2,032 words

Something remarkable happened in Finland during the First World War: The Finns made their homeland an independent state for the first time in their history when the Russian Empire fell apart in 1917. Then they defeated the Bolshevik government in a bitter civil war, and succeeded in maintaining their independence from the Soviet empire during the Second World War.

The story of Finland’s independence and its rise to the status of First World nation is an uplifting tale, and it is a roadmap for American white advocates to consider as they seek to set their own nation free of the Empire of Nothing and its ideology of Negro Worship, as well as resist a resurgent Russia.

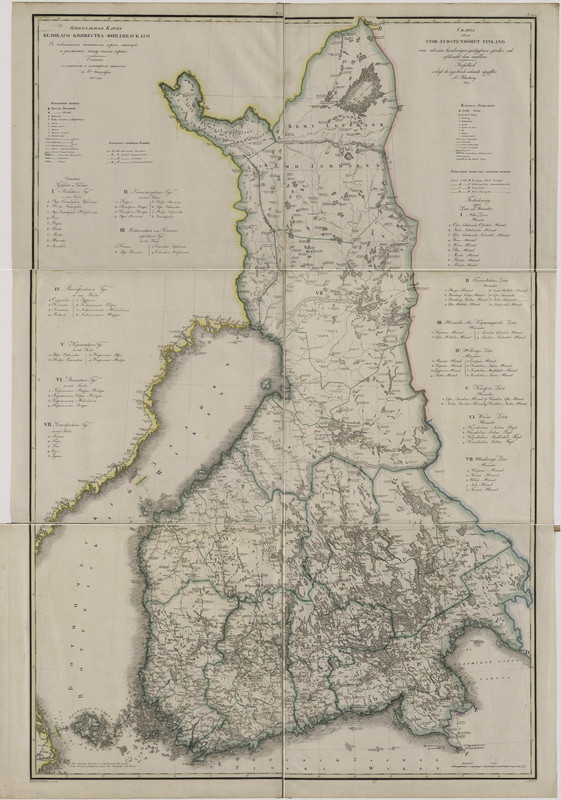

The growth of the Russian Empire. During Mannerheim’s career in the Russian Cavalry, the Russian Empire had expanded into Manchuria.

At the center of Finland’s rise to independence and freedom is Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, who was born on June 4, 1867. Mannerheim was part of the Swedish-speaking minority in the coastal regions of southern and western Finland. He was from a noble family and held the rank of Baron.

Mannerheim was not just a Finnish aristocrat; he was also part of the wider Russian nobility within the Tsarist structure. Finland and its nobility were incorporated into the Russian Empire in the early nineteenth century. For more than a century, Finland was a semi-independent Grand Duchy, with the Russian Tsar serving as the Grand Duke. Finland had its own parliament and its own military, but any Finn could join the Russian imperial project should they wish to do so.

Ironically, Mannerheim’s career as a Finnish ethnonationalist leader started when he joined the Russian cavalry. He was forced to do so after being expelled from the Finnish military academy for being away without leave for a night. His first notable accomplishment in the Russian military was marching in Tsar Nicholas II’s coronation parade in 1896.

Carl Mannerheim is the cavalry officer to the left of Tsar Nicholas II. Mannerheim is looking to his right.

In retrospect, the coronation was a harbinger for the disasters that plagued Nicholas’ reign. There was a crowd crush which killed and injured thousands of people who had come to see the event as well as acquire some souvenirs.

A few years after Tsar Nicholas’ coronation, Russia embarked on a Russification campaign in Finland which took place in two separate pushes. The first began in 1899 with the modification of various laws, the three most egregious being that Russian speakers were given priorities in civil service jobs, the Finnish military fell increasingly under the control of Imperial Russia, and the Russian language was declared the language of administration in Finland. This ended in 1905, but a second push began in 1908.

The Finns did not rebel because of these measures; Russian power was too strong. But the Russians were on the cusp of making several mistakes which the Finns used to their own benefit.

The first mistake came in 1905, when Japan went to war with Russia in the Far East. Russian forces were supplied by the Trans-Siberian railroad. In the summer months, materiel traveling on it had to be downloaded, boated over Lake Baikal, and then re-uploaded on the other shore. This was a major logistical bottleneck. Additionally, trains carrying supplies east were forced to stop as those carrying wounded men home were coming west. The Japanese, by contrast, had shorter supply lines and a very efficient military that easily defeated the Russians. Mannerheim served as a Lieutenant Colonel of cavalry during this war, and had a horse shot out from under him.

After his service in Manchuria, Mannerheim was detailed to travel to China to assess the situation there. He traveled across Kazakhstan and entered China via the same pass which the Mongols had used to invade Russia in the 1200s. There, he found that the opium crisis was in full swing. Even the officers of the Chinese border force were heavy opium users, along with many of the soldiers and government officials. Thus, in 1906 Chinese society was at rock bottom.

Upon his return to Russia, Mannerheim became commander of cavalry in Poland, which was then part of the Russian Empire. Mannerheim undertook a policy of military reform, taking the lessons learned from the Russo-Japanese War and applying them to the Polish cavalry.

Polish-speakers in the Russian Empire in 1916. On the eve of the First World War, Poland was far more Russified than Finland, but the tensions between Poles and Russians were severe.

Mannerheim was acutely aware of the tensions between the Poles and Russians. He later wrote:

In spite of my position in the Russian Army, the Poles received me without prejudice. As a Finn, and convinced opponent of Russia’s Russification in my own country, I could understand and sympathize with the Poles, but I never discussed politics with then. Nor did they on their side even break this tacit understanding, which was a kind of freemasonry without vows. Their attitude towards Russia was very similar to ours, though Poland found herself in a different position to Finland after her two revolts in 1831 and 1863, which especially the former, had been crushed with extreme harshness. The Polish kingdom created by Alexander I had been gradually shorn of its privileges until it had become a Russian province, with Russian the official language and schools and administration Russianized. Outwardly no Poland remained, but Polish patriotism burned all the fiercer under the surface.[1]

When the First World War broke out, Mannerheim commanded his cavalry well, but the war went badly for the Russians. Russian society was still recovering from the shock of the Russo-Japanese War; its economy had barely recovered, and its domestic politics was unstable — and revolutionaries were everywhere.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s Toward a New Nationalism here

Mannerheim was at the front lines, so he was not fully aware of how bad the domestic situation in Russia had become. He got an inkling when he visited the Tsar’s family. He had a long chat with Tsarina Alexandra while on leave. He found her “frail and her hair . . . greyer then when [he] had seen her last.”[2] Her son also informed him of an ally’s defection to the enemy: Colonel Sturdza, a Romanian.

This was a shock to Mannerheim. It was clear that events in Russia were spiraling out of control. When the Revolution came, Mannerheim was in Odessa, recovering from an injury sustained in a fall. While there, he visited a fortune teller who said he would eventually lead a victorious army. He then resolved to return to Finland. He and several other soldiers traveled by train to Saint Petersburg (then Petrograd), and he wore his Tsarist uniform throughout the journey.

Mannerheim met with several high-ranking members of the Tsar’s family in Petrograd. None thought that it was possible to beat the Bolsheviks. With the exception of Britain, Europe’s royal families were making poor decisions. Franz Ferdinand became the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire only because the son of the reigning Emperor had died in a suicide pact with his mistress in 1889. Many of the Romanovs were likewise involved in questionable personal conduct, and rumors of homosexuality and affairs were rampant. Tsarina Alexandra’s support of Rasputin, for example, was a major public relations disaster.

But the worst decision of the war was made by Tsar Nicholas II, when he decided to go to war in 1914. He further exacerbated the problem by assuming personal command of the Russian army. As a result, he went to a forward headquarters, leaving him out of touch with domestic political events. It also made him personally responsible for every misfortune the Russian army experienced in the eyes of the public — and there were many.

Mannerheim arrived in Finland as the Russian Civil War was breaking out. The Bolshevik Revolution had spread to Finland, but it didn’t have the same level of support there. As an aristocrat with a career’s worth of high-level military experience, he was immediately tapped by the Finnish Whites for service in the war.

Mannerheim’s White Army quickly filled with volunteers. He found that improvisation and non-military experience were important in the conflict. “Successful work in the civil service, in industry, or in commerce was in some cases a better preparation for the kind of jobs the war called for,” he wrote. He recognized the military mind’s limitations: titles, ribbons, and rank are well enough for an established force carrying out a limited campaign, but in a revolution atop a war for national liberation, much more was called for.

Finnish resistance to the Bolsheviks mainly came from Finnish society’s middle and upper ranks. The main organization to which Mannerheim answered was the Military Committee, which was badly organized and dysfunctional in January 1918. It had convened in three different locations due to their sense of insecurity. Mannerheim recognized that the Committee had tabled a discussion about an attack on a Russian-held fort when such an attack would have brought about grave consequences no matter its outcome. He advised the Committee to move immediately to a permanent secure location, issue a call to arms to the Finnish people, and accept foreign arms and support — but advised them not call for foreign troops. Mannerheim wanted Finland’s war of liberation to be waged by Finns alone.

The Reds in Finland consisted of Russian soldiers garrisoned in various places across the country, as well as Finnish Communist sympathizers.

The Military Committee accepted the recommendations and Mannerheim moved to Vaasa — although barely made it there. He was stopped by Russian soldiers and only allowed to proceed when a Swedish-speaking youth who worked for the railroad insisted that his pass was in order. Mannerheim then gathered a force of veteran soldiers and attacked the Russian garrison at Vaasa, capturing large caches of weapons and ammunition. His forces also captured the port of Tornio in the north.

The Finnish White Army was now a genuine force. It was centered on a regiment which had seen service with the Germans: the 27th Jäger Battalion. Mannerheim had two critical assets: he had the support of the Finnish bankers, who moved gold reserves to the areas he secured, and extended credit to his forces; and he received the support of the German military as well.

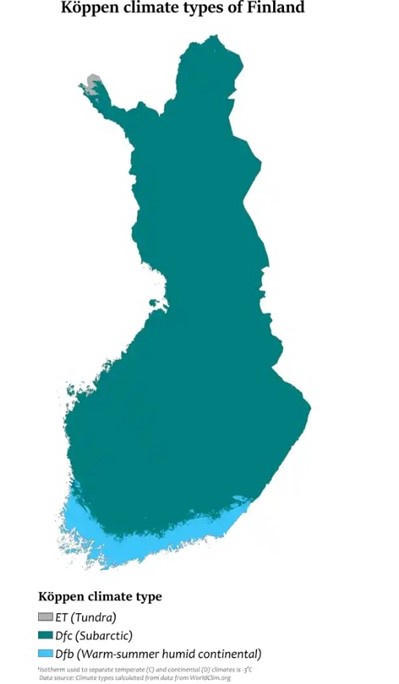

The war soon became a one-sided affair. The Reds controlled the most important areas of Finland, but they were disorganized and lacked support from the broader Finnish population. The hostility to the earlier Russification efforts likewise made many Finns hostile to Bolshevik ideology, given that it originated in Russia. The White Army and their German military allies thus moved south and conquered the Red forces within a little more than three months.

Despite the war’s short duration, it was extremely cruel. Captured Red prisoners were massacred by White Army soldiers. Finland then briefly had a King, who came from the Prussian royal family, but as Germany’s position in the World War deteriorated, so too did the King’s fortunes.

Mannerheim was frustrated with Germany’s support. He wanted to take the war to Petrograd and capture the Karelian Isthmus, but the Germans were negotiating with the Bolshevik government and wanted to end their hostilities with Russia. This clipped Finnish ambitions. Mannerheim was also critical of the White Russians, as he found that their senior leaders lacked focus and drive.

Once the war ended, Finnish society became far Left economically, but was not Communist. The Finns were invaded by the Soviet Union in 1939, although they were triumphant through gallant resistance and compromise, and then invaded the Soviet Union between 1941 and 1944 with German support. Officially neutral during the Cold War, they were nevertheless dominated by their giant neighbor, but never sacrificed their independence.

Mannerheim was a stalwart soldier in the Russian Imperial Army until the thread that bound him to the Tsar broke. Then he became a hard-headed, far-thinking Finnish patriot.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Bibliography

Hourly History, Finnish Civil War: A History from Beginning to End, 2022.

Notes

[1] Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, The Memoirs of Marshall Mannerheim (New York: E. P. Dutton & Company, 1954), pp. 76-77.

[2] Ibid., p. 108.

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Pro-Natalist Policies

-

Elizabeth Dilling on the Evil of the Talmud

-

The Significant and Decisive Influence that Leads to Wars

-

Crusading for Christ and Country: The Life and Work of Lieutenant Colonel “Jack” Mohr

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

On Second World War Fetishism

-

Communist Barbarism in Hungary — and America Today: When Israel Is King

-

The Establishment’s Radicals

10 comments

Thank you for this very informative article.

There is a fine little story of Mannerheim’s loyalty and his honoring of vows. Even though Finland had been independent for years, Mannerheim kept a portrait of Tsar Nicholas II in his office. When asked why, he famously replied that ‘he was his Tsar’. Even though the Tsar had been murdered years ago and Mannerheim himself led his nation in a civil war to a fully realized independce, he still held respect for the man whom he had swore to protect and serve.

Mannerheim had served in the Chevalier Guard Regiment and knew the imperial court well. He thus knew Russia’s allies too, and was very fond of the French and British, which put him in opposition with most Finnish Whites, who preferred the Germans, thanks to their support and training of Finnish troops within the Jäger movement. When Finland aligned itself with Germany once again in 1941, this put new strains on Mannerheim, who was very fond of Winston Churchill. Churchill himself was sorry about the fact that he had to declare war on Finland, as the two men held each other in great respect. And once Finland withdrew from the Axis side, Mannerheim’s contacts in the West became once again helpful.

Yes, instead of negotiating peace, Churchill had to declare war on Finland or he would have likely lost his beloved Chartwell and quite possibly his exalted station and even his wife Clementine. The ‘Focus’ loan made at the behest of the Jewish Board of Deputies left Winston beholden to them and turned him into a stooge for the international comspiracy to stifle the European rebellion led by Germany.

Great essay.

Nice essay. How does this apply to our situation? We are the imperial power not a distant vassal.

American whites are in a similar position to Finns in the Russian Empire.

1. The interests of the American Empire do not align with the interests of American whites.

2. The leadership of the American Empire is seeking to replace American culture with that of Negro Worship. An example of this is removing monuments and adding holidays such as Juneteenth. This is like the Russification policy in Finland.

3. America is getting involved in foreign conflicts in a reckless manner – such as Russia’s decision to go to war in 1914 over events in Serbia.

4. American economic policy is rigged in such a way that allies who are protected by American security guarantees are able to acquire industry from the American heartland.

Thank you for clarification. Point #4 is astounding in its masochism.

Is there a parallel in terms of an American military leader who goes to fight for the GAE (Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia … …) and returns to find himself replaced in his own country? It wouldn’t be a leader as they don’t fight and they are paid handsomely by the system. I guess time will tell if it is a group of rank and file.

Thanks for the essay and doing the research to put it together.

Thanks for this little piece of history.

sounds like a class war, not national.

This is really wonderful. I remember coming across Mannerheim many years ago while thumbing through an old LIFE. A very proud and stately portrait of the elderly officer who was then winning the Winter War (early 1940) against the Soviet invaders. We cheered the Finns on so in those days…the only country to pay its war debt! In Britain they were seriously thinking of sending aid to them, including men and materiel. This was the Bore War period. The war might have taken a very different direction had that happened. Instead the Finland-Soviet conflict ended badly for the Finns.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment