice,” which means they must be marked by the ruling class for elimination.

Stalin, when speaking on the subject of class enemies, never minced words. He put it this way in a speech in 1929:

An offensive against the kulaks is a serious matter. It should not be confused with declamations against the kulaks. Nor should it be confused with a policy of pinpricks against the kulaks, which the . . . opposition did its utmost to impose upon the Party. To launch an offensive against the kulaks means that we must smash the kulaks, eliminate them as a class. Unless we set ourselves these aims, an offensive would be mere declamation, pinpricks, phrase-mongering, anything but a real Bolshevik offensive.

An article from Harvard Magazine from 2002 has a similarly threatening ring:

The goal of abolishing the white race is on its face so desirable that some may find it hard to believe that it could incur any opposition other than from committed white supremacists. . . . Every group within white America has at one time or another advanced its particular and narrowly defined interests at the expense of black people as a race [who never advance their narrowly defined interest at the expense of anyone]. That applies to labor unionists, ethnic groups, college students, schoolteachers, taxpayers, and white women. Race Traitor will not abandon its focus on whiteness, no matter how vehement the pleas and how virtuously oppressed those doing the pleading. The editors meant it when they replied to a reader, “Make no mistake about it [no policy pinpricks or phrase mongering]: we intend to keep bashing the dead white males, and the live ones, and the females too, until the social construct known as ‘the white race’ is destroyed — not ‘deconstructed’ but destroyed.”

“Social construct” is sufficiently illusive to serve as a ruse, but “the goal of abolishing the white race” is openly, unambiguously genocidal in its meaning and criminal in intent — twenty-first Stalinism straight out of Harvard. That was written 21 years ago, and “conservative” white voices are still parroting that it is “not the color of their skin but the content of their character” that matters in America today.

The real Communism of Trotsky’s fertile imagination died in Mexico City. He was all pen and no sword; just Stalin without the muscle. The muscular Stalin delivered real Communism real hard, and it operated with practical maxims such as: “Show me the man and I’ll show you the crime” and “The people who cast the votes don’t decide an election, the people who count the votes do.” These succinctly capture Stalinism’s criminal ethos. It got its start in the Soviet Union and has matured in America, where the current gangsters in power have declared war on their own people.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] Pavel Sudoplatov & Anotoli Sudoplatov, Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness — A Soviet Spymaster, with Jerold and Leona Schecter; Foreword by Robert Conquest (New York: Little Brown, 1994), pp. 67-68.

[2] I was in Havana on a Potemkin tour with American Lefties in 2015. I did, however, manage to have a one-on-one conversation with the head of the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba and asked him about Padura. El Hombre had been published in Spain in 2009 and in Mexico in 2010 — but not in Cuba, of course, nor was it easily purchased in Cuba. The man told me that he was a good friend of Padura. When I expressed my surprise that a writer so critical of the regime’s shortcomings could live and publish unpunished, he smiled and said, “They don’t dare to touch him.”

[3] Robert Service, Trotsky: A Biography (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 4.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 1: Nowa Prawica przeciw Starej Prawicy

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Wprowadzenie

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 2

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc