Grosse Freiheit Nummer 7:

The Best German Film on World War II?

Steven Clark

When we think about Third Reich films, we always go to the usual: Triumph of the Will, Der Ewige Jude, Jud Süß, and Kolberg, Goebbels’ final, fist-shaking epic call to resistance as the Reich crumbled. Yet, German film a the time was quite varied, innovative, entertaining, and more than just propaganda films for the master race. Jewish writer Walter Laqueur observed that German film had a worldwide reputation in the 1920’s and ’30s, and even in the Nazi era films were made with a high level of competence and had considerable entertainment value. Unlike the other arts, movies under Hitler were given a great deal of latitude.

There were only a handful of overtly anti-Semitic films, primarily those named above. Goebbels wanted German film to be optimistic, emphasizing pleasant subjects and diversions rather than hard National Socialist doctrine, as he realized that the people were more amenable to Hitler’s message when it wasn’t drummed into them.

Grosse Freiheit Nummer 7 , made in 1944, has a message, but it’s subtle, human, and quite cinematic.

First, there is the odd-sounding title. The film takes place in Hamburg, Germany’s major port, and Grosse Freiheit means “great Freedom .” Hamburg, being a Hanseatic and commercial city, was also a Protestant one, but ports and commerce inevitably dull true faith, and Grosse Freiheit was a street where practicing Catholics were permitted to reside in devout Lutheran Hamburg. This freedom loosened over time where the street became part of the Reeperbahn, Hamburg’s traditional red-light district.

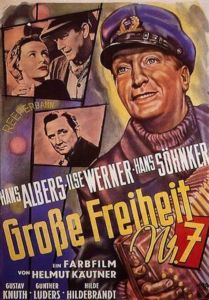

Director Helmut Kautner’s film has a great deal of charm with Hans Albers as its leading man. Bearing a resemblance to the American actor George C. Scott, Albers was a distinguished performer, appearing in dozens of films across a wide range, from comedy to adventure. Albers even did a turn as Sherlock Holmes. He also played Baron Munchausen in the high-budget fantasy Munchausen (1943). In Grosse Freiheit Nummer 7, Albers is Jannes, a “singing sailor” who performs at a Hamburg nightclub. He is a rugged sailor who decided to remain on land, where he’s the main attraction. A trio of shipmates from the Padua, the majestic sailing ship Jannes once served on, are on leave and pop in to see him, amused by a mannequin of Jannes in front of the club that is dressed in seaman’s cap and coat, holding an accordion.

Jannes is the life of the party: a charmer and the main draw to the club. It’s a place where the girls are there to milk the sailors — but in a mild way. There’s also an inner circle where patrons — especially women — ride a merry-go-round that might recall the attempts of men to court women, or perhaps Jannes’ life at this stage.

Anita (Hilde Hildebrand) owns the club, and has an off-and-on romance with Jannes, treating him well as he’s the main attraction, always in demand for a song. This club is an interesting contrast to the Kit-Kat Club in the film Cabaret, which offers more degenerate parties in the full range of Weimar decadence. This show, however, is relatively clean. There are drunks, women hustling men, bawdiness, and a fight or two, but it’s all quite normal. Similar to Cabaret, there are songs in this film, but they’re integrated into the action in Brechtian fashion, so there are no big show numbers. Jannes does the singing while he plays the accordion, and the Gemutlichkeit is a worker’s kind of place. Jannes sings of love, parting, Hamburg, the sea — and the audience loves it.

Anita looks at Jannes with a mixture of adoration and sangfroid. She warns the girls, “He’s always nice at first, but he’ll leave. . . . The women come and go, and that’s how it is.” Yet, she thinks she’s kept Jannes away from the sea for good. He’s also being wooed by a fancier nightclub, so she has a wage a two-front war to keep him from walking.

Jannes’ former shipmates try to get him to sign up, but he’s content being the life of the club. Albers plays a mean accordion, and his character is a main attraction on the Reeperbahn. How could he give it up?

But then he receives a message he doesn’t want to reply to. His brother is dying, and Jannes reluctantly visits him in the country. His brother is disliked, being a reprobate and scoundrel who is now bedridden from blackwater fever, a form of malaria no doubt contracted during his sailing days.

Jannes is angry. His brother stole money that Jannes had saved so he could go to the maritime academy to train as a helmsman. Jannes did it anyway, but he rages at his brother, who is now barely able to speak but whose eyes burn into Jannes. He makes a last request: Gisa Hauptlein, his lover, needs to get out of town, and he asks Jannes to escort her to Hamburg. Gisa (Ilse Werner) is beautiful, but not flashy. She is denounced by her mother for immoral behavior in staying with Jannes’ brother, and Gisa is sharp to Jannes. He doesn’t want to be lumbered by her, but sees that the village has turned against Gisa, and he reluctantly agrees to take her.

“Do you mind coming?” he asks her. “Where else would I go?” she shoots back.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

She also is tired of her mother’s carping, glad to leave the village and get some peace after all the accusations. Gisa is stern as she tells her mother off: “You listen to strangers more than your own child.”

A German saying, “Stadtluft macht frei” — city air makes you free — is demonstrated when Gisa comes to Hamburg and stays in Jannes’ spare room, getting a job in a haberdashery. She brightens, and Jannes finds himself caught in her charm and she cleans his place up. Gisa sees Jannes more as a protector than as a lover, but she warms to him. She starts to stir his heart, and he wonders if he’s missed out on something in life by not marrying. He laughs off the postcards of naked women she finds (which are very graphic; not of the sort that Hollywood would have shown then). He renames Gisa La Paloma, after the song — and of course Jannes sings it in the club. He’s a changed man, and his shipmates notice it. So does a troubled Anita.

Enter Georg, who is shopping for a tie, banters with Gisa, and remains tieless for most of the film until he finds the right one. He’s a terrible dresser, wearing a floppy cap and investing his Reichsmarks in a flashy white suit. But Georg is determined, has his own stride, and romances Gisa. Unlike Jannes, Georg works at a shipyard, and a subtle battle between a romantic sailor and a factory worker ensues.

Grosse Freiheit is a working-class drama, totally in sync with National Socialist doctrine, but also reflecting much of America or any urban setting. These are little people, but the acting and characters make them strong and compelling. Georg always seems to get off on the wrong foot, but he’s persuasive, and Gisa is slowly drawn to him.

Jannes, while strong, noble, and devoted, is older, and will always remain a father figure, while Georg is her age, and has a breeziness that softens her. Jannes decides to ask Gisa to marry him, and as he prepares an elaborate dinner, Gisa goes to bed with Georg., and we see them naked in bed together. It breaks Jannes’ heart, but it’s inevitable, and his life ends up resembling the love ballads Jannes sings about: men must move on, women are all alike, and so on.

There is a long dream sequence i which Jannes’ life is hashed out. He becomes the mannequin in front of the club. Is he man or mannequin? Is art real or a trap? He wakes up, accidentally smashes a ship in a bottle that he had laboriously built, and despite Anita’s pleas, he takes an open spot on the Padua and sails off, leaving Gisa and Georg together.

In the end, Jannes is again at sea, no longer with his accordion and seaman’s blazer but in rough weather gear as a helmsman, guiding the ship. He’s happy.

In effect, what is important to a man like Jannes? Showbiz or reality? Cabaret would answer “showbiz,” as such films are a glorification of illusion and the view that our true selves are molded through that illusion. In Cabaret Sally Bowles, the carefree show girl, aborts her own child so that the show can go on, whereas Jannes is a working-class hero; in the end, he must fulfill his duty.

The film is quite ordinary in its structure and characters, but Grosse Freiheit Nummer 7 succeeds in no small part due to its cast. Hans Albers is sympathetic: an ordinary man who bows to no one, as well as an artist and a sailor. His choice, wherever he goes, is strong. The rest of the cast also does well. Ilse Werner is at once attractive and tempting in that sedate, understated European way. She lacks the Hollywood glamour we see in American films from this period, but possesses that European sense of quiet strength.

I say it’s the best German World War II movie because it is about ordinary people, and there is little, if any, propaganda about the nobility of race or struggle, nor is there stern defiance before an enemy. The movie’s background never lets you know if the war is going on or not. It’s also an anachronism that the Padua is a sailing ship, but it fits into the story’s romantic nature and almost seems a reverse of the Flying Dutchman legend. Jannes doesn’t need a woman’s love to redeem him, as he’s his own man.

The making of the film had an interesting history. It had to be shot in Berlin, Prague, and Hamburg in order to find cityscapes that were free of war damage, and the scenes set in Hamburg’s harbor involved a lot of trickery and cutting to conceal the signs of war. Goebbels grew hostile to the film during its production, insisting on script changes. Jannes was originally named Jonny, but this was changed to make him more German. Even this didn’t satisfy him, however, and Goebbels refused to release the film in Germany. It opened in German-occupied territories such as Prague, but never got much distribution in Germany itself until after the war. Then it became an immediate favorite with German audiences and has remained so, and is considered one of the best German films of the 1940s.

If one wants to see Jannes as an Aryan hero, one is free to do so. He’s a strong character, going from swagger to remorse, anger to delight. This is also very much in sync with cinematic trends, where downbeat, working-class themes began to predominate in cinema,. The thirties’ glamour had run its course.

As for the difficulties in making the film, I’m reminded of Michel Carne’s 1945 French film Les Enfants des Paradis, another story about show folk and reality that faced considerable challenges over two years due to the war.

You can watch Grosse Freiheit Nummer 7 online, and it’s been remastered in splendid color that is beautiful. The lack of a specific time period adds to its timelessness. Also notable is the fluid style of Kautner’s camera work. The camera zooms and pans toward certain characters when they speak, and again, the story depicts the general wants and needs of ordinary people. Thelove triangle here is presented with all three characters equally balanced. It’s also a contrast to the destructive nature of nightclub cabaret life that is depicted in Der Blaue Engel, for example. Jannes, Gisa, and Georg all find their own destinies and place in the world. No one is corrupting or subverting the others.

Interestingly enough, Hans Albers played Mazeppa in Der Blaue Engel, and the Padua was an actual German sailing ship that was confiscated by the Soviets after the war and renamed.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.

Grosse%20Freiheit%20Nummer%207%3A%0AThe%20Best%20German%20Film%20on%20World%20War%20II%3F%0A

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 3

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 2

-

Think about It: Michael Nehls’ The Indoctrinated Brain, Part 1

-

Democracy: Its Uses and Annoying Bits

-

Looking for Anne and Finding Meyer, a Follow-Up

-

The Origins of Western Philosophy: Diogenes Laertius

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy, Rozdział 6: Znaczenie filozofii dla zmiany politycznej

-

Elizabeth Dilling on the Evil of the Talmud

5 comments

Thank you. This is something I never thought about before.

Corrected URL for the film:

https://archive.org/details/GrosseFreiheitNr.7-1944

Thank you. Will have a look.

Thanks for the links and the review. I’m enjoying watching the film which reminds me a bit of It’s a Wonderful Life in terms of the coloration and the innocence of the relationships between the characters; standing in distinct contrast with usual Hollywood fare.

Although sail was clearly on its way out, the Padua was, as you say, a real ship, a huge 3000 ton four-masted windjammer built in 1926 in Bremerhaven, the last of the line. Such ships were especially suited to carrying grain from Australia to Europe, due to the great distance and lack of coaling stations which is referenced early in the film when one of Jannes’ friends boasts of a run from Spencer’s Gulf ( in South Australia ). Padua’s sister ships in the ‘P’ line, Pamir and Passat, continued to carry grain from South Australia until 1949. The Pamir was lost at sea in 1957 and the Passat retired the same year. The Padua , taken as a prize in 1946, is still afloat today as the Kruzenshtern and in use in Russia as a survey and training vessel.

Thanks for this interesting review that motivated me immediately to search within my old DVDs for the film. I have just a small annotation to make: The name of the main character played by Hans Albers is Hannes (not Jannes).

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.