Our Prophet: Christopher Lasch’s The Revolt of the Elites, Part 1

Greg Johnson2,180 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here)

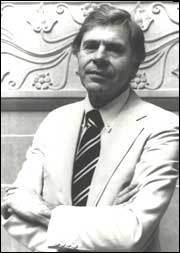

Christopher Lasch

The Revolt of the Elites & the Betrayal of Democracy

New York: W. W. Norton, 1995

Christopher Lasch (1932–1994) was an American historian who taught for many years at the University of Rochester, authored a number of important books, and spoke beyond academia to the broad, educated public.

Lasch has been described as a social critic and a moralist. This is true. But to me, he reads like a prophet: a prophet of National Populism, offering us a powerful critique of the current system and a wealth of surprisingly radical alternatives drawn from American history, all delivered in urgent, eloquent prose.

Along with Samuel Francis, Lasch is the person I most wish could have lived to see the age of Brexit and Trump. Lasch would surely have disliked many things about the new populism. But, unlike most critics of populism, at least he would have understood what he was dealing with. Beyond that, his criticisms would have been intelligent and helpful.

Throughout his career, Lasch was a critic of America’s professional-managerial elite and its liberal cosmopolitan ideology, albeit from two very different points of view. Lasch began his intellectual career as a Freudian and a neo-Marxist. But in the 1970s, Lasch’s explorations of vast but little-known tracts of nineteenth-century American intellectual history led him to reject progressivism in all its forms, both Left and Right. In place of progressivism, Lasch embraced both cultural conservatism (including a bold critique of feminism) and political populism (with its defense of a broad, productive middle class and its critique of cosmopolitan intellectual and financial elites).

Lasch’s best-known book is The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (New York: W. W. Norton, 1979), which sounds a lot better than it is, largely because its cultural criticism is blurred rather than sharpened by constant references to Freud and his school.

National Populists should begin with The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, a collection of highly accessible essays published after Lasch’s untimely death of cancer at the age of 61.[1] If you wish to explore the themes of The Revolt of the Elites in more depth, I recommend The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991), Lasch’s monumental critique of American progressivism from the point of view of nineteenth-century American populism. You will be astonished to discover that America once had a long, rich, and radical tradition of anti-liberal thought that National Populists can build upon today.

The Revolt of the Elites begins with an Introduction on “The Democratic Malaise,” and then falls into three parts. The first, “The Intensification of Social Divisions,” deals with the secession of the American elite from the American nation. The second, “Democratic Discourse in Decline,” deals with the conflict between experts armed with theories and common men armed with common sense. The third, “The Dark Night of the Soul,” distinguishes between religion and therapy.

Lasch begins by raising the question of whether American democracy can survive such social trends as “The decline of manufacturing; the shrinkage of the middle class; the growing numbers of the poor; the rising crime rate; the flourishing traffic in drugs; the decay of the cities . . .” (p. 3). Basically, these trends amount to the collapse of the middle class and the virtues prized by them: self-control, productiveness, and ordered liberty.

These fears immediately mark Lasch as a populist, which is to say: a modern descendant of classical republican thinkers like Aristotle, who held that popular government cannot survive without a strong middle class and a modicum of public virtue. These views were endorsed by Americans as eminent as Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, but they are scorned by advocates of “liberal” ideology, including present-day “liberal democrats.”

The “middle class” does not just mean “middle income.” It refers to a large number of self-employed small farmers, businessmen, and tradesmen. As Lasch notes, “Before the Civil War it was generally agreed, across a broad spectrum of political opinion, that democracy had no future in a nation of hirelings” (p. 81). Wage-earners, no matter what their income level, have less independence of mind than the self-employed. Being self-employed also develops such politically healthy virtues as self-discipline, personal agency, personal accountability, long-term planning, thinking in terms of production rather than merely consumption, and investment in the long-term health of the polity.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s Toward a New Nationalism here

Wise men from Aristotle to the American founders knew that the rich tend to be arrogant and greedy, and their rule tends to be predatory and tyrannical. They also knew that the poor tend toward slavishness and resentment, and when in power, they are as predatory as the rich, but their regimes tend toward anarchy rather than tyranny, largely because of short time-horizons. The middle class, however, prefers liberty over the tyranny of the rich and order over the anarchy of the poor. In short, they prefer ordered liberty. To secure ordered liberty from both extremes, the middle class must cultivate an ethos of civic participation. Freedom is not just minding one’s own business or doing what one pleases. It requires active participation in politics, including the willingness to take up arms for the defense of society.

If popular government depends on a broad middle class of self-employed producers, then the economy should be set up to promote and preserve such businesses rather than to undermine them. Thus small businesses should be protected from large corporations, even if large corporations produce goods more cheaply. Domestic industries should be protected from foreign ones, even if foreign imports are cheaper. Small farmers must be protected from large ones. Since small businesses often fail because they must mortgage themselves to get capital, money and credit policies should favor small businesses. Beyond that, even wage earners should be able to enjoy middle-class standards of living, which means protection from cheap labor, whether in the form of immigrants or cheap foreign goods.

These policies are collectivist, in that they constrain individual choice to secure freedom understood as popular self-government. These policies are nationalist, because they put the nation first, rather than the individual or the global economy. These policies are also “producerist” because they favor producers over consumers and financiers.

Liberalism, however, defines freedom as individual choice and decries any attempt to limit it as creeping tyranny. Consumers will always prefer cheaper goods. But these goods aren’t so cheap when you price in all the consequences. If small businessmen, tradesmen, and farmers go under because of price competition from big businesses and cheap foreign labor — or if middle-class producers are replaced by wage-earners who think only in terms of consumption — popular government will be destroyed by the tyranny of the rich and the anarchy of the poor.

As a consumer, you might benefit from cheap foreign goods. But you have to earn your disposable income somehow, and in the long run, none of us are immune to the logic of the global marketplace. How much money will you have for cheap consumer goods if you too are competing for your living with big businesses, cheap imported goods, and newly-arrived immigrants? And if you want to do something about it, you will find that as the economic power of the middle class diminishes, your political voice will diminish as well.

The problems that Lasch complained about in the nineties were already visible in the early seventies and have only intensified over the last 50 years. They have been allowed to fester, because America’s elites — the people who are most able to fix them — don’t think they are problems, or their preferred solutions don’t actually work. In fact, all these problems are the inevitable consequences of the elites’ philosophy, self-image, and policy preferences.

According to Lasch, our ruling elite encompasses more than just the political class, the bureaucracy, and the rich, but also “corporate managers” and “all those professions that produce and manipulate information” (p. 5), i.e., the professional-managerial class (PMCs for short). Politicians and businessmen can be quite rooted, nationalistic, and patriotic. But PMCs are “far more cosmopolitan, or at least more restless and migratory, than their predecessors” (p. 5).

In The True and Only Heaven, Lasch argues that PMC cosmopolitanism is ultimately rooted in the Enlightenment idea that all of society can be modeled on modern natural science, which knows no borders and aims to relentlessly replace diverse myths and opinions with universal knowledge. This would imply that the consciousness and ethos of the professional-managerial class ultimately derive from academia, specifically the modern “research university.” This would explain why the cosmopolitanism and rationalism associated with the PMCs came to set the tone for the ruling elite as a whole: They all went to the same colleges.

The cosmopolitan self-image leads to a disdain for nationalism and an embrace of multiculturalism and economic globalization, which really amount to the same thing: the world remade as a shopping mall. Lasch observes that

Patriotism . . . does not rank very high in [the PMC] hierarchy of virtues. “Multiculturalism,” on the other hand, suits them to perfection, conjuring up the agreeable image of a global bazaar in which exotic cuisines, exotic styles of dress, exotic music, exotic tribal customs can be savored indiscriminately, with no questions asked and no commitments required. . . . Theirs is essentially a tourist’s view of the world . . . (p. 6)

But global capitalism leads inexorably to deindustrialization and the decline of the middle class, which first hits the lower middle class and well-paid members of the working class. Those vibrant new immigrants also need to live somewhere, usually somewhere cheap, which means lower-middle-class urban areas.

But shopping amidst diversity is not the same as living with it. As lower-middle-class neighborhoods become more diverse, public spaces become alienating and degraded. The value of housing, the single biggest investment for most lower-middle-class Americans, begins to decline, and white flight begins.

Typical scribes, PMCs also prefer clean jobs over dirty ones. All those unemployed steelworkers and coal miners can simply get jobs in the “information economy.” If they don’t, that’s their problem. (Unless, of course, you are non-white, then your failures are the fault of white people, including those white losers the elites wash their hands of.)

But what about our ruling elite’s commitment to equality and democracy? How do they square that with policies that will inevitably pauperize the vast majority of their fellow citizens? It doesn’t bother them, because as cosmopolitans, they don’t have any particular attachment to their “fellow citizens.” Besides, globalization is egalitarian: the global market means a global price, which means rising standards of living for most of the globe. American workers lose out only because they are overpriced, but open borders and global trade will rob them of their unfair advantages. Globalization allows our elites to gut the American middle class for cheap labor and goods, while feeling terribly virtuous at the same time.

Even though our current elites have condemned the vast majority of their fellow citizens to downward mobility, they also preen about their openness to “the selective promotion of non-elites into the professional-managerial class” (p. 5). PMC upward mobility comes in Right-wing and Left-wing versions. The Right-wing version is meritocratic, meaning that promotion is based on objective, job-related criteria. The Left-wing version is more sentimental, stressing upward mobility for previously marginalized groups, which they presume all aspire to live like contemporary PMCs.

But, as Lasch points out, “Social mobility does not undermine the influence of elites; if anything, it helps to solidify their influence by supporting the illusion that it rests solely on merit” (p. 41). Selective upward mobility allows PMCs to legitimize a system that condemns most of their fellow citizens to Third-World poverty and powerlessness. It lets them tell globalization’s losers that if they fail to prosper in the new economy, they have only themselves to blame.

There is a deep smugness, snobbery, and sense of entitlement among PMCs. For instance, it never occurs to them that globalization might lead to downward mobility for their class. They are convinced they represent the end point of history and the true aspiration of all mankind, which may explain their hysteria over reversals like Trump and Brexit. They are “the best and the brightest.” The arc of history doesn’t just bend toward their supremacy, it bows down before them. How dare the vulgar masses reject their leadership?

The humanitarian pretenses of a class that condemns the vast majority of its fellow citizens to penury and oppression are obviously quite thin, and Lasch is merciless in exposing them. He argues that “The culture wars that have convulsed America since the sixties are best understood as a form of class warfare” (p. 21). He also notes that when PMC reformers face resistance,

they betray the venomous hatred that lies not far beneath the smiling face of upper-middle-class benevolence. . . . They become petulant, self-righteous, intolerant . . . Simultaneously arrogant and insecure, the new elites, the professional classes in particular, regards the masses with mingled scorn and apprehension. (p. 28)

Can we really expect good government from people who hate us?

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Note

[1] Another important posthumous collection of essays is Christopher Lasch, Women and the Common Life: Love, Marriage, and Feminism (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997).

Our%20Prophet%3A%20Christopher%20Lasch%E2%80%99s%20The%20Revolt%20of%20the%20Elites%2C%20Part%201

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 3

-

Democracy: Its Uses and Annoying Bits

-

Bottled Up

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 584: The Counter-Currents Book Club — Jim Goad’s Whiteness: The Original Sin

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 5: Refleksje nad Pojęciem polityczności Carla Schmitta

-

Remembering Bill Hopkins

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 4: Teoria i praktyka

13 comments

I read this book several years ago. I thoroughly enjoyed it, think it aged rather well, but had subsequently forgotten about it. Thanks for the great reminder and summary Greg.

I once started Culture of Narcissism but was put off by the Freudian psychobabble. I’ll have to read Revolt. This reflection on the “professional” as a global ruling class or type sounds compelling. Zman sometimes talks about someone named Burnham who addressed a similar phenomenon. Prior to both of these we have Ernst Juenger’s account of the “Worker” as the ruling typus that dominates in the service of groundless global norms and goals that have no determinate end but the expansion of power and control, and no attachment to any particular people, place, or land. The typus of the worker or “professional” replaces the bourgeois “individual” with his illusory belief in his “rights” and “merit.” This era of universal compliance with global covid rules (vaccinations, lockdowns) and the DEI regime etc. is evidence that the age of this individual is over with, and for the truth of EJ’s perspective more generally.

But thanks for this very interesting review and book recommendation.

Yes, Zman does talk about Burnham but the main thing I remember about Burnham comes from Sam Francis. According to Sam Francis, Burnham showed how there was a revolution in America in which the managerial class took control of business away from the actual creators of business.

Wonderful essay. I really enjoy when Greg puts the pieces together across the centuries to tell our story. Lots of people poo-poo the 60s and 70s but Lasch is not the only good thinker from that era. Lots of them drank the anti-White Kool-Aid, though, so many on the Right wouldn’t give them the time of day. Still, thinkers like Theodore Roszak and Kirkpatrick Sale have worthwhile things to say. They’re just dumb on race. And being dumb on race means a good deal of their ideas are rubbish. But not all.

It sounds like the author really got the picture.

I read The Revolt of the Elites a couple years ago. The thing that impressed me was that while the book was written back in the 1990s it pretty much describes how things were playing out in 2020 with the alienated overclass, the globalism, the spiral of consumerism, the assault on middle America.

What perhaps is needed is The Revolt of the Populists.

“Revolt of the Elites” was in reply to Ortega y Gasset’s “Revolt of the Masses”

I have to disagree with these heuristics. America was never a ‘middle class’ country besides the postwar interlude (American Hiraeth) called the ‘the 1950s,’ which was a completely artificial construct gifted by the US government to white men for slaying nationalism abroad. The ‘middle class’ is as arbitrary in America as ‘race’ is in Latin America. If you make $10k mopping floors or $150k a year crunching numbers in Manhattan you can *choose* to identify as middle class. If you make $40k and work from sunup to sundown with mud on your boots, you can also *choose* to be middle class.

Meanwhile, in Latin America you can have no hint of European ancestry, yet you can decide to *become* white by relocating from some shack in the Andes to the Peruvian coast, shedding your derby hat and speaking a certain dialect of Spanish.

America was founded as a country of Jeffersonian yeomen. Until the turn of the 20th century the vast majority of people were impoverished subsistence-farmers.

As for nationalism, patriotism and multiculturalism, it comes in cycles regardless of economics. Even people who are racially-aware insofar as revealed preference (mating, networking, suburbanizing etc) still genuinely forget casual differences in disposition between the races because of normalcy bias (rather than the myth of ‘pathological altruism’ or the colorblind affectation).

They forget the industrial black violence of the 1970s-1990s because the Clinton Crime Bill and the Giuliani ‘stop-and-frisk’ (gun-control) swept an entire generation of black youths off the streets, instantly putting an end to the cartoonish violence that inspired an entire genre of film based in NYC alone (The Warriors, Bonfire of the Vanities, Escape From New York, Death Wish etc).

So that’s the only reason why ‘multiculturalism’ is ever momentarily embraced. Much to the delight of elitists, whites forget that blacks are randomly and brazenly violent in public because of high-time preference, which they have since reverted back to since the 2020-present black crime wave, or that matriarchy and illegitimacy is the default setting of black culture without Jim Crow, not ‘Muh welfare.’

Now whites suddenly remember blacks are a clear-and-present-danger by merely crossing paths in the subway, and are a national emergency on the aggregate even though they had been relatively inactive for 25 years. This recrudescence is quietly met with white recourse that expresses itself in populist landslide elections and periodic white flight to relocate and recreate their own white economic-zones to circumvent urban multiculturalism or greatly diminish its encroachment, much to the chagrin of elites.

You write “America was never a ‘middle class’ country besides the postwar interlude (American Hiraeth) called the ‘the 1950s,”

It seems to me that in the 1920s under Harding and Coolidge (especially Coolidge”), it was a middle class country. See details in Paul Johnson’s “Modern Times”.

And how did that turn out on October 24th 1929 and for the next generation after that? My point stands. America was never a middle class country. It isn’t one today.

You are using middle class as “middle income” not independent farmer, businessman, trapper, tradesman, etc. which is the relevant definition.

That’s what middle class and ‘bourgeois’ is though. People in England speak with a certain affected dialect (almost comparable to Ebonics) depending on their income, which means whether or not they ‘work with their hands,’ and thus their entire class identity forms this algorithm of what political party they support, to what neighborhood they live in, whom they marry, fraternize with, how they dress, speak and what they eat, what music they like or what football club they root for.

Meanwhile, in America we have extremely socioeconomically-diverse neighborhoods behind the racial segregation, where neighbors have literally no idea (or concern) what profession or income their neighbor has or anything else. All they care about is matching phenotypes and respect for private property (eminent-domain).

All of these professions you listed were historically precarious. That is not a middle-class trait, which is grounded in the artificial stability from labor unions and protectionist lobbyists, and only formed after these professions were no longer hounded by Pinkerton strikebreakers deep into the 20th century. I could write a book on how the entire 1950s was created by socialism and WWII, yet it somehow became the frame of reference for free-market Americanism. The average lifespan was 57 years old when the New Deal was passed even though the Social Security Act made retirement at 65 (clearly designed as a Ponzi scheme).

The vast majority, perhaps supermajority, of America would be considered impoverished until after WWII. The short lifespans and lack of obesity demonstrates this. So whatever merchant class you are thinking about was an insubstantial strata.

You have a good point and the one thing that Harding and Coolidge didn’t do was the old Andrew Jackson trick, i.e. End the Fed. There are always booms and busts and government intervention is what prolongs them. There was a big recession in 1920 and Harding ended it by cutting both taxes AND SPENDING. Had Coolidge run again in 1928, he surely would have done the same. Instead we got Hoover who was no different than FDR and tried to fight the depression with massive government programs. All this did was prolong the depression. If we could have Ron Paul time-travel back to 1929 and make him president, he would have done a better job that even Silent Cal would have done had he remained in office in 1929. Cut government spending, cut taxes and END THE FED.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment