2,053 words

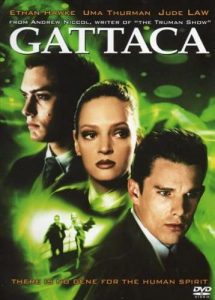

Gattaca (1997) is a dystopian science fiction movie set sometime in the mid-21st century. Mankind is doing a lot of manned space exploration. Genetic engineering and zygote selection have eliminated major and minor genetic problems, from mental illness to baldness. As a smiling black man who works as a eugenics counselor explains to a pair of prospective parents, the children produced by these techniques “are still you, just the best of you.”

In the world of Gattaca, everyone is attractive, clean-cut, and dressed in elegant business suits. They drive cool, retro-looking electric cars, listen to classical music, dine in fine restaurants, and live in multi-million-dollar lofts and beach houses in Marin Country. The space agency, called Gattaca, is headquartered in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Marin County Civic Center building, which will look futuristic even centuries from now.

It sounds pretty utopian to me. But writer-director Andrew Niccol wants to convince us that it is a totalitarian hell.

Gattaca is the story of Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke), whose name could only be more symbolic if they just called him Victor Freeman. Vincent is the guy who is going make free will triumph over determinism.

Vincent is a naturally conceived child in a world in which such births have become rare. As soon as Vincent is born, a blood sample is taken, and his parents are informed that he will likely suffer from various mood disorders and die of a heart attack by the age of thirty. It is a bit heavy to lay on a woman who has just gone through labor, but Niccol wants us to hate these people.

From the moment of birth, Vincent is treated as an invalid. In fact, the whole society is constructed around the distinction between the genetically Valid, namely the engineered, and In-Valid — get it? get it? — namely, those conceived naturally. The Valids are privileged, and the In-Valids are oppressed. Vincent’s mother coddles him and doesn’t want him to play outside. His father tells him not to dream about going into space with a bum ticker. Both parents also invest more emotionally in their younger son, Anton, who was genetically selected and tweaked before birth.

Okay, let’s pause here for a moment to let this sink in. For a society that values intelligence, there’s something rather stupid about this.

First, the idea of a caste system between Valids and In-Valids makes no sense. A society that values eugenics values science and objective merit. Such a society would know that among the so-called In-Valids, you would find people of superlative intelligence, health, beauty, creativity, and other excellences, at pretty much the rate that we find them among naturally conceived people today. Thus the idea that In-Valids would be subjected to crass discrimination and oppression is simply an attempt to brand eugenics as an arbitrary, evil form of discrimination, like “racism” against black people (which isn’t that unreasonable either, to be honest, but white nationalists prefer racially homogeneous societies where such discrimination is made impossible).

Second, there’s no doubt that genes determine our potentials. And, as the Director of the Gattaca space agency, played by Gore Vidal, says, “Nobody exceeds his potential. If he does, it simply means we did not gauge it accurately to begin with.” This is true. Our potential is what we can do. What exceeds our potential is what we can’t do. We can’t do what we can’t do.

But there are several factors being left out here.

You can buy Return of the Son of Trevor Lynch’s CENSORED Guide to the Movies here

Our potential is the outer limit of what we can do. But how many people get anywhere near those outer boundaries? Thus knowing potentials is not the same as knowing life outcomes. Our genes aren’t the only things that determine our potential. You might have genes to make you a star athlete, but you don’t have the potential to do that if you are paralyzed in a car accident.

Why are these people so cocksure that they can gauge people’s potential accurately? In Gattaca, Vincent, the Director, and Vincent’s love interest Irene (Uma Thurman) all do things that they “can’t” do, which means that their potential has not been gauged accurately. But a society that values science and objective merit would not permit such smugness and the injustices and waste of resources it would inevitably cause.

In the society of Gattaca, genetic testing has basically eliminated the job interview, the curriculum vitae, and the letter of recommendation — as if your genes are your only qualification, regardless of the maturation, education, experience, and character that you have acquired over your lifetime.

Granted, one can weed out some applicants based on genetic grounds. The lame, the halt, and the blind can’t do certain jobs. Astronauts can’t have weak hearts. Surgeons can’t be blind. Conductors can’t be deaf.

But once you eliminate gross disabilities, other factors beyond genetic potential become relevant. For instance, some people who can do a job may not want to. A society that overlooks such factors is stupid, not smart — scientistic, not scientific.

Let’s look at the case of Vincent. Vincent is apparently highly intelligent, but he is told that he is fit only for manual labor because of — get this — his weak heart. Yes, it is that stupid. In the real world, of course, a highly intelligent young man with a weak heart might be shunted into the precise job that Vincent ended up in: a programmer at the space agency.

If Vincent really had a bad heart, no amount of training could fix it. In fact, such training could kill him. But one has to wonder: Wouldn’t the world of Gattaca also have the technology to fix heart defects or simply replace defective hearts with lab-grown transplants?

No matter how much Vincent dreams of going into space, he can’t be an astronaut if he has a bad heart. That is not an unreasonable or tyrannical requirement. Astronauts have to deal with enormous stress. An astronaut who dies of heart failure may cost the lives of his fellow crewmen. Astronauts are also very expensive to train.

Vincent, however, decides that he is going to cheat his way into space. We are supposed to think this is inspiring, but it is deeply unethical. Vincent buys the identity of Jerome Eugene (get it?) Morrow, played by Jude Law. (Two years later, Law’s identity is simply stolen in The Talented Mr. Ripley.) Eugene is genetically Valid. He has a stratospherically high IQ and is a phenomenal athlete. Or at least he was until a botched suicide attempt left him paraplegic. Jerome is now a self-pitying drunk.

Jerome had a much better genetic hand dealt him than Vincent, but he played it poorly. Vincent had a worse hand, but he plays it well. Of course, how well we can play our cards is also, arguably, a genetic card that is dealt us. But how well we actually play them is another thing. No matter how comprehensive and fine-grained genetic determinism may be, I see people exercising more or less agency, more or less wisdom, in making something out of what nature makes them into. And as for those who think they can predict those results with a blood test, well, something in my blood tells me we would be fools to believe them.

To pass himself off as Jerome, Vincent needs to go to ridiculous lengths, because the world of Gattaca is a Kafkaesque police state. Vincent can’t just get a fake ID, because one’s genes are one’s ID. When Vincent walks into work every day, he doesn’t swipe his lanyard. His finger is pricked and his DNA analyzed. (Sounds unsanitary.) Vincent also has to worry about leaving hair and skin flakes at his desk, for apparently these are collected and analyzed as well. (Sounds insane.) Then there are the urine tests. Thus Vincent needs a constant supply of Jerome’s hair, skin, blood, and urine. Every morning, he has to put blood into false fingertips and strap bags of urine to his leg before going to work.

One wonders if he would have given up if they had started requiring stool samples.

The world of Gattaca is an idiocracy, not a meritocracy, eugenics as viewed by the dysgenic. We’re supposed to find it chillingly dystopian, and just because it is stupid, it doesn’t mean it’s implausible. Communism was quite stupid too, after all, but it reliably produced dystopias all over the globe.

Aside from its ludicrous dystopian elements, Gattaca does put its finger on a deep human truth that has real dramatic potential. The society of Gattaca is really quite bourgeois, meaning that everyone operates on the assumption that the best life is a long and comfortable one, and the worse thing possible is a short life, especially if one meets a violent end.

In more heroic ages, such a mentality was disdained as worthy only of slaves. In terms of Plato’s psychology, bourgeois man is ruled by his desires, meaning that desire wins out when it conflicts with other motives, such as honor. Heroic man, by contrast, is ruled by thumos — the part of the soul that responds to honor and seeks adventure and even conflict — so that when thumos conflicts with desire — even the desire for self-preservation — thumos wins out.

Vincent is told that he will live a short life and thus should take it easy, whereas he concludes that he needs to up life’s intensity. Vincent and his brother Anton play chicken by swimming out into the ocean. The chicken is the first one who turns back. Anton is engineered to be a superior athlete. He is confident that he will always win, and he always does, until one day Vincent beats him. Then, armed with a new confidence, Vincent runs away from home to fulfill his dreams.

Years later, Vincent meets his brother again and explains how he won: When he swam out, he did not save anything for the trip back. In other words, he was willing to risk death for victory. Their game of chicken was a reenactment of Hegel’s image of the beginning of history: the struggle to the death over honor.

Even though Vincent did not save anything for the trip back, he still made it back, because there’s a difference between our objective limits and our subjective sense of what those limits are. We usually can do more than we think we can, but we learn that only by disregarding what we — and others — think our limits are. Doing so requires risk, sometimes mortal risk, sometimes merely risking other people’s disapproval. But the possibility of dying should be a small thing compared to the certainty of never really living if we don’t try.

Not saving anything for the journey back also explains Vincent’s desire to go into space, heart condition or not. He wanted to get out there. He wasn’t concerned with coming back.

I will say no more about Gattaca’s plot, save that there’s a whole lot more dumbness for you to discover if you are curious, including a number of completely pointless scenes and plot twists.

Gattaca may be dumb, but it is beautiful. The cast, clothes, cars, music, sets, and production design are all first-rate. I especially loved the scene in which Vincent and the rest of his crew enter their rocket ship dressed in elegant business suits.

Even though Gattaca is crude anti-eugenics propaganda, it probably didn’t do much harm. The movie was pretty much a flop, so few people saw it. Moreover, it is so dumb that it could only convince dumb people of dysgenics, and dumb people already practice dysgenics.

Beyond that, Gattaca also had eugenic effects. Co-stars Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman met on the set, and their roles might have gotten them thinking. Not only are they good-looking, but they are also highly intelligent and descend from elite families. They married in 1998 and had two good-looking kids.

For eugenicists, breeding well is the best revenge.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Beautiful%2C%20But%20Dumb%3A%20Gattaca

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 1: Nowa Prawica przeciw Starej Prawicy

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Civil War

-

Psychoanalyzing the Natives: The Big Lift

-

Made in Britain: The Rise and Fall of Skinheads

-

Dune: Part Two

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 574: James Tucker on George Grant and Nationalism

8 comments

Nice! Also, f_ the movie’s stupid pseudo-philosophy!

https://counter-currents.com/2016/10/gattaca-is-wrong/

I read a great article about the movie on this website a while back, by Rocketmensch.

Why do you think a society based on a superficial artificial inorganic method of eugenics (picking a suitable mate and encouraging certain people not to breed is organic eugenics) that ignores the spiritual wouldn’t value scientism over science…the latter hardly better as a thing to worship (e.g. IQ fetishists) in the absence of god in modernity, which is why eugenics became a conscious system in the first place.

The spiritual really is not the issue.

This is a portrayal of a society that supposedly believes in genetics and human quality distinctions and has somehow forgotten that high-quality humans happen even without conscious eugenic measures.

I think discrimination against naturally conceived people in the film was supposed to work like discrimination against out-of-wedlock people in olden days. The idea is that it helps reinforce the social norm, in this case reproduction by embryo selection.

Of course we could think up a more refined and less unfair system of incentives and punishments.

But then there would be no plot and no movie.

And no anti-eugenic propaganda.

In the world of Gattaca, discrimination against invalids is illegal, but everyone does it. This is an inegalitarian society with an egalitarian legal structure as a disguise.

In an ideal egalitarian state, such as Sparta in its better days, all men should be equal, or “similar,” luxurious displays of status should be minimized, and the competition for honors should be open. (The Spartan constitution had democratic elements.) Women, of course, are not equal to men, and out-groups such as Helots and barbarians have no place in this system of equality, which is based on martial brotherhood and common genetic interests.

This corresponds to ancient white intuitions about how things should be. This sort of system adds up. All men risk the same thing in battle, which is death, and groups having sufficiently common genetic interests to sustain self-sacrificing martial solidarity also probably have similar capacities among their members. This sort of system does not need to disguise itself, or hide itself from the sort of moral judgement that white men have an ancient tendency to apply. Men of frank character can feel at home in such a society. It is not Kafkaesque at all.

It is different in strongly inegalitarian societies, including those where the people at the top, like the British royal family, believe in “good breeding.” Here, it is a problem to exclude the vast majority of the truly talented people from the competition for honors, power, and reproductive resources. That is because if you have a high quality general population, natural variation means that the high-performing best members of it will outnumber the top members of a small pure-bred elite.

A system like this calls for deceit, and deceit’s helper hypocrisy. It also answers Carl Schmitt’s vital question “who is the enemy?” by saying, “in the first place, the enemy is the inferior orders of our own race and nation.”

(And in order to hold down or destroy the main enemy, that is the inferior orders of one’s own race, one may enter into alliances with fellow-elites, such as those high-IQ Asians, those articulate Hebrews, and so on. This is what we see people at the top doing. That is a reason to mistrust the inegalitarian impulse.)

Let Prince Andrew, who is so very honorable that he is perhaps too honorable, stand for the top of an inegalitarian society based on good breeding. On various tests, he may indeed be superior to the average commoner. He certainly has more military training and experience than the average Englishman. But would well-bred “elites” like Prince Andrew show up well in continuous open competition with the likes of Captain James Cook or General William Slim, white Englishmen rising from totally undistinguished status on pure merit? No.

Gattaca is the cartoon version, made pretty and easy for us to understand. But it is also a look at a white society where the well-bred “valid” people at the top can’t stand and hypocritically won’t allow fair competition from the best of the common people. (Especially competition for the opportunity to do what white men love best to do, which is explore.)

In that aspect, the system isn’t unrealistically stupid. It’s an aspect of what we see.

I like Gattaca because it isn’t just a morality tale about us, the upwardly striving goodies, beating demonized white “elite” baddies.

First, the competition is between brothers — literally brothers, in one case. Family still counts, and the tension between the valid brother and the invalid brother does not annul their bond. Anton wants to keep Vincent out of trouble, not destroy him.

Second, as Trevor Lynch points out, this dystopian society isn’t evil, just flawed. People are looking good, living well, and trying to do good things like explore space and create new high culture. If a society genuinely pursues the good, but cheats as to who gets to be the hero of the story, things can be much worse than that. This fictional eugenic dystopia is better than real life dysgenetic governments importing Somalis and Pakistanis into our neighborhoods to destroy our cultures and end our generations.

Third, I like how Vincent Freeman and Jerome Eugene Morrow trade places. Vincent starts as the one who is at a physical disadvantage but is working on a sort of triumph of the spirit. Jerome ends as the physically defeated and destroyed double, but through his unselfish and almost brotherly love of Vincent, and through his intelligence and will, he gets a sort of spiritual triumph. At the end, Jerome is not much more defeated than a runner who passes the baton to another runner to finish the race. I don’t think this part of the story is played up nearly as well or as strongly as it should have been, but it’s there and it’s nice.

I find this more reasonable than, say, some magic Negro sacrificing himself for the success and happiness of a member of an alien race against which his own race has grievances. Vincent and Jerome have a lot in common. They can work together. They can keep their latent problems latent.

This too is something we can see in history. Pure and unforgiving “levelers” hardly ever create the egalitarian utopias they want. We like hierarchies. They come into being regardless of our plans. We do best to accept that. There will always be a need for us to reach across divides and work together.

The movie is really beautiful and dumb.

I think that they lose their main argument in the treadmill scene,, Vincent just can’t follow the others, his trip to space is based on a fraud.

From what the movie itself presents he will not be able to endure the mission, that is, the selection worked

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment