3,129 words

Introduction

It can be instructive to look at the racial politics of 50 or 60 years ago, so here are three illustrative episodes. The first section below paraphrases six pages of Tom Wolfe’s essay “Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers” (1970). The second summarizes Wikipedia’s article about the Black Power movement (1965-c. 1985). The third gives an account of Afrocentrism (1970 to date). Each shows us a precursor of Black Lives Matter.

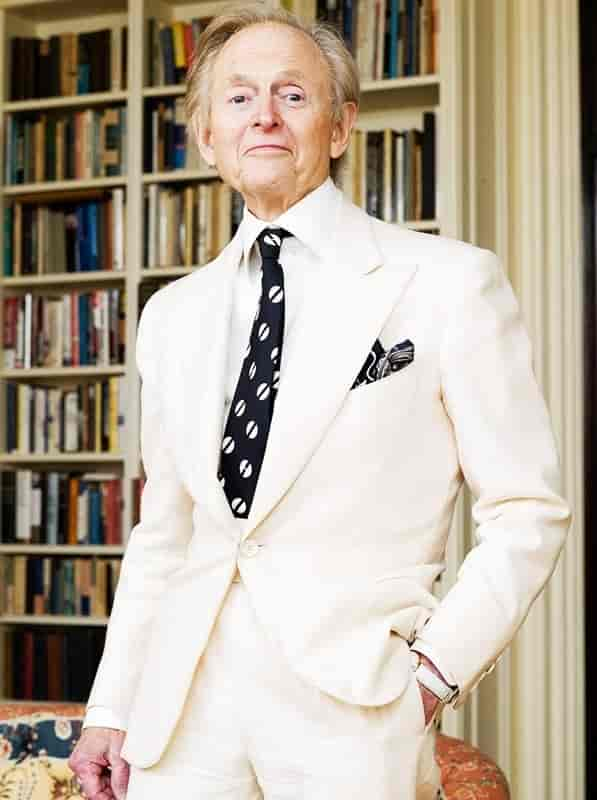

“Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers”

By “mau-mauing” Tom Wolfe meant the tactic used by non-whites to intimidate white officials such as those working at the Office of Economic Opportunity, who had benefits to dispense courtesy of the poverty program. The expression came from the short name of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, which fought the British and the Kenya Regiment in the 1950s in an attempt to regain land they saw as having been taken from them. During the uprising, which lasted eight years, the Mau Mau killed 32 whites and upwards of 2,000 of their fellow Kikuyu using machetes, clubs, and spears. As for the flak catchers, they were the officials who had to take whatever threats and displays of violence were directed at them by non-whites who wanted to get something out of them. Tom Wolfe’s 40-page essay is written in the style of the “New Journalism,” which incorporates much dialogue and many points of view.[1]

In the passage paraphrased below, a mau-mauing episode has just ended, with a group of blacks leaving a branch of the Office of Economic Opportunity while some Samoans remain, waving their sticks and thinking: “We’ve done it again! We’ve mau-maued the goddamn white man! He was scared, man!” The flak catcher stands there with his mouth twitching.

Mau-mauing, Wolfe explains, gave you three for the price of one. You didn’t just register your protest, show the white man that you meant business, and weaken his resolve to continue with his oppression, and secondly gain money or influence; you brought fear into his face. The tactic had shown blacks that the white man was terrified of the black man’s masculinity. For generations black boys had been raised to be meek and mild for fear of incurring the white man’s wrath, but the white man had turned out to be easy to intimidate. Mau-mauing was much better than going on a demonstration, which, if it frightened the government, only did so in a general way. Mau-mauing gave you a face-to-face confrontation, which made the white man think: “I’m afraid I’m not man enough to deal with these bad niggers!”

The confrontation ritual was built into the poverty program from the start. The bureaucrats relied on it. Whites who had studied the “urban Negro” knew nothing of the ghettoes. Whenever there was a riot they would call on “Negro leaders” to help quell it, only to find that the rioters didn’t recognize the leaders as their leaders. In Chicago, Martin Luther King had been ignored. When a “black leader” had been sent into Watts, he had been jeered at and had beer cans thrown at him. The Mayor of San Francisco had appeared at a riot along with a black member of the Board of Supervisors only for the brothers to throw rocks at both of them.

You can buy Jim Goad’s Whiteness: The Original Sin here.

Thinking that the riots must be being organized by the gangs, the bureaucrats had sent ex-gang leaders in to liaise, but the ghettoes were so lacking in organization that the former gang leaders could find no one to liaise with. And so, to discover who the key black figures were, the bureaucrats waited to see who turned up to confront the staff at the Office of Economic Opportunity. This had been standard procedure since 1968. The mau-mauers would be there because, whereas to get a job in the post office you had to fill out forms and pass the civil service exam, to get into the poverty scene you only had to do a bit of mau-mauing. If you made the flak catcher’s mouth twitch, your application was approved.

Mau-mauing usually put whites in no physical danger. For the brothers, it was pretty much a game. They didn’t want to hurt anyone, because then they wouldn’t get whatever was being handed out, be it jobs, money, or political influence. The term “mau-mauing” expressed the operation’s game-like quality. It implied: Deep down the white man thinks we’re savages, so let’s do a savage number on him!

When mau-mauing did involve violence, a revolutionary core would be behind it, which might have set itself against the Office of Economic Opportunity or any other institution, such as a university, as when the Black Student Union beat up the editor of the college newspaper during a strike at San Francisco State. The Union was allied with the Black Panthers and had been inspired to take action by Stokely Carmichael. Violence showed that you were serious, and that what you were doing was revolutionary. Most young black men admired the Panthers, who were brave, ripped off the white man, and frightened him like nobody had frightened him before.

The Black Power movement

According to Wikipedia, the Black Power movement began with the aim of creating a black-run economy that would exist alongside the white one, showing that black people could live independently.[2] “Black Power activists founded black-owned bookstores, food cooperatives, farms, media, printing presses, schools, clinics and ambulance services.” If their efforts had succeeded, it would have done wonders for black self-esteem, but they didn’t, so the activists decided to take “immediate violent action to counter American white supremacy,” by which Wikipedia appears to mean white society. In other words, black people tried to emulate white people, and when they found they couldn’t, they attacked them.

Malcolm X was a leading figure in the Nation of Islam, a Black Nationalist movement dating back to the 1930s, until he was assassinated in 1965 by three of its members just as he was about to address a meeting of the Organization of Afro-American Unity. So much for Afro-American Unity. The Black Power movement arose out of his assassination and the riots in Watts of the same year. It was Stokely Carmichael who came up with the term “Black Power,” which was chanted at a demonstration in 1966. The Black Panther Party, which became the movement’s cornerstone, began as an offshoot of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which had itself split from the mainstream civil-rights movement, believing that blacks needed to work alone. The second split occurred because the Panthers had “migrated from a philosophy of nonviolence to one of greater militancy.” Note the language: Unable to tolerate non-violence, they migrated. Where to? A philosophy of greater militancy. They were formed in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale.

In 1967 the Panthers staged armed marches to disrupt the California State Assembly. In 1968 another Black Power group, the Republic of New Afrika, was founded, looking to create a black country in the southern United States. Before dissolving after a few years, it engaged the police in a shootout in Cleveland, Ohio; meanwhile, the Panthers engaged the police in a shootout of their own at a Los Angeles gas station. Both events were followed by riots. By this time Huey Newton had been arrested for the murder of a police officer.

In 1969 the Panthers were involved in many gunfights with the police, as well as one with other Black Nationalists. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers was formed in Detroit, supporting labor rights and black liberation. Wikipedia does not explain why it mentions “labor rights.” Was anyone trying to stop black people from working? One also wonders what the writer thinks black people needed to be liberated from.

In 1970 Stokely Carmichael and other Black Panthers discussed ways of resisting “American imperialism.” It is not clear where they thought the American empire was located. Perhaps they saw it as existing within America, which maintained black people as a subject class. Former Panthers created the Black Liberation Army to pursue violent revolution. Again, Wikipedia doesn’t say from what it sought liberation. But the first thing it did, or was believed to have done, was plant a bomb in a San Francisco church full of mourners attending a police officer’s funeral.

So far, the story of Black Power is hardly one of peaceful souls striving to obtain anything worthwhile, or indeed anything black people did not already have. It is rather a story of rebels without a cause who loved murder and were unable to organize themselves or unite.

In 1971 a group calling itself the Black Revolutionary Assault Team bombed the South African consulate in New York. Differences between Huey Newton and his co-leader Eldridge Cleaver caused the Panthers to split into two factions which fought each other, resulting in a series of assassinations. Five Black Liberation Army members shot two New York City police officers, after which three of its members murdered a policeman in San Francisco. Huey Newton then went to China to learn about Maoism. During an attempted prison escape, a Black Power “icon” named George Jackson killed seven hostages before being killed himself, which led to the Attica Prison uprising, ending in a bloody siege. Black Liberation Army members killed a police officer.

Wikipedia goes on to say that in 1972 the Black Liberation Army assassinated two police officers in New York — in retaliation, they said, for the deaths of prisoners during the Attica prison riot. Five of its members hijacked an aircraft and lost the $1 million ransom they had been promised when the plane landed in Algeria. In 1974 Huey Newton fled to Cuba when accused of murdering a prostitute. In 1975 the George Jackson Brigade was formed, which in the next two and a half years robbed at least seven banks and detonated about 20 pipe bombs in government buildings, power facilities, and the premises of companies accused of racism.

In 1977 Huey Newton returned from exile, his replacement as leader resigned, and the Party fell apart. Three members of the Black Liberation Army were said to have opened fire on state troopers in New Jersey after being pulled over for a broken taillight. One Liberation Army member was killed, as was a state trooper. Another Liberation Army member, a woman, was found to have committed both murders and was also charged with kidnapping, assault and battery, and bank robbery.

Wikipedia tells us that the Black Liberation Army was active until 1981, when some of its members killed the guard of a bullion truck and two police officers. Several other members were subsequently arrested in connection with a bombing campaign against commercial and government buildings, including the United States Senate. In 1984 two members of an associated organization were arrested at a warehouse in New Jersey, where 200 sticks of dynamite, 100 cartridges of explosive, and 24 bags of blasting agent were found. The Army’s last bombing, in 1985, was of the Policemen’s Benevolent Association in New York City. A New Black Panther Party was formed in 1989, the year Huey Newton was killed by a member of the Black Guerrilla Family, but doesn’t seem to have come to much.

You can buy Spencer Quinn’s novel White Like You here.

The Black Panthers were always keen on education, says Wikipedia. They found fault with the existing education system, which didn’t teach black people their role in present-day society. What the Panthers thought black people’s role in present-day society was, Wikipedia doesn’t say. Presumably they didn’t see it as being the same as everyone else’s role in present-day society.

Also according to Wikipedia, the Black Power movement was devoted to empowering black Americans to claim their freedom. It doesn’t say what freedom black Americans lacked. Whatever this freedom might have been, however, it was only natural for the movement to claim it by killing police officers and planting bombs, Wikipedia suggests.

It goes on to say that the movement took a “major interest in creating and controlling its own media institutions.” “Most famously,” the Black Panthers produced the Black Panther newspaper. Wow! They produced a newspaper! But are we even sure that this was produced by black people rather than by Jews, who know how to produce newspapers and created most “Black Power” educational initiatives, as well as founding most “black” organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People? For example, a leading figure in Black Power education was Herbert Kohl, the Jewish author of On Teaching.[3]

Afrocentrism

The 1970s and ‘80s saw the rise of Afrocentrism, as expounded by Dr. Frances Cress Welsing in her theory of “Color Confrontation and Racism (White Supremacy)” (1970), which said that whites were albino mutants. As G. J. Krupey put it, she saw them as melanin-deficient misfits who were “driven into exile from Africa by their disdainful, melanin-enriched parents” before finding refuge in Europe, where they stagnated in savagery until the Greeks stole civilization from the Egyptians, thus making a start for Europe.[4] She took it that the Egyptians, being African, were black.

Her theory was followed by the infamous Portland Baseline Essays, written by black academics in the 1980s, who like her took the ancient Egyptians to be black. “Egypt was a Black African Society,” wrote one contributor, which meant that “the art forms and architecture we relate to Egypt are in fact forms of Black art.”[5] Having credited Egyptian civilization to black people, the essayists embellished it, as with the claim that the Egyptians might have developed electrochemical storage batteries for use in electroplating technology through “their study of electric eels in the Nile River along with their understanding of the basic principles of chemistry.” According to these scholars, the Nile was of extraterrestrial origin. The oceans came from water-laden micro-comets. Moreover, the Egyptians had airplanes. A bird effigy in Cairo Museum was seen as a model of a glider, which was taken to prove that the ancient Egyptians, and hence black people, had constructed aircraft, which they used for travel and recreation.[6]

Starting in 1989, the Portland Baseline Essays were used as teaching material in schools in many major American cities, which thereby acquired a “multicultural curriculum.”[7] One essayist stated that Beethoven was black, by the way.

If one may correct the essayists about black people’s record as architects and technologists, when white people first reached sub-Saharan Africa they found no two-story buildings or buildings made of stone — only mud huts. As for technology, Africans had invented neither the wheel nor even an oil lamp to show them the way in the dark.

The rise of Afrocentrism coincided with that of “black psychology.” The primary consultant to the Baseline Essays project was Dr. Asa Hilliard, a member of the Association of Black Psychologists, who “argued that to repair a collectively damaged black psychology it would be necessary to destroy ‘Eurocentrism’ and its ‘white values’ of rationality, order, and individualism.”[8] It is surprising that as a psychologist Dr. Hilliard failed to see that he was only using the idea of the damaged black psyche to rationalize an attack on white culture that he wanted to make anyway. He should have been able to see that no one damaged the black psyche, which just happens to differ from the white psyche, especially in having more animosity to people of other races. Nor does he seem to have realized that he was implying that black people were irrational and disorderly.

Conclusion

Tom Wolfe’s essay reminds us that black people have been using violence, or the threat of it, as a means of extortion for many decades. Nor was this motivated by any legitimate grievance. It was the same with the Black Power movement. Both prefigured the Black Lives Matter disturbances of recent years, which presumably would not have occurred if white people had showed more spine.

As for Afrocentrism, it, too, is still with us. In 2021 a headline read: “Black History Month website brands white people ‘genetically defective descendants of albino mutants.”[9] It is suggested today more than ever that black people were always great technologists. They are said to have invented the electric light bulb, the cell phone, and — decades before the internal combustion engine came along — the spark plug. A recent book by a black man states that Africans reached America in 40,000 BC, that there was a black Roman Emperor, and that black people once ruled the world.[10]

So keen are the politically correct to demonstrate their belief in essential racial equality that for decades they have rushed to make incompetent and vicious black people professors, resulting in someone such as Professor Brittney Cooper of Rutgers University telling a conference: “We gotta take the white people out!”[11] According to her, black and brown people cohabited in America “being brilliant [with] libraries and inventions and vibrant notions of humanity” long before “raggedy and violent and terrible” white people got there. It is common to hear such professors calling for white people to commit mass suicide or be made victims of a holocaust or other form of genocide.[12]

White authorities continue to collude. Joe Biden congratulated the organization behind the conference where Brittney Cooper spoke, saying that conversations such as those were essential to bring us closer to the promise of equal rights and equal dignity for all.[13] Is it possible for a race to humiliate itself more than we are doing?

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] Tom Wolfe, Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers (New York: Bantam Books, 1999), first published in 1970. The paraphrased text is from pages 102-08.

[2] Wikipedia, accessed 2022, “Black Power movement.”

[3] Herbert Kohl, On Teaching (New York: Schocken Books, 1977).

[4] G. J. Krupey, “Making Black Supremacist NOIse” in Peter Collier & David Horowitz (eds.), The Race Card: White Guilt, Black Resentment, and the Assault on Truth and Justice (Rocklin, Calif.: Forum-Prima, 1997), 139-148.

[5] K. L. Billingsley, “Afrocentric Curriculum” in The Race Card, p. 131.

[6] Erich Martel, “ . . . AND HOW NOT To: A Critique of the Portland Baseline Essays,” American Educator, Spring 1994.

[7] Billingsley, 128-138.

[8] Billingsley, 130.

[9] Image from a news site posted to Telegram by Mark Collett in October 2021.

[10] A reviewer found this book, by the former West Indian cricketer Michael Holding, to be “full of the most shocking errors and what look like deliberate falsehoods” (History Debunked, October 30, 2021, “A review of the book Why we Kneel, How we rise, by Michael Holding (Simon & Schuster, 2021).”

[11] Vincent James, November 2, 2021, “BLACK PROFESSOR CALLS FOR WHITE GENOCIDE: ‘WE GOT TO TAKE THEM OUT.’”

[12] Mark Collett shows headlines from the American press between 2015 and 2017 reading: “Professor tweets that white people should commit mass suicide”; “Trinity College professor calls white people ‘inhuman’: ‘Let them f-ing die’”; “All I want for Christmas is white genocide”; “USC Professor Calls For Holocaust Against All White People”; “Professor: ‘Some White People May Have to Die’ to Solve Racism”; and “White Professor calls all white people to mass suicide over slavery” (Mark Collett clips, October 7, 2020, “Racism’s New Anti-White Definition — Mark Collett.”)

[13] The Root, September 21, 2021, “The Root Institute 2021: A Special Message From President Joe Biden.”

Three%20Episodes%20from%20the%20History%20of%20Racial%20Politics

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Fear of Calling a Spade a Spade

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 3

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

Are Whites Finally Waking Up?

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

4 comments

I hardly can wait for the Sleeping Giant to awaken, so we can get them off our back, and all the other Lilliputians too.

Agreed. By the way, Space Vixen Trek Episode 17 arrived today. I wasn’t sure while book-browsing on amazon if this was Rainbeau Albrecht’s but I picked it up anyway. Is there a chronological order to trek the madnesses available or any trip at random will suffice? Good day.

For the most part, the numbering is not sequential, but rather based on some obscure numerology. The exception is that Episode 18 actually will follow Episode 17. Whenever I finish it, that will be a mashup of a famous Greek epic with a horrid 1960s TV series.

The other stories have remarkably similar characters but some are effectively in another timeline, and each showcases a different genre. Episode 13 (where I make fun of just about every major religion) is followed by Episode 0 (the fantasy game that turns out to be real) and there are two sequels in the pipeline. I should note that Episode 17 is the most political of all, by far.

“Sleeping Giant”, eventually we will find out, won’t we.

”…[S]o we can get them off our back”. There is ONLY one solution, 100% separation in perpetuity. Our enemies r never the problem, we r our problem due to how we think. We need to cease in the belief of not being able to live without non-Europeans, &, trying to help every other race. Unless we break free, our children’s future will b bleak.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.