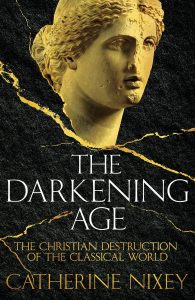

Catherine Nixey

The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018

Catherine Nixey’s The Darkening Age is a powerful and highly readable account of the Christian destruction of classical antiquity. It is certainly not without flaws, but it offers hard-hitting and concise rebuttals to widespread myths surrounding the history of early Christianity.

There are surprisingly few books on this subject. The only comprehensive account of Christianity’s crimes against the pagan world is Karlheinz Deschner’s ten-volume Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity), which has never been translated into English. The main reason for this, of course, is that Christianity dominated intellectual life in Europe for more than a millennium, and history is written by the victors. Nixey points out that until 1871, Oxford required all of its students to be members of the Church of England. Few ventured to criticize Christianity in such an atmosphere.

The Darkening Age is (as far as I know) the only work of popular history on the subject of Christian violence against pagans. Unlike Deschner’s work, it is not a dense, scholarly tome but rather a polemic written for a popular audience. Nixey’s prose is bold and lively, and she makes no pretense of impartiality, as she makes clear in her Introduction:

This is a book about the Christian destruction of the classical world. The Christian assault was not the only one – fire, flood, invasion and time itself all played their part – but this book focuses on Christianity’s assault in particular. This is not to say that the Church didn’t also preserve things: it did. But the story of Christianity’s good works in this period has been told again and again; such books proliferate in libraries and bookshops. The history and the sufferings of those whom Christianity defeated have not been. This book concentrates on them.

Nixey acknowledges that the Catholic Church did indeed preserve Classical manuscripts and works of art. She praises “the Christianity of ancient monastic libraries, of the beauty of illuminated manuscripts, of the Venerable Bede.” However, as she points out, much more was destroyed than was preserved. That the Church preserved a fraction of the total body of Classical manuscripts and art does not change the fact that Christianity’s triumph was made possible in large part by the destruction of paganism.

Christian monks are often credited with preserving Classical texts. Less often acknowledged is that monks themselves were also complicit in the destruction of Classical Antiquity. These included St. Benedict, the famed founder of the Benedictine Order. Upon arriving at Monte Cassino, where he established his first monastery, his first act was to destroy a statue of Apollo along with an altar dedicated to him, upon which he built a chapel dedicated to St. John the Baptist. He went further, “pulling down the idols and destroying the groves on the mountain . . . until he had uprooted the last remnant of heathenism in those parts.”

St. Martin of Tours, a monk and bishop to whom the oldest monastery in Europe is dedicated, destroyed pagan shrines and statues throughout the Gaulish countryside. A line in the Life of St. Martin reads: “He completely demolished the temple belonging to the false religion and reduced all the altars and statues to dust.” Exaggerations abound in hagiographies, naturally, but it is telling that both Benedict’s and Martin’s hagiographers saw temple destruction as praiseworthy and gushed over their escapades.

Bands of Christian monks were known to go on similar rampages in Syria. The book opens with a description (drawn with some poetic license) of the overthrowing of Palmyra in 385 CE. The altar of the Temple of Al-Lat (a Near Eastern goddess associated with Athena) was destroyed, and the statue of Allat-Athena was decapitated and had her arms and nose chopped off. Nearly two thousand years later, ISIS finished what their monotheistic forebears had started by demolishing temples and statues at Palmyra, including what remained of the statue of Athena.

The Greek orator Libanius described the destruction of temples in Syria: “These people hasten to attack the temples with sticks and stones and bars of iron, and in some cases, disdaining these, with hands and feet. Then utter desolation follows, with the stripping of roofs, demolition of walls, the tearing down of statues, and the overthrow of altars, and the priests must either keep quiet or die . . . .”

Thus the destruction of temples and works of art was not the domain of lone wolves and isolated lunatics. It was enacted and abetted by Christian monks, bishops, and theologians, some of whom were later canonized. Even St. Augustine once declared “that all superstition of pagans and heathens should be annihilated is what God wants, God commands, God proclaims!” John Chrysostom delighted in the decline of paganism: “The tradition of the forefathers has been destroyed, the deep rooted custom has been torn out, the tyranny of joy [and] the accursed festivals . . . have been obliterated just like smoke.” He gloated that the writings “of the Greeks have all perished and are obliterated.” “Where is Plato? Nowhere! Where is Paul? In the mouths of all!”

Chrysostom encouraged other Christians to ransack people’s houses and pry them for any sign of heresy. This tactic was also embraced by Shenoute, an Egyptian abbot who is now considered a saint in the Coptic church. Shenoute and his gangs of thugs would break into houses of locals suspected to be pagans and destroy “pagan” statues and literature. In his words, “there is no crime for those who have Christ.” A fifth-century Syrian bishop advised Christians to “search out the books of the heretics . . . in every place, and wherever you can, either bring them to us or burn them in the fire.”

One of the greatest crimes instigated by a Church official was the destruction of the Serapeum in 392 CE. The Serapeum was built by Ptolemy III in the third century BCE and was dedicated to Serapis, a Greco-Egyptian deity combining Osiris and Apis. It was said to be one of the largest and most magnificent temples of the ancient world. It housed thousands of scrolls belonging to an offshoot collection of the Great Library of Alexandria, which became all that remained of the library after its destruction. In the center of the temple was a grand statue of Serapis overlaid with ivory and gold. The pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that the temple’s splendor was such that “mere words can only do it an injustice.”

Accounts of the events surrounding the Serapeum’s destruction differ, but it is thought to have begun when Theophilus, bishop of Alexandria, and his followers mockingly paraded pagan artifacts in public, provoking pagan attacks. The Christians counter-attacked, and the pagans took refuge in the Serapeum. Emperor Theodosius, who had passed a decree closing all pagan temples and forbidding pagan worship in 391, sent a letter to Theophilus granting pardons to the pagans and instructing him to destroy the temple.

The destruction of the Serapeum was celebrated by Christian chroniclers. “And that was the end of the vain superstition and ancient error of Serapis,” one concluded. Serapis was described as a “decrepit dotard.”

Christians are thought to have destroyed about two and a half thousand shrines, temples, and religious sites throughout Alexandria (a footnote explains that this figure derives from a fourth-century register of the city’s five districts). One Greek professor wrote, “The dead used to leave the city alive behind them, but we living now carry the city to her grave.”

About twenty years later, in 415 CE, the renowned philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer Hypatia of Alexandria was murdered by a Christian mob. This was the culmination of a chain of events arising from the clash between Orestes, Imperial Prefect of Alexandria, and Cyril, archbishop of Alexandria, over the city’s large Jewish population. Hypatia was a friend of Orestes, and Christians targeted her as a scapegoat for Orestes’ unwillingness to negotiate with Cyril. One day in March, she was attacked by a mob of Christians who dragged her to a nearby church, stripped her naked, and stabbed her with shards of pottery. Her body was dismembered and burned.

It is true that the conflict that led to Hypatia’s death was ultimately a political one and that her murder was not a spontaneous attack motivated solely by Christian hatred of paganism. But Hypatia’s murder shows that, regardless of their precise motivations, Christians had no qualms about brutally murdering one of Alexandria’s greatest thinkers. Hypatia’s death was even celebrated by later Christian chroniclers such as John of Nikiu, who equated her learning with “satanic wiles” and praised Cyril for eradicating idolatry in Alexandria.

Nixey does downplay the fact that both parties engaged in violence over the course of these events. Then again, her stated intent was to document Christian violence alone, and thus she cannot be faulted for her bias. Moreover, while it is true that pagan mobs committed sporadic acts of violence against Christians, these cannot justly be compared to Christian violence. The latter involved the destruction of cultural heritage (statues, shrines, temples, libraries), whereas the former arose as a response to the civilizational threat that Christianity represented.

The destruction of paganism also took place within monastery walls. Monks would write over the texts of Classical manuscripts with ecclesiastical literature, erasing them by scrubbing their surfaces with pumice stones. Cicero’s De re publica was written over by Augustine. A biography by Seneca was written over with the Old Testament. Archimedes’ Method of Mechanical Theorems was overwritten with a prayer book. It was only recently, with the aid of modern imaging technologies, that scholars were able to recover the Archimedes Palimpsest in its entirety.

Basil of Caesarea’s influential “Address to Young Men on Greek Literature” undoubtedly had an impact on which texts were preserved and which were not. In the essay, Basil (St. Basil “the Great”) outlined which works of Classical literature were acceptable in his eyes. He advised Christians to shun the bawdier and more violent works of Classical literature, as well as those works in which Greco-Roman deities were overtly praised. Many works were simply excised from the canon as a result. As for works of philosophy, monks had little interest in copying out the writings of philosophers who opposed Christianity, except with the express purpose of refuting them (as Origen did in his Contra Celsum).

The decline of Classical literature was thus “slow but devastating.” It is estimated that less than ten percent of Classical literature has survived into the modern era. In terms of Latin literature specifically, it is estimated than only one percent has survived. Interest in Classical authors reached a low point during the first few centuries of the Early Middle Ages, not to be revived until the late eighth century. Nixey writes:

From the entirety of the sixth century only ‘scraps’ of two manuscripts by the satirical Roman poet Juvenal survive and mere ‘remnants’ of two others, one by the Elder and one by the Younger Pliny. From the next century there survives nothing save a single fragment of the poet Lucan. From the start of the next century: nothing at all.

The Catholic Church did assimilate elements of Classical philosophy. Neo-Platonism, for instance, influenced a number of Christian philosophers, from Augustine, Origen, and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite to later figures such as Marsilio Ficino and Ralph Cudworth. They represent Christianity at its best, i.e., its most Hellenized. But when one strips away the pagan veneer layered upon the Church and dives to the heart of Christian teachings (of which the early Christians are the best representatives), one finds that the general attitude toward Classical learning, and knowledge in general, is hostile. One writer railed against those who “put aside the sacred word of God and devote themselves to geometry . . . Some of them give all their energies to the study of Euclidean geometry, and treat Aristotle . . . with reverent awe; to some of them Galen is almost an object of worship.” This condemnation of worldly knowledge was common among early Christians. It is embedded in the Bible, beginning with Adam and Eve and the story of the Tower of Babel. This theme persists throughout scripture. Paul writes in his first letter to the Corinthians that “the wisdom of this world is foolishness with God” (1 Corinthians 3:19). Another passage in this letter is particularly illustrative of the Christian disregard for knowledge as well as of the slave morality inherent in Christianity:

. . . God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty; and base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nought things that are. (1 Corinthians 1:27-28)

Celsus observed that “slaves, women and little children” and “the foolish, dishonorable and stupid” were those most receptive to the Christian message, which is not surprising in light of the Christians’ contempt for the wise, the strong, and the honorable.

Book-burnings were not uncommon. The works of the Neo-Platonic philosopher Porphyry, for example, were burned on the orders of Constantine; about a century later, Theodosius II and Valentinian III also consigned his works to the flames. Ammianus Marcellinus writes that:

. . . innumerable books and whole heaps of documents, which had been routed out from various houses, were piled up and burnt under the eyes of the judges. They were treated as forbidden texts to allay the indignation caused by the executions, though most of them were treatises on various liberal arts and jurisprudence.

Indeed, although Christians ostensibly only burnt books pertaining to magic, divination, and Christian heresy, works of philosophy were sometimes lumped under this category. Dirk Rohmann writes:

Moreover, while there have been ancient precedents to suggest that certain philosophers were characterised as magicians, in Late Antiquity magic and heresy came to be linked more clearly to these philosophical traditions. . . . Heretics were thus not only understood as non-conformist Christians, but occasionally those pagans whose opinions informed Christian-heretical discourse could also be dubbed as heretics in Late Antiquity, as opposed to the modern understanding of the term heresy that is limited to Christians. Along with imperial and ecclesiastical legislation that outlawed magical, heretical and astrological texts, I have argued that within Christian communities an unwillingness arose not only to preserve texts on these subjects but also texts that were related to these genres or were considered the basis for astrological or heretical world-views.[1]

A common belief among early Christians was that pagan works of art, literature, philosophy, and so on were demonic. They believed in the literal existence of demons, winged minions of Satan who enticed humans to commit sins. Pagan temples were thought to be centers of demonic activity. According to Augustine, “All the pagans were under the power of demons. Temples were built to demons, altars were set up to demons, priests ordained for the service of demons, sacrifices offered to demons, and ecstatic ravers were brought in as prophets for demons.”

This gave rise to great paranoia. Christians fretted over whether using the same baths as pagans, for example, would infect them with demons. One Christian wrote to Augustine asking him whether it would be all right for Christians to eat food found in a pagan temple in the event that they were starving and there was no other option. (Augustine replied that it would be better to die from starvation.) Paganism was described as if it were a disease. It was natural, then, that Christians would want to eradicate it.

Christians believed that pagan statues were possessed by demons and could only be purged of demonic influence if they were damaged in some form (at a minimum, by chopping off the nose or limbs). Dragging them, spitting at them, or throwing dirt at them was thought to be insufficient. The Christian mutilation of ancient statues can be seen in museums today. Nixey writes:

In Athens, a larger-than-life statue of Aphrodite has been disfigured by a crude cross carved on her brow; her eyes have been defaced and her nose is missing. In Cyrene, the eyes have been gouged out of a life-sized bust in a sanctuary of Demeter, and the nose removed; in Tuscany a slender statue of Bacchus has been decapitated. . . . A beautiful statue of Apollo from Salamis has been castrated and then struck, hard, in the face, shearing off the god’s nose. Across his neck are scars indicating that Christians attempted to decapitate him but failed.

It is also likely that some of the damage suffered by the Parthenon, particularly the East pediment (which depicts the birth of Athena), can be attributed to Christians. Images of gods at the Dendera Temple complex also show signs of having been attacked with blunt weapons.

The belief held by most Christians that paganism was demonic and diseased prevented them from peaceably tolerating their pagan neighbors. Constantine’s famous Edict of Milan, passed in 313 CE, nominally established religious freedom throughout the Empire, but persecution of pagans began soon after the edict was passed. Constantine’s biographer praised him for having “confuted the superstitious error of the heathen in all sorts of ways.” Indeed, during the latter half of his reign, Constantine himself ordered the pillaging and destruction of pagan temples, such as the temple of Asclepius in Cilicia and a temple of Aphrodite in Lebanon. He also ordered the execution of pagan priests. Statues were forcibly removed from temples and melted down, contributing to the growing wealth of the Church. Others were stolen and kept in the homes of wealthy Christians. The poet Palladas remarked of these that “here, at least, they will escape the cauldron that melts them down for petty change.”

Constantine’s son banned pagan sacrifices in 341, declaring that “superstition shall cease.” In 356, the worship of pagan images became a capital crime. He also ordered the closure of temples. Following the brief reign of Julian “the Apostate” (361-363), Rome was ruled by Christian emperors until the end. Julian was succeeded by Jovian, who ordered the destruction of the Royal Library of Antioch and reinstated the death penalty for those who worshiped pagan gods. Nicene Christianity was declared the official religion of the Empire in 380, during the reign of Theodosius I. From 389 to 392, Theodosius issued a series of decrees banning pagan sacrifices and other rituals, closing pagan temples, and abolishing pagan holidays. He declared,”No person shall be granted the right to perform sacrifices; no person shall go around the temples; no person shall revere the shrines.” He also disbanded the Vestal Virgins and the Olympic Games. In 399, he passed a decree authorizing temple destruction, announcing that “if there should be any temples in the country districts, they shall be torn down without disturbance or tumult. For when they are torn down and removed, the material basis for all superstition will be destroyed.”

The incident of the removal of the Altar of Victory in 382 is illustrative of the one-sidedness of the “tolerance” ostensibly accorded to all subjects of the Empire. Christians objected to the presence of the Altar of Victory in the Roman Senate House, and the Christian emperor Gratian had it removed. The senator Symmachus petitioned Valentinian II, requesting the restoration of the Altar and making an appeal to religious tolerance, but he was rebuffed.

In 399, Theodosius’ son Arcadius decreed that all remaining pagan temples should be demolished. In 408, his brother and co-emperor Honorius issued a decree proclaiming that “if any images stand even now in the temples and shrines, they shall be torn from their foundations . . . The buildings themselves of the temples which are situated in cities or towns or outside the towns shall be vindicated to public use. Altars shall be destroyed in all places.”

Nixey emphasizes that these were not hollow decrees. Christian records themselves attest to this. Marcellus, Bishop of Apamea, was described as “the first of the bishops to put the edict in force and destroy the shrines in the city committed to his care.” (He was later burnt alive by pagans in retaliation.) One Christian writer rejoiced that emperors would “spit in the faces of dead idols, trample on the lawless rites of demons, and laugh at the old lies.” Another gloated, “Your statues, your busts, the instruments of your cult have all been overturned – they lie on the ground and everyone laughs at your deceptions.”

It is estimated that in 312, about seven to ten percent of the Roman Empire was Christian (four to six million out of a population of about sixty million). Within a century, the reverse had come to pass, and between seventy and ninety percent of the Empire was Christian. Most conversions took place out of intimidation and were prompted by the destruction of temples and sacred objects. Libanius, who was banished from the Empire in 346, remarked at the end of the fourth century that temples were “in ruins, their ritual banned, their altars overturned, their sacrifices suppressed, their priests sent packing and their property divided up between a crew of rascals.”

Where the Christian destruction of Classical heritage is usually downplayed or overlooked, stories of Christian martyrs in late Antiquity have become ingrained in the popular imagination. Martyrs were venerated by the Church, and their stories were told and retold, often exaggerated and taken out of context. Thus there are some lingering misconceptions surrounding Christian martyrdom in ancient Rome.

The idea that Christians were tortured and executed en masse by a continuous succession of bloodthirsty Roman emperors is false. During the first two and a half centuries following the birth of Christ, the only instance of Imperial persecution of Christians was Nero’s brief persecution of them in 64. Over the course of three centuries of Roman rule, there were fewer than fifteen years of government-led persecution of Christians. Importantly, as Nixey notes, the Romans did not attempt to eradicate Christianity itself. If Rome had directed the full weight of its Imperial might toward halting the spread of Christianity in its earliest days, it would have succeeded.

After Nero, the Imperial persecution of Christians did not recommence until nearly two centuries later, during the reign of Decius. The Decian persecution began in 250 CE, after Decius decreed that all Romans had to perform sacrifices to him and to the Roman gods. His edict did not target Christians specifically; his intent was to unify the Empire and ensure loyalty from his subjects. Failure to adhere to the edict was punishable by death, but Christians were given the opportunity to apostatize. The edict lasted only one year. This was soon followed by the Valerian persecution, which was similar in effect and lasted from 257 to 260.

The most severe imperial persecution of Christians was the “Great Persecution” under Emperor Diocletian, which lasted from 303 to 313. Hundreds of Christians were killed, tortured, or imprisoned. However, the majority of Christians in the Empire were able to escape punishment, whether through apostasy, bribery, or fleeing the Empire. Diocletian’s efforts overall were ineffectual.

Nixey devotes a chapter to analyzing the correspondence between Pliny the Younger, governor of Bithynia, and Emperor Trajan on the subject of Christians in the Empire. In 112 CE, Pliny wrote Trajan asking for counsel on how to deal with local Christians, who were disrupting the peace. This letter (Epistulae X.96) is the first recorded mention of Christians by a Roman writer and provides much insight into how early Christians were perceived by the Romans. Pliny saw them as an irksome cult that undermined Imperial unity and provoked disorder. His “persecution” of Christians was born not out of fanatical hatred, but out of pragmatism. He did not object to them on religious grounds and never refers to them as being wicked, possessed by demons, and so on. Trajan’s response to Pliny states that Christians ought to be punished. But he adds one important clause: “These people must not be hunted out” (conquierendi non sunt).

Pliny thus saw execution as a last resort. He gave recalcitrant Christians multiple opportunities to comply with the law. Other Roman officials did the same. There is one account of a young Christian girl who voluntarily presented herself to the Roman governor Dacian in the hopes of being martyred. He did not want to kill her and implored her to comply: “Think of the great joys you are cutting off . . . The family you are bereaving follows you with tears.”

The glorification of martyrdom meant that many Christians were enthusiastic about being martyred. When the late-second century governor Arrius Antoninus executed some Christians in his province, local Christians flocked to him and demanded to be killed in a similar manner. This prompted him to remark, “Oh, you ghastly people. If you want to die you have cliffs to jump off and nooses to hang yourselves with.”

It says something about Christianity that its greatest heroes are not those who achieved great things but rather those who were made to suffer. It brings to mind Julius Evola’s description of Christian asceticism as “a kind of masochism, of taste for suffering not entirely unmixed with an ill-concealed resentment against all forms of health, strength, wisdom, and virility.”[2] It also attests to the inherent egalitarianism of Christianity; George Bernard Shaw once defined martyrdom as “the only way in which a man can become famous without ability.”

The life-negating nature of Christianity was also manifested in the Christian attitude toward everyday Roman pastimes. Christians were repelled by the Romans’ frank attitude toward sexuality and sought to suppress erotic art and literature. They denounced feasts of merriment, and a decree forbidding “convivial banquets in honor of sacrilegious rites” was passed in 407. Wrestling was labeled “the Devil’s trade.” Christians also railed against bathhouses, which functioned as town squares and were thought to be infested with demons. Statues of Roman deities that stood in bathhouses were often destroyed.

It is ironic that in their quest to divorce themselves from the material world, early Christian monks became obsessed with earthly sins to a pathological extent. Monks spent their days contemplating their sins and reproaching themselves. Early Christian descriptions of demons and the sins they incite are meticulous and extensive. Accounts of martyrdom often linger over the gruesome procedures by which Christians were supposedly killed and evince an almost masochistic preoccupation with torture.

Nixey is right to point out that the Romans did not celebrate abject licentiousness and debauchery, as is sometimes assumed. The Romans prized modesty (pudicitia or pudor) and self-discipline (gravitas). There were legal restrictions on sexuality, and hypersexuality was looked down on, as was effeminacy. Unlike Christians, though, the Romans embraced sexuality as a natural part of life and did not seek to smother it.

Nixey fails to make a similar clarification on the issue of religious tolerance. Her description of Roman civilization as “fundamentally liberal” in this regard is misleading. Romans were tolerant of others insofar as they made offerings to Roman gods and to the Emperor; the Empire enforced orthopraxy rather than orthodoxy. Hence, educated Roman elites, despite the fact that many were unbelievers, still made offerings to the gods and adhered to traditional Roman customs (mos maiorum).

Roman polytheism was pluralistic in the sense that a man could worship, say, both Jupiter and Isis or Mithras. Imported cults from Egypt and the East were introduced to Rome in the first century and gradually became a part of Roman religion (though they never acquired the status of traditional Roman deities). However, the government did place restrictions on cults that were perceived as a threat to Imperial unity. In 186 BCE, for example, the Senate prohibited the Bacchanalia (a mystery cult with roots in the Dionysian Mysteries) on the grounds that the cult’s secrecy could breed conspiracy and political subversion.

Of course, the purpose of the ban on the Bacchanalia was not to eradicate the cult, but to regulate it and ensure the supremacy of Roman religion. The ban merely placed initiates under the watch of consuls and stipulated that Bacchanalian rites required the approval of the Senate in order to be performed. This is a far cry from the Christian attitude toward pagans, which was one of unhinged hostility bent on the total eradication of paganism. Herein lies one of the essential differences between paganism and biblical monotheism.

Indeed, the extermination of paganism was celebrated by Christians. Isidore of Pelusium triumphantly declared in the early fifth century that “the pagan faith . . . [had] vanished from the earth.”[3] In 423, Theodosius decreed that “the regulations of constitutions formerly promulgated shall suppress all pagans, although we now believe that there are none [emphasis mine].”[4] By the time of Hypatia’s murder in 415, Classical paganism was in its death throes.

By the time Justinian ascended to the throne in 527, the destruction of paganism had more or less already taken place. Pagans were still around, but the greatest damage had already been done. Nixey overdramatizes Justinian’s closing of the Neo-Platonic Academy in 529, which was largely a question of ceasing to publicly fund the institution (she writes this off as “a finicky detail or two about pay”). The Ne-Platonic Academy could not boast a “golden chain” going back to Plato, as it possessed no direct links to the original Platonic Academy (which was destroyed when Sulla sacked Athens in 86 BCE). The closure of the Academy did not plunge Europe into the Dark Ages, as she claims. The “seven last philosophers” indeed fled Athens and sought refuge in the court of the Persian emperor Khosrow I, but they returned to Athens shortly thereafter. Upon their return, Justinian granted them residence in the Empire and permitted them to practice philosophy and teach privately. The teaching of philosophy in Athens continued for about fifty years, until Athens was sacked by the Slavs in 582.[5] This is not to say that Justinian was innocent; he prohibited paganism, executed pagans, and staged book-burnings throughout the Empire.

Nixey’s implication is that the Dark Ages spanned the entirety of the Middle Ages. She does not elaborate on this, but one of her main influences is Edward Gibbon, whose view of the Middle Ages was notoriously dim. More recent medieval scholarship has called this trope into question. The first few centuries of the Early Middle Ages were characterized by cultural and economic decline, but the Middle Ages as a whole witnessed many great achievements. Three cultural renaissances occurred during the Middle Ages: the Carolingian Renaissance in the eighth and ninth centuries, the Ottonian Renaissance in the tenth century, and the Renaissance of the twelfth century. These periods saw a renewed interest in Greek and Roman philosophy, literature, science, and so on. Of course, the achievements that took place during the Middle Ages owe nothing to Christianity and everything to Europeans themselves. It is in spite of Christianity, and not because of it, that the medieval renaissances took place. It is in spite of Christianity that European civilization in general was able to attain such great heights.

There are a handful of sloppy errors throughout the book. For instance, Nixey’s assertion that the centuries after Constantine did not produce any satirical poets is false; there were some. They were generally unenthusiastic about Christianity. The final elegy by the sixth-century poet Maximianus, thought to be the last true Roman poet, discusses his impending death and has been interpreted as a lament on the decline of the pagan world.

Then there are some deeper flaws, in addition to those already mentioned. She projects eighteenth-century Enlightenment ideals onto Greco-Roman civilization, as suits her New Atheist fable. She overlooks the fact that philosophy and mysticism were not mutually exclusive in the ancient world. The boundary between philosophy and theurgy, mysticism, and magic was a blurry one; as mentioned earlier, condemning texts on magic and divination to the fire led to the burning of works of philosophy as well. Skepticism was also confined to the elites; most ordinary Greeks and Romans themselves did believe in the gods and supernatural forces.

She does not mention that the Roman aristocracy was in a state of decline, as this would undermine her praise of their atheism and cosmopolitanism. By the time of Constantine, the aristocracy had lost its martial spirit and had become soft and complacent. Ammianus Marcellinus bemoaned the fact that “the few houses that were formerly famed for devotion to serious pursuits now teem with the sports of sluggish indolence.”[6] This made it easier for Christianity to infiltrate the elite. As the elite became more Christianized, many converted to Christianity out of a desire for upward mobility.

Another flaw that stands out is the curious omission of a certain tribe. Nixey does not mention Jews outside the context of Hypatia’s murder other than to describe them as “the hated enemies of the Church,” citing John Chrysostom’s anti-Jewish homilies. But the Jews both directly and indirectly contributed to the destruction of the Classical world. The fanatical hatred and dogmatism of the early Christians was directly inherited from their Jewish forebears. Exodus 22:20 reads, “He that sacrificeth unto any god, save unto the LORD only, he shall be utterly destroyed.” Jews also engaged in the destruction of pagan statues, temples, and works of art themselves. During the Kitos War, for example, Jewish rebels led by Lukuas ravaged Cyrenaica, destroying pagan statues and temples as well as Roman official buildings and bathhouses. Additionally, they ethnically cleansed the region by brutally murdering as many as two hundred forty thousand of its inhabitants.[7] The carnage was such that Rome had to restore the population by establishing new colonies there. Lukuas and the Jews then set fire to Alexandria, destroying Egyptian temples and desecrating the tomb of Pompey. This was but one of several Jewish rebellions against the Roman Empire.

The parallels between the Jewish and Christian crimes against pagans are striking. Roman authorities correctly recognized Christianity as a form of Judaism in disguise. The destruction of statues and the like was not unheard of in the ancient world, but it usually occurred in the context of Imperial conquest and regime change. The Jewish and Christian crimes against pagans, on the other hand, stemmed solely from the hatred and vengeance intrinsic to biblical monotheism. Both Jews and Christians claimed a monopoly on religious truth and declared that all “false” religions must be eradicated. Contrast this Semitic intolerance with Celsus’ assertion that “there is an ancient doctrine [ἀρχαῖος λόγος] which has existed from the beginning, which has always been maintained by the wisest nations and cities and wise men.”[8] (Celsus goes on to exclude the Jews from the “wisest nations” and describes Judaism as a perversion of ancient wisdom.)

Both the Jewish and Christian attacks on Indo-European paganism were essentially ressentiment-fueled slave revolts. In a very literal sense: Jews in the Roman Empire actually did descend from slaves imported from the East, and Christianity’s earliest and most zealous converts were likewise drawn from the lowest rungs of society. Christianity appealed to slaves because, like Judaism, it prized all that represented the opposite of their superior masters. Nietzsche noted this parallel, remarking that Christianity stood “all valuations on their head” and that Judaism represented an “inversion of values.”[9] [10] Jan Assmann has used the term “normative inversion” to describe the process whereby elements of Judaism evolved as a conscious rebellion against Egyptian religion.[11] The term could easily be applied to Christianity as well.

It is possible that Nixey decided to downplay Christianity’s Jewish roots in order to avoid potential accusations of anti-Semitism. If this is the case, it is a testament to the fact that, two thousand years after the Jewish-Roman Wars, Jewish subversion is still a very real phenomenon.

A Christian may retort that the actions of zealous monks two millennia ago have little bearing on Christianity today and as it evolved in Europe. However, one cannot truly understand Christianity – and thus the core that lies buried behind the magnificent edifice of the Catholic Church – without studying its early history and scripture. No amount of pagan influence can fully suppress the poison that lies at the heart of Christianity, which exists fundamentally at war with Indo-European paganism as well as with Europe itself.

I cannot recommend The Darkening Age without reservations, but it is nonetheless a compelling and powerfully-written account of the Christian destruction of Classical Antiquity. The errors scattered throughout are unfortunate, and one hopes that someday another Anglophone writer will come along and write a better popular work on the subject. But in the meantime, this book provides a solid counterweight to widespread misconceptions about early Christian history. It ably demolishes the myths which hold that Christianity triumphed solely through peaceful means, that early Christians were innocents who were barbarically slaughtered by evil Roman emperors, and that Christianity preserved more than it destroyed. None of the book’s flaws are so grave as to diminish the truth of its thesis. It serves as a potent reminder of the threat that biblical monotheism has posed and continues to pose to European civilization.

Notes

[1] Dirk Rohmann, Christianity, Book-Burning, and Censorship in Late Antiquity: Studies in Text Transmission (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016), p. 148.

[2] Julius Evola, The Doctrine of Awakening: The Attainment of Self-Mastery According to the Earliest Buddhist Texts (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions International, 1996), p. 74.

[3] Peter Brown, Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), p. 128.

[4] Ibid., p. 128.

[5] Alan Cameron, “The Last Days of the Academy of Athens,” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society, vol. 195 (1969), pp. 8, 25.

[6] Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae XIV.6.18.

[7] Dio Cassius, Hist. rom. 5.68.32.

[8] Origen, Contra Celsum 1.14.

[9] Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Judith Norman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), p. 56 (§62).

[10] Ibid., p. 84 (§195).

[11] Jan Assmann, Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 31. Greg Johnson wrote an excellent series of articles on this book.

The%20Christian%20Destruction%20of%20the%20Classical%20World

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

The Worst Week Yet: April 21-27, 2024

-

The Significant and Decisive Influence that Leads to Wars

-

Get to Know Your Friendly Neighborhood Habsburg

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

30 comments

An important book, even with its flaws. Its flaws can be blamed on author political/philosophical leanings, as well as that of her perceived audience. Even with that, her text will be of immense use to us of the Right. Parallels to the practices of Muslims and the Far Left are obvious and stRiki-Eiking.

Abrahamic traditions were always the greatest enemy of World Religion, and an enemy of mankind. Efforts like this book are to be celebrated whether they come from the Right or the Left. Christianity is to be fought against, tooth and claw, if our tradition is to be preserved.

Bloody great book, I am pleasantly surprised to see a positive review of it here. Quite a few writers from the contemporary Right wrote of the damage early Christianity did from the Aryan point of view, but it is nice to have a “mainstream” book that focuses solely on this subject.

Yeah, Nixey’s fedora-atheist vision of Pagans and hence the reasons for her sympathy for them are far removed from our own, but that ought not deter anyone from reading the book. It doesn’t change the facts presented in it, nor their value to us.

‘It is in spite of Christianity that European civilization in general was able to attain such great heights.’

Eh careful,

One of the reasons Rome declined is that it was dependent upon expansion. Once Rome stopped expanding and conquering wealth it suffered economically (see the Roman invasion of Gual). Because only so much expansion was possible (Rome never had a great navy being mediterranian based-they could not conquer China because of that) they could not stop their wealth going to China. It was a constant complaint that specie was leaving Rome and going east-one of the reasons why Rome was eventually abandoned and the capital of Byzantium was made Constantinople so that they could be better situated to control this outflow of capital. Along with Roman culture massively sanctioning usury (something the Catholic church banned for a long time btw) which reduced the Roman middle class to serfs (Rome was dependent upon its citizen soldiers) this was the main reason for Rome’s decline. Theories about a transformation in values etcetera are a long way behing these two reasons. Indeed the Islamic world which took more from Greco-Roman paganism than you might think (concubinage and an economy based not on work but on pillage and expansion) has declined massively since about 1700 when Europeans became strong enough to not just repel their attacks but to place them in check. Lacking the ability to expand (a la Rome) they have gone in to decline massively (think what Saudi Arabia, Algeria etc would look like without White people pumping thier oil). Also one of the main reasons for the so called ‘dark ages’ was not Christian iconoclasm and intolerance, but the invasion of the classical world by Arab savages. The resulting downturn lasted a couple of centuries but was pretty much over by about 900.

The foundation of the modern western world is the honour of labour- a concept foreign to paganism. Christian monks preserved civilisation when Europe was cut off from the classical world which the Arabs were already composting. Once new trade routes circumvented the middle east the Arabs were quickly superseeded. Centuries of outbreeding (again directly connected to Christianity) has made the formation of stable large polities possible. Rome never put its surplus capital into industrialisation wheras the Christian middle ages did (monasteries were powerhouses of agricultural development and some of the first factories were in Christian institutions).

Desire the return of paganism? Be careful what you wish for.

Christian out breeding is today called inter racial marriage, a step up from the inter tribal marriage of old.

Why are you angry or upset then?

Go give your children in marriage to Africans & embrace the increased love between mankind that comes from far flung social ties.

Christ cuck

This is a rather simplistic account. But if we grant its argument and continue with this line of reasoning, we must conclude that it was good that Christianity destroyed the classical world before the classical world could destroy the white race.

Christianity was able to do both.

A delicious piece that both informs and angers, and makes one slightly less outraged about the treatment of Christianity in the Soviet Union. What goes around…

I have been feeling myself drift over to the Christian side of things in recent years, but I find myself willing yet unable to subscribe to its philosophy. There is a great sadness in the loss of the old Pagan European traditions as it means there is little that remains to replace Christianity with, as was obviously the Christian intent. Christianity alone remains as the sole spiritual force in the West – as pagan sources are unverifiable, destroyed, defaced, rewritten and subject to reinvention by modern wannabe-pagans. The true nature of the maby ancient European faiths is lost to time, and that is an atrocity.

Looking forward, we either make our peace with Christianity, reject it totally and either live godlessly or start the impossibly herculean task of creating a new European spirituality out of nothing, or we retool Christianity to fit the proud Aryan folk traditions. The latter seems preferable to me.

Actually, quite a bit is known of Indo-European paganism, it’s not so quixotic. But the real task is to reinstill classical, “pagan” virtues and ways of viewing the world and our relationship with the divine, imo. Much of this was present in the middle ages despite European’s being nominally “Christian.”

You don’t need a committee of white people sitting around a table saying, “OK! Next on the agenda – creating a new religion for us.” This didn’t happen with old European paganism. It just developed from the ground up out of our biology.

“A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within.”- Will Durant

Very interesting. I’ll definitely be buying this one.

Maybe this is a little off topic, but today I listened to a talk by the historian Philip Jenkins on the incredible shift of Christianity from Europe to Africa(in demographic terms) which will be complete by 2025. Not only is this “shift in the center of gravity” of Christendom breathtaking in it’s scope and pace, but also in it’s character.

African Christianity is primarily focused on the message of social equality present in the New Testament as well as faith healing and protection from witchcraft and demons and ancestral spirits and curses. The cult of the Saints is also alive and well, even for “Protestants.” Also present are fanatical militias who exemplify crusader like zeal in their fights against Muslims.

There are an astonishingly large number of African Christian hymns being written today. Indeed it is a golden age of African Christian hymns, and they attest to the unique character of African Christianity. Also fascinating is the desire of African churches to expand into Europe. Some of the largest mega churches in Europe today are run by Nigerians and Congolese.

If any sort of socially conservative form of Christianity is to make a comeback in Europe, Jenkins says, it may be due to mass immigration from Africa. African’s take the scriptures VERY literally and they are very interested in undertaking missionary work in Europe, spreading the good news.

Fantastic article.

There have been many attempts to unite Christians and Pagans on the right, but anyone with knowledge of early Christianity knows that this is a fool’s errand. You cannot break bread with those who seek to destroy you and believe you are justly bound for eternal damnation. Christians will only ever tolerate Pagans so long as they don’t see us as a legitimate threat.

Christianity main appeal in the modern West is its ability to present itself as the only available alternative to the emptiness of atheism, hence the constant attempts to write off pagans as “larpers”. As the current wave of atheism inevitably collapses under its own shallowness and nihilism, a resurgence of traditional spirituality will arise among those already disillusioned with Abrahamic dogmatism and its “secular” mirror Marxism, facilitated by weakened Christian institutions and the connective power of the internet.

However, this will likely take decades to fully mature and be viciously fought against by neoliberals, Marxists and Christians using every tool at their disposal, so only time can tell if the Pagan will be able to rise to the challenge.

It sounds like many of the points Spandrell made in his “Bioleninism” essays would also apply to the early Christians. Namely that it’s easy to mobilize a mass movement of mediocrities by offering them status they can’t get any other way. Competent people are less inclined to revolution, as they tend to do well under any halfway sane social system.

The old solution was to crush the rebels without mercy and crucify any taken alive, but from about 100BC onward, Rome’s ruling class had such low fertility that it was genetically replaced every 100 years or so, and that seriously affected its cohesion and competence.

Cesar Tort’s work is very relevant here, he has been translating ‘Christianity’s Criminal History’ this year–

https://chechar.wordpress.com/category/kriminalgeschichte-des-christentums-books/

I don’t have a subscription to The Times but I managed to glean this on the free page.

It’s not exactly Tinder territory. But that is the question that was facing my father – the monk– as, one rainy day in 1974, he drove back from west Wales in a battered white Cortina next to my mother. The former nun.

My impression is that an article on the authoress would be more interesting than the book just reviewed here.

“The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom” by Candida Moss is also an excellent read for anyone from anti-Christian Right. Nixey actually mentions Moss’s excellent work in her book.

I saw this interesting excerpt from “Mein Kampf” that shows that even though Hitler was, for aesthetic and ideological reasons, angry at Christianity for having destroyed ancient paganism, he still could not help admiring, as a Machiavellian power politician, the efficiency such vast mental revolution was carried out with:

http://www.mondopolitico.com/library/meinkampf/v1c12.htm

“Movements which increase only by the so-called fusion of similar formations, thus owing their strength to compromises, are like hothouse plants. They shoot up, but they lack the strength to defy the centuries and withstand heavy storms.

The greatness of every mighty organization embodying an idea in this world lies in the religious fanaticism and intolerance with which, fanatically convinced of its own right, it intolerantly imposes its will against all others. If an idea in itself is sound and, thus armed, takes up a struggle on this earth, it is unconquerable and every persecution will only add to its inner strength.

The greatness of Christianity did not lie in attempted negotiations for compromise with any similar philosophical opinions in the ancient world, but in its inexorable fanaticism in preaching and fighting for its own doctrine.”

The Führer was a cynical worshipper of raw power, and thus no matter what his own aesthetic preferences might have been, he was practically forced to look down on ancient heathenism, that had allowed itself to be defeated by Christianity.

This would be the TRULY un-liberal approach to this issue – not mourning fo losers who allowed themselves be defeated. Vae victis!

Hitler even had that attitude towards Germanic heathenism:

https://books.google.fi/books?id=xeglDQAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&dq=chapoutot%20nazis&hl=fi&pg=PA73#v=onepage&q&f=false

“There being no doubt about the overwhelming cultural superiority of the Greco-Roman civilization, Hitler completely discounted the reactionary views of the SS, which attempted to resurrect Germanic cults, customs, and traditions, following Himmler’s lead. Not only were these cults and traditions culturally the equivalent of the Maoris’ gris-gris, but they had naturally disappeared over time because they were destined to perish: “It seems to me that nothing would be more foolish than to re-establish the worship of Wotan. Our old mythology had ceased to be viable when Christianity implanted itself. Nothing dies unless it is moribund . . . It’s not desirable that the whole of humanity should be stultified.”114”

Even the grim fatalism of ancient pagans themselves could agree with this approach – that like Kronos was once overthrown by his own son Zeus (after having himself once overthrown his own father Ouranos), the ancient pagan civilization fell because its predestined fate had arrived. No sentimental “happy ending,” but the moment of doom long anticipated, like with Oedipus.

Absolutely ridiculous. You are clearly ignorant of other references to Hitler’s views such as his Table Talks where he explicitly shows his love of the ancient world and his hatred of Christianity. It is clear that he wanted it gone from the minds of his people.

“not mourning fo losers who allowed themselves be defeated. Vae victis!”

How about this: A murderer comes into your house, rapes your wife and eats your children. By your very own logic you “allowed yourself to be defeated” and you cannot mourn because you and your kin were just losers.

There may some truth to that, but there simply is no way forward for us with Christianity and soon it will be an Africanized religion anyway.

Christianity has exhausted itself in the white world for reasons having to do with it’s fundamental nature of being intolerant and exclusivist and de-sacralizing. Christianity causes the desacralization of nature be insisting that God is a transcendent creator, standing above and outside his creation. This stands in stark contrast to Traditionalist religions that view God as immannet in nature. This eventually draws Christians to atheism when science contradicts anything in the revealed text– a weakness born also from it’s need for literalist readings of it’s texts. It simply has to be so that the bible is taken literally for it to work– and it must be without error.

Christianity paves the way for secularization and atheism when it insists on it’s own doctrine being true and all other religions false and in need of destroying because when an inevitable schism occurs(count all the heresies and religious wars and communal violence) within Christendom, peace can only be achieved with a secular state. when a nation is too divided on matters of religious interpretation it’s either splitting the nation up into separate states, genocide, forces conversion, or peace through secularization. With the peace of Westphalia, Europeans showed they simply had had enough of it.

The consequence is this takes the teeth out of Christianity and encourages more fragmentation of a religion which structurally requires absolute answers, infallibility, inerrancy, and consistency.

Remember too, that even before mass literacy and translation and printing of the bible for all to read and interpret for themselves, massive heresies caused huge unrest in major regions of Europe. Post printing press and with the arrival of mass literacy, it’s like trying to put the bones back into a fish. That said, I don’t know if this process was inevitable, but it was highly probable and has come to pass. So here we are.

You are cherry-picking his comments for those that suit your preferences. It is just as easy, if not easier, to make an opposite argument. I don’t blame you too much by the way, for there is an ongoing effort from some niche thinkers on the Right to present National Socialism as an inherently Christian project. I won’t name any names, but I am certain that most people here will instantly think of some of them.

As for the truly un-Liberal views, both Crowley and Evola rejected Christianity as being of any use for their projects, even tho in Crowley’s case he was ready to adopt trappings of any ideology that could be used as an outward package for Thelema. Any worth is far outweighed by the negatives that are intrinsic to it.

(and before you ask, I have about as much sympathy for the late Roman elite as I have for that of Weimar, ie none)

https://chechar.wordpress.com/2018/01/22/apocalypse-for-whites-xxxvii/

Posted by Cesar Tort, translated from Spanish by EVROPA SOBERANA

Goddamn, I miss Catholicism. The only problem with Catholicism is that it isn’t true. If anyone has an antidote to nihilism, please share.

The cure for nihilism is self-improvement, self-destruction and will to overcome. Modern society has accustomed us to instant gratification, stereotyped and “cookie-cutter” lifestyles that are meant to “comfort” the masses, not “fulfill” the great men.

I don’t remember the quote literally, but it went like “weak mean argue about their rights, strong men impose duties for themselves”. Life won’t be satisfying acquiring commodities, rights and pleasure; it will only be great when your effort bears fruits that you can completely claim for you, not in the material/economic level, but in the inner/honorific one.

That is a very good review. I know that I do not have to read the book, having read Gibbon’s Decline and Fall from cover to cover (and the parts up to the end of Justinian’s rule more than twice), many Church fathers, also Ammianus Marcellus, Zosimus, the man who wrote the bio. of Justinian and Theodora (forget the name, in latin alphabet, it has an initial P), all of the latter three were pagans, so the situation in the Eastern empire was very different from that in the Western empire, at least for a few centuries.

Never forget that most of the classical learning that was the basis of the Renaissance was mainly carried out of the eastern empire as it fell to the Moslem savages.

Constantinople had many precious pagan monuments until the Norman savages arrived there in the twelfth century, supposedly on their way to a crusade, but more intent on destruction and plunder. They set up a short-lived dynasty.

Of ancient literate societies, Europa has more extant ancient texts than any other place.

Despite the destruction, that is a point to note.

I suspect that the monks changed things at times, e.g. in Suetonius, the description of Nero, in Marcellus, the statement that a Chrirstian murderer was not responsible for the murder of Julian. However, the latter was clearly so frightened of and saddened by them in later in later parts of his account, perhaps he really did write it that way, but I doubt it. He idolized Julian, not in the religious sense.

I think that I have not said all that I intended, but tired and close to sleep.

So, on a lighter note, I really wish I could read Famous Whores of History by Suetonius, and his recipe book, as specific examples.

I have been thinking about that every now and then, how much of the surviving historical data was selected and tampered with by the Church… That train of thought is not without its pitfalls though, because you can end with this extreme scepticism where there is really no valid criterion for judging truth of any surviving records. But yes, few years ago I wouldn’t go there, but with all that I’ve learned in the meantime it hard to suppress certain doubts.

As for Procopius, he is not exactly trustworthy either beyond offering yet another confirmation that Justinian was indeed a Pagan. But such confirmation may be good enough (though, I share Gibbon’s less than enthusiastic view of the Eastern empire).

Now, now…

By what criteria can you take his claims about Justinian’s paganism to be true, whilst rejecting his claims about Justinian’s degeneracy and failure as a ruler to be false (for I suspect that this is what makes his claims “questionable” in your eyes)?

Your criterion would be would be alignment of his claims with your preferred historical narrative, and that would make you into Catherine Nixey.

I do not share your view of Procopius (and thank you very much for reminding me of the name), but have read the translations.

He was a very important historian. Maybe Theodora was a whore, maybe it is a slander. I think the truth is between the poles. The important thing is that that account has transcended so many years and come down to us. Very precious.

There is so much not translated from Byzantine Greek, if I was able to rewind my life, translating some would be a good life goal.

Rewinding is not possible, so the more modest goals of being proficient in the Greek and Russian scripts.

There is so much that has never been translated from Greek, I am sure that most is dull theology, but also would expect that a younger scholar would find it very rewarding as a speciality.

Which brings me back to the earlier point. Triumphant early Christians were terrible in many places, destroying many works, but we still have Homer, Plato, Socrates (OK, that only in a dubious form), so many more, and the many great latin writings

In China (really the only comparable cultural sphere in terms of letters at the time, maybe Persia, but wrecked by …), without the drive of a religious mania, masses of the old literature were repeatedly destroyed, simply for reasons of dynastic change, and there are far fewer genuine manuscripts (almost none, even copied) from those times in China.

Not to mention, several centuries later, the massive destruction by the mudslimes, everything in their so-called ‘golden age’ was from enslaved Christian and Persian scholars.

Not to say that I am at all a fan of Christian behaviour as they became dominant in the western Roman empire.

Reading Marcellinus on Julian almost makes me weep. I may be a Christian, but my sympathies are always with Julian.

That account, too, we only have thanks to monastic copyists.

So, unreliable as it may be at times, and as disappointing as knowing the titles but not being able to read e.g. much of Aristophanes, more was passed on than anywhere else.

See if this is a perfect fit for certain book (hint: it is):

“To separate legitimate history from pseudohistory, we need to alert ourselves to the characteristics that define one or the other.

We look, for example, for the evidence presented and where it comes from. We take note of the tone, attitude, and vocabulary used. When we suspect that sources are weak, absent, or manipulated, we check them out. The Internet swarms with websites of bad history but also gives us quick access to sound opinions and information from mainstream historians. We have the right and obligation to become suspicious of versions of history that lack nuance and context, appearing to cherry-pick bits of information to support established positions. As we have seen, sweeping historical generalizations and simplified black-and-white presentations of the past do not characterize the work of historians.

New Atheist historians relish issuing moral judgments about the past. They do not hesitate to condemn individuals, institutions, religions, and religion in general. Their absolutist pronouncements leave no room for further discussion or broader consideration of those condemned. They further confuse us by employing a loose vocabulary in which the meaning of words becomes muddled and unclear, beginning with the one most frequently invoked: religion.”

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment