Field of Dreams (1989)

Written and directed by Phil Alden Robinson

Starring Kevin Costner, Amy Madigan, James Earl Jones, & Ray Liotta

W. P. Kinsella

Shoeless Joe

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982

The most magical movie of 1989 was the baseball film Field of Dreams, which is based on the 1982 book Shoeless Joe by William Patrick “W. P.” Kinsella (1935-2016). The book is fictional, but it does incorporate some of Kinsella’s family history. For example, Ray’s father, John Kinsella, is described as having been born in North Dakota, which was likewise true of W. P.’s father. One could imagine the real John Kinsellla being a fan of “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and the Chicago White Sox as well, but this is unknown.

John Kinsella’s birthplace is out-of-place for the Kinsella clan, as they are old-stock Canadians. W. P. himself lived in Canada, and was born in Alberta. The movie says that Kinsella’s father served in the First World War, and the book describes him as having been gassed at the Battle of Passchendaele. The US Army was not at Passchendaele, however, although the Canadian army was. Many Canadians who write about events in the US tend to see American and Canadian events as intertwined when they often aren’t. It’s a reflection of the shared cultural heritage between Anglo-Canada and the US, despite their separate political orders.

W. P. Kinsella stated in an interview that “Ray” was named after a character in a J. D. Salinger short story, but the character of Ray in Shoeless Joe mirrors some of W. P.’s own thoughts and feelings in the 1980s. The film’s Ray Kinsella is a younger man than the author, and it is set in the present at the time the movie was made (1988). W. P. turned 53 that year, while Ray Kinsella (played by Kevin Costner) is 36. W. P. was not a Boomer; he was born in 1935. He saw the revolutions of the 1960s, but was too old to really be “with it.”

The 1980s farm crisis

Ray Kinsella in both the book and the movie is a farmer in Iowa. They both also show him as married to an Iowa girl named Annie (Amy Madigan) and with a daughter named Karen (Gaby Hoffmann). The book’s Ray went to Iowa to study and fell in love with the state, as well as an Iowa girl. Kinsella briefly tried to sell insurance, but then rented and later purchased a farm that ended up being barely profitable. His farm is mortgaged to Eddie Scissons, who claims to be the oldest living former Chicago Cubs player. Scissons is a major character in the book, but is left out of the movie. In both the book and the movie, Ray’s brother-in-law John is a landlord and investor who is trying to take the farm from Kinsella. John is played by Timothy Busfield in the film.

The film depicts the mortgage as a major part of the plot, which was a great artistic choice. The 1980s were an economic disaster for Iowa. High fuel costs, low agricultural prices, and high interest rates combined to create an economic storm that closed Midwestern tractor factories and shuttered banks. Many farmers went bankrupt.

The crisis was such that there were stories of farmers committing suicide so that their families would get the insurance money. There was even an urban legend that some farmers were taking out contracts on themselves with hired killers. This legend was woven into the 2015 film Dark Places. This farm crisis helped compel the family of Randy Weaver to move to Ruby Ridge, Idaho, leading to his infamous standoff with the feds. In the mid-1980s country music artists such as Willie Nelson held Farm Aid concerts, and the Reagan administration finally took action by adopting some price support polices.

The 1980s was a difficult time for Midwestern farmers. While Field of Dreams was being made, Iowa’s corn crop was failing.

To add insult to injury, nature itself struck a blow in 1988 in the form of an appalling drought. The only reason why Kevin Costner is shown walking in a field of tall corn stalks in the movie is that the filmmakers built a complex irrigation system to water the crops at the filming location. The drought is apparent in other parts of the film, however, where you can see large patches of brown and yellow grass in the fields in the background.

Large agribusinesses have moved into the Midwest, but rural living and small farm ownership could be revived if the telework revolution could be properly leveraged. In Field of Dreams it is remarkable to see how everyday technology has changed since the late 1980s. The film took place only a few years before the Internet became widely available, so the characters still have to go to libraries and press offices to do research by combing through old newspaper clippings and magazine articles.

In both the book and the movie, Ray Kinsella hears a voice that says, “If you build it, he will come.” By the end of the first page of the novel, Ray has built a baseball field. The film attempts to show realistically how an Iowa farmer would react to a mysterious voice in a cornfield telling him to build “it.” Ray then seeks advice from his wife and other Iowans about what the voice means. He eventually has a vision which shows him that he must build a field so that the ghost of “Shoeless” Joe Jackson (Ray Liotta) can return from across the veil and play baseball. The baseball field is like Valhalla, that place in Norse mythology where warriors feast and drink before fighting in battles for fun.

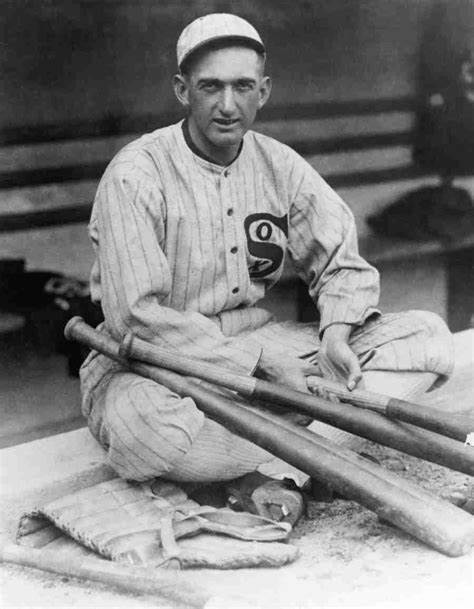

The ballfield is a financial burden to the Kinsellas in both the movie and the book. After considerable time passes, Shoeless Joe arrives, and soon there are ghostly baseball games centered upon the Chicago “Black” Sox — the eight players who were paid to throw the game at the 1919 World Series. Shoeless Joe was paid by the gamblers, but he played so well that many believe he was innocent of corruption. Shortly after the ghostly players arrive at Ray’s Iowa baseball diamond, the voice tells Ray to “ease his pain.”

In the book, Ray decides this means he needs to take J. D. Salinger to a baseball game to “ease” Salinger’s “pain.” Salinger (1919-2010), was a writer who wrote the classic novel about teen angst, The Catcher in the Rye. According to popular wisdom, it is a “banned” book, but this is in fact incorrect, as it can be found in every library. The “banned” moniker simply means that the Establishment wants you to read it. Indeed, many high school students were required to read it in their English classes.

The movie’s most important departure from the book is that, due to the threat of a lawsuit from the real-life Salinger, he is replaced by the entirely fictional author of a fictional book called The Boat Rocker named Terence Mann, who is played by James Earl Jones. Mann is said to be based on Salinger, but this character seems to be more similar to the radical sub-Saharan writer James Baldwin. While the book is excellent, the movie is magical, and it has themes that are important for getting on in real life.

Right-wing themes in Field of Dreams?

In the film there is a parent-teacher meeting which Annie Kinsella is keen to attend. An anti-Mann parent, played by Lee Garlington, encourages his book to be banned from the school. Annie objects to this, and Goodwin’s Law of Nazi Analogies is invoked alongside the “punch a Nazi” theme. At the meeting, Ray decides that he must take the reclusive Mann to a baseball game.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

This scene is notable in that it shows the state of mainstream liberal political thought a few decades ago. In 1988, ordinary liberals thought that they were the ones encouraging freedom of inquiry and expression. They weren’t, but they did at least posit free speech as an ideal in the late 1980s.

Ray takes his Volkswagen Bus to Boston. After finding Mann, Ray discovers that he has become disillusioned by the social changes brought about by the 1960s, as well as his part in those changes. Mann later says angrily that The Boat Rocker is not the reason why Ray stopped playing catch with his dad, and he didn’t appreciate the fact that people had said those sorts of things to him. The film critiques much of the cheap spiritualism of the 1960s as well as those aspects of the youth rebellion which were not productive, such as refusing to play catch with one’s father. There is also a fan theory which posits that Mann’s character is a ghost. You can read more about this theory here.

The social disruptions of the 1960s comprise two separate revolutions. The most critical social revolution of the early 1960s was “civil rights.” That revolution was carried out by Left-wing technocrats who knew how to wield power. They were not Boomers, as that generation was still too young. The second social revolution happened in the late 1960s and was carried out by people who were born after 1946, such as the fictional Ray Kinsella. Unlike the previous one, this revolution was not in fact Left-wing or technocratic. It in fact rejected the assumptions of the Leftist elite that had encouraged America to go to war in Vietnam, and unlike their less religious parents, many of the rebellious youth of the late 1960s later joined the Religious Right. Christian books sold in the millions by the late 1970s. There was also a subtle rejection of “civil rights.” It could be that the ferocious resistance they gave to the Lyndon Johnson administration was more related to his support for “civil rights” and sympathy for sub-Saharan rioting than a moral stand against the war in Vietnam.

That which is important versus that which is trivial

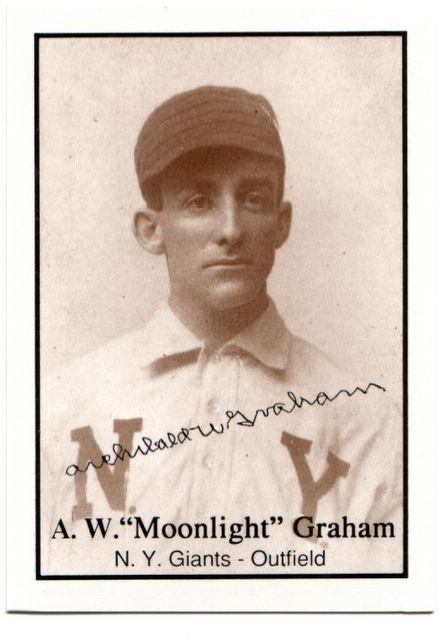

An important skill in life is to discern that which is truly important from that which is trivial. This is shown in the vision that Kinsella and Mann experience at the baseball game they attend together. Flashed upon the scene are the career baseball stats for Archibald Wright “Moonlight” Graham (Burt Lancaster in his final role), a rookie player who only got to play half of one inning as a right fielder for the New York Giants in 1905. The pair decide to follow the voice and “go the distance” to Chisolm, Minnesota in order to find Graham and bring him to Ray’s baseball field.

Kinsella and Mann discover that Graham has passed away. Ray decides to go for a walk while Mann calls his family after he is reported missing in the news. (In the movie, this scene can be interpreted as further proof that Mann is a ghost.) On the quiet streets of Chisolm, Ray meets Moonlight Graham after all, and they discuss baseball. It turns out that baseball isn’t all that important, however. Moonlight Graham’s short career in the majors was not as important as his work in Chisolm, as a doctor. Graham tells Ray, “Son, if I’d only gotten to be a doctor for five minutes . . . now, that would have been a tragedy.”

Dr. Archibald Wright “Moonlight” Graham (1876-1965). Field of Dreams depicts Ray meeting Moonlight Graham in 1972.

In both the film and the book, Moonlight Graham emerges from the baseball field and saves Karen Kinsella from choking on a hot dog. Shortly afterwards, tourists show up and pay Ray $20 per head to walk around the field and watch the game, thereby saving the farm. The clear message is that baseball isn’t as important as saving lives.

Being a rookie in any trade

Kinsella and Mann pick up the ghost of the young Moonlight Graham and drive him to Iowa to play ball. When I was in the military, an old solider once told me that one’s first shot “at bat” in any new job was not unlike that of Moonlight Graham’s first time at bat in Field of Dreams. Moonlight winks at the pitcher in an attempt to distract him, and in response the pitcher tries to hit Moonlight in the head with a fastball, twice. None of Moonlight’s teammates or the umpire seem to care.

A relative of mine was recently working a job away from home. He sent me a message explaining that he was getting some grief from the older people at his workplace, so I sent him a YouTube clip of Moonlight Graham’s first time at bat from Field of Dreams and explained that the older fellows were just testing his mettle. In all jobs, the first two (metaphorical) pitches coming your way will likely be aimed at your ear. Don’t give up, keep calm — and be prepared for a low-and-away pitch — metaphorically, of course.

Family is important

In the book, Shoeless Joe, Ray, and his father are not estranged, and Ray’s mother is still alive in Montana and living with Ray’s aunt. It is rather Ray’s twin brother who remains unreconciled with his father. When John Kinsella appears in the baseball field, the three men play catch, but the reconciliation is not nearly as emotional as that between Ray and his father in Field of Dreams. Indeed, in the film the reconciliation between Ray and his father is the main point of the story. In the late 1980s there was a cultural trend of stories about thirtysomething Boomers reconciling with their parents, or else reconciling the fact that they were becoming like their parents. In 1987 ABC produced a show called Thirtysomething starring Timothy Bushfield, which depicted the lives of Boomers as ordinary adults. And in 1988 the band Mike & the Mechanics released their greatest hit, “In the Living Years,” which encourages adults to reconcile with their elderly parents while they are still living.

In its youth, the Boomer generation adopted the ethos of “not trusting anyone over 30.” By the late 1980s it was clear to all that not trusting anyone over 30 was an unsustainable ethos.

The real magic of Field of Dreams

Many people who were in their early thirties in 1968, such as W. P. Kinsella himself, grasped the nature of the technocratic revolution of the early 1960s and mistakenly applied those same principles to the later revolution. This idea runs throughout both the movie and the book. President Nixon, a figure despised by1960s liberals, is referenced negatively twice in the film. The book also makes some negative remarks about Billy Graham, the televangelist who became a major figure in American culture after 1968. The second 1960s revolution didn’t end up going in a leftward direction, however. The youth of 1968 tolerated “civil rights,” but ended up moving to the suburbs as thirtysomething “yuppies” in the 1980s. They also supported Bill Clinton’s 1994 Crime Bill, which was aimed at putting young sub-Saharan men in prison to reduce crime.

A rejection of the ideology of “civil rights” can be found in Field of Dreams, although only subtly. Throughout most of the twentieth century, Major League Baseball was happily segregated by race, which allowed the white audience to genuinely sympathize with the white players. It also kept the Majors free of sub-Saharan social pathologies. All of the sports franchises of today which have many black players similarly have a problem with keeping sub-Saharan crime at bay, and this takes much of the luster off our athletic heroes. The National Football League even has an entire department dedicated to keeping sub-Sharan football players who go full thug out of the news. It’s tough to cheer for that.

This is the magic of Field of Dreams: It brings back a white league for white fans whose children can aspire to join or emulate the players. Ironically, this idea is articulated by the film’s only black character, James Earl Jones as Thomas Mann:

Ray, people will come, Ray. They’ll come to Iowa for reasons they can’t even fathom. They’ll turn up your driveway, not knowing for sure why they’re doing it. They’ll arrive at your door as innocent as children, longing for the past. “Of course, we won’t mind if you have a look around,” you’ll say. “It’s only 20 dollars per person.” They’ll pass over the money without even thinking about it; for it is money they have and peace they lack. And they’ll walk out to the bleachers and sit in shirt-sleeves on a perfect afternoon. They’ll find they have reserved seats somewhere along one of the baselines, where they sat when they were children and cheered their heroes. And they’ll watch the game, and it’ll be as if they’d dipped themselves in magic waters. The memories will be so thick, they’ll have to brush them away from their faces.

He is speaking of the memories of watching a sport whose players they can identify with. Field of Dreams isn’t just Kevin Costner in yet another baseball film, and the book is more than just a ghost story. Both works explore important themes: redemption, getting along in a new job, and separating that which is trivial from that which is truly important. And it unintentionally offers a temporary escape from the ongoing Great Replacement. Both the film and the book draw inspiration from an important cultural wellspring in America: baseball, the most American of sports.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 3

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

Are Whites Finally Waking Up?

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Birch Watchers

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

2 comments

Nice review. I strongly recommend the book and movie Eight Men Out. John Sayles did an excellent job putting it on the big screen. And it doesn’t ignore the huge Jewish influence in the 1919 scandal.

I don’t see Field of Dreams as any kind of right-wing movie, although the review makes strong points for it.

I also like Eight men Out. It’s one of the few films that really has a period feel, and does capture the corruption very well. Sayles makes a great Ring Lardner.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.