2,548 words

Recently I had dinner with an Englishman who could have stood in as “a good man from the Shire” sort of character on an episode of PBS’ Masterpiece Theater. I raised the question of Brexit: good or bad? His response was very negative. He then went on to describe the many problems of Britain’s exit from the European Union.

White advocates, both in the United States and Britain, seem overall to be in favor of Brexit, but Brexit isn’t a central issue for pro-white activists. The central issue is the “civil rights” fraud and population displacement. Nonetheless, white advocates must be knowledgeable of the complexities and nuances of economics and trade policy. So, was Brexit good or bad? What got the British into the European Union and what got them out of it?

England & Europe

The pattern of British policy towards Europe began to take a recognizable shape during the reign of Henry VIII. The pattern goes roughly like this: Britain’s most important trading relationship is with the Low Countries. Any Continental power that interrupts this relationship becomes the mortal enemy of the British. (An example of this is the British going to war against Germany to “restore Belgian neutrality” in 1914.) The Portuguese and British likewise have a similar relationship, but Portugal is rarely invaded by a Continental Power.

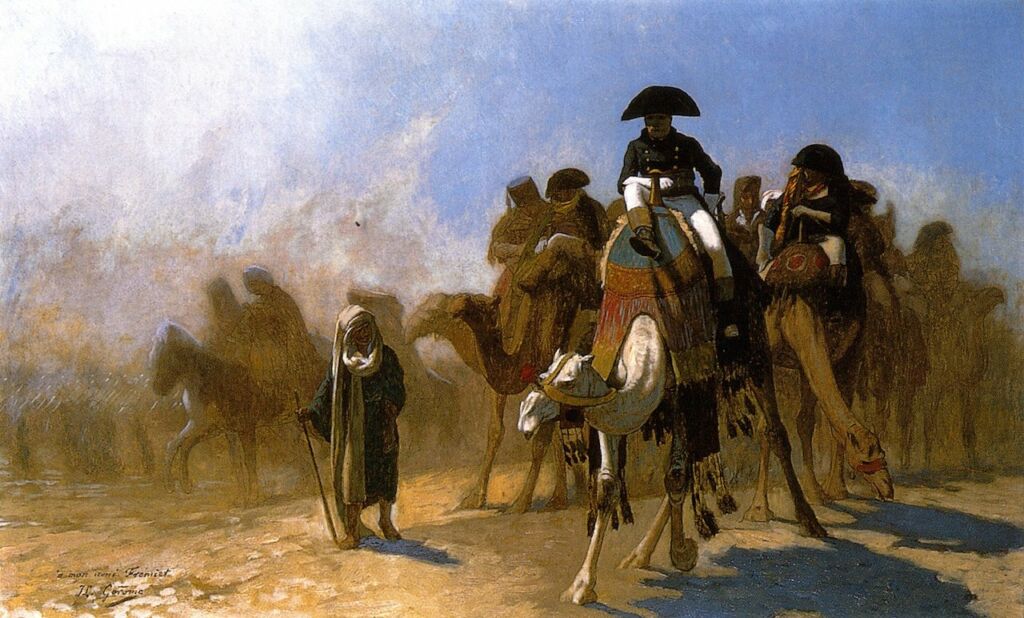

Napoleon sought to make the Continent of Europe an anti-British common market. The policy’s failure led to the 1812 French invasion of Russia.

Meanwhile, the British always support the second-most powerful nation on the Continent against the most powerful one. This is called the balance of power strategy.

The balance of power strategy was used by generations of British statesmen. Conflicts between Britain and the Continental power following this strategy have played out repeatedly in the same pattern. This is especially apparent when looking at the Napoleonic Wars alongside the Second World War. In both cases, the Royal Navy destroyed the navies of neutral nations: the Danish fleet at Copenhagen in 1801 and the Vichy French fleet in North Africa in 1940. Egypt was also fought over during both conflicts. Britain subsidized the armies of Continental allies: Austria during Napoleon’s time, and the Soviet Union in the Second World War. Hitler invaded Russia for the same basic reasons that Napoleon had.

As long as the rivalry on the Continent was between France and Spain, this policy worked, but when other nations, such as Germany and the Soviet Union, rose to prominence, the flaws in the balance of power became apparent, and they must be illuminated.

The flaws in the balance of power policy are, firstly, that it substitutes a healthy pursuit of common interests among states with tortuous attempts to undermine any state which attains a leading position while failing to take into account the attitude of such a state towards the United Kingdom. Secondly, it demands otherwise inexplicable shifts in position when it becomes evident that one state has been overestimated or another underestimated. (Thus, Oceana has “always” been at war with Eurasia.)

With Brexit, the British created a situation where a united Europe controls the economic policies of the Low Countries and Portugal. A repeat of the balance of power strategy seems impossible now, since the European Union has grown up naturally rather than on the bayonets of an invasion force such as the Grande Armée.

It Looks Easy in the Spring: The European Union Heads East

You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died by clicking here.

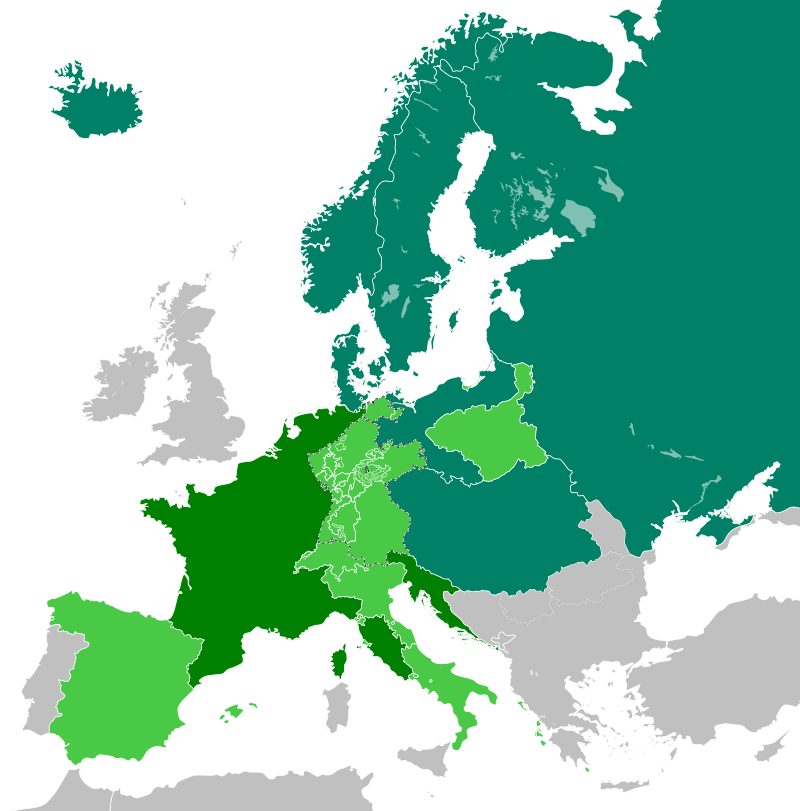

The European Union arose out of a post-war customs union in Western Europe, the European Coal and Steel Community. The European Economic Community (EEC) was established in 1957, and Britain joined it in 1973. In 1993, the EEC was replaced by the European Union and a common currency was established: the Euro. Within a decade, it was in common use. Britain kept the British Pound. Meanwhile, the European Union developed and expanded after the end of the Cold War to include the former Eastern Bloc states such as Poland, Hungary, the Baltics, and much of the Balkans, as well as Cyprus.

The Euro has not been the bloc’s main problem, though. The European Union’s key policy is the free movement of people — especially workers. As long as the EU was confined to Western Europe, this was not an issue, but after the Cold War ended, the EU went east. The further east into Europe a Western European political system expands, the greater the complications. Once the EU gained Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria, it was only a matter of time before something broke, and what broke was England’s relationship with the EU. To explain, Britain is the jobs producer of Europe. Eastern Europeans, many highly skilled in the blue-collar trades, started to displace the English working class. The resulting resentment crossed political parties and social classes.

Debt & Migrants

The British relationship with the European Union received blows from several more crises. The first was the debt crisis. In 2008, the real estate bubble in the United States popped and the economic shock waves quickly enveloped Europe. Nowhere was the problem greater than in Southern Europe, especially Greece.

The crisis was shored up with government bailouts and austerity measures, but it reinforced the Eurosceptic wing of British Prime Minister David Cameron’s Conservative Party, as well as the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), whose primary aim was to get the UK out of the EU.

Then came the migrant crisis that began in 2015, which was caused by several factors. First, the Israel lobby in the United States and Europe caused the white nations of the West to support savage terrorists, misnamed “moderate Syrian rebels,” against the effective and legitimate government of Syria. This created thousands of displaced Syrians who were quickly joined by other Third World grifters. Then the Israel First elite in the French and British governments supported the toppling of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, which led to further migrant flows from Africa.

Then the central core of the EU, France and especially Germany, failed to defend the bloc’s Greek and Italian frontiers from incoming migrants. European diplomats likewise failed to cajole the various nations of the Middle East into accepting the migrants themselves. All of this occurred in a media environment filled with virtue-signaling and demands for sympathy. On the night of November 13, 2015, Mohammedan terrorists, some of whom were migrants from the recent wave, staged a vicious attack upon the Bataclan Theater in Paris. The pieties and virtue-signaling of the EU’s elite that had supported the migrants came to a crashing end.

The Bataclan Massacre was the direct result of the European Union’s failure to keep out migrant invaders.

David Cameron

David Cameron of the Conservative Party became Prime Minister of Britain in 2010. He employed a strategy of using referendums to put contentious issues to rest. In 2013, he had the Falklands Islands hold a referendum on the matter of their status; they voted overwhelmingly in favor of remaining a British Overseas Territory. In 2014, Cameron determined that he needed to hold a referendum on Scottish independence. The Scots voted against independence.

In 2015, Cameron and the Conservative Party won a general election partially on Mr. Cameron’s promise to hold a referendum on the UK’s membership in the EU. Cameron was looking to end a series of rebellions from the Eurosceptic wing of his party and eliminate the UKIP threat. The UKIP threat became a full-blown crisis when Douglas Carswell, a Member of Parliament for Clacton, switched from the Conservative Party to UKIP. The EU Referendum itself took place on June 23, 2016 — and the rest is history.

Cameron did not wish to leave the European Union. He had wanted to use the referendum as before: to demonstrate overwhelming support for a particular policy that he favored. In this case, it didn’t work. “Leave” won, and Cameron resigned shortly after the vote.

How “Leave” Won

Chris Grey, a retired professor, has risen to become a top-level blogger documenting Brexit and its aftermath. Professor Grey is hostile to Brexit, feeling it is a self-inflicted economic and diplomatic wound. In spite of this, he has gathered most of the facts of Brexit in as even-handed a way as possible. He has given a blow-by-blow account of what happened in his 2021 book, Brexit Unfolded.

Brexit won for several reasons. The Eurozone and migrant crises were certainly major factors. On top of this, several British governments couldn’t get the immigration numbers down, so housing became more and more expensive. Images of slum houses filled with Romanian workers became commonplace in the media. The EU was rightly blamed.

The “Leave” campaign was also aided by the caliber its leadership. UKIP attracted solid people. There were few gaffes and no media frenzies after some early hiccups, such as some ill-judged Roman salutes. Jacob Rees-Mogg, a pro-Leave Conservative, even wrote a well-received book on the Victorian Era. The pro-EU crowd also attracted quality people, but they never got past being smug elitists who concentrated on making insults rather than doing good work.

Rock ‘n’ Roll artist Bob Geldorf’s “Remain” flotilla was an optics disaster of their side’s sneering and elitism.

Chris Grey writes that:

In the run up to the referendum, it was widely remarked upon that one significant strand of the leave campaign channelled the British fixation with, and often mythologisation of, the Second World War. How big a part it played in the outcome of the vote is impossible to say, but it seems plausible that it was a factor amongst the demographic that voted most strongly for Brexit, the over 50s. This would be not so much people who remember the Second World War — now a relatively small number — but the generation or two who grew up, as I did, in its shadow.[1]

If Brexit does turn out to be a massive self-inflicted wound, it will be yet another consequence of the British and American hallowing of the Second World War.

“Leave” also won because its proponents were able to keep the details of any post-Brexit policy vague. Once Theresa May became Prime Minister, she was faced with questions regarding what to do and how to go about doing it. Three courses of action arose:

- Soft Brexit, or the “Norway option.” This meant remaining a member of the single market and some form of customs union.

- Hard Brexit, or the “Canada option.” This meant leaving the single market but seeking a free trade agreement with the EU.

- No-Deal Brexit, or the “WTO option.” This meant leaving with no trade deal and trading on World Trade Organization terms instead.

Theresa May had a tough time getting Brexit through. She rose through the ranks in Parliament by representing a safe seat for Conservatives in Maidenhead. She took few controversial stances and was often outshined by others in her party. May’s tenure as Prime Minister was successful in that she didn’t polarize the British electorate, but she wasn’t able to manage the fierce politics of her day within her own party and the EU more broadly. After she lost a disastrous general election, her political position was doomed.

Theresa May had a tough time creating an EU exit strategy.

Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty

May was then replaced by Boris Johnson. At this time, it is important to note, the Brexit referendum could have been reversed. Only England and Wales had clearly voted for Brexit. Across the board, those voting “Leave” were only a few percentage points above those voting “Remain.” Critical parts of Britain such as Gibraltar and London voted to “Remain” overwhelmingly. The problem of the referendum can easily be described as the problem of democracy itself, where 51% of the foxes vote against 49% of the geese over what’s for dinner.

The “Remainers” just couldn’t get themselves together in the face of the crisis. It seems likely that the Labour Party’s embrace of trendy Leftist flapdoodles such as announcing one’s pronouns didn’t help the “Remain” cause whatsoever. Chris Grey writes that the “Remainers” were associated

with the supposedly finger-wagging, ‘won’t let us say what we really think’, prissy, moralistic do-gooders. Graduates with ‘Mickey Mouse’ degrees. The Human Rights Brigade. The PC Brigade. The Race Relations Brigade. The ‘girly swots’. The bleeding-heart liberals.[2]

Good or Bad?

Brexit has happened. Chris Grey’s suggestion to EU supporters going forward is to stop calling themselves “Remainers.” The course of action ultimately taken by the British has been a hard Brexit, leaving Northern Ireland within the EU but with no customs barrier between themselves and the rest of the UK. The trouble in Northern Ireland is where, exactly, to draw the border in the new situation. Should it be on land or sea? A hard border in either place is a disaster for Northern Ireland. Thus, so far there is no definite border, and the diplomats have succeeded in putting off the question for now.

So was Brexit good or bad? Without a shadow of a doubt, the huge economic impact of the COVID pandemic have concealed much of Brexit’s impact. There are some things that are clearly troublesome. Shipping British goods to Europe is now more expensive. There is a shortage of truck drivers and trucks. There are supply chain issues and empty shelves. British fishermen have lost out because their fish aren’t being purchased in Europe — even though it seems Europeans aren’t fishing those waters, either, which means the British will have more fish to catch in the future. Also, the ongoing microchip shortage could be partially the result of Brexit.

The closest precedent for Brexit in British history is probably Henry VIII’s break with Rome. All Henry VIII had really wanted was a divorce, but his subsequent break with the Church to make it happen ended up releasing unanticipated and uncontrollable social forces. The dissolution of the monasteries led to monks, nuns, and friars being displaced. There was an ugly rebellion in northern England called the Pilgrimage of Grace as a result. Britain’s relationship with Spain went into a tailspin that led to several wars. But at the same time, capital that had been locked up in religious shrines was distributed to people who made good use of it. England became a world power.

It’s therefore hard to say at this point if Brexit is really good or bad. There are certainly new opportunities to go around. Now every politician in Britain has the chance to get elected based on promises of “frictionless trade” with Europe without having to worry about migrants or bailouts. Supply chains can be rebuilt. The United States and Canada can step in with products formerly supplied by Europe. Young British working class men can learn a trade free from foreign competition, marry a British woman, and have children. Traders in Northern Ireland have the chance to make money from becoming a transition point between the UK and the EU.

Whatever happens, however, Britain’s problems can no longer be blamed on the EU. The British must instead look them in the eye and act.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Notes

[1] Chris Grey, Brexit Unfolded: How No One Got What They Wanted (and Why They Were Never Going To) (London: Biteback Publishing Ltd., 2001), p. 113.

[2] Ibid., p. 210.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

Five Years’ Hard Labour? The British General Election

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

-

Elizabeth Dilling on the Evil of the Talmud

-

Wholesome Escapism: The BBC Farm Series

2 comments

Could signal the end of farming.

Hats off to the British for getting out of the EU superstate. Also the fact that the electorate voted to ‘get Brexit done’ in the election was the second time saying a big solid NO to EU elitists. In Ireland we voted against two separate EU referendums only for our neoliberal globohomo politicians to ignore the results of each referendum by saying they didn’t explain the content well enough and then rerun the referendum to get the desired ‘democratic’ result – total Sham democracy

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.